Linda Moglia (1896-?) was an Italian actress of the silent screen, who peaked in the late 1910s and early 1920s. Her biggest role was that of Roxane in Cirano di Bergerac (Augusto Genina, 1923).

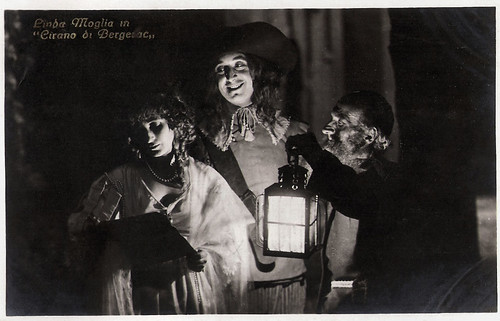

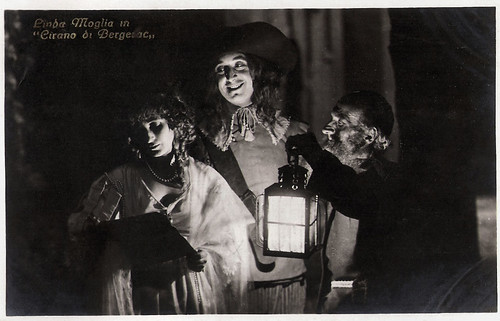

Italian postcard by Ed. A. Traldi, Milano, no. 558.

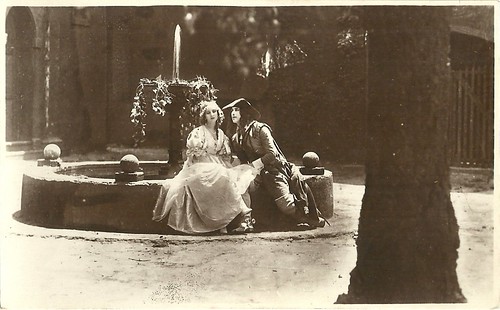

Italian postcard by Fotocelere, Torino, no. 80.

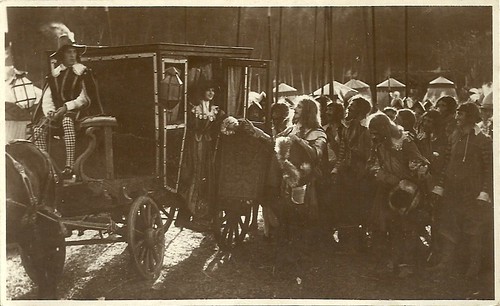

Italian postcard by La Rotofotografica, no. 88.

Linda Moglia was born in 1896 in Turin, Italy.

She probably made her film acting debut in Il doppio volto / The Two-Face (Giulio Antamoro, 1918). This Poli-Film production was adapted from a rather unknown novel by Matilde Serao. It was a modest Neapolitan production with scarce success, but it procured Linda Moglia an entree to the Turin Ambrosio studios.

At Ambrosio, she appeared in Noblesse oblige (1919), based on a French ‘pochade’ by the duo Maurice Hennequin and Pierre Veber, and directed by the famous poster designer Marcello Dudovich. Ambrosio never mentioned his name at the time. Linda starred in the film with her sister Lucia, whose screen name was Lucy Di San Germano or Lucy Sangermano.

After this film, she was the female counterpart to the popular comedian Luciano Manara in the Ambrosio production Il processo Manara (Paolo Trinchera, 1919), which was well received, in contrast to the Gladiator Film production Centocelle (1919), in which Moglia had a supporting part opposite diva Helena Makowska. In particular, the direction by Ugo de Simone was considered the culprit for the tedious and monotonous film.

She then appeared in Maciste innamoratos /Maciste in Love (Luigi Romano Borgnetto, 1919), one of the rare Maciste films in which Maciste has a love affair. Moglia plays Ada, the daughter of an industrialist, who is menaced by revolts and strikes at a time that, also outside of the cinema, Italian society was a place of turmoil. Strongman Maciste (Bartolomeo Pagano) helps to fight the strikers, in particular the few ‘rotten apples’ among them.

Jacqueline Reich writes in her book 'The Maciste Films of Italian Silent Cinema': “Yet, all is not rosy among the workers and the ruling class, as personified in the figure of Ada, who is the mouthpiece of anti-labour sentiment. It is she who voices the fear of the strike –“Lord, no, a strike” – and who calls the workers “scoundrels” as they begin to attack her father, employing the same word in a generalised fashion that her father subsequently uses to characterise only a few nefarious individuals. (…) Her antipathy and resistance to the working and service classes present her as an aloof reactionary.” The journal Cine-fono commented that the film didn’t give Moglia the right place to show her talents, as Maciste dominated everything. So yes, there was a lot to laugh at, but how artistic was it? The Museo Nazionale del Cinema in Turin recently restored the film, and despite its rather dubious political message, it is quite a well-made and enjoyable film.

Italian postcard, no. 580. Collection: Marlene Pilaete.

Italian postcard by Fotocelere, Torino, no. 79.

Italian postcard by Fotocelere, Italia.

Linda Moglia returned to Naples to Poli-Film for Mala Pasqua / Bad Easter (1920). It was directed by actor and director Ignazio Lupi. The story was based on Giovanni Grasso’s play 'Dodici anni dopo' (Twelve Years After), a kind of sequel to the famous 'Cavalleria rusticana' by Giovanni Verga, turned into an opera by Pietro Mascagni. Here Santuzza (Moglia) goes berserk when her son, named Turiddu after his killed father, is lost. Alfio (Giovanni Grasso), released from prison after having killed Turiddu, shows his best side and helps to find the child. Even Alfio’s mother, who had gone mad after the killing, returns to reason. The press called this all too good to be true, but lauded Grasso’s acting as Alfio, plus the care for the setting with the traditional costumes.

Back at Ambrosio, Moglia played the lead in Uomini gialli / Yellow Men (Eugenio Testa, 1920), a ‘Giallo’ on an American girl who suddenly inherits a fortune from a relative who died in Japan. Two Asians try to get the money and force the heiress to marry one of them instead of her fiancé, the painter Borelli (Angelo Vianello). A mysterious man with a black hood (Thenno) helps and unmasks himself as the Japanese consul. Clearly, Ambrosio profited from the European tour of the Japanese Thenno and his troupe of jugglers, acrobats and magicians to enlist them for a film. There is a nitrate of the film at EYE Filmmuseum in Amsterdam, which might have been preserved in the meantime.

In Cavacchioni paladino dei dollari (Umberto Paradisi, 1920), Cavacchioni (lit. Big Buttons, played by Ruggero Capodaglio), the famous fat detective in the Maciste films, lives a quiet village life with his housekeeper Clitemnestra (Léonie Laporte), when a rich American heiress (Moglia) upsets village life. When evildoers, pushed by the housekeeper, want to rob the girl, the detective sets things straight and peace returns to the village.

A totally different film was Il rivale / The Rival (Enrico Roma 1920), based on a script by Gaetano Campanile-Mancini. The film tells about the scoundrel Leonardo (Tullio Carminati), who betrayed his wife, which caused a drama. Desperately, she killed herself. From then on, Leonardo is split in two, while his alter ego is always present and reminds him of his guilt. The story ends mysteriously: the real man flees, but his alter ego remains to keep the memory of the dead woman alive, like a votive lamp. The Italian press quite liked this supernatural story, as opposed to the run-of-the-mill dramas and crime films. The splitting of the personality reminds one a bit of Der Student von Prag / The Student of Prague (Stellan Rye, Paul Wegener, 1913), but in general, in the 1910s and early 1920s, the Doppelganger motif was dear to both mainstream and avant-garde filmmakers.

In Il rivale, Moglia played the man’s mistress, who is married, just like Leonardo. Perhaps motivated by the film, Carminati founded his own film company in Rome, Carminati Film, for which Moglia and he were reunited in Follie/Madness (Enrico Roma, 1920). It is the story of a girl who goes to the city and is overwhelmed by its attractions, but in the end returns to her lover in the village. The press was not impressed with the story, but the critic of La Cine-Fono praised the performances by Carminati and Moglia. The truth in their expression and their precise understanding of the psychology of the characters had high artistic qualities and expressed scenes of great human depth, he wrote.

Italian postcard by G.B. Falci, Milano, no. 226. Photo: UCI. Publicity still for the Franco-Italian historical film Cirano di Bergerac (Augusto Genina, 1923).

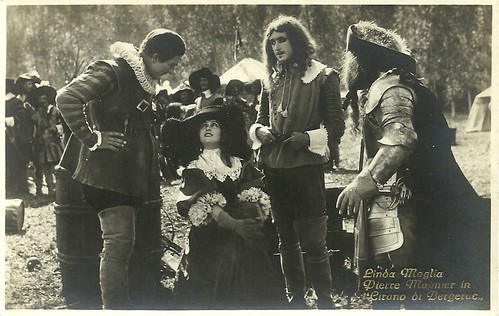

Italian postcard for the Franco-Italian historical film Cirano di Bergerac / Cyrano de Bergerac (Augusto Genina, 1923), with Pierre Magnier as Cyrano de Bergerac, Linda Moglia as Roxane and Angelo Ferrari as Christian de Neuvillette.

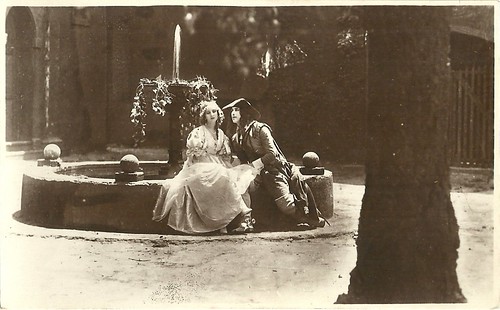

Italian postcard for the Franco-Italian historical film Cirano di Bergerac / Cyrano de Bergerac (Augusto Genina, 1923). Caption: Christian joins the baluster, finally embracing Roxane. He bends towards her mouth to receive the kiss from her, who has bent because of the sweet words Cyrano lent him.

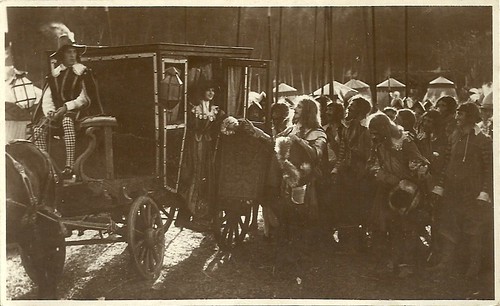

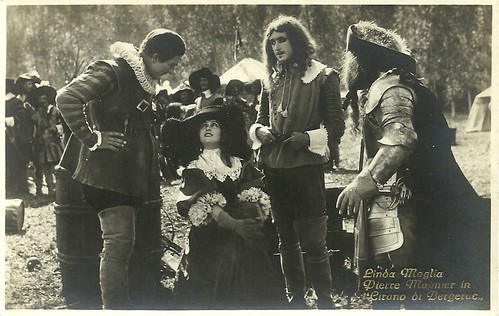

In early 1922, Linda Moglia was taken up by the prestigious historical production Cirano di Bergerac / Cyrano de Bergerac (Augusto Genina, 1923), based on the famous play by Edmond Rostand and scripted by future director Mario Camerini. Genina led a Franco-Italian coproduction with costumes by Caramba and sets by the famous painter Camillo Innocenti. The production had an enormous length and was distributed in a fully stencil coloured version.

The star of the film was Pierre Magnier as Cyrano, the man with the giant nose, while Moglia was his Roxane, his cousin he is deeply in love with, but cannot get because she loves Christian de Neuvillette (Angelo Ferrari). Cirano even helps Christian to write love letters and talk about love. It is only years after, after Christian has died and Cyrano is about to die, that Roxanne discovers the secret, but it's too late.

When presented at the National Film Contest in Turin in 1923, it immediately won the first prize. In 1923, it was first commercially released in Paris, at the Salle Marivaux, where it had an enormous success. Italian distributors, though, retaliated, as they thought the film was too difficult for the audience. Finally, UCI released it in Turin at the end of 1925, and in Rome, even in early 1926. The Italian press blamed the distributors for the unnecessarily long delay. It had been unnecessary, as people flocked to the cinemas in the first weeks. The critics praised the high artistic qualities of the film, first of all, Magnier’s performance.

Strangely enough, Cirano did not result in a breakthrough for Linda Moglia. There followed no foreign offers from France nor elsewhere. Moglia made one last film with Genina as director and with theatre star Ruggero Ruggeri in the lead: the financial drama La moglie bella (Augusto Genina, 1925 in Italy, so even before Cirano ). The story dealt with a wildly speculating banker (Ruggeri), whose spoiled wife (Moglia) has an affair with another banker (Luigi Serventi), until the other financially ruins her husband. Then she realises her husband is the better man.

The press condemned Ruggeri’s acting as 'unfilmic' and Genina’s (art) direction as 'sloppy'. This happened at a time when the Italian film production was falling apart and most film people were leaving for Berlin or Paris, so Moglia may have considered it a good moment to quit. Supporting actress in La moglie bella was Carmen Boni. It was her first film with director Augusto Genina. Boni would become Genina’s new muse and wife during the late 1920s. This might also have played a part in Linda Moglia's decision to retire. After she retired from the cinema, Linda Moglia disappeared, and her date of death is unknown to us. If you have more info, please let us know.

Italian postcard for the Franco-Italian historical film Cirano di Bergerac/ Cyrano de Bergerac (Augusto Genina, 1923), with Linda Moglia as Roxane and Angelo Ferrari as Christian de Neuvillette. Caption: The nice phrases of Christian he learned from Cyrano, have conquered and seduced Roxane.

Italian postcard for the Franco-Italian historical film Cirano di Bergerac / Cyrano de Bergerac (Augusto Genina, 1923), with Linda Moglia as Roxane and Angelo Ferrari as Christian de Neuvillette. Caption: Defying danger, Roxane joins Christian at Arras, where he is camping with the soldiers.

Italian postcard for the Franco-Italian historical film Cirano di Bergerac / Cyrano de Bergerac (Augusto Genina, 1923), with Linda Moglia as Roxane and Angelo Ferrari as Christian de Neuvillette.

Sources: Vittorio Martinelli (Il cinema muto italiano 1918-1924 - Italian), and IMDb. For the gorgeous colours of Cirano di Bergerac / Cyrano de Bergerac (Augusto Genina, 1923), see: Timeline of Historical Film Colours, and I thank you.

This post was last updated on 5 October 2025.

Italian postcard by Ed. A. Traldi, Milano, no. 558.

Italian postcard by Fotocelere, Torino, no. 80.

Italian postcard by La Rotofotografica, no. 88.

Mouthpiece of anti-labour sentiment

Linda Moglia was born in 1896 in Turin, Italy.

She probably made her film acting debut in Il doppio volto / The Two-Face (Giulio Antamoro, 1918). This Poli-Film production was adapted from a rather unknown novel by Matilde Serao. It was a modest Neapolitan production with scarce success, but it procured Linda Moglia an entree to the Turin Ambrosio studios.

At Ambrosio, she appeared in Noblesse oblige (1919), based on a French ‘pochade’ by the duo Maurice Hennequin and Pierre Veber, and directed by the famous poster designer Marcello Dudovich. Ambrosio never mentioned his name at the time. Linda starred in the film with her sister Lucia, whose screen name was Lucy Di San Germano or Lucy Sangermano.

After this film, she was the female counterpart to the popular comedian Luciano Manara in the Ambrosio production Il processo Manara (Paolo Trinchera, 1919), which was well received, in contrast to the Gladiator Film production Centocelle (1919), in which Moglia had a supporting part opposite diva Helena Makowska. In particular, the direction by Ugo de Simone was considered the culprit for the tedious and monotonous film.

She then appeared in Maciste innamoratos /Maciste in Love (Luigi Romano Borgnetto, 1919), one of the rare Maciste films in which Maciste has a love affair. Moglia plays Ada, the daughter of an industrialist, who is menaced by revolts and strikes at a time that, also outside of the cinema, Italian society was a place of turmoil. Strongman Maciste (Bartolomeo Pagano) helps to fight the strikers, in particular the few ‘rotten apples’ among them.

Jacqueline Reich writes in her book 'The Maciste Films of Italian Silent Cinema': “Yet, all is not rosy among the workers and the ruling class, as personified in the figure of Ada, who is the mouthpiece of anti-labour sentiment. It is she who voices the fear of the strike –“Lord, no, a strike” – and who calls the workers “scoundrels” as they begin to attack her father, employing the same word in a generalised fashion that her father subsequently uses to characterise only a few nefarious individuals. (…) Her antipathy and resistance to the working and service classes present her as an aloof reactionary.” The journal Cine-fono commented that the film didn’t give Moglia the right place to show her talents, as Maciste dominated everything. So yes, there was a lot to laugh at, but how artistic was it? The Museo Nazionale del Cinema in Turin recently restored the film, and despite its rather dubious political message, it is quite a well-made and enjoyable film.

Italian postcard, no. 580. Collection: Marlene Pilaete.

Italian postcard by Fotocelere, Torino, no. 79.

Italian postcard by Fotocelere, Italia.

Doppelganger

Linda Moglia returned to Naples to Poli-Film for Mala Pasqua / Bad Easter (1920). It was directed by actor and director Ignazio Lupi. The story was based on Giovanni Grasso’s play 'Dodici anni dopo' (Twelve Years After), a kind of sequel to the famous 'Cavalleria rusticana' by Giovanni Verga, turned into an opera by Pietro Mascagni. Here Santuzza (Moglia) goes berserk when her son, named Turiddu after his killed father, is lost. Alfio (Giovanni Grasso), released from prison after having killed Turiddu, shows his best side and helps to find the child. Even Alfio’s mother, who had gone mad after the killing, returns to reason. The press called this all too good to be true, but lauded Grasso’s acting as Alfio, plus the care for the setting with the traditional costumes.

Back at Ambrosio, Moglia played the lead in Uomini gialli / Yellow Men (Eugenio Testa, 1920), a ‘Giallo’ on an American girl who suddenly inherits a fortune from a relative who died in Japan. Two Asians try to get the money and force the heiress to marry one of them instead of her fiancé, the painter Borelli (Angelo Vianello). A mysterious man with a black hood (Thenno) helps and unmasks himself as the Japanese consul. Clearly, Ambrosio profited from the European tour of the Japanese Thenno and his troupe of jugglers, acrobats and magicians to enlist them for a film. There is a nitrate of the film at EYE Filmmuseum in Amsterdam, which might have been preserved in the meantime.

In Cavacchioni paladino dei dollari (Umberto Paradisi, 1920), Cavacchioni (lit. Big Buttons, played by Ruggero Capodaglio), the famous fat detective in the Maciste films, lives a quiet village life with his housekeeper Clitemnestra (Léonie Laporte), when a rich American heiress (Moglia) upsets village life. When evildoers, pushed by the housekeeper, want to rob the girl, the detective sets things straight and peace returns to the village.

A totally different film was Il rivale / The Rival (Enrico Roma 1920), based on a script by Gaetano Campanile-Mancini. The film tells about the scoundrel Leonardo (Tullio Carminati), who betrayed his wife, which caused a drama. Desperately, she killed herself. From then on, Leonardo is split in two, while his alter ego is always present and reminds him of his guilt. The story ends mysteriously: the real man flees, but his alter ego remains to keep the memory of the dead woman alive, like a votive lamp. The Italian press quite liked this supernatural story, as opposed to the run-of-the-mill dramas and crime films. The splitting of the personality reminds one a bit of Der Student von Prag / The Student of Prague (Stellan Rye, Paul Wegener, 1913), but in general, in the 1910s and early 1920s, the Doppelganger motif was dear to both mainstream and avant-garde filmmakers.

In Il rivale, Moglia played the man’s mistress, who is married, just like Leonardo. Perhaps motivated by the film, Carminati founded his own film company in Rome, Carminati Film, for which Moglia and he were reunited in Follie/Madness (Enrico Roma, 1920). It is the story of a girl who goes to the city and is overwhelmed by its attractions, but in the end returns to her lover in the village. The press was not impressed with the story, but the critic of La Cine-Fono praised the performances by Carminati and Moglia. The truth in their expression and their precise understanding of the psychology of the characters had high artistic qualities and expressed scenes of great human depth, he wrote.

Italian postcard by G.B. Falci, Milano, no. 226. Photo: UCI. Publicity still for the Franco-Italian historical film Cirano di Bergerac (Augusto Genina, 1923).

Italian postcard for the Franco-Italian historical film Cirano di Bergerac / Cyrano de Bergerac (Augusto Genina, 1923), with Pierre Magnier as Cyrano de Bergerac, Linda Moglia as Roxane and Angelo Ferrari as Christian de Neuvillette.

Italian postcard for the Franco-Italian historical film Cirano di Bergerac / Cyrano de Bergerac (Augusto Genina, 1923). Caption: Christian joins the baluster, finally embracing Roxane. He bends towards her mouth to receive the kiss from her, who has bent because of the sweet words Cyrano lent him.

Roxanne

In early 1922, Linda Moglia was taken up by the prestigious historical production Cirano di Bergerac / Cyrano de Bergerac (Augusto Genina, 1923), based on the famous play by Edmond Rostand and scripted by future director Mario Camerini. Genina led a Franco-Italian coproduction with costumes by Caramba and sets by the famous painter Camillo Innocenti. The production had an enormous length and was distributed in a fully stencil coloured version.

The star of the film was Pierre Magnier as Cyrano, the man with the giant nose, while Moglia was his Roxane, his cousin he is deeply in love with, but cannot get because she loves Christian de Neuvillette (Angelo Ferrari). Cirano even helps Christian to write love letters and talk about love. It is only years after, after Christian has died and Cyrano is about to die, that Roxanne discovers the secret, but it's too late.

When presented at the National Film Contest in Turin in 1923, it immediately won the first prize. In 1923, it was first commercially released in Paris, at the Salle Marivaux, where it had an enormous success. Italian distributors, though, retaliated, as they thought the film was too difficult for the audience. Finally, UCI released it in Turin at the end of 1925, and in Rome, even in early 1926. The Italian press blamed the distributors for the unnecessarily long delay. It had been unnecessary, as people flocked to the cinemas in the first weeks. The critics praised the high artistic qualities of the film, first of all, Magnier’s performance.

Strangely enough, Cirano did not result in a breakthrough for Linda Moglia. There followed no foreign offers from France nor elsewhere. Moglia made one last film with Genina as director and with theatre star Ruggero Ruggeri in the lead: the financial drama La moglie bella (Augusto Genina, 1925 in Italy, so even before Cirano ). The story dealt with a wildly speculating banker (Ruggeri), whose spoiled wife (Moglia) has an affair with another banker (Luigi Serventi), until the other financially ruins her husband. Then she realises her husband is the better man.

The press condemned Ruggeri’s acting as 'unfilmic' and Genina’s (art) direction as 'sloppy'. This happened at a time when the Italian film production was falling apart and most film people were leaving for Berlin or Paris, so Moglia may have considered it a good moment to quit. Supporting actress in La moglie bella was Carmen Boni. It was her first film with director Augusto Genina. Boni would become Genina’s new muse and wife during the late 1920s. This might also have played a part in Linda Moglia's decision to retire. After she retired from the cinema, Linda Moglia disappeared, and her date of death is unknown to us. If you have more info, please let us know.

Italian postcard for the Franco-Italian historical film Cirano di Bergerac/ Cyrano de Bergerac (Augusto Genina, 1923), with Linda Moglia as Roxane and Angelo Ferrari as Christian de Neuvillette. Caption: The nice phrases of Christian he learned from Cyrano, have conquered and seduced Roxane.

Italian postcard for the Franco-Italian historical film Cirano di Bergerac / Cyrano de Bergerac (Augusto Genina, 1923), with Linda Moglia as Roxane and Angelo Ferrari as Christian de Neuvillette. Caption: Defying danger, Roxane joins Christian at Arras, where he is camping with the soldiers.

Italian postcard for the Franco-Italian historical film Cirano di Bergerac / Cyrano de Bergerac (Augusto Genina, 1923), with Linda Moglia as Roxane and Angelo Ferrari as Christian de Neuvillette.

Sources: Vittorio Martinelli (Il cinema muto italiano 1918-1924 - Italian), and IMDb. For the gorgeous colours of Cirano di Bergerac / Cyrano de Bergerac (Augusto Genina, 1923), see: Timeline of Historical Film Colours, and I thank you.

This post was last updated on 5 October 2025.

No comments:

Post a Comment