In the British town of Sidmouth in Devon, a dozen rare silent films have been discovered recently in a dumped shelf unit at a recycling centre. Film buffs Mike Grant and his daughter Rachel found the trove with films from France, Italy, India and the UK from circa 1909 to 1913. It included the MGM-comedy The Cardboard Lover (Robert Z. Leonard, 1928), of which only one other copy is known. The films will be donated to the BFI.

Here at EFSP, we love this kind of news, and to celebrate it this post is dedicated to the star of The Cardboard Lover, Marion Davies (1897-1961). The American actress starred in nearly four dozen films between 1917 and 1937, but her once glittering career was later overshadowed by Orson Welles' classic Citizen Kane (1941) which viciously portrayed her as a talentless and sad failure. This year's Il Cinema Ritrovato presented her film The Patsy (1928) at The Piazza Maggiore to an audience of thousands. This delicious, magnificent gem directed by King Vidor showed that Davies was one of the great comedic actresses of the silent era.

Promotion card for Il Cinema Ritrovato, Bologna, 2017. Photo: publicity still for The Patsy (King Vidor, 1928) with Marion Davies (middle), Jane Winton, Orville Caldwell, Marie Dressler and Dell Henderson.

Austrian postcard by Iris-Verlag, no. 578. Photo: Fanamet-Film.

Italian postcard by Casa Editrice Ballerini & Fratini, Firenze (B.F.F. Editore), no. 373. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn, Roma. Publicity still for The Red Mill (Roscoe 'Fatty' Arbuckle (as William Goodrich), 1927) with Owen Moore.

Marion Davies was born Marion Cecelia Douras in the borough of Brooklyn, New York in 1897. She had been bitten by the show biz bug early as she watched her sisters perform in local stage productions. She wanted to do the same. As Marion got older, she tried out for various school plays and did fairly well. Once her formal education had ended, Marion began her career as a chorus girl in New York City, first in the Pony Follies and eventually in the famous Ziegfeld Follies.

Her stage name came when she and her family passed the Davies Insurance Building. One of her sisters called out "Davies!!! That shall be my stage name," and the whole family took on that name. Marion wanted more than to dance. Acting, to her, was the epitome of show business and she aimed her sights in that direction. She had met newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst and went to live with him at his San Simeon castle in California. They would stay together for over 30 years, while Hearst’s wife Millicent resided in New York. Millicent would not grant him a divorce so that he could marry Davies.

San Simeon is a spectacular and elaborate mansion, which now stands as a California landmark. At San Simeon, the couple threw elaborate parties, frequented by all of the top names in Hollywood and other celebrities including the mayor of New York City, President Calvin Coolidge and Charles Lindbergh.

When she was 20, Marion made her first film, Runaway Romany (George W. Lederer, 1917). Written by Marion and directed by her brother-in-law, the film wasn't exactly a box-office smash, but for Marion, it was a start and a stepping stone to bigger things.

The following year Marion starred in The Burden of Proof (John G. Adolfi, Julius Steger, 1918) and Cecilia of the Pink Roses (Julius Steger, 1918). The latter film was backed by William Randolph Hearst. Because of Hearst's newspaper empire, Marion would be promoted as no actress before her. She appeared in numerous films over the next few years, including the superior comedy Getting Mary Married (Allan Dwan, 1919) with Norman Kerry, the suspenseful The Cinema Murder (George D. Baker, 1919) and the drama The Restless Sex (Leon D'Usseau, Robert Z. Leonard, 1920) with Carlyle Blackwell.

British postcard. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

British postcard. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

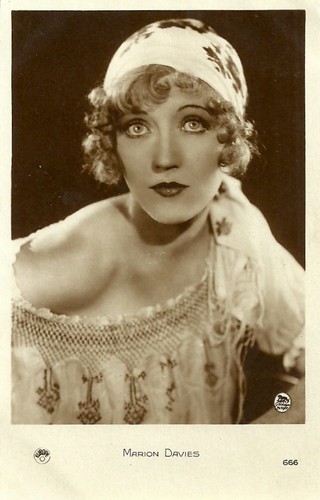

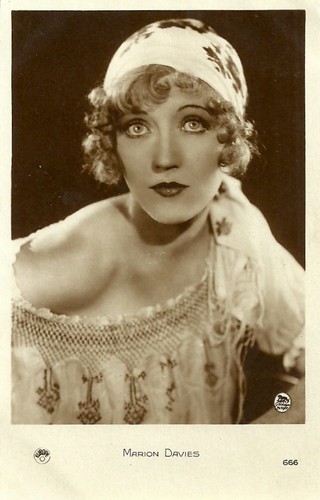

French postcard by Europe, no. 666. Photo: Goldwyn Mayer.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 3732/1, 1928-1929. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

In 1922, Marion Davies appeared as Mary Tudor in the historical romantic epic, When Knighthood Was in Flower (Robert G. Vignola, 1922). It was a film into which Hearst poured millions of dollars as a showcase for her. Although Marion didn't normally appear in period pieces, she turned in a wonderful performance, according to Denny Jackson at IMDb, and the film became a box office hit. Marion remained busy, one of the staples in cinemas around the country. Time after time, film after film, Marion turned in masterful performances. Her best films were the comedies The Patsy (1928) also with Marie Dressler, and Show People (1929) with William Haines, both directed by King Vidor.

At the end of the 1920s, it was obvious that sound films were about to replace the silent films. Marion was nervous because she had a stutter when she became excited and worried she wouldn't make a successful transition to the new medium. But she was a true professional who had no problem with the change. In 1930, two of her better films were Not So Dumb (King Vidor, 1930) and The Florodora Girl (Harry Beaumont, 1930), with Lawrence Grant. By the early 1930s, Marion had lost her box office appeal and the downward slide began. Hearst tried to push MGM executives to hire Marion for the role of Elizabeth Barrett in The Barretts of Wimpole Street (Sidney Franklin, 1934). Louis B. Mayer had other ideas and hired producer Irving Thalberg's wife Norma Shearer instead. Hearst reacted by pulling his newspaper support for MGM without much impact.

By the late 1930s, Hearst suffered financial reversals and Marion bailed him out by selling off $1 million of her jewellery. Hearst's financial problems also spelt the end of her career. Although she made the transition to sound, other stars fared better and her roles became fewer and further between. In 1937, a 40-year-old Marion filmed her last movie, Ever Since Eve (Lloyd Bacon, 1937) with Robert Montgomery. Out of films and with the intense pressures of her relationship with Hearst, Marion turned more and more to alcohol. Despite those problems, Marion was a very sharp and savvy businesswoman.

When Hearst lay dying in 1951 at age 88, Davies was given a sedative by his lawyer. When she awoke several hours later, she discovered that Hearst had passed away and that his associates had removed his body as well as all his belongings and any trace that he had lived there with her. His family had a big formal funeral for him in San Francisco, from which she was banned Later, Marion married for the first time at the age of 54, to Horace Brown. The union would last until she died of cancer in 1961 in Los Angeles, California. She was 64 years old. Upon Marion’s niece Patricia Van Cleve Lake's death, it was revealed she had been the love child of Davies and Hearst.

The love affair of Marion Davies and Hearst was mirrored in the films Citizen Kane (Orson Welles, 1941), RKO 281 (Benjamin Ross, 1999), and The Cat's Meow (Peter Bogdanovich, 2001). In Citizen Kane (1941), the title character's second wife (played by Dorothy Comingore) — an untalented singer whom he tries to promote — was widely assumed to be based on Davies. But many commentators, including Citizen Kane writer/director Orson Welles himself, have defended Davies' record as a gifted actress, to whom Hearst's patronage did more harm than good.

Italian postcard. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

French postcard by Europe, no. 1029. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

American postcard by C.T. & Co., Chi, in the series Homes of Movie Stars in California. Residence of Marion Davies, Beverly Hills

Sources: Nick Enoch (Mail on Line), Denny Jackson (IMDb), Wikipedia and IMDb.

This post was last updated on 1 December 2023.

Here at EFSP, we love this kind of news, and to celebrate it this post is dedicated to the star of The Cardboard Lover, Marion Davies (1897-1961). The American actress starred in nearly four dozen films between 1917 and 1937, but her once glittering career was later overshadowed by Orson Welles' classic Citizen Kane (1941) which viciously portrayed her as a talentless and sad failure. This year's Il Cinema Ritrovato presented her film The Patsy (1928) at The Piazza Maggiore to an audience of thousands. This delicious, magnificent gem directed by King Vidor showed that Davies was one of the great comedic actresses of the silent era.

Promotion card for Il Cinema Ritrovato, Bologna, 2017. Photo: publicity still for The Patsy (King Vidor, 1928) with Marion Davies (middle), Jane Winton, Orville Caldwell, Marie Dressler and Dell Henderson.

Austrian postcard by Iris-Verlag, no. 578. Photo: Fanamet-Film.

Italian postcard by Casa Editrice Ballerini & Fratini, Firenze (B.F.F. Editore), no. 373. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn, Roma. Publicity still for The Red Mill (Roscoe 'Fatty' Arbuckle (as William Goodrich), 1927) with Owen Moore.

The famous Ziegfeld Follies

Marion Davies was born Marion Cecelia Douras in the borough of Brooklyn, New York in 1897. She had been bitten by the show biz bug early as she watched her sisters perform in local stage productions. She wanted to do the same. As Marion got older, she tried out for various school plays and did fairly well. Once her formal education had ended, Marion began her career as a chorus girl in New York City, first in the Pony Follies and eventually in the famous Ziegfeld Follies.

Her stage name came when she and her family passed the Davies Insurance Building. One of her sisters called out "Davies!!! That shall be my stage name," and the whole family took on that name. Marion wanted more than to dance. Acting, to her, was the epitome of show business and she aimed her sights in that direction. She had met newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst and went to live with him at his San Simeon castle in California. They would stay together for over 30 years, while Hearst’s wife Millicent resided in New York. Millicent would not grant him a divorce so that he could marry Davies.

San Simeon is a spectacular and elaborate mansion, which now stands as a California landmark. At San Simeon, the couple threw elaborate parties, frequented by all of the top names in Hollywood and other celebrities including the mayor of New York City, President Calvin Coolidge and Charles Lindbergh.

When she was 20, Marion made her first film, Runaway Romany (George W. Lederer, 1917). Written by Marion and directed by her brother-in-law, the film wasn't exactly a box-office smash, but for Marion, it was a start and a stepping stone to bigger things.

The following year Marion starred in The Burden of Proof (John G. Adolfi, Julius Steger, 1918) and Cecilia of the Pink Roses (Julius Steger, 1918). The latter film was backed by William Randolph Hearst. Because of Hearst's newspaper empire, Marion would be promoted as no actress before her. She appeared in numerous films over the next few years, including the superior comedy Getting Mary Married (Allan Dwan, 1919) with Norman Kerry, the suspenseful The Cinema Murder (George D. Baker, 1919) and the drama The Restless Sex (Leon D'Usseau, Robert Z. Leonard, 1920) with Carlyle Blackwell.

British postcard. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

British postcard. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

French postcard by Europe, no. 666. Photo: Goldwyn Mayer.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 3732/1, 1928-1929. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

A very sharp and savvy businesswoman

In 1922, Marion Davies appeared as Mary Tudor in the historical romantic epic, When Knighthood Was in Flower (Robert G. Vignola, 1922). It was a film into which Hearst poured millions of dollars as a showcase for her. Although Marion didn't normally appear in period pieces, she turned in a wonderful performance, according to Denny Jackson at IMDb, and the film became a box office hit. Marion remained busy, one of the staples in cinemas around the country. Time after time, film after film, Marion turned in masterful performances. Her best films were the comedies The Patsy (1928) also with Marie Dressler, and Show People (1929) with William Haines, both directed by King Vidor.

At the end of the 1920s, it was obvious that sound films were about to replace the silent films. Marion was nervous because she had a stutter when she became excited and worried she wouldn't make a successful transition to the new medium. But she was a true professional who had no problem with the change. In 1930, two of her better films were Not So Dumb (King Vidor, 1930) and The Florodora Girl (Harry Beaumont, 1930), with Lawrence Grant. By the early 1930s, Marion had lost her box office appeal and the downward slide began. Hearst tried to push MGM executives to hire Marion for the role of Elizabeth Barrett in The Barretts of Wimpole Street (Sidney Franklin, 1934). Louis B. Mayer had other ideas and hired producer Irving Thalberg's wife Norma Shearer instead. Hearst reacted by pulling his newspaper support for MGM without much impact.

By the late 1930s, Hearst suffered financial reversals and Marion bailed him out by selling off $1 million of her jewellery. Hearst's financial problems also spelt the end of her career. Although she made the transition to sound, other stars fared better and her roles became fewer and further between. In 1937, a 40-year-old Marion filmed her last movie, Ever Since Eve (Lloyd Bacon, 1937) with Robert Montgomery. Out of films and with the intense pressures of her relationship with Hearst, Marion turned more and more to alcohol. Despite those problems, Marion was a very sharp and savvy businesswoman.

When Hearst lay dying in 1951 at age 88, Davies was given a sedative by his lawyer. When she awoke several hours later, she discovered that Hearst had passed away and that his associates had removed his body as well as all his belongings and any trace that he had lived there with her. His family had a big formal funeral for him in San Francisco, from which she was banned Later, Marion married for the first time at the age of 54, to Horace Brown. The union would last until she died of cancer in 1961 in Los Angeles, California. She was 64 years old. Upon Marion’s niece Patricia Van Cleve Lake's death, it was revealed she had been the love child of Davies and Hearst.

The love affair of Marion Davies and Hearst was mirrored in the films Citizen Kane (Orson Welles, 1941), RKO 281 (Benjamin Ross, 1999), and The Cat's Meow (Peter Bogdanovich, 2001). In Citizen Kane (1941), the title character's second wife (played by Dorothy Comingore) — an untalented singer whom he tries to promote — was widely assumed to be based on Davies. But many commentators, including Citizen Kane writer/director Orson Welles himself, have defended Davies' record as a gifted actress, to whom Hearst's patronage did more harm than good.

Italian postcard. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

French postcard by Europe, no. 1029. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

American postcard by C.T. & Co., Chi, in the series Homes of Movie Stars in California. Residence of Marion Davies, Beverly Hills

Sources: Nick Enoch (Mail on Line), Denny Jackson (IMDb), Wikipedia and IMDb.

This post was last updated on 1 December 2023.

No comments:

Post a Comment