The career of English stage and film actor Claude Rains (1889-1967) spanned 47 years. In Hollywood, he was a supporting actor who achieved A-list stardom. With his smooth, distinguished voice, he could portray a wide variety of roles, ranging from villains to sympathetic gentlemen. He is best known as the title figure in The Invisible Man (1933), as wicked Prince John in The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938), as a corrupt senator in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939), and, of course, as Captain Renault in Casablanca (1942).

British postcard in the Picturegoer Series, London, no. 917a. Photo: First National.

Italian postcard in the Artisti del Cinema Series, no. 100, by Edizione ELAH, La vasa delle Caramelle. Photo: Warner Bros. Publicity still for They Won't Forget (Mervyn LeRoy, 1937).

German postcard by Pwc-Verlag, München (Munich) from the Prestel-book 'Fashion in Film. Claude Rains, Humphrey Bogart, Paul Henreid and Ingrid Bergman in Casablanca (Michael Curtiz, 1942). Caption: Costumes by Orri-Kelly.

German collector card. Photo: RKO Radio Film. Ingrid Bergman and Claude Rains in Notorious (Alfred Hitchcock, 1946).

William Claude Rains was born in Camberwell, London, in 1889. His father was the English stage actor and later film director Frederick Rains. In 2008, his daughter Jessica Rains and David J. Skal would publish the biography 'Claude Rains: An Actor's Voice'. According to Jessica, he grew up with "a very serious cockney accent and a speech impediment". In 1900, the 11-year-old Rains made his stage debut as a boy singer in 'Sweet Nell of Old Drury'. He learned the technical end of the business by working his way up from being a two-dollar-a-week page boy to assistant stage manager at His Majesty's Theatre in London.

In 1911, he made his adult stage debut in 'Gods of the Mountains'. His acting talents were recognised by Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree, founder of The Royal Academy of Dramatic Art. Tree paid for the elocution lessons Rains needed to succeed as an actor. After making his American stage debut in a tour with Granville Barker's troupe in 'Androcles and the Lion', Rains returned to England.

He served in the First World War in the London Scottish Regiment, with fellow actors Basil Rathbone, Ronald Colman and Herbert Marshall. Rains was involved in a gas attack that left him nearly blind in one eye for the rest of his life. However, the war did aid his social advancement and, by its end, he had risen from the rank of Private to Captain.

Rains began his career in the London theatre, having a success in the title role of John Drinkwater's play 'Ulysses S. Grant', the follow-up to the playwright's major hit 'Abraham Lincoln'. His one and only silent film venture was a small part in the British production Build Thy House (Fred Goodwins, 1920) starring Henry Ainley and Warwick Ward. This film is now considered lost.

In the 1920s, Rains taught at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art. Among his pupils were John Gielgud, Laurence Olivier, and the lovely Isabel Jeans, who became the first of his six wives. In 1926, he travelled again to the USA on tour with the play 'The Constant Nymph', and he decided to stay. In the following years, he played leading roles with the Theatre Guild on Broadway in such plays as George Bernard Shaw's 'The Apple Cart' and in the dramatisation of Pearl S. Buck's novel The Good Earth.

British postcard in the Filmshots series by Film Weekly. Photo: Universal. Claude Rains and William Harrigan in The Invisible Man (James Whale, 1933).

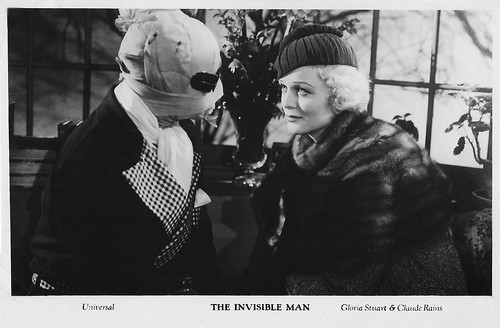

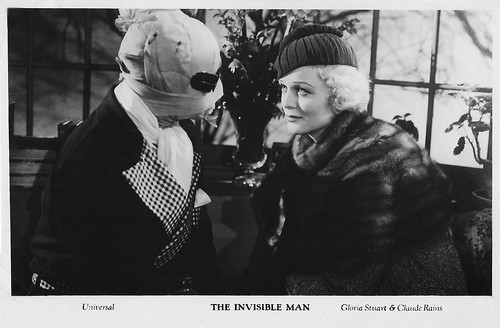

British postcard in the Filmshots series by Film Weekly. Photo: Universal. Gloria Stuart and Claude Rains in The Invisible Man (James Whale, 1933).

Dutch postcard by HEMO. Photo: Eagle Lion. Publicity still for Caesar and Cleopatra (Gabriel Pascal, 1945).

German collector card. Photo: RKO Radio Film. Ingrid Bergman, Claude Rains and Leopoldine Konstantin in Notorious (Alfred Hitchcock, 1946).

Claude Rains came relatively late to film acting, when he had already reached middle age and established himself as an accomplished stage actor. In 1932, while working for the Theatre Guild, Universal Pictures offered him a screen test for a role in A Bill of Divorcement (1933), a part he had already played with considerable conviction on the stage in 1921. Rains had a unique and solid British voice - deep, slightly rasping - but richly dynamic. And as a man of small stature, the combination was immediately intriguing.

Although his screen test was a failure, his distinctive voice won him the title role in the classic fantasy film The Invisible Man (James Whale, 1933), based on the novel by H.G. Wells, when someone accidentally overheard his screen test being played in the next room. In The Invisible Man, Rains was kept from view behind gauze bandages and through the magic of special effects. His face appears only briefly, after the character's death renders him visible again, but the strength of his vocal performance alone launched the actor's career in Hollywood.

William McPeak writes at IMDb: “He took the role by the ears, churning up a rasping malice and volume in his voice to achieve a bone-chilling persona of the disembodied mad doctor. He could also throw out a high-pitched maniac laugh that would make you leave the lights on before going to bed.“ At AllMovie, Hal Erickson added: “So forceful was Rains' verbal performance as 'The Invisible One' that he became an overnight movie star (after nearly twenty years on stage). Wittily scripted by R.C. Sherriff and an uncredited Philip Wylie, and brilliantly directed by James Whale, The Invisible Man is a near-untoppable combination of horror and humour.”

Following his sensational talking-picture debut, Universal Studios tried to typecast Rains in Horror films, but he appeared instead in such interesting films as the Paramount production Crime Without Passion (Ben Hecht, Charles MacArthur, 1934), in which he portrays a man driven to the brink of madness by an unhappy love affair. Rains would play similar characters in subsequent films, as his reserved, ironic manner proved an ideal mask for slowly crumbling sanity. In Britain, he starred as The Clairvoyant (Maurice Elvey, 1935). By 1936, he was at Warner Bros. with its ambitious laundry list of literary epics in full swing. His malicious, gouty Don Luis in Anthony Adverse (Mervyn LeRoy, Michael Curtiz (uncredited), 1936) was inspired. After a sheer lucky opportunity to dispatch his young wife's lover, Louis Hayward, in a duel, he triumphs over her in a scene with derisive, bulging eyes and that high-pitched laugh - with appropriate shadow and light backdrop - that is unforgettable.

Another success was his gleefully evil role of Prince John in The Adventures of Robin Hood (Michael Curtiz, William Keighley, 1938). Rains later credited director Michael Curtiz with teaching him the more understated requirements of film acting, or "what not to do in front of a camera". In 1939, Rains became an American citizen. He was also, for the first time, nominated for the Academy Award for his performance as the complex, ethics-tortured senator in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (Frank Capra, 1939). Janet E. Lorenz writes at Film Reference: “His performance in the Capra film exemplifies Rains' ability to portray characters who remain charming — and sometimes sympathetic — in spite of their actions.”

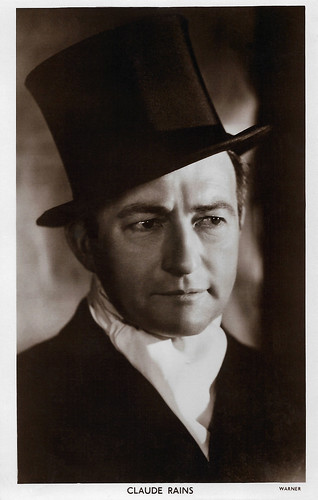

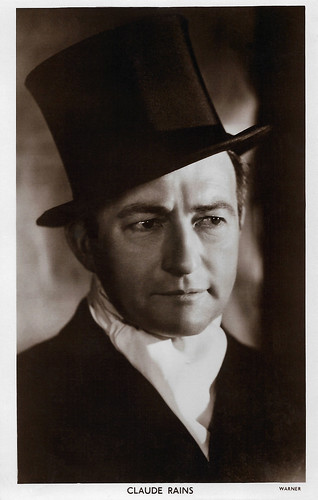

British postcard by the Picturegoer Series, London, no. B.8. Photo: Warner.

Spanish postcard, Series 4021, no. 69.

British postcard in the Picturegoer Series, London, no. 917. Photo: Paramount.

Claude Rains’ most famous role is the flexible French police Captain Renault in Casablanca (Michael Curtiz, 1942). The next year, he played the disfigured music lover who haunts the Paris Opera house in Universal's full-colour remake of Phantom of the Opera (Arthur Lubin, 1943). Bette Davis named him her favourite co-star, and they made four films together. Janet E. Lorentz: “In Now, Voyager (Irving Rapper, 1942), one of the classic ‘women's films’ of the 1940s, he portrays Davis's wise, understanding psychiatrist, while his performance as her adoring, long-suffering husband in Mr. Skeffington (Vincent Sherman, 1944) brought him another Oscar nomination. The pairing of Davis's electric screen presence with Rains' precise, assured style lends a particular chemistry to their films together.”

Rains became the first actor to receive a million-dollar salary, playing Julius Caesar opposite Vivien Leigh in the lavish and unsuccessful version of George Bernard Shaw's Caesar and Cleopatra (Gabriel Pascal, 1945), made in Britain. In 1946, he played a nervous and malignant refugee Nazi agent in the classic thriller Notorious (Alfred Hitchcock, 1946). Nick Zegarac wrote at The Hollywood Art: “a stylish entrée in which, as a suave Nazi supporter living in Mexico City, he attempted to poison his wife (Ingrid Bergman) under the watchful eye of an FBI agent (Cary Grant). A formidable success at the box office, the film seemed to place Rains in the envious position to draw star billing once more.” Four years later, he appeared in The Passionate Friends (David Lean, 1949) with Ann Todd and Trevor Howard.

Claude Rains remained a popular character actor in the 1950s and 1960s, appearing in many films. In 1951, he made a triumphant return to Broadway in Darkness at Noon, for which he won the Tony Award. The next year, he starred as the title figure in the British film The Man Who Watched Trains Go By (Harold French, 1952). His only singing and dancing role was in a television musical version of The Pied Piper of Hamelin (Bretaigne Windust, 1957), with Van Johnson as the Piper. This NBC colour special, shown as a film rather than a live or videotaped program, was highly successful with the public. Sold into syndication after its first telecast, it was repeated annually by many local TV stations. As a favoured Alfred Hitchcock alumnus, he starred in five Alfred Hitchcock Presents (1956-1962) suspense dramas.

Two of Rains’ well-known later screen roles were as Dryden, a cynical British diplomat in Lawrence of Arabia (David Lean, 1962), featuring Peter O’Toole, and King Herod in The Greatest Story Ever Told (George Stevens, 1965) with Max von Sydow. The latter was his final film role. Rains made several audio recordings, narrating a few Bible stories for children on Capitol Records, and reciting Richard Strauss' setting for narrator and piano of Tennyson's poem Enoch Arden, with the piano solos played by Glenn Gould. This recording was made by Columbia Masterworks Records.

Claude Rains married six times, the first five of which ended in divorce: actress Isabel Jeans (1913–1915); Marie Hemingway (1920, for less than a year); Beatrix Thomson (1924-1935); Frances Proper (1935–1956); and to classic pianist Agi Jambor (1959–1960). He married Rosemary Clark Schrode in 1960 and stayed with her until she died in 1964. His only child, Jessica Rains, was born to him and Proper in 1938. Rains died from an abdominal haemorrhage in Laconia, New Hampshire, in 1967 at the age of 77. He was nominated four times for the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor, for Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939), Casablanca (1942), Mr. Skeffington (1944), and Notorious (1946). Surprisingly, he never won.

British Real Photograph postcard, no. 236. Photo: Warner Bros.

British postcard in the Picturegoer Series, London, no. 712 W. Photo: Paramount.

Trailer for The Passionate Friends (1949). Source: K8nairne (YouTube).

Sources: Janet E. Lorenz (Film Reference), Hal Erickson (AllMovie - Page now defunct), Nick Zegarassc (The Hollywood Art - Now defunct), William McPeak (IMDb), Brian McFarlane (Encyclopedia of British Film), Donald Greyfield (Find a Grave), Wikipedia, and IMDb.

British postcard in the Picturegoer Series, London, no. 917a. Photo: First National.

Italian postcard in the Artisti del Cinema Series, no. 100, by Edizione ELAH, La vasa delle Caramelle. Photo: Warner Bros. Publicity still for They Won't Forget (Mervyn LeRoy, 1937).

German postcard by Pwc-Verlag, München (Munich) from the Prestel-book 'Fashion in Film. Claude Rains, Humphrey Bogart, Paul Henreid and Ingrid Bergman in Casablanca (Michael Curtiz, 1942). Caption: Costumes by Orri-Kelly.

German collector card. Photo: RKO Radio Film. Ingrid Bergman and Claude Rains in Notorious (Alfred Hitchcock, 1946).

Gas attack

William Claude Rains was born in Camberwell, London, in 1889. His father was the English stage actor and later film director Frederick Rains. In 2008, his daughter Jessica Rains and David J. Skal would publish the biography 'Claude Rains: An Actor's Voice'. According to Jessica, he grew up with "a very serious cockney accent and a speech impediment". In 1900, the 11-year-old Rains made his stage debut as a boy singer in 'Sweet Nell of Old Drury'. He learned the technical end of the business by working his way up from being a two-dollar-a-week page boy to assistant stage manager at His Majesty's Theatre in London.

In 1911, he made his adult stage debut in 'Gods of the Mountains'. His acting talents were recognised by Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree, founder of The Royal Academy of Dramatic Art. Tree paid for the elocution lessons Rains needed to succeed as an actor. After making his American stage debut in a tour with Granville Barker's troupe in 'Androcles and the Lion', Rains returned to England.

He served in the First World War in the London Scottish Regiment, with fellow actors Basil Rathbone, Ronald Colman and Herbert Marshall. Rains was involved in a gas attack that left him nearly blind in one eye for the rest of his life. However, the war did aid his social advancement and, by its end, he had risen from the rank of Private to Captain.

Rains began his career in the London theatre, having a success in the title role of John Drinkwater's play 'Ulysses S. Grant', the follow-up to the playwright's major hit 'Abraham Lincoln'. His one and only silent film venture was a small part in the British production Build Thy House (Fred Goodwins, 1920) starring Henry Ainley and Warwick Ward. This film is now considered lost.

In the 1920s, Rains taught at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art. Among his pupils were John Gielgud, Laurence Olivier, and the lovely Isabel Jeans, who became the first of his six wives. In 1926, he travelled again to the USA on tour with the play 'The Constant Nymph', and he decided to stay. In the following years, he played leading roles with the Theatre Guild on Broadway in such plays as George Bernard Shaw's 'The Apple Cart' and in the dramatisation of Pearl S. Buck's novel The Good Earth.

British postcard in the Filmshots series by Film Weekly. Photo: Universal. Claude Rains and William Harrigan in The Invisible Man (James Whale, 1933).

British postcard in the Filmshots series by Film Weekly. Photo: Universal. Gloria Stuart and Claude Rains in The Invisible Man (James Whale, 1933).

Dutch postcard by HEMO. Photo: Eagle Lion. Publicity still for Caesar and Cleopatra (Gabriel Pascal, 1945).

German collector card. Photo: RKO Radio Film. Ingrid Bergman, Claude Rains and Leopoldine Konstantin in Notorious (Alfred Hitchcock, 1946).

A unique and solid British voice

Claude Rains came relatively late to film acting, when he had already reached middle age and established himself as an accomplished stage actor. In 1932, while working for the Theatre Guild, Universal Pictures offered him a screen test for a role in A Bill of Divorcement (1933), a part he had already played with considerable conviction on the stage in 1921. Rains had a unique and solid British voice - deep, slightly rasping - but richly dynamic. And as a man of small stature, the combination was immediately intriguing.

Although his screen test was a failure, his distinctive voice won him the title role in the classic fantasy film The Invisible Man (James Whale, 1933), based on the novel by H.G. Wells, when someone accidentally overheard his screen test being played in the next room. In The Invisible Man, Rains was kept from view behind gauze bandages and through the magic of special effects. His face appears only briefly, after the character's death renders him visible again, but the strength of his vocal performance alone launched the actor's career in Hollywood.

William McPeak writes at IMDb: “He took the role by the ears, churning up a rasping malice and volume in his voice to achieve a bone-chilling persona of the disembodied mad doctor. He could also throw out a high-pitched maniac laugh that would make you leave the lights on before going to bed.“ At AllMovie, Hal Erickson added: “So forceful was Rains' verbal performance as 'The Invisible One' that he became an overnight movie star (after nearly twenty years on stage). Wittily scripted by R.C. Sherriff and an uncredited Philip Wylie, and brilliantly directed by James Whale, The Invisible Man is a near-untoppable combination of horror and humour.”

Following his sensational talking-picture debut, Universal Studios tried to typecast Rains in Horror films, but he appeared instead in such interesting films as the Paramount production Crime Without Passion (Ben Hecht, Charles MacArthur, 1934), in which he portrays a man driven to the brink of madness by an unhappy love affair. Rains would play similar characters in subsequent films, as his reserved, ironic manner proved an ideal mask for slowly crumbling sanity. In Britain, he starred as The Clairvoyant (Maurice Elvey, 1935). By 1936, he was at Warner Bros. with its ambitious laundry list of literary epics in full swing. His malicious, gouty Don Luis in Anthony Adverse (Mervyn LeRoy, Michael Curtiz (uncredited), 1936) was inspired. After a sheer lucky opportunity to dispatch his young wife's lover, Louis Hayward, in a duel, he triumphs over her in a scene with derisive, bulging eyes and that high-pitched laugh - with appropriate shadow and light backdrop - that is unforgettable.

Another success was his gleefully evil role of Prince John in The Adventures of Robin Hood (Michael Curtiz, William Keighley, 1938). Rains later credited director Michael Curtiz with teaching him the more understated requirements of film acting, or "what not to do in front of a camera". In 1939, Rains became an American citizen. He was also, for the first time, nominated for the Academy Award for his performance as the complex, ethics-tortured senator in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (Frank Capra, 1939). Janet E. Lorenz writes at Film Reference: “His performance in the Capra film exemplifies Rains' ability to portray characters who remain charming — and sometimes sympathetic — in spite of their actions.”

British postcard by the Picturegoer Series, London, no. B.8. Photo: Warner.

Spanish postcard, Series 4021, no. 69.

British postcard in the Picturegoer Series, London, no. 917. Photo: Paramount.

Bette Davis' favourite co-star

Claude Rains’ most famous role is the flexible French police Captain Renault in Casablanca (Michael Curtiz, 1942). The next year, he played the disfigured music lover who haunts the Paris Opera house in Universal's full-colour remake of Phantom of the Opera (Arthur Lubin, 1943). Bette Davis named him her favourite co-star, and they made four films together. Janet E. Lorentz: “In Now, Voyager (Irving Rapper, 1942), one of the classic ‘women's films’ of the 1940s, he portrays Davis's wise, understanding psychiatrist, while his performance as her adoring, long-suffering husband in Mr. Skeffington (Vincent Sherman, 1944) brought him another Oscar nomination. The pairing of Davis's electric screen presence with Rains' precise, assured style lends a particular chemistry to their films together.”

Rains became the first actor to receive a million-dollar salary, playing Julius Caesar opposite Vivien Leigh in the lavish and unsuccessful version of George Bernard Shaw's Caesar and Cleopatra (Gabriel Pascal, 1945), made in Britain. In 1946, he played a nervous and malignant refugee Nazi agent in the classic thriller Notorious (Alfred Hitchcock, 1946). Nick Zegarac wrote at The Hollywood Art: “a stylish entrée in which, as a suave Nazi supporter living in Mexico City, he attempted to poison his wife (Ingrid Bergman) under the watchful eye of an FBI agent (Cary Grant). A formidable success at the box office, the film seemed to place Rains in the envious position to draw star billing once more.” Four years later, he appeared in The Passionate Friends (David Lean, 1949) with Ann Todd and Trevor Howard.

Claude Rains remained a popular character actor in the 1950s and 1960s, appearing in many films. In 1951, he made a triumphant return to Broadway in Darkness at Noon, for which he won the Tony Award. The next year, he starred as the title figure in the British film The Man Who Watched Trains Go By (Harold French, 1952). His only singing and dancing role was in a television musical version of The Pied Piper of Hamelin (Bretaigne Windust, 1957), with Van Johnson as the Piper. This NBC colour special, shown as a film rather than a live or videotaped program, was highly successful with the public. Sold into syndication after its first telecast, it was repeated annually by many local TV stations. As a favoured Alfred Hitchcock alumnus, he starred in five Alfred Hitchcock Presents (1956-1962) suspense dramas.

Two of Rains’ well-known later screen roles were as Dryden, a cynical British diplomat in Lawrence of Arabia (David Lean, 1962), featuring Peter O’Toole, and King Herod in The Greatest Story Ever Told (George Stevens, 1965) with Max von Sydow. The latter was his final film role. Rains made several audio recordings, narrating a few Bible stories for children on Capitol Records, and reciting Richard Strauss' setting for narrator and piano of Tennyson's poem Enoch Arden, with the piano solos played by Glenn Gould. This recording was made by Columbia Masterworks Records.

Claude Rains married six times, the first five of which ended in divorce: actress Isabel Jeans (1913–1915); Marie Hemingway (1920, for less than a year); Beatrix Thomson (1924-1935); Frances Proper (1935–1956); and to classic pianist Agi Jambor (1959–1960). He married Rosemary Clark Schrode in 1960 and stayed with her until she died in 1964. His only child, Jessica Rains, was born to him and Proper in 1938. Rains died from an abdominal haemorrhage in Laconia, New Hampshire, in 1967 at the age of 77. He was nominated four times for the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor, for Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939), Casablanca (1942), Mr. Skeffington (1944), and Notorious (1946). Surprisingly, he never won.

British Real Photograph postcard, no. 236. Photo: Warner Bros.

British postcard in the Picturegoer Series, London, no. 712 W. Photo: Paramount.

Trailer for The Passionate Friends (1949). Source: K8nairne (YouTube).

Sources: Janet E. Lorenz (Film Reference), Hal Erickson (AllMovie - Page now defunct), Nick Zegarassc (The Hollywood Art - Now defunct), William McPeak (IMDb), Brian McFarlane (Encyclopedia of British Film), Donald Greyfield (Find a Grave), Wikipedia, and IMDb.

No comments:

Post a Comment