Dutch actress Nola Hatterman (1899-1984) was mainly a stage performer but also played minor parts in five Dutch silent films. From 1925 on, Hatterman worked as an artist who liked to paint people of colour, in particular Afro-Surinamese. During the war, the Nazis considered her paintings of blues singers and black men dancing as ‘Entartete Kunst’.

Dutch postcard by NRM, no. 911. Photo: J. Merkelbach.

Nola Henderika Petronella Hatterman was born in Amsterdam, on August 12, 1899. She was the only child of Johan Herman Rudolph Hatterman and Elisabeth Hendrika Christina Verzijl, and grew up in Watergraafsmeer, now part of Amsterdam. Nola Hatterman’s father worked for a Dutch East Indies commercial company, and as a consequence, she met people of colour from the Dutch East Indies, laying the base for her interest in the position but also the depiction of people of colour.

Hatterman attended the theatre academy. As a stage actress, she worked at Het Rotterdams Toneel, Koninklijke Vereeniging Het Nederlandsch Tooneel (KVHNT), Jacques Sluijters company, and Nederlands Vaudevillegezelschap. However, she never played major roles on stage. As a film actress, she performed in five silent Dutch films. The first, Majoor Frans (Maurits Binger, 1916) was a Hollandia film production based on the book by Anna Bosboom-Toussaint. For a long time, the film was considered to be lost. In 1994 the Netherlands Filmmuseum (EYE) found some reels of the film in a private collection, which the museum had acquired. The film was incomplete and in a bad state but Majoor Frans was restored. The restored version was first screened in 2000.

Silent film star Annie Bos starred as Majoor Frans, a girl raised as a boy to secure a heritage. Nola Hatterman played a circus girl. Co-stars were Louis Chrispijn, Willem van der Veer, Fred Vogeding and Lily Bouwmeester. Helleveeg/Bitch (Theo Frenkel senior, 1920) starred Mien Duymaer van Twist as a ‘golddigger’ who marries a Dutchman (Co Balfoort) to rise the social ladder. She shocks the man’s family and friends and ruins the man’s daughter’s (Lily Bouwmeester) engagement. In the end, she is strangled by the man’s brother (Frits Fuchs). Nola Hatterman played a nursemaid.

Helleveeg premiered in the Netherlands on the very same day as another film by Frenkel in which Hatterman acted: Geeft ons kracht/Give Us Strength (Theo Frenkel senior, 1920). In this film, Hatterman plays a major part as the sweetheart of a convict (Joop van Hulzen) who killed her out of jealousy. His lawyer (Co Bafoort) sees a parallel with his own affair with an adventuress (Vera van Haeften). Both of Frenkel's films are lost.

A film which still exists is the little-known – and rather outdated – one-reel farce De bolsjewiek/The Bolshevik (Theo Frenkel senior, 1920), in which Hatterman played the maid of a young widow (Vera van Haeften), which takes an amateur plumber (Daan van Nieuwenhuyzen) for her rich cousin from the States. Director Frenkel had no studio, so the wind blew over the set. Drunken, the plumber blows up the house, similar to Pathé and Gaumont farces of 10 years before. Hatterman’s last film was the popular so-called 'Jordaan comedy' Oranje Hein/Orange Henry (Alex Benno, 1925), based on a play by Herman Bouber. The starring roles were played by Johan Elsensohn, Aaf Bouber, the wife of playwright Herman Bouber, Maurits de Vries (Hatterman’s later husband) and Vera van Haeften. Unknown is what Hatterman’s part was. The film is considered lost.

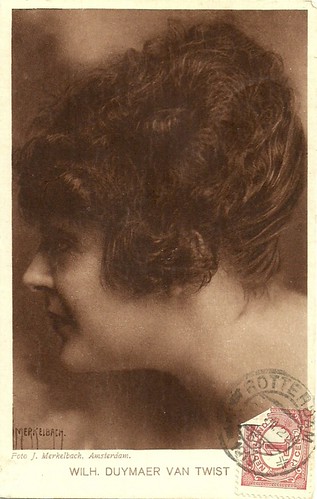

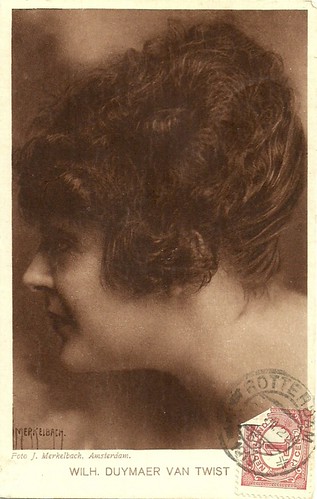

Mien Duymaer van Twist. Dutch postcard. Photo J. Merkelbach, Amsterdam.

After her film and stage career ended, Nola Hatterman chose to be a full-time painter in 1925. She didn’t study at an art academy but took private lessons from Charles Haak, who was employed at the Instituut voor Kunstnijverheidsonderwijs (Education in Applied Arts), now the Rietveld Academie. Nola contributed to group exhibitions of Amsterdam art societies: De Onafhankelijken (already from 1919), St. Lucas (from 1927) and De Brug (from 1930). Her works from the 1920s-1930s clearly have traits of New Objectivity.

Hatterman liked to paint people of colour, in particular Afro-Surinamese. Thanks to Haak she met Surinam people who modelled for her. In 1930 she painted her most famous work, 'Het terras' (The Terrace), depicting the Surinam tap dancer, boxer, model and barkeeper Jimmy van der Lak. The work is related to New Objectivity and is now in the collection of the Amsterdam Stedelijk Museum. In 1939 Hatterman had her first solo exhibition, where she had to defend her focus on black men – something the renowned Dutch painter Jan Sluyters, who also had painted black people, never had to do. After an affair with Dick/Dirk van Veen, in 1929 Hatterman went to live together with Maurits de Vries, known as an actor but also director of the Jordaan comedy 'De Jantjes' and author of the novel 'De man zonder moraal' (The Man Without Morals). In 1931 they married, but apparently, the difference in age and temper (Hatterman was a very lively character) caused Hatterman to leave him in 1938 and move in with artist Arie de Vries, who lived not far from Falckstraat, where Hatterman had her studio.

In September 1940, when the Germans had already occupied the Netherlands, she officially divorced De Vries. The Jewish De Vries went into hiding thanks to his new girlfriend Cor Krienen, who ran a boarding house. Hatterman’s paintings of blues singers and Surinam black men dancing were considered ‘Entartete Kunst’ by the Nazis. During the war, she housed various Surinam people in her house on Falckstraat 9. After the war, Hatterman’s realist style estranged her from young art circles. Because of her cultural-political engagement, she was asked to contribute to the first post-war exhibition at the Amsterdam Stedelijk Museum in 1945, 'Kunst in vrijheid' (Art in Liberation), and in 1950 she had her own exhibition in London, including a black Christ mourned by his mother, which newspaper Daily Herald called 'Europe’s most controversial painting'.

Her house had become the sweeping centre of the Surinam cultural-nationalist movement Wie Eegie Sanie (Our Own Thing), founded in 1951. In 1953 she so longed for Surinam that she moved there. She arrived in Surinam without a penny in her pocket, but she was helped by families and started to teach pottery lessons to rich black and white ladies. Quickly she established herself as a cherished visual artist in Surinam. She didn’t get rich with her art but Hatterman became a respected artist and personality. She also opened a school for painting, becoming one of the founders of art education in the country. In the 1960s-1980s many of her pupils went to the Netherlands and elsewhere in Europe to pursue careers as artists.

Nola Hatterman died in 1984, because of a car accident, on the road between her house in Brokopondo and Paramaribo. After her death, former students founded the Nola Hatterman Institute, where thousands of children were taught painting and drawing. In 1982 Frank Zichem made a documentary about her, Nola, de konsekwente keuze/Nola, the Consequent Choice. In 1997 the gallery exploited by Vereniging Ons Suriname was named after her. Yearly, an artist attached to the Nola Hatterman Institute is enabled to exhibit there. The Nola Hatterman Institute, part of the Fort Zeelandia complex, was fully restored between 2004 and 2005. In 2008 Ellen de Vries published 'Nola, portret van een eigenzinnige kunstenares' (Nola, Portrait of a Headstrong Artist).

Louis Chrispijn. Dutch postcard by Weenenk & Snel, Den Haag. Photo: Willem Coret.

Sources: Geoffrey Donaldson (Of Joy and Sorrow), Nolahatterman.nl (Dutch), Film in nederland.nl (now defunct), DBNL, Wikipedia (Dutch and French) and IMDb. And our special thanks to Gé Joosten.

This post was last updated on 26 August 2024.

Dutch postcard by NRM, no. 911. Photo: J. Merkelbach.

Lost films

Nola Henderika Petronella Hatterman was born in Amsterdam, on August 12, 1899. She was the only child of Johan Herman Rudolph Hatterman and Elisabeth Hendrika Christina Verzijl, and grew up in Watergraafsmeer, now part of Amsterdam. Nola Hatterman’s father worked for a Dutch East Indies commercial company, and as a consequence, she met people of colour from the Dutch East Indies, laying the base for her interest in the position but also the depiction of people of colour.

Hatterman attended the theatre academy. As a stage actress, she worked at Het Rotterdams Toneel, Koninklijke Vereeniging Het Nederlandsch Tooneel (KVHNT), Jacques Sluijters company, and Nederlands Vaudevillegezelschap. However, she never played major roles on stage. As a film actress, she performed in five silent Dutch films. The first, Majoor Frans (Maurits Binger, 1916) was a Hollandia film production based on the book by Anna Bosboom-Toussaint. For a long time, the film was considered to be lost. In 1994 the Netherlands Filmmuseum (EYE) found some reels of the film in a private collection, which the museum had acquired. The film was incomplete and in a bad state but Majoor Frans was restored. The restored version was first screened in 2000.

Silent film star Annie Bos starred as Majoor Frans, a girl raised as a boy to secure a heritage. Nola Hatterman played a circus girl. Co-stars were Louis Chrispijn, Willem van der Veer, Fred Vogeding and Lily Bouwmeester. Helleveeg/Bitch (Theo Frenkel senior, 1920) starred Mien Duymaer van Twist as a ‘golddigger’ who marries a Dutchman (Co Balfoort) to rise the social ladder. She shocks the man’s family and friends and ruins the man’s daughter’s (Lily Bouwmeester) engagement. In the end, she is strangled by the man’s brother (Frits Fuchs). Nola Hatterman played a nursemaid.

Helleveeg premiered in the Netherlands on the very same day as another film by Frenkel in which Hatterman acted: Geeft ons kracht/Give Us Strength (Theo Frenkel senior, 1920). In this film, Hatterman plays a major part as the sweetheart of a convict (Joop van Hulzen) who killed her out of jealousy. His lawyer (Co Bafoort) sees a parallel with his own affair with an adventuress (Vera van Haeften). Both of Frenkel's films are lost.

A film which still exists is the little-known – and rather outdated – one-reel farce De bolsjewiek/The Bolshevik (Theo Frenkel senior, 1920), in which Hatterman played the maid of a young widow (Vera van Haeften), which takes an amateur plumber (Daan van Nieuwenhuyzen) for her rich cousin from the States. Director Frenkel had no studio, so the wind blew over the set. Drunken, the plumber blows up the house, similar to Pathé and Gaumont farces of 10 years before. Hatterman’s last film was the popular so-called 'Jordaan comedy' Oranje Hein/Orange Henry (Alex Benno, 1925), based on a play by Herman Bouber. The starring roles were played by Johan Elsensohn, Aaf Bouber, the wife of playwright Herman Bouber, Maurits de Vries (Hatterman’s later husband) and Vera van Haeften. Unknown is what Hatterman’s part was. The film is considered lost.

Mien Duymaer van Twist. Dutch postcard. Photo J. Merkelbach, Amsterdam.

Europe’s most controversial painting

After her film and stage career ended, Nola Hatterman chose to be a full-time painter in 1925. She didn’t study at an art academy but took private lessons from Charles Haak, who was employed at the Instituut voor Kunstnijverheidsonderwijs (Education in Applied Arts), now the Rietveld Academie. Nola contributed to group exhibitions of Amsterdam art societies: De Onafhankelijken (already from 1919), St. Lucas (from 1927) and De Brug (from 1930). Her works from the 1920s-1930s clearly have traits of New Objectivity.

Hatterman liked to paint people of colour, in particular Afro-Surinamese. Thanks to Haak she met Surinam people who modelled for her. In 1930 she painted her most famous work, 'Het terras' (The Terrace), depicting the Surinam tap dancer, boxer, model and barkeeper Jimmy van der Lak. The work is related to New Objectivity and is now in the collection of the Amsterdam Stedelijk Museum. In 1939 Hatterman had her first solo exhibition, where she had to defend her focus on black men – something the renowned Dutch painter Jan Sluyters, who also had painted black people, never had to do. After an affair with Dick/Dirk van Veen, in 1929 Hatterman went to live together with Maurits de Vries, known as an actor but also director of the Jordaan comedy 'De Jantjes' and author of the novel 'De man zonder moraal' (The Man Without Morals). In 1931 they married, but apparently, the difference in age and temper (Hatterman was a very lively character) caused Hatterman to leave him in 1938 and move in with artist Arie de Vries, who lived not far from Falckstraat, where Hatterman had her studio.

In September 1940, when the Germans had already occupied the Netherlands, she officially divorced De Vries. The Jewish De Vries went into hiding thanks to his new girlfriend Cor Krienen, who ran a boarding house. Hatterman’s paintings of blues singers and Surinam black men dancing were considered ‘Entartete Kunst’ by the Nazis. During the war, she housed various Surinam people in her house on Falckstraat 9. After the war, Hatterman’s realist style estranged her from young art circles. Because of her cultural-political engagement, she was asked to contribute to the first post-war exhibition at the Amsterdam Stedelijk Museum in 1945, 'Kunst in vrijheid' (Art in Liberation), and in 1950 she had her own exhibition in London, including a black Christ mourned by his mother, which newspaper Daily Herald called 'Europe’s most controversial painting'.

Her house had become the sweeping centre of the Surinam cultural-nationalist movement Wie Eegie Sanie (Our Own Thing), founded in 1951. In 1953 she so longed for Surinam that she moved there. She arrived in Surinam without a penny in her pocket, but she was helped by families and started to teach pottery lessons to rich black and white ladies. Quickly she established herself as a cherished visual artist in Surinam. She didn’t get rich with her art but Hatterman became a respected artist and personality. She also opened a school for painting, becoming one of the founders of art education in the country. In the 1960s-1980s many of her pupils went to the Netherlands and elsewhere in Europe to pursue careers as artists.

Nola Hatterman died in 1984, because of a car accident, on the road between her house in Brokopondo and Paramaribo. After her death, former students founded the Nola Hatterman Institute, where thousands of children were taught painting and drawing. In 1982 Frank Zichem made a documentary about her, Nola, de konsekwente keuze/Nola, the Consequent Choice. In 1997 the gallery exploited by Vereniging Ons Suriname was named after her. Yearly, an artist attached to the Nola Hatterman Institute is enabled to exhibit there. The Nola Hatterman Institute, part of the Fort Zeelandia complex, was fully restored between 2004 and 2005. In 2008 Ellen de Vries published 'Nola, portret van een eigenzinnige kunstenares' (Nola, Portrait of a Headstrong Artist).

Louis Chrispijn. Dutch postcard by Weenenk & Snel, Den Haag. Photo: Willem Coret.

Sources: Geoffrey Donaldson (Of Joy and Sorrow), Nolahatterman.nl (Dutch), Film in nederland.nl (now defunct), DBNL, Wikipedia (Dutch and French) and IMDb. And our special thanks to Gé Joosten.

This post was last updated on 26 August 2024.

No comments:

Post a Comment