Tonight, EFSP collaborator Ivo Blom will introduce the screening of Vittorio de Sica's classic Sciuscià/Shoeshine (1946) at Eye Filmmuseum in Amsterdam. Actor and director Vittorio De Sica (1901-1974) was a Maestro, a father, and a beacon of Italian cinema. De Sica was Italy's first modern superstar and EFSP salutes him.

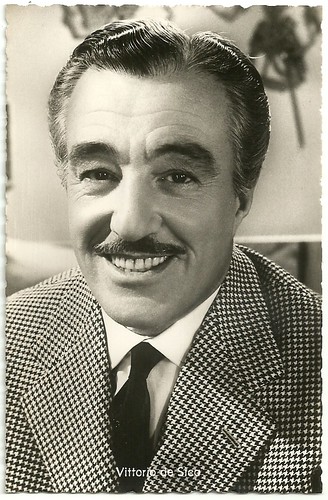

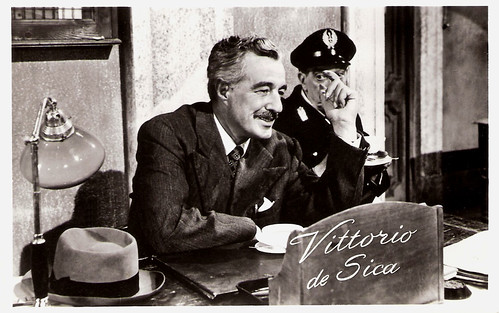

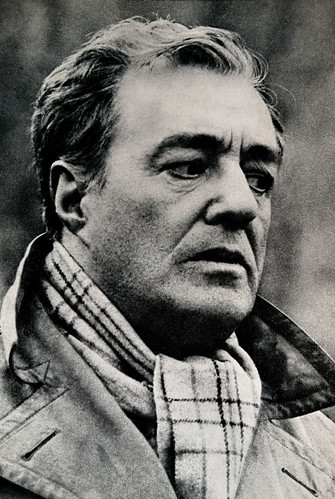

Italian postcard by Rizzoli S.C., Milano, 1936.

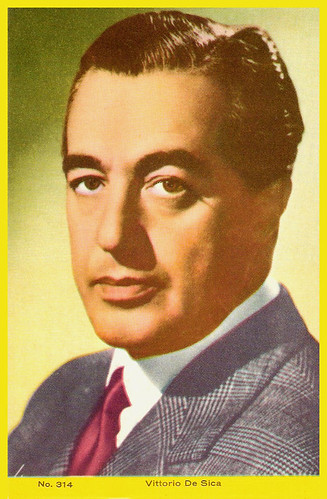

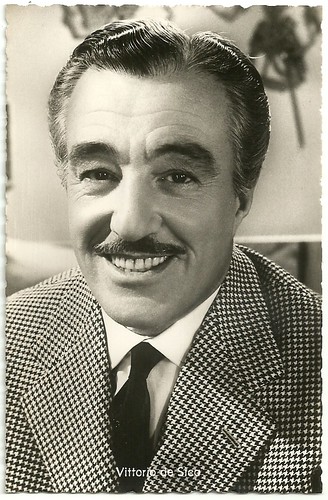

Mexican card, no. 314.

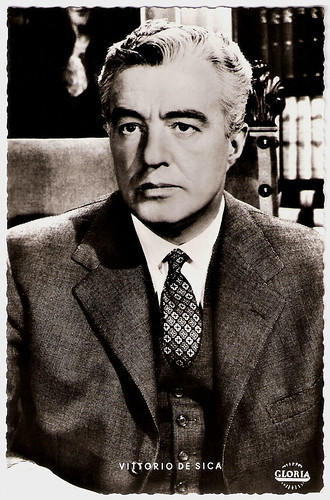

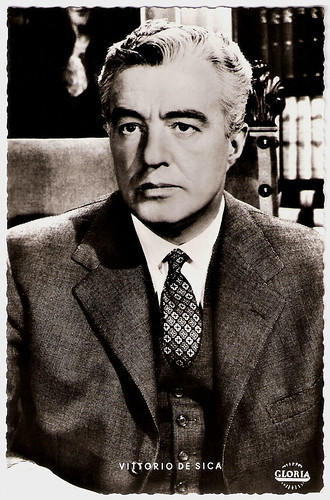

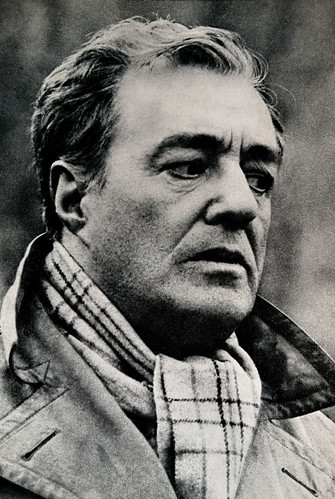

German postcard by Kunst und Bild, Berlin, no. V 377. Photo: Gloria Film. Publicity still for Racconti Romani/Roman Tales (Gianni Franciolini, 1955).

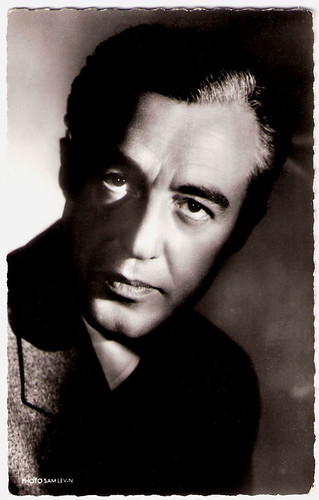

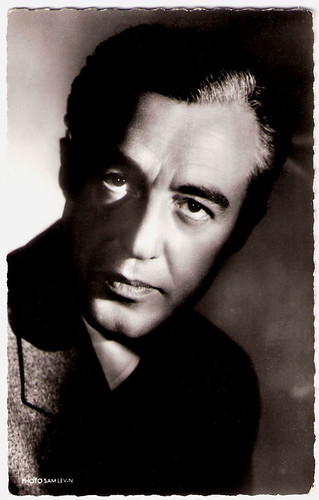

French postcard by Editions P.I., no. 37 G, presented by Les Carbones Korès Carboplane. Photo: Sam Lévin.

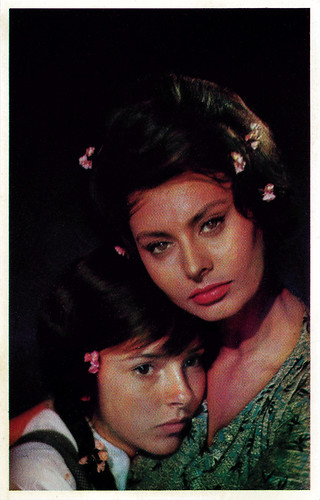

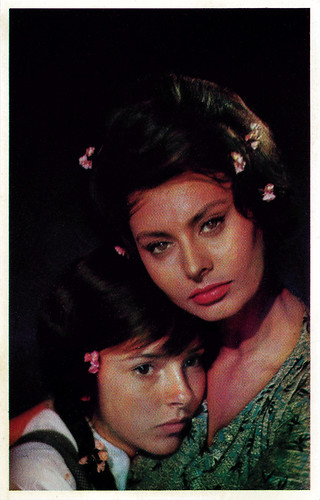

French postcard in the Collection Cinéma series by La Malibran, Paris, 1990, no. CI 13. Sophia Loren and Vittorio De Sica on the set of Boccaccio '70 (Vittorio De Sica, a.o., 1962).

Vittorio Domenico Stanislao Gaetano Sorano De Sica was born in Sora, Italy in 1901 (or 1902 - sources are divided). He grew up in Naples. His father, Umberto De Sica, a bank clerk with a penchant for show business, encouraged his good-looking son to pursue a stage career. Vittorio made his screen debut at 16 in the film Il processo Clémenceau/The Clemenceau Affair (Alfredo De Antoni, 1917) starring the legendary diva Francesca Bertini.

He began his career as a theatre actor in the early 1920s and joined Tatiana Pavlova's theatre company in 1923. By the late 1920s, he was a successful matinee idol of the Italian stage and also appeared in such silent films as La Bellezza del mondo/Beauty of the World (Mario Almirante, 1927) starring another silent film diva, Italia Almirante-Manzini.

In 1933 De Sica founded his own theatre company with his wife, actress Giuditta Rissone, and Sergio Tofano. The company performed mostly light comedies. His good looks and breezy manner made him an overnight matinee idol of the Italian cinema with the release of his first sound picture, La Vecchia Signora/The Old Lady (Amleto Palermi, 1932).

Light comedies as Gli uomini che mascalzoni!/What Scoundrels Men Are! (Mario Camerini, 1932) and Il Signor Max/Mister Max (Mario Camerini, 1937) made him immensely popular with female audiences. During the Second World War De Sica turned to directing with Rose Scarlatte/Red Roses (Vittorio De Sica, Giuseppe Amato, 1940), and Maddelena, Zero in Condotta/Maddelena, Zero For Conduct (Vittorio De Sica, 1940).

Both films were attempts to bring theatre pieces to the screen with suitable roles for himself. In the Comedy of Errors Teresa Venerdi (Vittorio De Sica, 1941) his girlfriend was played by a young Anna Magnani.

Spanish postcard by Amatller Marca Luna chocolate, Series 2a, no. 1. Photo: Caesar Film. A young Vittorio De Sica in Il processo Clémenceau (Alfredo De Antoni, 1917), starring Francesca Bertini. In Spain, the film was released as El proceso Clemenceau. In the film, this scene is mirrored. Young Pierre Clemenceau tells his mother he has won the first prize and may start working at the sculptor studio of the father of his friend Costantino.

Italian postcard by Edizioni artistiche Alberani. Portrait by Nanni. Alberani was a Bologna-based pharmaceutic company, which for decades made publicity for its 'sali di frutta'. Here Vittorio De Sica is clearly associated with the Jazz Age.

Spanish postcard by Editorial Brujuero, Barcelona, no. 481. Photo: Infonal, Archivo Bermeja.

Italian postcard. The caption reads: Elsa Merlini returns, all pepper. Probably for the film Non ti conosco più/I Don't Know You Anymore (Nunzio Malasomma, Mario Bonnard, 1936). The pepper refers to the title of her previous film Paprika (Carl Boese, 1933).

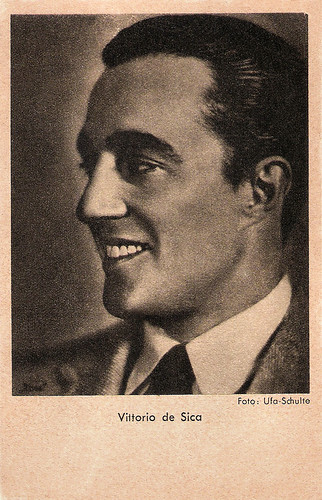

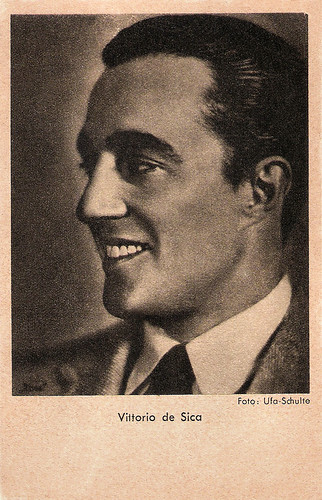

German postcard by Das Programm von Heute, Berlin. Photo: Ufa / Schulte.

A turning point in Vittorio De Sica’s career was his meeting with the writer Cesare Zavattini. They worked together on De Sica’s fifth film, I bambini ci guardano/The Children Are Watching Us (Vittorio De Sica, 1943). In this film, the director began to use non-professional actors and socially conscious subject matter. He revealed hitherto unsuspected depths and an extraordinarily sensitive touch with actors, especially with children.

I bambini ci guardano/The Children Are Watching Us is a mature, perceptive, and deeply human work about the impact of adult folly on a child's innocent mind. Zavattini became a scenarist and his major collaborator for the next three decades.

Together they created two of the most significant films of the Italian neorealism movement: Sciuscià/Shoeshine (Vittorio de Sica, 1946) and Ladri di biciclette/Bicycle Thieves (Vittorio de Sica, 1948). Sciuscià/Shoeshine is the story of how the lasting friendship of two homeless boys, who make their living shining shoes for the American G.I.'s, is betrayed by their contact with adults. At the end of the film, one boy inadvertently causes the other's death.

In Ladri di biciclette/Bicycle Thieves, workman Ricci's desperate search for his bicycle is an odyssey that enables us to witness a varied collection of characters and situations among the poor and working class of Rome. At Sony Pictures Classics, an anonymous critic writes: “With no money available to produce his films, De Sica initiated the use of real locations and non-professional actors. Using available light and documentary effects, he explored the relationship between working and lower-class characters in an indifferent, and often hostile social and political environment. The result was gritty and searing storytelling that not only bared the truth about the harsh conditions inflicted on Italy's poor but also represented a radical break from filmmaking conventions.” Both films are heartbreaking studies of poverty in postwar Italy and both won special Oscars before the foreign film category was officially established.

De Sica's next collaboration with Zavattini was the satirical fantasy, Miracolo a Milano/Miracle in Milan (Vittorio de Sica, 1951), which wavered between optimism and despair in its allegorical treatment of the plight of the poor in an industrial society. Umberto D. (Vittorio de Sica, 1952), was a relentlessly bleak study of the problems of old age and loneliness, but it was a box-office disaster. Continually wooed by Hollywood, De Sica finally acquiesced to make Stazioni Termini (Vittorio de Sica, 1952), clumsily renamed Indiscretion of an American Wife in the US. It was produced by David O. Selznick and filmed in Rome with Selznick's wife, Jennifer Jones and Montgomery Clift in the leading roles. Unfortunately, neorealist representation formed only an insignificant background to this typically American star vehicle.

Italian postcard by Aser, Roma (Rome), no. 333. Photo: Vaselli.

German postcard by Kolibri-Verlag, Minden. Photo: Bavaria Filmkunst-Eichberg-Marszalos. Publicity still for the Franco-Italian-German film Casino de Paris (André Hunebelle, 1957).

Dutch postcard by Takken, no. 1679.

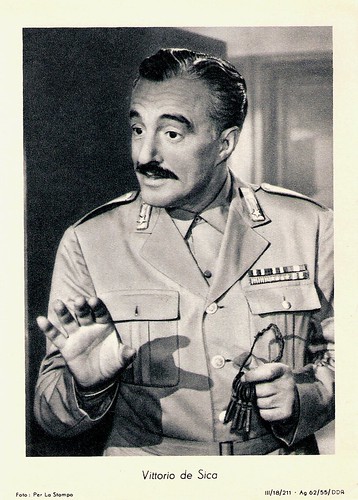

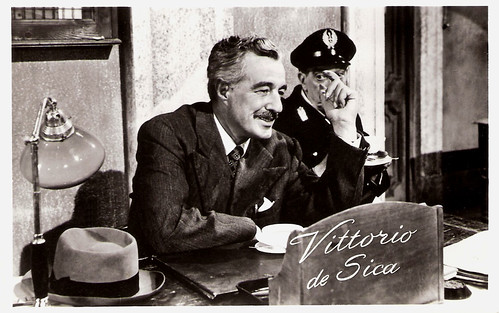

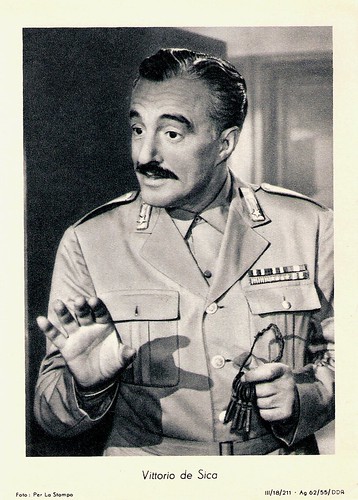

East-German postcard, no. III/18/211, 1955. Photo: Per la Stampa. De Sica wears the uniform of the marshall from the film Pane, amore e fantasia (and its sequels).

Belgian postcard by Ets. Dagneaux & Co. for STAR, Chewing-gum. Sophia Loren and Eleonora Brown in La ciociara/Two Women (Vittorio De Sica, 1960).

During his lifetime, Vittorio De Sica acted in over one hundred films in Italy and abroad, to finance his own directorial projects. He turned almost exclusively to acting in the late 1950s, enjoying great popularity in the role of the rural police officer Carotenuto in Pane, amore e fantasia/Bread, Love and Dreams (Luigi Comencini, 1954) opposite Gina Lollobrigida. He returned in a subsequent comedy series of the same name co-starring Lollobrigida or Sophia Loren.

He was at his best playing breezy comic heroes, men of great self-assurance or confidence - such as in Rossellini's General Della Rovere (Roberto Rossellini, 1959). On TV he became well known in the British Series The Four Just Men (1959) produced by Sapphire Films. With the notable exception of Il Tetto/The Roof (Vittorio de Sica, 1956) and La Ciociara/Two Women (Vittorio de Sica, 1960), for which Sophia Loren won an Oscar for Best Actress, his subsequent output as a director was for a long while markedly less inspired and significant.

He had two box-office hits with Matrimonio All'Italiana/Marriage Italian Style (Vittorio de Sica, 1964) starring Loren and Marcello Mastroianni, and with Ieri, oggi, domain/Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow (Vittorio de Sica, 1964) which won him another Oscar. However, critics and audiences alike had concluded that the ageing director had lost his touch, but, just before he died he made a dramatic comeback with Il giardino dei Finzi Contini/The Garden of the Finzi-Continis (Vittorio de Sica, 1970). The film was based on a Bassani novel about the incarceration of Italian Jews during the war.

According to Joel Kanoff at Film Reference, it shows “a strong Viscontian influence in its lavish setting and thematics (the film deals with the dissolution of the bourgeois family).” It won him yet another Oscar. The director's next film was Una breve vacanza/A Brief Vacation (Vittorio de Sica, 1973), about a working-class Italian woman's first taste of freedom in a society dominated by males. His last film, Il Viaggio/The Voyage (Vittorio de Sica, 1974), was based on a novella by Luigi Pirandello.

That year, he passed away following the removal of a cyst from his lungs. He had been married to Giuditta Rissone (1937-1968) and to Spanish actress María Mercader (1968-1974) with whom he had two sons, composer-director Manuel De Sica and actor-singer Christian De Sica. De Sica lived with Mercader from 1942 on, but couldn't marry her until 1968 after acquiring French citizenship, which allowed him to finally divorce Rissone. In 1974, Vittorio De Sica died near Paris in Neuilly-sur-Seine, at the age of 72. Active to the end, he appeared as himself in Scola's melancholic comedy-drama C'eravamo tanto amati/We All Loved Each Other So Much (Ettore Scola, 1974), which was released after his death.

French postcard by Editions du Globe, Paris, no. 610. Photo: Sam Lévin.

Romanian postcard by Casa Filmului Acin. Collection: Alina Deaconu.

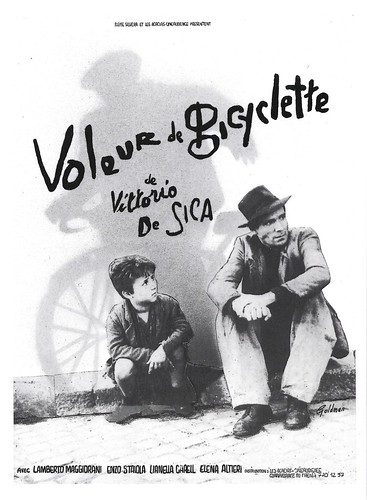

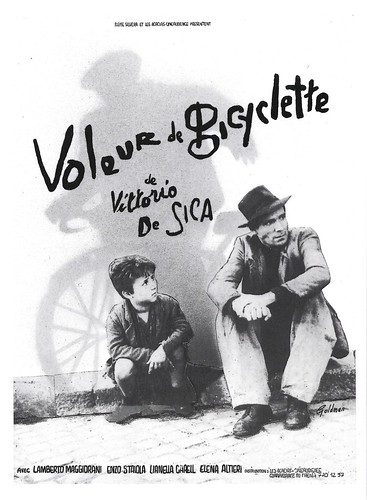

Postcard, reproduction of French poster based on a classic still from Ladri di biciclette/Bicycle Thieves (Vittorio De Sica, 1948), with Lamberto Maggiorani and Enzo Staiola.

Postcard, reproduction of Italian poster for Miracolo a Milano (Vittorio De Sica, 1951) by ENIC. Poster design: Ercole Brini.

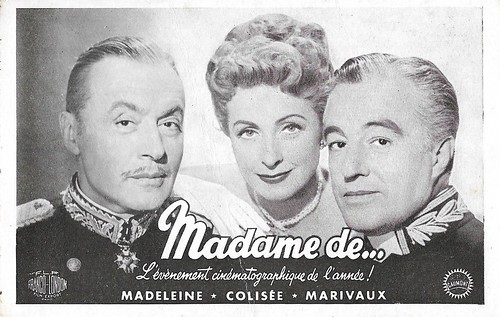

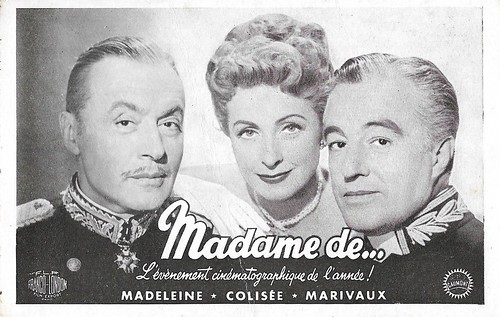

French postcard. Gaumont. F.L.F. Franco-London Film Export. Publicity for the film at the Parisian cinemas Madeleine, Colisée, and Marivaux. Charles Boyer, Danielle Darrieux, and Vittorio De Sica in Madame de... (Max Ophüls, 1953).

Scene from Miracolo a Milano/Miracle in Milan (1953). Source: Franco Maria Fontana (YouTube).

Sophia Loren and Vittorio De Sica dance the mambo in Pane, amore e.../Bread, Love and ... (1955). Source: Il Romanziere (YouTube).

Sources: Joel Kanoff (Film Reference), Dan Harper (Senses of Cinema), Michael Brooke (IMDb), TCM, Sony Pictures Classics, Wikipedia and IMDb.

Italian postcard by Rizzoli S.C., Milano, 1936.

Mexican card, no. 314.

German postcard by Kunst und Bild, Berlin, no. V 377. Photo: Gloria Film. Publicity still for Racconti Romani/Roman Tales (Gianni Franciolini, 1955).

French postcard by Editions P.I., no. 37 G, presented by Les Carbones Korès Carboplane. Photo: Sam Lévin.

French postcard in the Collection Cinéma series by La Malibran, Paris, 1990, no. CI 13. Sophia Loren and Vittorio De Sica on the set of Boccaccio '70 (Vittorio De Sica, a.o., 1962).

Successful matinee idol

Vittorio Domenico Stanislao Gaetano Sorano De Sica was born in Sora, Italy in 1901 (or 1902 - sources are divided). He grew up in Naples. His father, Umberto De Sica, a bank clerk with a penchant for show business, encouraged his good-looking son to pursue a stage career. Vittorio made his screen debut at 16 in the film Il processo Clémenceau/The Clemenceau Affair (Alfredo De Antoni, 1917) starring the legendary diva Francesca Bertini.

He began his career as a theatre actor in the early 1920s and joined Tatiana Pavlova's theatre company in 1923. By the late 1920s, he was a successful matinee idol of the Italian stage and also appeared in such silent films as La Bellezza del mondo/Beauty of the World (Mario Almirante, 1927) starring another silent film diva, Italia Almirante-Manzini.

In 1933 De Sica founded his own theatre company with his wife, actress Giuditta Rissone, and Sergio Tofano. The company performed mostly light comedies. His good looks and breezy manner made him an overnight matinee idol of the Italian cinema with the release of his first sound picture, La Vecchia Signora/The Old Lady (Amleto Palermi, 1932).

Light comedies as Gli uomini che mascalzoni!/What Scoundrels Men Are! (Mario Camerini, 1932) and Il Signor Max/Mister Max (Mario Camerini, 1937) made him immensely popular with female audiences. During the Second World War De Sica turned to directing with Rose Scarlatte/Red Roses (Vittorio De Sica, Giuseppe Amato, 1940), and Maddelena, Zero in Condotta/Maddelena, Zero For Conduct (Vittorio De Sica, 1940).

Both films were attempts to bring theatre pieces to the screen with suitable roles for himself. In the Comedy of Errors Teresa Venerdi (Vittorio De Sica, 1941) his girlfriend was played by a young Anna Magnani.

Spanish postcard by Amatller Marca Luna chocolate, Series 2a, no. 1. Photo: Caesar Film. A young Vittorio De Sica in Il processo Clémenceau (Alfredo De Antoni, 1917), starring Francesca Bertini. In Spain, the film was released as El proceso Clemenceau. In the film, this scene is mirrored. Young Pierre Clemenceau tells his mother he has won the first prize and may start working at the sculptor studio of the father of his friend Costantino.

Italian postcard by Edizioni artistiche Alberani. Portrait by Nanni. Alberani was a Bologna-based pharmaceutic company, which for decades made publicity for its 'sali di frutta'. Here Vittorio De Sica is clearly associated with the Jazz Age.

Spanish postcard by Editorial Brujuero, Barcelona, no. 481. Photo: Infonal, Archivo Bermeja.

Italian postcard. The caption reads: Elsa Merlini returns, all pepper. Probably for the film Non ti conosco più/I Don't Know You Anymore (Nunzio Malasomma, Mario Bonnard, 1936). The pepper refers to the title of her previous film Paprika (Carl Boese, 1933).

German postcard by Das Programm von Heute, Berlin. Photo: Ufa / Schulte.

Real locations and non-professional actors

A turning point in Vittorio De Sica’s career was his meeting with the writer Cesare Zavattini. They worked together on De Sica’s fifth film, I bambini ci guardano/The Children Are Watching Us (Vittorio De Sica, 1943). In this film, the director began to use non-professional actors and socially conscious subject matter. He revealed hitherto unsuspected depths and an extraordinarily sensitive touch with actors, especially with children.

I bambini ci guardano/The Children Are Watching Us is a mature, perceptive, and deeply human work about the impact of adult folly on a child's innocent mind. Zavattini became a scenarist and his major collaborator for the next three decades.

Together they created two of the most significant films of the Italian neorealism movement: Sciuscià/Shoeshine (Vittorio de Sica, 1946) and Ladri di biciclette/Bicycle Thieves (Vittorio de Sica, 1948). Sciuscià/Shoeshine is the story of how the lasting friendship of two homeless boys, who make their living shining shoes for the American G.I.'s, is betrayed by their contact with adults. At the end of the film, one boy inadvertently causes the other's death.

In Ladri di biciclette/Bicycle Thieves, workman Ricci's desperate search for his bicycle is an odyssey that enables us to witness a varied collection of characters and situations among the poor and working class of Rome. At Sony Pictures Classics, an anonymous critic writes: “With no money available to produce his films, De Sica initiated the use of real locations and non-professional actors. Using available light and documentary effects, he explored the relationship between working and lower-class characters in an indifferent, and often hostile social and political environment. The result was gritty and searing storytelling that not only bared the truth about the harsh conditions inflicted on Italy's poor but also represented a radical break from filmmaking conventions.” Both films are heartbreaking studies of poverty in postwar Italy and both won special Oscars before the foreign film category was officially established.

De Sica's next collaboration with Zavattini was the satirical fantasy, Miracolo a Milano/Miracle in Milan (Vittorio de Sica, 1951), which wavered between optimism and despair in its allegorical treatment of the plight of the poor in an industrial society. Umberto D. (Vittorio de Sica, 1952), was a relentlessly bleak study of the problems of old age and loneliness, but it was a box-office disaster. Continually wooed by Hollywood, De Sica finally acquiesced to make Stazioni Termini (Vittorio de Sica, 1952), clumsily renamed Indiscretion of an American Wife in the US. It was produced by David O. Selznick and filmed in Rome with Selznick's wife, Jennifer Jones and Montgomery Clift in the leading roles. Unfortunately, neorealist representation formed only an insignificant background to this typically American star vehicle.

Italian postcard by Aser, Roma (Rome), no. 333. Photo: Vaselli.

German postcard by Kolibri-Verlag, Minden. Photo: Bavaria Filmkunst-Eichberg-Marszalos. Publicity still for the Franco-Italian-German film Casino de Paris (André Hunebelle, 1957).

Dutch postcard by Takken, no. 1679.

East-German postcard, no. III/18/211, 1955. Photo: Per la Stampa. De Sica wears the uniform of the marshall from the film Pane, amore e fantasia (and its sequels).

Belgian postcard by Ets. Dagneaux & Co. for STAR, Chewing-gum. Sophia Loren and Eleonora Brown in La ciociara/Two Women (Vittorio De Sica, 1960).

Bread love and dreams

During his lifetime, Vittorio De Sica acted in over one hundred films in Italy and abroad, to finance his own directorial projects. He turned almost exclusively to acting in the late 1950s, enjoying great popularity in the role of the rural police officer Carotenuto in Pane, amore e fantasia/Bread, Love and Dreams (Luigi Comencini, 1954) opposite Gina Lollobrigida. He returned in a subsequent comedy series of the same name co-starring Lollobrigida or Sophia Loren.

He was at his best playing breezy comic heroes, men of great self-assurance or confidence - such as in Rossellini's General Della Rovere (Roberto Rossellini, 1959). On TV he became well known in the British Series The Four Just Men (1959) produced by Sapphire Films. With the notable exception of Il Tetto/The Roof (Vittorio de Sica, 1956) and La Ciociara/Two Women (Vittorio de Sica, 1960), for which Sophia Loren won an Oscar for Best Actress, his subsequent output as a director was for a long while markedly less inspired and significant.

He had two box-office hits with Matrimonio All'Italiana/Marriage Italian Style (Vittorio de Sica, 1964) starring Loren and Marcello Mastroianni, and with Ieri, oggi, domain/Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow (Vittorio de Sica, 1964) which won him another Oscar. However, critics and audiences alike had concluded that the ageing director had lost his touch, but, just before he died he made a dramatic comeback with Il giardino dei Finzi Contini/The Garden of the Finzi-Continis (Vittorio de Sica, 1970). The film was based on a Bassani novel about the incarceration of Italian Jews during the war.

According to Joel Kanoff at Film Reference, it shows “a strong Viscontian influence in its lavish setting and thematics (the film deals with the dissolution of the bourgeois family).” It won him yet another Oscar. The director's next film was Una breve vacanza/A Brief Vacation (Vittorio de Sica, 1973), about a working-class Italian woman's first taste of freedom in a society dominated by males. His last film, Il Viaggio/The Voyage (Vittorio de Sica, 1974), was based on a novella by Luigi Pirandello.

That year, he passed away following the removal of a cyst from his lungs. He had been married to Giuditta Rissone (1937-1968) and to Spanish actress María Mercader (1968-1974) with whom he had two sons, composer-director Manuel De Sica and actor-singer Christian De Sica. De Sica lived with Mercader from 1942 on, but couldn't marry her until 1968 after acquiring French citizenship, which allowed him to finally divorce Rissone. In 1974, Vittorio De Sica died near Paris in Neuilly-sur-Seine, at the age of 72. Active to the end, he appeared as himself in Scola's melancholic comedy-drama C'eravamo tanto amati/We All Loved Each Other So Much (Ettore Scola, 1974), which was released after his death.

French postcard by Editions du Globe, Paris, no. 610. Photo: Sam Lévin.

Romanian postcard by Casa Filmului Acin. Collection: Alina Deaconu.

Postcard, reproduction of French poster based on a classic still from Ladri di biciclette/Bicycle Thieves (Vittorio De Sica, 1948), with Lamberto Maggiorani and Enzo Staiola.

Postcard, reproduction of Italian poster for Miracolo a Milano (Vittorio De Sica, 1951) by ENIC. Poster design: Ercole Brini.

French postcard. Gaumont. F.L.F. Franco-London Film Export. Publicity for the film at the Parisian cinemas Madeleine, Colisée, and Marivaux. Charles Boyer, Danielle Darrieux, and Vittorio De Sica in Madame de... (Max Ophüls, 1953).

Scene from Miracolo a Milano/Miracle in Milan (1953). Source: Franco Maria Fontana (YouTube).

Sophia Loren and Vittorio De Sica dance the mambo in Pane, amore e.../Bread, Love and ... (1955). Source: Il Romanziere (YouTube).

Sources: Joel Kanoff (Film Reference), Dan Harper (Senses of Cinema), Michael Brooke (IMDb), TCM, Sony Pictures Classics, Wikipedia and IMDb.

Thank you Bob for this recap of an amazing career.

ReplyDelete