Paramount Pictures is the fifth oldest surviving film studio in the world after the French studios Gaumont Film Company (1895) and Pathé (1896), followed by the Nordisk Film company (1906), and Universal Studios (1912). Paramount Pictures was created in 1916 through the merger of two prominent film production companies, the Famous Players Film Company and the Jesse L. Lasky Feature Play Company, and a nationwide film distributor, Paramount. Film producer Adolph Zukor put 22 actors and actresses under contract and honoured each with a star on the logo. These fortunate few would become the first movie stars. Paramount’s early hits included Blood and Sand (Fred Niblo, 1922) starring Rudolph Valentino, the Western The Covered Wagon (1923), and The Ten Commandments (1923), a biblical epic directed by Cecil B. DeMille. In 1933 the company declared bankruptcy, Lasky was ousted, and the company reorganized to emerge as Paramount Pictures, Inc., with Zukor serving as chairman of the board emeritus. Gulf+Western acquired the company in 1966, followed by Viacom, Inc. in 1994. Today, Paramount is the sole member of the Big Six film studios still headquartered in the Hollywood district of Los Angeles.

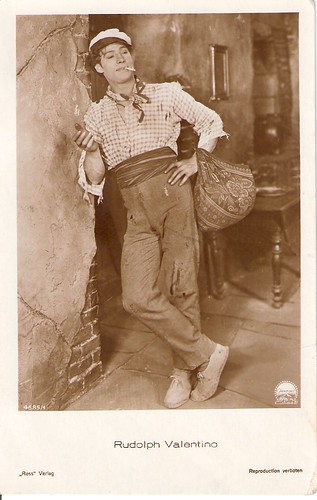

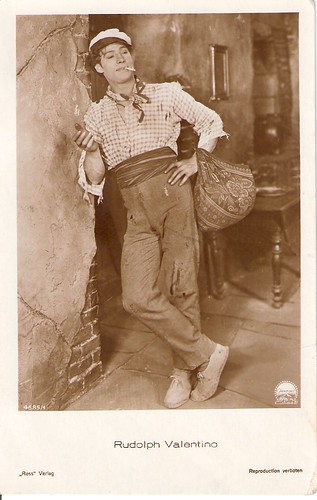

Rudolph Valentino. German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 4685/1, 1929-1930. Photo: Paramount. Publicity still for Blood and Sand (Fred Niblo, 1922).

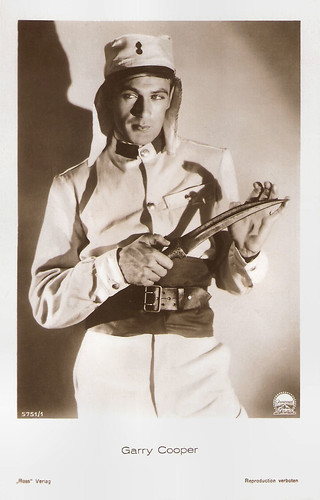

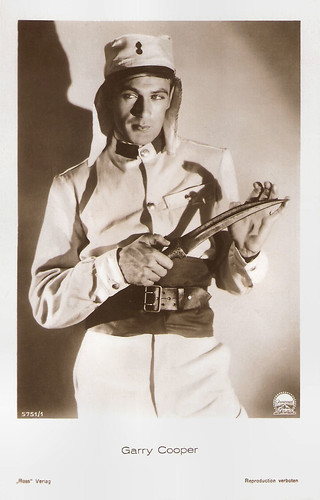

Gary Cooper. German postcard by Ross-Verlag, no. 5751/1, 1930-1931. Photo: Paramount. Publicity still for Morocco (Josef von Sternberg, 1930). Cooper was mistakenly credited as 'Garry Cooper'.

Marlene Dietrich. German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 6673/2, 1931-1932. Photo: Don English / Paramount. Publicity still for Shanghai Express (Josef von Sternberg, 1932).

Veronica Lake. Big Belgian card by Chocolaterie Clovis, Pepinster. Photo: George Hurrell / Paramount. Publicity still for This Gun for Hire (Frank Tuttle, 1942).

Charlton Heston. Dutch postcard by Gebr. Spanjersberg N.V., Rotterdam, no. 5183. Photo: Paramount. Publicity still for The Ten Commandments (Cecil B. DeMille, 1956) with Heston as Moses. Moses' robe was hand-woven by Dorothea Hulse, one of the world's finest weavers. She also created costumes for The Robe, as well as textiles and costume fabrics for Samson and Delilah, David and Bathsheba, and others.

Famous Players was created in 1912 by Adolph Zukor, a Hungarian immigrant who started in the penny arcade and nickelodeon business in New York in the early 1900s. Famous Players enjoyed early success producing and distributing multi-reel (feature-length) films and developing a star-driven market strategy.

With partners Daniel Frohman and Charles Frohman, Zukor planned to make films which appealed to the middle class by featuring the leading theatrical players of the time ('Famous Players in Famous Plays'). By mid-1913, Famous Players had completed five films. Its first film was Les Amours de la reine Élisabeth/Queen Elizabeth (Henri Desfontaines, Louis Mercanton, 1912) which starred Sarah Bernhardt.

Meanwhile, three young filmmaking entrepreneurs, Jesse Lasky, Samuel Goldfish (later Goldwyn), and Cecil B. DeMille, launched a production company in Hollywood in 1913, Jesse L. Lasky Feature Play Company. They scored a major hit in 1914 with their first feature production, The Squaw Man (Oscar Apfel, Cecil B. DeMille, 1914).

That same year, as the movies were rapidly becoming a major entertainment enterprise, W. W. Hodkinson formed a nationwide distribution company, Paramount Pictures, to release the films produced by Famous Players, Lasky, and others. Paramount was the first successful nationwide distributor. Until this time, films were sold on a state-wide or regional basis which had proved costly to film producers. Also, Famous Players and Lasky were privately owned while Paramount was a corporation.

Zukor and Lasky bought Hodkinson out of Paramount, and merged the three companies into one. The new company Lasky and Zukor founded, Famous Players-Lasky Corporation, grew quickly, with Lasky and his partners Goldwyn and DeMille running the production side, Hiram Abrams in charge of distribution, and Zukor making great plans. With only the exhibitor-owned First National as a rival, Famous Players-Lasky and its Paramount Pictures soon dominated the business.

Because Zukor believed in stars, he signed and developed many of the leading early stars, including Mary Pickford, Pauline Frederick, William S. Hart, Douglas Fairbanks, Fatty Arbuckle, Gloria Swanson, and Wallace Reid. With so many important players, Paramount was able to introduce ‘block booking’, which meant that an exhibitor who wanted a particular star's films had to buy a year's worth of other Paramount productions. It was this system that gave Paramount a leading position in the 1920s and 1930s, but which led the government to pursue it on antitrust grounds for more than twenty years.

The studio produced scores of top hits, ranging from Rudolph Valentino vehicles like The Sheik (George Melford, 1921) and Blood and Sand (Fred Niblo, 1922) to Western epics like The Covered Wagon (James Cruze, 1923) and the DeMille spectacles The Ten Commandments (1923) and The King of Kings (1927).

Pola Negri. German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 939/5, 1925-1926. Photo: Paramount-Film. Publicity still for The Cheat (George Fitzmaurice, 1923).

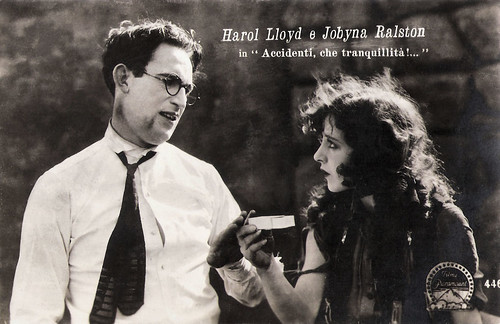

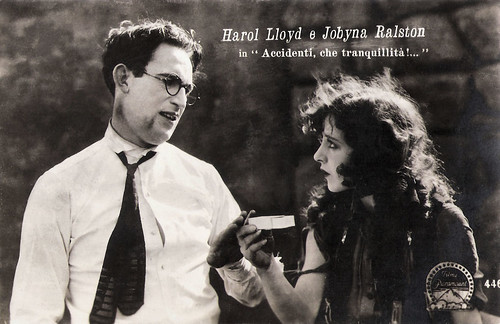

Italian postcard by Casa Editrice Ballerini & Fratini, Firenze (B.F.F.), no. 446. Photo: Paramount. Publicity still for Why Worry (Fred C. Newmeyer, Sam Taylor, 1923) with Harold Lloyd and Jobyna Ralston.

Gloria Swanson. German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 1488/3, 1927-1928. Photo: Paramount / Parafumet. Publicity still for Stage Struck (Allan Dwan, 1925).

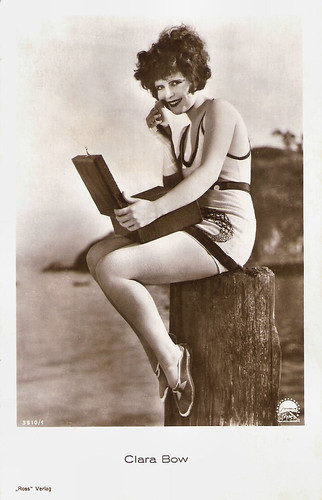

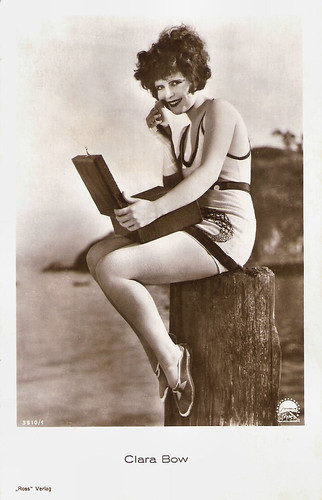

Clara Bow. German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 3510/1, 1928-1929. Photo: Paramount.

Charles Rogers, Nancy Carroll, and Jean Hersholt. German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 111/1. Photo: Paramount. Publicity still for Abie's Irish Rose (Victor Fleming, 1928), which was based on a popular Broadway play.

In 1926, Adolph Zukor hired independent producer B. P. Schulberg, an unerring eye for new talent, to run the film studio. Paramount was one of the first Hollywood studios to release what were known at that time as ‘talkies’, and in 1929, released their first musical, Innocents of Paris (Richard Wallace, 1929). Maurice Chevalier starred and sung the most famous song from the film, Louise.

Eventually, Zukor shed most of his early partners. In 1935, Paramount went bankrupt. Zukor was bumped up to chairman of the board. In this role, he reorganised the company as Paramount Pictures, Inc. and was able to successfully bring the studio out of bankruptcy.

Paramount continued to emphasize stars; in the 1920s there were Swanson, Valentino, and Clara Bow. By the 1930s, talkies brought in a range of powerful new draws: Miriam Hopkins, Marlene Dietrich, Mae West, W.C. Fields, Jeanette MacDonald, Claudette Colbert, Dorothy Lamour, Carole Lombard, Bing Crosby, band leader Shep Fields, famous Argentine tango singer Carlos Gardel, and Gary Cooper among them.

Like the other majors, Paramount's house style was geared to a range of star genre formulas; but the studio was unique in that these generally were handled not by unit producers but by specific directors who were granted considerable creative autonomy and control. Examples are Josef von Sternberg's highly stylized Dietrich melodramas like Morocco (1930), Shanghai Express (1932) and Blonde Venus (1932), and Ernst Lubitsch's distinctive musical operettas with Jeanette MacDonald such as The Love Parade (1929) and One Hour With You (1932).

While the key elements in these star-genre units were director and star, other filmmakers were crucial as well: writer Jules Furthman and cinematographer Lee Garmes on the Dietrich films, for example, and the production design by Hans Dreier on all of the films directed by both Lubitsch and von Sternberg during this period.

In this period Paramount can truly be described as a movie factory, turning out sixty to seventy pictures a year. Such were the benefits of having a huge theatre chain to fill, and of block booking to persuade other chains to go along. The studio's invested heavily in comedy during the early sound era, best typified perhaps by its run of the Marx Brothers comedies: The Cocoanuts (Robert Florey, Joseph Santley, 1929), Animal Crackers (Victor Heerman, 1930), Monkey Business (Norman Z. McLeod, 1931), Horse Feathers (Norman Z. McLeod, 1932), and Duck Soup (Leo McCarey, 1933). The first two films were shot at Paramount's Astoria, New York, studio.

W. C. Fields, George Burns & Gracie Allen, and Jack Oakie also contributed to this comedy trend, whose roots ran deeply into American vaudeville. In 1933, Mae West would add greatly to Paramount's success with her suggestive movies She Done Him Wrong (Lowell Sherman, 1933) and I'm No Angel (Wesley Ruggles, 1933). However, the sex appeal West gave in these movies would also lead to the enforcement of the Production Code, as the newly formed organization the Catholic Legion of Decency threatened a boycott if it was not enforced.

Influential comedy directors were Leo McCarey with Belle of the Nineties (1934) and Ruggles of Red Gap (1935) with Charles Laughton, and, Mitchell Leisen with Easy Living (1937) with Jean Arthur and Ray Milland, and Midnight (1939) with Claudette Colbert.

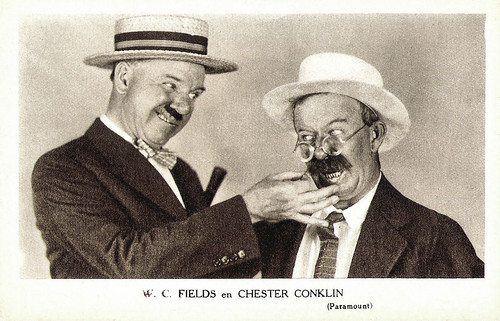

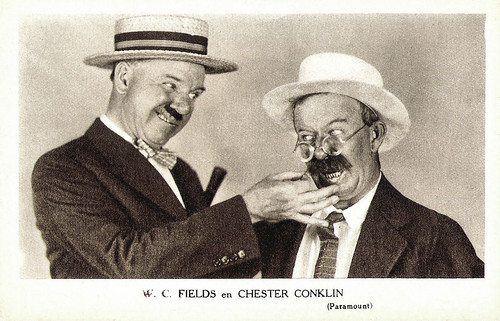

W.C. Fields and Chester Conklin. Dutch card. Photo: Paramount. Publicity still for Fools for Luck (Charles Reisner, 1928).

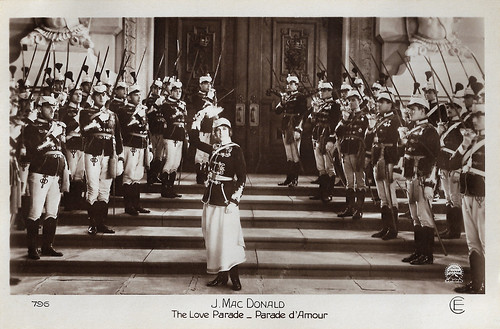

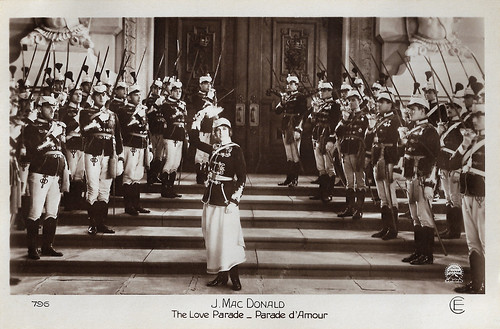

Jeanette MacDonald. French postcard by Cinémagazine-Edition, no. 796. Photo: Paramount. Publicity still for The Love Parade (Ernst Lubitsch, 1929).

Maurice Chevalier. German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 531. Photo: Paramount.

Charles 'Buddy' Rogers and Nancy Carroll. German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 5547/1, 1930-1931. Photo: Paramount. Publicity still for Follow Thru (Lloyd Corrigan, Laurence Schwab, 1930).

Claudette Colbert and Henry Wilcoxon. French postcard by A.N., Paris, no. 962. Photo: Paramount. Publicity still for Cleopatra (Cecil B. DeMille, 1934).

In 1940, Paramount agreed to a government-instituted consent decree: block booking and ‘pre-selling’ (the practice of collecting up-front money for films not yet in production) would end. Immediately, Paramount cut back on production, from 71 films to a more modest 19 annually in the war years.

Still, with more new stars like Bob Hope, Alan Ladd, Veronica Lake, Paulette Goddard, and Betty Hutton, and with war-time attendance at astronomical numbers, Paramount and the other integrated studio-theatre combines made more money than ever.

At this, the Federal Trade Commission and the Justice Department decided to reopen their case against the five integrated studios. This led to the Supreme Court decision United States v. Paramount Pictures, Inc. (1948) holding that movie studios could not also own movie theatre chains. This decision broke up Adolph Zukor's creation, with the theatre chain being split into a new company, United Paramount Theatres, and effectively brought an end to the classic Hollywood studio system.

With the separation of production and exhibition forced by the U.S. Supreme Court, Paramount Pictures Inc. was split in two. Paramount Pictures Corporation was formed to be the production distribution company, with the 1,500-screen theatre chain handed to the new United Paramount Theatres on December 31, 1949. Leonard Goldenson, who had headed the chain since 1938, remained as the new company's president.

Despite such setbacks, Paramount had a number of successes in the 1940s and 1950s, notably the satirical comedies of writer-director Preston Sturges such as The Lady Eve (1941) and Going My Way (1944), the cynical dramas and comedies of writer-director Billy Wilder like Double Indemnity (1944) and Sunset Boulevard (1950), the Road to-comedies of Bob Hope, Bing Crosby, and Dorothy Lamour the Western Shane (1953), and Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window (1954) with James Stewart and Grace Kelly.

With the loss of the theatre chain, Paramount Pictures went into a decline, cutting studio-backed production, releasing its contract players, and making production deals with independents. By the mid-1950s, all the great names were gone. Only Cecil B. DeMille, associated with Paramount since 1913, kept making pictures in the grand old style. Despite Paramount's losses, DeMille would, however, give the studio some relief and create his most successful film at Paramount, a remake of his 1923 film The Ten Commandments (1956), starring Charlton Heston and Yul Brynner. DeMille died in 1959.

Like some other studios, Paramount saw little value in its film library, and sold 764 of its pre-1948 films.

Charles Laughton. Vintage postcard. Photo: Paramount. Publicity still for Ruggles of Red Gap (1935).

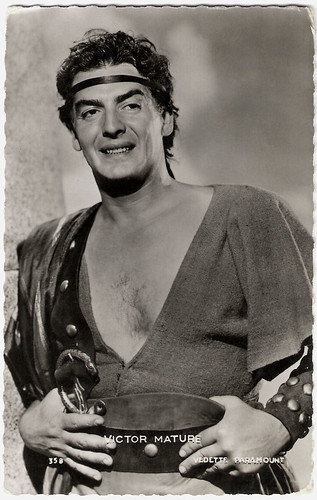

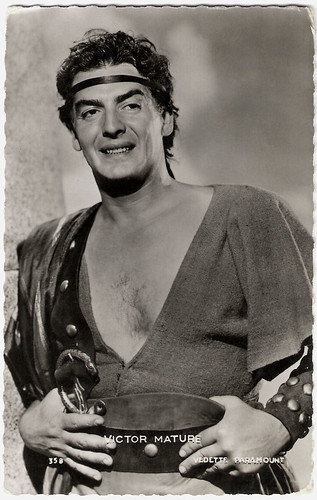

Victor Mature. French postcard by Editions P.I., Paris, no. 358, 1954. Photo: Paramount Pictures Inc.. Publicity still for Samson and Delilah (Cecil B. DeMille, 1949).

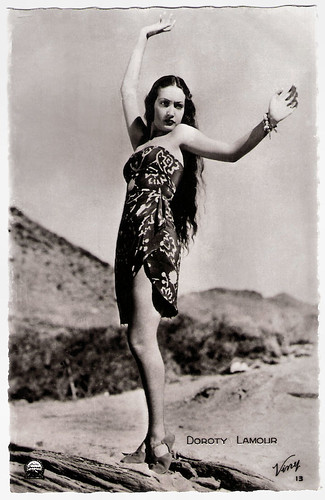

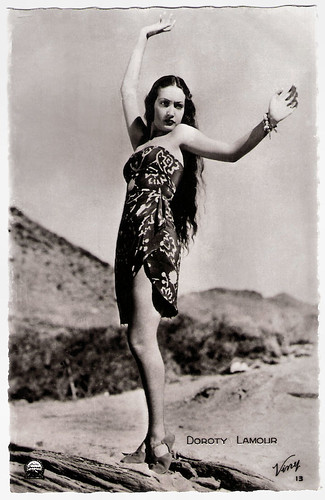

Dorothy Lamour. French postcard by Viny, no. 13. Photo: Paramount.

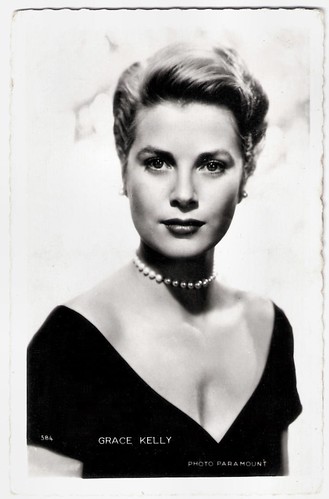

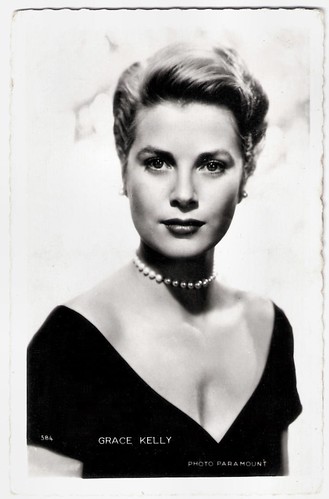

Grace Kelly. French postcard by Editions P.I., Paris, no. 584, Photo: Paramount, 1954.

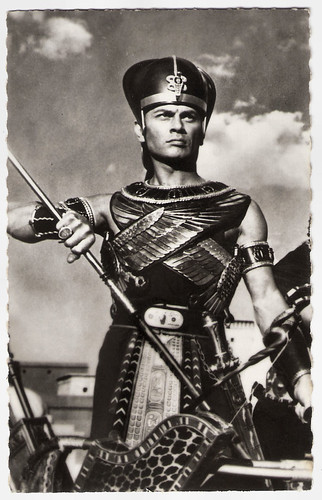

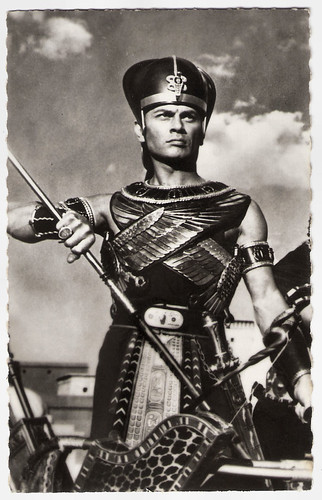

Yul Brynner. French postcard by Editions P.I., Paris, no. 831. Photo: Paramount. Publicity still for The Ten Commandments (Cecil B. DeMille, 1956). For his pursuit of the Israelites, Brynner in his role as Rameses II wears the blue Khepresh helmet-crown, which the pharaohs wore for battle.

By the early 1960s, Paramount's future was doubtful. The high-risk movie business was wobbly; the theatre chain was long gone; investments in television came to nothing; and the Golden Age of Hollywood had just ended. Films of this period include Psycho (Alfred Hitchcock, 1960) and Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961).

In 1966, a sinking Paramount was sold to Charles Bluhdorn's industrial conglomerate, Gulf + Western Industries Corporation. Bluhdorn immediately put his stamp on the studio, installing a virtually unknown producer named Robert Evans as head of production. Despite some rough times, Evans held the job for eight years, restoring Paramount's reputation for commercial success with The Odd Couple (Gene Saks, 1968), Rosemary's Baby (Roman Polanski, 1968), Love Story (Arthur Hiller, 1970), and The Godfather (Francis Coppola, 1972) and its sequels.

Evans abandoned his position as head of production in 1974. By 1976, a new, television-trained team was in place headed by Barry Diller and his associates, Michael Eisner, Jeffrey Katzenberg, Dawn Steel and Don Simpson, who would each go on and head up major movie studios of their own later in their careers. The Paramount specialty was now simpler. ‘High concept’ pictures such as Saturday Night Fever (John Badham, 1977) and Grease (Randall Kleisner, 1978) hit all over the world, and Apocalypse Now (Francis Coppola, 1979) was also a huge hit.

Paramount's successful run of pictures extended into the 1980s and 1990s, generating hits like An Officer and a Gentleman (Taylor Hackford, 1982), Flashdance (Adrian Lyne, 1983), Terms of Endearment (James L. Brooks, 1983), Top Gun (Tony Scott, 1986) with Tom Cruise, and the Friday the 13th slasher series. Paramount teamed up with Lucasfilm to create the Indiana Jones franchise. During this period, responsibility for running the studio passed from Eisner and Katzenberg to Frank Mancuso, Sr. (1984) and Ned Tanen (1984) to Stanley R. Jaffe (1991) and Sherry Lansing (1992).

In 1994 Paramount was acquired by Viacom Inc. Titanic (James Cameron, 1997), made jointly with 20th Century Fox, tied the record for most Academy Awards and was the first film to earn more than $1 billion at the box office. More recent Paramount’s hits include both the Iron Man and Star Trek series, and The Wolf of Wall Street (Martin Scorsese, 2013) starring Leonardo DiCaprio.

Paramount is the last major film studio located in Hollywood proper. For a time the semi-industrial neighbourhood around Paramount was in decline, but has now come back. The recently refurbished studio has come to symbolize Hollywood for many visitors, and its studio tour is a popular attraction. The distinctively pyramidal Paramount mountain has been the company's logo since its inception and is the oldest surviving Hollywood film logo. In the sound era, the logo was accompanied by a fanfare called Paramount on Parade after the film of the same name, released in 1930. Legend has it that the mountain is based on a doodle made by W. W. Hodkinson during a meeting with Adolph Zukor. It is said to be based on the memories of his childhood in Utah.

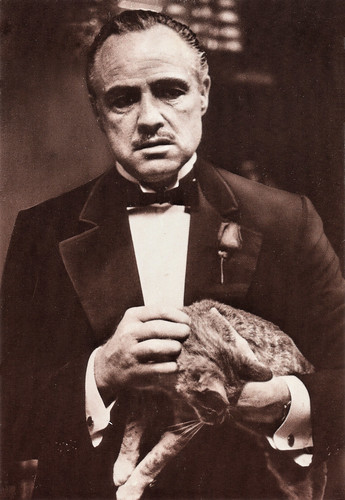

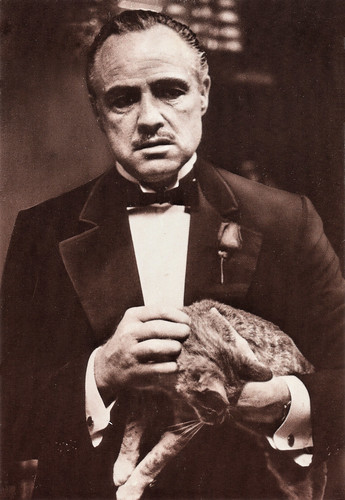

Marlon Brando. American postcard by Classico San Francisco, no. 136-183. Photo: The Ludlow Collection. Publicity still for The Godfather (Francis Ford Coppola, 1972).

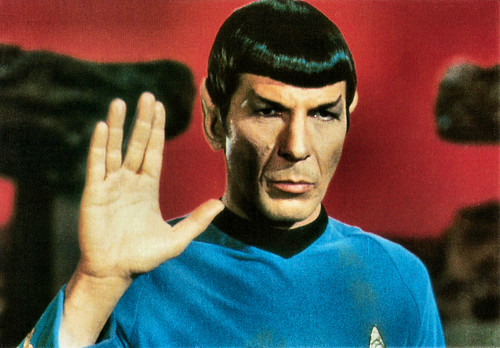

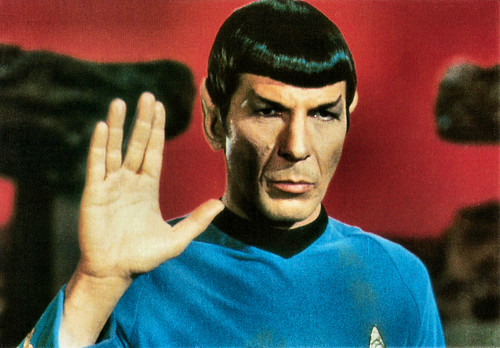

Leonard Nimoy as Spock in Star Trek. American postcard by Classico, San Francisco, no. 105-117. Photo: Paramount Pictures, 1991.

Kate Winslet and Leonardo DiCaprio. Vintage postcard. Photo: publicity still for Titanic (James Cameron, 1997).

Sources: Encyclopaedia Britannica, Film Reference, Wikipedia and IMDb.

Rudolph Valentino. German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 4685/1, 1929-1930. Photo: Paramount. Publicity still for Blood and Sand (Fred Niblo, 1922).

Gary Cooper. German postcard by Ross-Verlag, no. 5751/1, 1930-1931. Photo: Paramount. Publicity still for Morocco (Josef von Sternberg, 1930). Cooper was mistakenly credited as 'Garry Cooper'.

Marlene Dietrich. German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 6673/2, 1931-1932. Photo: Don English / Paramount. Publicity still for Shanghai Express (Josef von Sternberg, 1932).

Veronica Lake. Big Belgian card by Chocolaterie Clovis, Pepinster. Photo: George Hurrell / Paramount. Publicity still for This Gun for Hire (Frank Tuttle, 1942).

Charlton Heston. Dutch postcard by Gebr. Spanjersberg N.V., Rotterdam, no. 5183. Photo: Paramount. Publicity still for The Ten Commandments (Cecil B. DeMille, 1956) with Heston as Moses. Moses' robe was hand-woven by Dorothea Hulse, one of the world's finest weavers. She also created costumes for The Robe, as well as textiles and costume fabrics for Samson and Delilah, David and Bathsheba, and others.

Famous Players in Famous Plays

Famous Players was created in 1912 by Adolph Zukor, a Hungarian immigrant who started in the penny arcade and nickelodeon business in New York in the early 1900s. Famous Players enjoyed early success producing and distributing multi-reel (feature-length) films and developing a star-driven market strategy.

With partners Daniel Frohman and Charles Frohman, Zukor planned to make films which appealed to the middle class by featuring the leading theatrical players of the time ('Famous Players in Famous Plays'). By mid-1913, Famous Players had completed five films. Its first film was Les Amours de la reine Élisabeth/Queen Elizabeth (Henri Desfontaines, Louis Mercanton, 1912) which starred Sarah Bernhardt.

Meanwhile, three young filmmaking entrepreneurs, Jesse Lasky, Samuel Goldfish (later Goldwyn), and Cecil B. DeMille, launched a production company in Hollywood in 1913, Jesse L. Lasky Feature Play Company. They scored a major hit in 1914 with their first feature production, The Squaw Man (Oscar Apfel, Cecil B. DeMille, 1914).

That same year, as the movies were rapidly becoming a major entertainment enterprise, W. W. Hodkinson formed a nationwide distribution company, Paramount Pictures, to release the films produced by Famous Players, Lasky, and others. Paramount was the first successful nationwide distributor. Until this time, films were sold on a state-wide or regional basis which had proved costly to film producers. Also, Famous Players and Lasky were privately owned while Paramount was a corporation.

Zukor and Lasky bought Hodkinson out of Paramount, and merged the three companies into one. The new company Lasky and Zukor founded, Famous Players-Lasky Corporation, grew quickly, with Lasky and his partners Goldwyn and DeMille running the production side, Hiram Abrams in charge of distribution, and Zukor making great plans. With only the exhibitor-owned First National as a rival, Famous Players-Lasky and its Paramount Pictures soon dominated the business.

Because Zukor believed in stars, he signed and developed many of the leading early stars, including Mary Pickford, Pauline Frederick, William S. Hart, Douglas Fairbanks, Fatty Arbuckle, Gloria Swanson, and Wallace Reid. With so many important players, Paramount was able to introduce ‘block booking’, which meant that an exhibitor who wanted a particular star's films had to buy a year's worth of other Paramount productions. It was this system that gave Paramount a leading position in the 1920s and 1930s, but which led the government to pursue it on antitrust grounds for more than twenty years.

The studio produced scores of top hits, ranging from Rudolph Valentino vehicles like The Sheik (George Melford, 1921) and Blood and Sand (Fred Niblo, 1922) to Western epics like The Covered Wagon (James Cruze, 1923) and the DeMille spectacles The Ten Commandments (1923) and The King of Kings (1927).

Pola Negri. German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 939/5, 1925-1926. Photo: Paramount-Film. Publicity still for The Cheat (George Fitzmaurice, 1923).

Italian postcard by Casa Editrice Ballerini & Fratini, Firenze (B.F.F.), no. 446. Photo: Paramount. Publicity still for Why Worry (Fred C. Newmeyer, Sam Taylor, 1923) with Harold Lloyd and Jobyna Ralston.

Gloria Swanson. German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 1488/3, 1927-1928. Photo: Paramount / Parafumet. Publicity still for Stage Struck (Allan Dwan, 1925).

Clara Bow. German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 3510/1, 1928-1929. Photo: Paramount.

Charles Rogers, Nancy Carroll, and Jean Hersholt. German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 111/1. Photo: Paramount. Publicity still for Abie's Irish Rose (Victor Fleming, 1928), which was based on a popular Broadway play.

A Movie Factory

In 1926, Adolph Zukor hired independent producer B. P. Schulberg, an unerring eye for new talent, to run the film studio. Paramount was one of the first Hollywood studios to release what were known at that time as ‘talkies’, and in 1929, released their first musical, Innocents of Paris (Richard Wallace, 1929). Maurice Chevalier starred and sung the most famous song from the film, Louise.

Eventually, Zukor shed most of his early partners. In 1935, Paramount went bankrupt. Zukor was bumped up to chairman of the board. In this role, he reorganised the company as Paramount Pictures, Inc. and was able to successfully bring the studio out of bankruptcy.

Paramount continued to emphasize stars; in the 1920s there were Swanson, Valentino, and Clara Bow. By the 1930s, talkies brought in a range of powerful new draws: Miriam Hopkins, Marlene Dietrich, Mae West, W.C. Fields, Jeanette MacDonald, Claudette Colbert, Dorothy Lamour, Carole Lombard, Bing Crosby, band leader Shep Fields, famous Argentine tango singer Carlos Gardel, and Gary Cooper among them.

Like the other majors, Paramount's house style was geared to a range of star genre formulas; but the studio was unique in that these generally were handled not by unit producers but by specific directors who were granted considerable creative autonomy and control. Examples are Josef von Sternberg's highly stylized Dietrich melodramas like Morocco (1930), Shanghai Express (1932) and Blonde Venus (1932), and Ernst Lubitsch's distinctive musical operettas with Jeanette MacDonald such as The Love Parade (1929) and One Hour With You (1932).

While the key elements in these star-genre units were director and star, other filmmakers were crucial as well: writer Jules Furthman and cinematographer Lee Garmes on the Dietrich films, for example, and the production design by Hans Dreier on all of the films directed by both Lubitsch and von Sternberg during this period.

In this period Paramount can truly be described as a movie factory, turning out sixty to seventy pictures a year. Such were the benefits of having a huge theatre chain to fill, and of block booking to persuade other chains to go along. The studio's invested heavily in comedy during the early sound era, best typified perhaps by its run of the Marx Brothers comedies: The Cocoanuts (Robert Florey, Joseph Santley, 1929), Animal Crackers (Victor Heerman, 1930), Monkey Business (Norman Z. McLeod, 1931), Horse Feathers (Norman Z. McLeod, 1932), and Duck Soup (Leo McCarey, 1933). The first two films were shot at Paramount's Astoria, New York, studio.

W. C. Fields, George Burns & Gracie Allen, and Jack Oakie also contributed to this comedy trend, whose roots ran deeply into American vaudeville. In 1933, Mae West would add greatly to Paramount's success with her suggestive movies She Done Him Wrong (Lowell Sherman, 1933) and I'm No Angel (Wesley Ruggles, 1933). However, the sex appeal West gave in these movies would also lead to the enforcement of the Production Code, as the newly formed organization the Catholic Legion of Decency threatened a boycott if it was not enforced.

Influential comedy directors were Leo McCarey with Belle of the Nineties (1934) and Ruggles of Red Gap (1935) with Charles Laughton, and, Mitchell Leisen with Easy Living (1937) with Jean Arthur and Ray Milland, and Midnight (1939) with Claudette Colbert.

W.C. Fields and Chester Conklin. Dutch card. Photo: Paramount. Publicity still for Fools for Luck (Charles Reisner, 1928).

Jeanette MacDonald. French postcard by Cinémagazine-Edition, no. 796. Photo: Paramount. Publicity still for The Love Parade (Ernst Lubitsch, 1929).

Maurice Chevalier. German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 531. Photo: Paramount.

Charles 'Buddy' Rogers and Nancy Carroll. German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 5547/1, 1930-1931. Photo: Paramount. Publicity still for Follow Thru (Lloyd Corrigan, Laurence Schwab, 1930).

Claudette Colbert and Henry Wilcoxon. French postcard by A.N., Paris, no. 962. Photo: Paramount. Publicity still for Cleopatra (Cecil B. DeMille, 1934).

The end of the classic Hollywood studio system

In 1940, Paramount agreed to a government-instituted consent decree: block booking and ‘pre-selling’ (the practice of collecting up-front money for films not yet in production) would end. Immediately, Paramount cut back on production, from 71 films to a more modest 19 annually in the war years.

Still, with more new stars like Bob Hope, Alan Ladd, Veronica Lake, Paulette Goddard, and Betty Hutton, and with war-time attendance at astronomical numbers, Paramount and the other integrated studio-theatre combines made more money than ever.

At this, the Federal Trade Commission and the Justice Department decided to reopen their case against the five integrated studios. This led to the Supreme Court decision United States v. Paramount Pictures, Inc. (1948) holding that movie studios could not also own movie theatre chains. This decision broke up Adolph Zukor's creation, with the theatre chain being split into a new company, United Paramount Theatres, and effectively brought an end to the classic Hollywood studio system.

With the separation of production and exhibition forced by the U.S. Supreme Court, Paramount Pictures Inc. was split in two. Paramount Pictures Corporation was formed to be the production distribution company, with the 1,500-screen theatre chain handed to the new United Paramount Theatres on December 31, 1949. Leonard Goldenson, who had headed the chain since 1938, remained as the new company's president.

Despite such setbacks, Paramount had a number of successes in the 1940s and 1950s, notably the satirical comedies of writer-director Preston Sturges such as The Lady Eve (1941) and Going My Way (1944), the cynical dramas and comedies of writer-director Billy Wilder like Double Indemnity (1944) and Sunset Boulevard (1950), the Road to-comedies of Bob Hope, Bing Crosby, and Dorothy Lamour the Western Shane (1953), and Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window (1954) with James Stewart and Grace Kelly.

With the loss of the theatre chain, Paramount Pictures went into a decline, cutting studio-backed production, releasing its contract players, and making production deals with independents. By the mid-1950s, all the great names were gone. Only Cecil B. DeMille, associated with Paramount since 1913, kept making pictures in the grand old style. Despite Paramount's losses, DeMille would, however, give the studio some relief and create his most successful film at Paramount, a remake of his 1923 film The Ten Commandments (1956), starring Charlton Heston and Yul Brynner. DeMille died in 1959.

Like some other studios, Paramount saw little value in its film library, and sold 764 of its pre-1948 films.

Charles Laughton. Vintage postcard. Photo: Paramount. Publicity still for Ruggles of Red Gap (1935).

Victor Mature. French postcard by Editions P.I., Paris, no. 358, 1954. Photo: Paramount Pictures Inc.. Publicity still for Samson and Delilah (Cecil B. DeMille, 1949).

Dorothy Lamour. French postcard by Viny, no. 13. Photo: Paramount.

Grace Kelly. French postcard by Editions P.I., Paris, no. 584, Photo: Paramount, 1954.

Yul Brynner. French postcard by Editions P.I., Paris, no. 831. Photo: Paramount. Publicity still for The Ten Commandments (Cecil B. DeMille, 1956). For his pursuit of the Israelites, Brynner in his role as Rameses II wears the blue Khepresh helmet-crown, which the pharaohs wore for battle.

High Concept Pictures

By the early 1960s, Paramount's future was doubtful. The high-risk movie business was wobbly; the theatre chain was long gone; investments in television came to nothing; and the Golden Age of Hollywood had just ended. Films of this period include Psycho (Alfred Hitchcock, 1960) and Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961).

In 1966, a sinking Paramount was sold to Charles Bluhdorn's industrial conglomerate, Gulf + Western Industries Corporation. Bluhdorn immediately put his stamp on the studio, installing a virtually unknown producer named Robert Evans as head of production. Despite some rough times, Evans held the job for eight years, restoring Paramount's reputation for commercial success with The Odd Couple (Gene Saks, 1968), Rosemary's Baby (Roman Polanski, 1968), Love Story (Arthur Hiller, 1970), and The Godfather (Francis Coppola, 1972) and its sequels.

Evans abandoned his position as head of production in 1974. By 1976, a new, television-trained team was in place headed by Barry Diller and his associates, Michael Eisner, Jeffrey Katzenberg, Dawn Steel and Don Simpson, who would each go on and head up major movie studios of their own later in their careers. The Paramount specialty was now simpler. ‘High concept’ pictures such as Saturday Night Fever (John Badham, 1977) and Grease (Randall Kleisner, 1978) hit all over the world, and Apocalypse Now (Francis Coppola, 1979) was also a huge hit.

Paramount's successful run of pictures extended into the 1980s and 1990s, generating hits like An Officer and a Gentleman (Taylor Hackford, 1982), Flashdance (Adrian Lyne, 1983), Terms of Endearment (James L. Brooks, 1983), Top Gun (Tony Scott, 1986) with Tom Cruise, and the Friday the 13th slasher series. Paramount teamed up with Lucasfilm to create the Indiana Jones franchise. During this period, responsibility for running the studio passed from Eisner and Katzenberg to Frank Mancuso, Sr. (1984) and Ned Tanen (1984) to Stanley R. Jaffe (1991) and Sherry Lansing (1992).

In 1994 Paramount was acquired by Viacom Inc. Titanic (James Cameron, 1997), made jointly with 20th Century Fox, tied the record for most Academy Awards and was the first film to earn more than $1 billion at the box office. More recent Paramount’s hits include both the Iron Man and Star Trek series, and The Wolf of Wall Street (Martin Scorsese, 2013) starring Leonardo DiCaprio.

Paramount is the last major film studio located in Hollywood proper. For a time the semi-industrial neighbourhood around Paramount was in decline, but has now come back. The recently refurbished studio has come to symbolize Hollywood for many visitors, and its studio tour is a popular attraction. The distinctively pyramidal Paramount mountain has been the company's logo since its inception and is the oldest surviving Hollywood film logo. In the sound era, the logo was accompanied by a fanfare called Paramount on Parade after the film of the same name, released in 1930. Legend has it that the mountain is based on a doodle made by W. W. Hodkinson during a meeting with Adolph Zukor. It is said to be based on the memories of his childhood in Utah.

Marlon Brando. American postcard by Classico San Francisco, no. 136-183. Photo: The Ludlow Collection. Publicity still for The Godfather (Francis Ford Coppola, 1972).

Leonard Nimoy as Spock in Star Trek. American postcard by Classico, San Francisco, no. 105-117. Photo: Paramount Pictures, 1991.

Kate Winslet and Leonardo DiCaprio. Vintage postcard. Photo: publicity still for Titanic (James Cameron, 1997).

Sources: Encyclopaedia Britannica, Film Reference, Wikipedia and IMDb.

No comments:

Post a Comment