Glamorous, seductive film star and engineer Hedy Lamarr (1913–2000) was born in Austria. The notorious Czechoslovak film Ekstase/Ecstasy (1933) made her an international sensation, and Louis B. Mayer invited her to Hollywood where she became ‘the most beautiful woman in films’. She also co-invented an early technique for spread spectrum communications, a key to many forms of wireless communication.

British postcard in the Picturegoer series, London, no. W 200. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM).

British postcard in the Picturegoer Series, London, no. W 976. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

British postcard in the Picturegoer Series, London, no. 1208a. Photo: Metro Goldwyn Mayer.

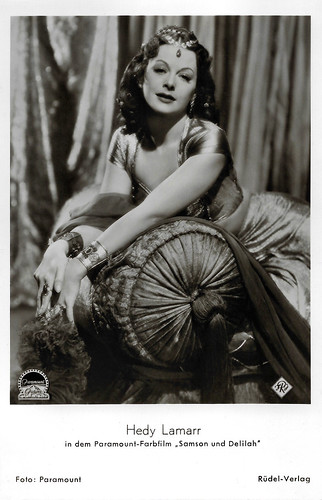

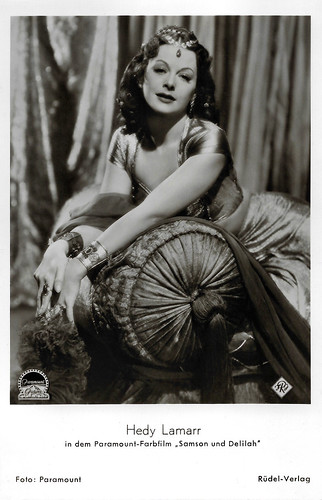

West-German postcard by Rüdel-Verlag, Hamburg-Bergedorf, no. 319. Photo: Paramount. Hedy Lamarr in Samson and Delilah (Cecil B. DeMille, 1949).

West-German postcard by Kolibri-Verlag, no. 1014. Photo: Paramount Pictures. Hedy Lamarr in My Favorite Spy (Norman Z. McLeod, 1951).

Hedy Lamarr was born as Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler in Vienna, Austria-Hungary (now Austria), in 1913. She was Jewish. Her mother, Gertrud Lichtwitz, was a pianist, and her father, Emil Kiesler, a successful bank director. She studied ballet and piano. She had very dark hair, her eyes were "pools where weak men drowned", and her breasts were apparently in order when she was just 18, auditioning for Max Reinhardt in Berlin. He called her the ‘most beautiful woman in Europe’. Yet he failed to detect enough evidence of an actor's energy or need, and so, Hedwig drifted into pictures.

Her first film role had been a bit part in the German film Das Geld liegt auf der Straße/Money on the Street (Georg Jacoby, 1930). Soon, the attractive teenager played major roles alongside stars like Heinz Rühmann and Hans Moser in the German films Die Frau von Lindenau/Storm in a Water Glass (Georg Jacoby, 1931), Die Abenteuer des Herrn O. F./The Trunks of Mr. O. F. (Alexis Granowsky, 1931), and Man braucht kein Geld/We Don't Need Money (Carl Boese, 1932).

But it would be her fifth film that catapulted her to worldwide fame. In early 1933, she starred in Gustav Machatý's Ekstase/Symphonie der Liebe/Ecstasy (1933), a Czechoslovak film made in Prague. It's the story of a young girl who has an indifferent old husband and falls in love with a young soldier. Close-ups of her face in orgasm, and long shots of her running nude through the woods, created a sensation all over the world. The Pope denounced the film. The scenes, tame by today's standards, caused the film to be banned by the US government.

Shortly before the film's release, Hedwig married Viennese millionaire, Fritz Mandl, a munitions manufacturer, 13 years her senior, and eager to have a trophy wife. Her new husband bought up as many copies of Ekstase as he could possibly find, as he objected to her nudity and ‘the expression on her face’. (She later claimed the looks of passion were the result of the director poking her in the bottom with a safety pin.) Mandl prevented her from pursuing her acting career and instead took her to meetings with technicians and business partners. In these meetings, the mathematically talented Lamarr learned about military technology. Otherwise, she had to stay home at castle Schwarzenau.

Hedy later related in her autobiography 'Ecstasy and Me' that even though Mandl was part-Jewish, he was consorting with Nazi industrialists which infuriated her, and dictators Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler both attended Mandl's grand parties.

American postcard. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

American postcard.

American postcard by EKC. Photo: W.T. Gray, Los Angeles.

French postcard by Editions Chantal, no. 10. Photo: MGM / Laszlo Willinger, 1939.

Dutch postcard by M. B. & Z. (M. Bonnist & Zonen, Amsterdam), no. 1059. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

In 1937, Hedy Kiesler was finally successful in escaping when she hired a new maid who resembled her. She convinced Mandl to allow her to attend a party wearing all her expensive jewelry. She drugged the maid and used her uniform as a disguise to escape out of the country. First, she fled to Paris, where she obtained a divorce, and then she moved on to London.

At Claridge's hotel, she encountered Louis B. Mayer, the mogul of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, who hired her. At his insistence, Hedwig changed her name to Hedy Lamarr. She chose the surname in homage to beautiful silent film star Barbara LaMarr, who had died from a drug overdose in 1926.

Her American debut was as the love interest of Charles Boyer in Algiers (John Cromwell, 1938), the re-make of the very successful French film, Pépé le Moko (Julien Duvivier, 1937). In Hollywood, Hedy was usually cast as elegant and mysterious. Between 1940 and 1949 she made 18 films, even though she had two children during that time: Denise Loder (1945) and Anthony Loder (1947).

Her MGM films include Boom Town (Jack Conway, 1940) with Clark Gable, the musical extravaganza Ziegfeld Girl (Robert Z. Leonard, 1941) with James Stewart, and opposite John Garfield in Tortilla Flat (Victor Fleming, 1942), based on the novel by John Steinbeck.

White Cargo (Richard Thorpe, 1942) was one of Lamarr's biggest hits at MGM. She appeared as the native girl Tondelayo, who seduces most of the men at a British trading post in Africa. The film contains arguably her most famous film quote, "I am Tondelayo".

Belgian collector's card by Kwatta, Series C, no. 106. Photo: MGM. Publicity still for Comrade X (King Vidor, 1940).

Belgian collector's card by Kwatta, Series C, no. 166. Photo: MGM. Publicity still for Comrade X (King Vidor, 1940) with Clark Gable.

Belgian collector's card by Kwatta, Series C, no. 166. Photo: MGM. Publicity still for Tortilla Flat (Victor Fleming, 1942) with John Garfield.

Belgian collector's card by Kwatta, Series C, no. 154 Photo: MGM. Publicity still for Tortilla Flat (Victor Fleming, 1942) with John Garfield.

Jan Christopher Horak described her star persona in a 2002 article in CineAction: "Lamarr consistently played strong, independent women who knew what their value was in the marketplace of erotic exchange, and were not afraid to bargain. Seldom did she go down on her knees before a man without already having an eye on the prize, rarely did she put her own desire behind that of a male partner. Lamarr broke taboos (on the screen and in the gossip columns) and many women in the audience had their secret pleasure watching her, while the boys gawked."

She was having nearly as many husbands as movies a year. In 1939-1940, she was married for 14 months to producer Gene Markey; there were affairs with Burgess Meredith and Reginald Gardiner, and a brief engagement to actor George Montgomery before she married another actor, Englishman John Loder - it lasted only four years.

In June 1941, Hedy Lamarr submitted the idea of a secret communication system, together with her neighbour and lover, noted modernist composer George Antheil (he did the music for the classic avant-garde film Ballet Mécanique (Fernand Leger, 1924)). On 11 August 1942, U.S. Patent 2,292,387 was granted to Antheil and 'Hedy Kiesler Markey', her married name at the time. This early version of frequency hopping used a piano roll to change between 88 frequencies.

The original idea, meant to solve the problem of enemies blocking signals from radio-controlled missiles during World War II, involved changing radio frequencies simultaneously to prevent enemies from being able to detect the messages. The idea was ahead of its time, and not feasible owing to the state of mechanical technology in 1942. It was not implemented in the USA until 1962 when it was used by US military ships during a blockade of Cuba after the patent had expired.

British postcard in the Colourgraph Series, London, no. C 380. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

British postcard in the Picturegoer Series, London, no. 1208. Photo: Walter Wanger.

Dutch postcard. Photo: R.K.O. Radio Films.

Dutch postcard. Photo: United Artists.

Hedy Lamarr left MGM in 1945. For Paramount she starred as Delilah opposite Victor Mature's Samson in Cecil B. DeMille's epic Samson and Delilah (1949). This proved to be Paramount's most profitable movie to date, bringing in $12 million in rental from theatres.

However, following her comedic turn opposite Bob Hope in My Favorite Spy (Norman Z. MacLeod, 1951), her career went into decline. She was to make only six more films between 1949 and 1957, the last being The Female Animal (Harry Keller, 1958). In 1953 she had become a naturalized US citizen.

In 1965 she was accused of shoplifting, and a year later followed Andy Warhol's short film Hedy/The Shoplifter (1966). The controversy surrounding the shoplifting charges coincided with an aborted return to the screen in Picture Mommy Dead (Bert I. Gordon, 1966). The role was ultimately filled by Zsa Zsa Gabor.

She wrote about it in her so-called memoirs 'Ecstasy and Me' (1967). She later sued the publisher claiming that many of the anecdotes in the book, which was described by a judge as "filthy, nauseating, and revolting", were fabricated by its ghostwriters, Leo Guild and Sy Rice.

Dutch postcard, no. 3114. Photo: MGM. Hedy Lamarr, Judy Garland, and Lana Turner in Ziegfeld Girl (Robert Z. Leonard, Busby Berkeley, 1941).

Dutch postcard by Foto Archief Film en Toneel, no. 3537. Photo: Metro Goldwyn Mayer.

Dutch postcard by J. Sleding N.V., Amsterdam, no. S 63. Photo: MGM.

French postcard by Editions P.I., Paris, no. 359. Photo: Paramount, 1953. Hedy Lamarr in Samson and Delilah (Cecil B. DeMille, 1949).

French postcard by Editions P.I, no. 24D, presented by Les Carbones Korès. Photo: Paramount, 1953.

In the ensuing years, she retreated from public life and settled in Florida. There were three more husbands: Teddy Stauffer, a bandleader who had worked in Acapulco; Howard Lee, a Texas oilman (he married Gene Tierney after Hedy); and a lawyer named Lewis Boles. All her marriages ended in divorce.

In 1991, she returned to the headlines when the 78-year-old former actress was arrested a couple of times on minor shoplifting charges (cosmetics and clothes), but the charges were settled.

In 2000, she was eventually found dead in a small home in Altamonte Springs, Florida, where she lived alone. She was 86, and she had experimented disastrously with plastic surgery. Her son Anthony Loder took her ashes to Vienna and spread them in the Wienerwald, according to her wishes.

Today, Lamarr's and Antheil's frequency-hopping idea serves as a basis for modern spread-spectrum communication technology, such as COFDM used in Wi-Fi network connections and CDMA used in some cordless and wireless telephones. For her contribution to the motion picture industry, Hedy Lamarr has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 6247 Hollywood Blvd.

Italian postcard by C.C.M., no. 11, distributed in Belgium by Victoria, Bruxelles. Photo: RKO Radio Films.

Italian postcard by Bromofoto, Milano, no. 222.

West-German postcard by Starfoto Hasemann, no. 225. Photo: Paramount Pictures.

West-German postcard by Kunst und Bild, Berlin, no. A 300. Photo: Paramount-Film.

British postcard in 'The People' series by Show Parade Picture Service, London, no. P 1127. Photo: Paramount. Hedy Lamarr in Copper Ranyon (John Farrow, 1950).

West-German postcard by H.S.K.-Verlag, Köln (Cologne), no. 501. Photo: Paramount. Ray Milland and Hedy Lamarr in Copper Canyon (John Farrow, 1950).

American postcard by Longshaw Card Co., Los Angeles, Calif, no. 821. Photo: John Hughes. Caption: Home of Hedy Lamarr.

West-German postcard in the 161 Andy Warhol series by Gebr. König Postkartenverlag, Köln, no. 161/4 (4 of 10), 1989. Illustration: Andy Warhol. Caption: Hedy Lamarr, 1962.

Sources: Jan Christopher Horak (CineAction), David Thomson (The Independent), HedyLamarr.com, Wikipedia, and IMDb.

This post was last updated on 25 June 2021.

British postcard in the Picturegoer series, London, no. W 200. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM).

British postcard in the Picturegoer Series, London, no. W 976. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

British postcard in the Picturegoer Series, London, no. 1208a. Photo: Metro Goldwyn Mayer.

West-German postcard by Rüdel-Verlag, Hamburg-Bergedorf, no. 319. Photo: Paramount. Hedy Lamarr in Samson and Delilah (Cecil B. DeMille, 1949).

West-German postcard by Kolibri-Verlag, no. 1014. Photo: Paramount Pictures. Hedy Lamarr in My Favorite Spy (Norman Z. McLeod, 1951).

Hedwig Kiesler

Hedy Lamarr was born as Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler in Vienna, Austria-Hungary (now Austria), in 1913. She was Jewish. Her mother, Gertrud Lichtwitz, was a pianist, and her father, Emil Kiesler, a successful bank director. She studied ballet and piano. She had very dark hair, her eyes were "pools where weak men drowned", and her breasts were apparently in order when she was just 18, auditioning for Max Reinhardt in Berlin. He called her the ‘most beautiful woman in Europe’. Yet he failed to detect enough evidence of an actor's energy or need, and so, Hedwig drifted into pictures.

Her first film role had been a bit part in the German film Das Geld liegt auf der Straße/Money on the Street (Georg Jacoby, 1930). Soon, the attractive teenager played major roles alongside stars like Heinz Rühmann and Hans Moser in the German films Die Frau von Lindenau/Storm in a Water Glass (Georg Jacoby, 1931), Die Abenteuer des Herrn O. F./The Trunks of Mr. O. F. (Alexis Granowsky, 1931), and Man braucht kein Geld/We Don't Need Money (Carl Boese, 1932).

But it would be her fifth film that catapulted her to worldwide fame. In early 1933, she starred in Gustav Machatý's Ekstase/Symphonie der Liebe/Ecstasy (1933), a Czechoslovak film made in Prague. It's the story of a young girl who has an indifferent old husband and falls in love with a young soldier. Close-ups of her face in orgasm, and long shots of her running nude through the woods, created a sensation all over the world. The Pope denounced the film. The scenes, tame by today's standards, caused the film to be banned by the US government.

Shortly before the film's release, Hedwig married Viennese millionaire, Fritz Mandl, a munitions manufacturer, 13 years her senior, and eager to have a trophy wife. Her new husband bought up as many copies of Ekstase as he could possibly find, as he objected to her nudity and ‘the expression on her face’. (She later claimed the looks of passion were the result of the director poking her in the bottom with a safety pin.) Mandl prevented her from pursuing her acting career and instead took her to meetings with technicians and business partners. In these meetings, the mathematically talented Lamarr learned about military technology. Otherwise, she had to stay home at castle Schwarzenau.

Hedy later related in her autobiography 'Ecstasy and Me' that even though Mandl was part-Jewish, he was consorting with Nazi industrialists which infuriated her, and dictators Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler both attended Mandl's grand parties.

American postcard. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

American postcard.

American postcard by EKC. Photo: W.T. Gray, Los Angeles.

French postcard by Editions Chantal, no. 10. Photo: MGM / Laszlo Willinger, 1939.

Dutch postcard by M. B. & Z. (M. Bonnist & Zonen, Amsterdam), no. 1059. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

Mathematics Talent

In 1937, Hedy Kiesler was finally successful in escaping when she hired a new maid who resembled her. She convinced Mandl to allow her to attend a party wearing all her expensive jewelry. She drugged the maid and used her uniform as a disguise to escape out of the country. First, she fled to Paris, where she obtained a divorce, and then she moved on to London.

At Claridge's hotel, she encountered Louis B. Mayer, the mogul of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, who hired her. At his insistence, Hedwig changed her name to Hedy Lamarr. She chose the surname in homage to beautiful silent film star Barbara LaMarr, who had died from a drug overdose in 1926.

Her American debut was as the love interest of Charles Boyer in Algiers (John Cromwell, 1938), the re-make of the very successful French film, Pépé le Moko (Julien Duvivier, 1937). In Hollywood, Hedy was usually cast as elegant and mysterious. Between 1940 and 1949 she made 18 films, even though she had two children during that time: Denise Loder (1945) and Anthony Loder (1947).

Her MGM films include Boom Town (Jack Conway, 1940) with Clark Gable, the musical extravaganza Ziegfeld Girl (Robert Z. Leonard, 1941) with James Stewart, and opposite John Garfield in Tortilla Flat (Victor Fleming, 1942), based on the novel by John Steinbeck.

White Cargo (Richard Thorpe, 1942) was one of Lamarr's biggest hits at MGM. She appeared as the native girl Tondelayo, who seduces most of the men at a British trading post in Africa. The film contains arguably her most famous film quote, "I am Tondelayo".

Belgian collector's card by Kwatta, Series C, no. 106. Photo: MGM. Publicity still for Comrade X (King Vidor, 1940).

Belgian collector's card by Kwatta, Series C, no. 166. Photo: MGM. Publicity still for Comrade X (King Vidor, 1940) with Clark Gable.

Belgian collector's card by Kwatta, Series C, no. 166. Photo: MGM. Publicity still for Tortilla Flat (Victor Fleming, 1942) with John Garfield.

Belgian collector's card by Kwatta, Series C, no. 154 Photo: MGM. Publicity still for Tortilla Flat (Victor Fleming, 1942) with John Garfield.

Strong and Independent

Jan Christopher Horak described her star persona in a 2002 article in CineAction: "Lamarr consistently played strong, independent women who knew what their value was in the marketplace of erotic exchange, and were not afraid to bargain. Seldom did she go down on her knees before a man without already having an eye on the prize, rarely did she put her own desire behind that of a male partner. Lamarr broke taboos (on the screen and in the gossip columns) and many women in the audience had their secret pleasure watching her, while the boys gawked."

She was having nearly as many husbands as movies a year. In 1939-1940, she was married for 14 months to producer Gene Markey; there were affairs with Burgess Meredith and Reginald Gardiner, and a brief engagement to actor George Montgomery before she married another actor, Englishman John Loder - it lasted only four years.

In June 1941, Hedy Lamarr submitted the idea of a secret communication system, together with her neighbour and lover, noted modernist composer George Antheil (he did the music for the classic avant-garde film Ballet Mécanique (Fernand Leger, 1924)). On 11 August 1942, U.S. Patent 2,292,387 was granted to Antheil and 'Hedy Kiesler Markey', her married name at the time. This early version of frequency hopping used a piano roll to change between 88 frequencies.

The original idea, meant to solve the problem of enemies blocking signals from radio-controlled missiles during World War II, involved changing radio frequencies simultaneously to prevent enemies from being able to detect the messages. The idea was ahead of its time, and not feasible owing to the state of mechanical technology in 1942. It was not implemented in the USA until 1962 when it was used by US military ships during a blockade of Cuba after the patent had expired.

British postcard in the Colourgraph Series, London, no. C 380. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

British postcard in the Picturegoer Series, London, no. 1208. Photo: Walter Wanger.

Dutch postcard. Photo: R.K.O. Radio Films.

Dutch postcard. Photo: United Artists.

The Shoplifter

Hedy Lamarr left MGM in 1945. For Paramount she starred as Delilah opposite Victor Mature's Samson in Cecil B. DeMille's epic Samson and Delilah (1949). This proved to be Paramount's most profitable movie to date, bringing in $12 million in rental from theatres.

However, following her comedic turn opposite Bob Hope in My Favorite Spy (Norman Z. MacLeod, 1951), her career went into decline. She was to make only six more films between 1949 and 1957, the last being The Female Animal (Harry Keller, 1958). In 1953 she had become a naturalized US citizen.

In 1965 she was accused of shoplifting, and a year later followed Andy Warhol's short film Hedy/The Shoplifter (1966). The controversy surrounding the shoplifting charges coincided with an aborted return to the screen in Picture Mommy Dead (Bert I. Gordon, 1966). The role was ultimately filled by Zsa Zsa Gabor.

She wrote about it in her so-called memoirs 'Ecstasy and Me' (1967). She later sued the publisher claiming that many of the anecdotes in the book, which was described by a judge as "filthy, nauseating, and revolting", were fabricated by its ghostwriters, Leo Guild and Sy Rice.

Dutch postcard, no. 3114. Photo: MGM. Hedy Lamarr, Judy Garland, and Lana Turner in Ziegfeld Girl (Robert Z. Leonard, Busby Berkeley, 1941).

Dutch postcard by Foto Archief Film en Toneel, no. 3537. Photo: Metro Goldwyn Mayer.

Dutch postcard by J. Sleding N.V., Amsterdam, no. S 63. Photo: MGM.

French postcard by Editions P.I., Paris, no. 359. Photo: Paramount, 1953. Hedy Lamarr in Samson and Delilah (Cecil B. DeMille, 1949).

French postcard by Editions P.I, no. 24D, presented by Les Carbones Korès. Photo: Paramount, 1953.

Disastrous Plastic Surgery Experiments

In the ensuing years, she retreated from public life and settled in Florida. There were three more husbands: Teddy Stauffer, a bandleader who had worked in Acapulco; Howard Lee, a Texas oilman (he married Gene Tierney after Hedy); and a lawyer named Lewis Boles. All her marriages ended in divorce.

In 1991, she returned to the headlines when the 78-year-old former actress was arrested a couple of times on minor shoplifting charges (cosmetics and clothes), but the charges were settled.

In 2000, she was eventually found dead in a small home in Altamonte Springs, Florida, where she lived alone. She was 86, and she had experimented disastrously with plastic surgery. Her son Anthony Loder took her ashes to Vienna and spread them in the Wienerwald, according to her wishes.

Today, Lamarr's and Antheil's frequency-hopping idea serves as a basis for modern spread-spectrum communication technology, such as COFDM used in Wi-Fi network connections and CDMA used in some cordless and wireless telephones. For her contribution to the motion picture industry, Hedy Lamarr has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 6247 Hollywood Blvd.

Italian postcard by C.C.M., no. 11, distributed in Belgium by Victoria, Bruxelles. Photo: RKO Radio Films.

Italian postcard by Bromofoto, Milano, no. 222.

West-German postcard by Starfoto Hasemann, no. 225. Photo: Paramount Pictures.

West-German postcard by Kunst und Bild, Berlin, no. A 300. Photo: Paramount-Film.

British postcard in 'The People' series by Show Parade Picture Service, London, no. P 1127. Photo: Paramount. Hedy Lamarr in Copper Ranyon (John Farrow, 1950).

West-German postcard by H.S.K.-Verlag, Köln (Cologne), no. 501. Photo: Paramount. Ray Milland and Hedy Lamarr in Copper Canyon (John Farrow, 1950).

American postcard by Longshaw Card Co., Los Angeles, Calif, no. 821. Photo: John Hughes. Caption: Home of Hedy Lamarr.

West-German postcard in the 161 Andy Warhol series by Gebr. König Postkartenverlag, Köln, no. 161/4 (4 of 10), 1989. Illustration: Andy Warhol. Caption: Hedy Lamarr, 1962.

Sources: Jan Christopher Horak (CineAction), David Thomson (The Independent), HedyLamarr.com, Wikipedia, and IMDb.

This post was last updated on 25 June 2021.

I love the way you've woven the postcard, vintage video and comment together. Very information AND interesting post.

ReplyDeleteEvelyn in Montreal

what a sad life for a beautiful lady. I never knew.

ReplyDelete