RKO Pictures was, in its original incarnation as RKO Radio Pictures Inc., one of the Big Five studios of Hollywood's Golden Age. It was the last of the major studios to be created and the first (and only) studio to expire. Much of its 25 years’ existence, Radio-Keith-Orpheum spent struggling for financial stability, but despite this it produced many classic films including King Kong (1933), Bringing Up Baby (1938), Citizen Kane (1941), and The Best Years of Our Lives (1946). RKO has long been renowned for its cycle of musicals starring Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers in the mid- to late 1930s. Actors Katharine Hepburn and, later, Robert Mitchum had their first major successes at the studio. Cary Grant was a mainstay for years. The work of producer Val Lewton's low-budget horror unit and RKO's many ventures into Film Noir have been acclaimed by film critics and historians. RKO was also responsible for such co-productions as It's a Wonderful Life and Notorious, and from 1937 to the mid-50s, it distributed many celebrated films by Walt Disney. In 1948, monomaniacal Howard Hughes took over RKO, and after years of chaos and decline under his control, he sold off the studio's assets—both its films and its production facilities—to the burgeoning television industry. The original RKO Pictures ceased production in 1957 and was dissolved two years later.

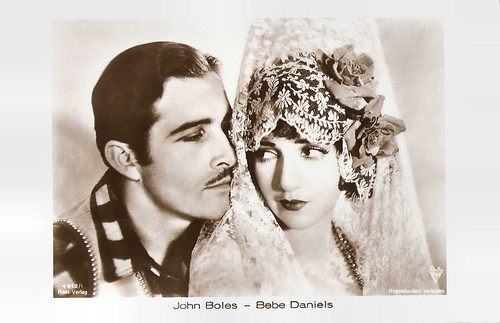

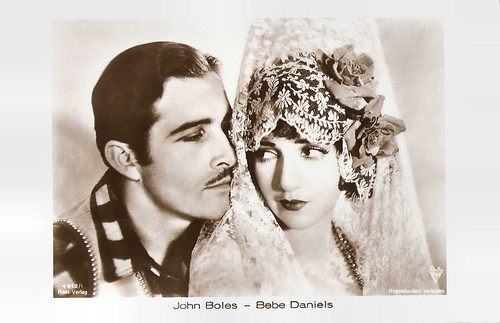

Bebe Daniels and John Boles. German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 4812/1, 1929-1930. Photo: Radio Pictures (RKO). Publicity still for Rio Rita (Luther Reed, 1929).

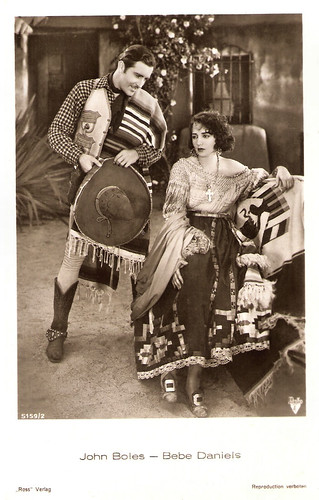

Bebe Daniels and John Boles. German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 51592, 1930-1931. Photo: Radio Pictures (RKO). Publicity still for Rio Rita (Luther Reed, 1929).

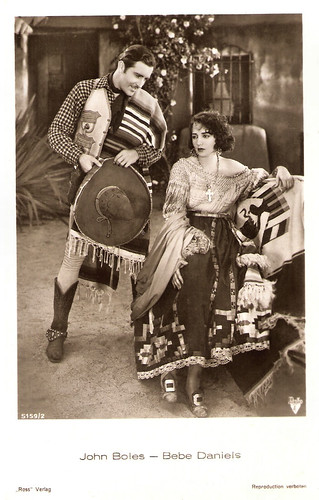

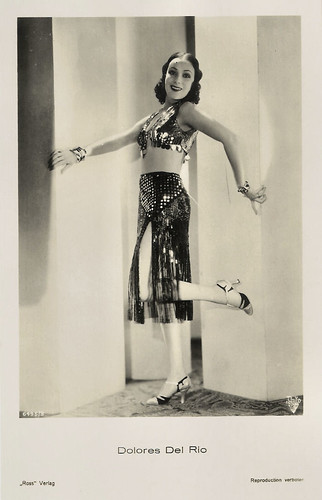

Dolores del Rio. German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 6495/3, 1931-1932. Photo: Radio Pictures (RKO).

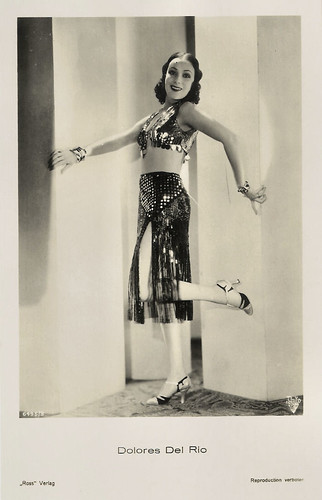

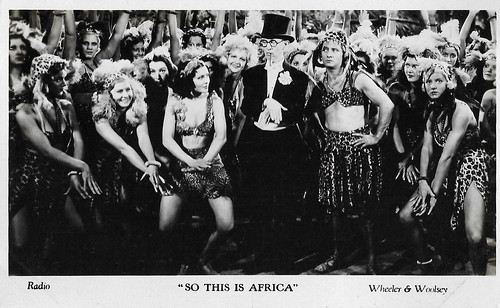

Bert Wheeler and Robert Woolsey. British postcard in the Filmshots series by Film Weekly. Photo: Radio. Publicity still for So This Is Africa (Edward F. Cline, 1933).

Katharine Hepburn. British Real Photograph postcard, no. 40.A. Photo: Radio Pictures.

In 1928, RKO Radio Pictures Inc. was formed after the Keith-Albee-Orpheum (KAO) theatre chain and Joseph P. Kennedy's Film Booking Offices of America (FBO) studio were brought together under the control of the Radio Corporation of America (RCA). RCA chief David Sarnoff engineered the merger to create a market for the company's sound-on-film technology, RCA Photophone.

RKO (also written as R.K.O.) began production at the small facility FBO shared with Pathé in New York City while the main FBO studio in Hollywood was technologically refitted. The new company's two initial releases were musicals: Syncopation (Bert Glennon, 1929), which had been produced by FBO, and Street Girl (Wesley Ruggles, 1930), billed as RKO's first ‘official’ production and its first to be shot in Hollywood.

A few non-singing pictures followed, but the studio's first major hit was again a musical. RKO spent heavily on the lavish Rio Rita (Luther Reed, 1930), starring Bebe Daniels and the comedy team of Wheeler & Woolsey and including a number of Technicolor sequences. Opening in September to rave reviews, it was named one of the ten best pictures of the year by Film Daily.

RKO released a limited slate of twelve features in its first year; in 1930, that figure more than doubled to twenty-nine. Encouraged by Rio Rita's success, RKO produced several costly musicals incorporating Technicolor sequences, among them Dixiana (1930) with Bebe Daniels, and Hit the Deck (1930) with Jack Oakie, both again scripted and directed by Luther Reed.

Following the example of the other major studios, RKO had planned to create its own musical revue, Radio Revels. Promoted as the studio's most extravagant production to date, it was to be photographed entirely in Technicolor. The project was abandoned, however, as the public's taste for musicals temporarily subsided. From a total of more than sixty Hollywood musicals in 1929 and over eighty the following year, the number dropped to eleven in 1931.

Even as the U.S. economy foundered, RKO had gone on a spending spree, buying up theatre after theatre to add to its exhibition chain. In October 1930, the company purchased a 50 percent stake in the New York Van Beuren studio, which specialised in cartoons and live shorts. RKO's production schedule soon surpassed forty features a year, released under the names Radio Pictures and, for a short time after the 1931 merger, RKO Pathé. The Western Cimarron (Wesley Ruggles,1931), based on the novel by Edna Ferber and starring Richard Dix, would become the only RKO production to win the Academy Award for Best Picture. Nonetheless, having cost a profligate $1.4 million to make, it was a money-loser on original domestic release.

The most popular RKO star of this pre-Code era was Irene Dunne, who made her debut as the lead in the musical Leathernecking (Edward F. Cline, 1930) and was a headliner at the studio for the entire decade. Other major performers included Joel McCrea, Ricardo Cortez, Dolores del Rio, and Mary Astor. Richard Dix, Oscar-nominated for his lead performance in Cimarron, would serve as RKO's standby B-movie star until the early 1940s.The comedy team of Bert Wheeler and Robert Woolsey, often wrangling over ingenue Dorothy Lee, was a bankable mainstay for years.

RKO's product was largely regarded as mediocre, so in October 1931 the studio hired twenty-nine-year-old David O. Selznick as production chief. In addition to implementing rigorous cost-control measures, Selznick championed the unit production system, which gave the producers of individual films much greater independence than they had under the prevailing central producer system. Wikipedia cites Selznick: "Under the factory system of production you rob the director of his individualism and this being a creative industry that is harmful to the quality of the product made."

To make films under the new system, Selznick recruited prize behind-the-camera personnel, such as director George Cukor and producer/director Merian C. Cooper, and gave 26-years-old producer Pandro S. Berman increasingly important projects. Selznick discovered and signed a young actress who would quickly become one of the studio's biggest stars, Katharine Hepburn. John Barrymore was also enlisted for a few memorable performances.

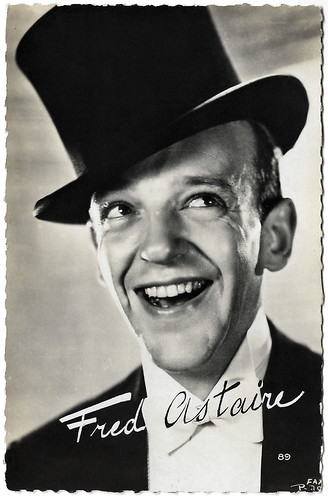

From September 1932 on, print advertising for the company's features displayed the revised name RKO Radio Pictures. Selznick spent a mere fifteen months as RKO production chief, resigning over a dispute with new corporate president Merlin Aylesworth concerning creative control. One of his last acts at RKO was to approve a screen test for a thirty-three-year-old, balding Broadway song-and-dance man named Fred Astaire.

Selznick's tenure was masterful: In 1931, before he arrived, the studio had produced forty-two features for $16 million in total budgets. In 1932, under Selznick, forty-one features were made for $10.2 million, with clear improvement in quality and popularity. He backed several major successes, including A Bill of Divorcement (George Cukor, 1932), Katharine Hepburn's debut, and the monumental monster adventure King Kong (Merian C. Cooper, Ernest B. Schoedsack, 1933).

Still, the shaky finances and excesses that marked the company's pre-Selznick days had not left RKO in shape to withstand the Depression. The studio sank into receivership in early 1933, from which it did not emerge until 1940. Cooper took over as production head after Selznick's departure and oversaw two hits starring Hepburn: Morning Glory (Lowell Sherman, 1933), for which she won her first Oscar, and Little Women (George Cukor, 1933), one of the studio’s biggest box-office successes of the decade.

Ginger Rogers had already made several minor films for RKO when Cooper signed her to a seven-year contract and cast her in the big-budget musical Flying Down to Rio (Thornton Freeland, 1933). Rogers was paired with Astaire, making his film debut. Billed fourth and fifth respectively, the picture turned them into stars. Hermes Pan, assistant to the film's dance director, would become one of Hollywood's leading choreographers through his subsequent work with Astaire.

Along with Columbia Pictures, RKO became one of the primary homes of the screwball comedy. William A. Seiter directed the studio's first significant contribution to the genre, The Richest Girl in the World (1934). The drama Of Human Bondage (John Cromwell, 1934), was Bette Davis's first great success. George Stevens's Alice Adams (1935) and John Ford's The Informer (1935) were each nominated for the 1935 Best Picture Oscar—the Best Director statuette won by Ford was the only one ever given for an RKO production. The Informer's star, Victor McLaglen, also took home an Academy Award; he would appear in a dozen films for the studio over a span of two decades.

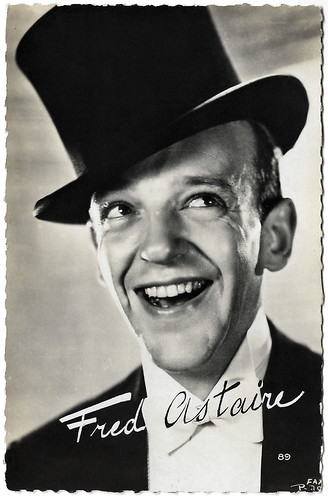

Fred Astaire. French postcard by Editions et Publications Cinematographiques, no. 89.

Bette Davis. Belgian collectors card by Chocolaterie Clovis, Pepinster. Collection: Amit Benyovits.

Victor McLaglen. French postcard by Ed. Chantal, Paris, no. 602. Photo: RKO.

Cary Grant. British postcard in the Picturegoer Series, London, no. W 609. Photo: R.K.O. Radio.

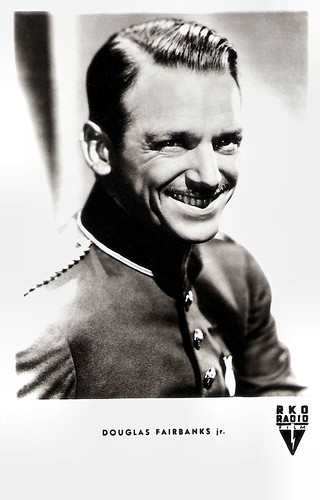

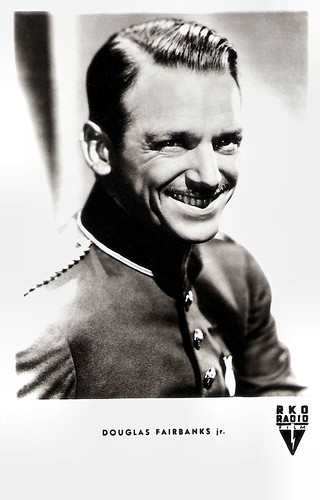

Douglas Fairbanks Jr. German postcard by Netter's Star Verlag, Berlin. Photo: RKO Radio Film. Publicity still for Gunga Din (George Stevens, 1939).

Lacking the financial resources of industry leaders MGM, Paramount, and Fox, RKO turned out many pictures during the era that made up for it with high style in an Art Deco mode, exemplified by such Astaire–Rogers musicals as The Gay Divorcee (Mark Sandrich, 1934), their first pairing as leads, and Top Hat (Mark Sandrich, 1935). One of the figures most responsible for that style was another Selznick recruit: Van Nest Polglase, chief of RKO's highly regarded design department for almost a decade.

In, 1935, RKO premiered the first feature film shot entirely in advanced three-strip Technicolor, Becky Sharp (Rouben Mamoulian, 1935). Though judged by critics a failure as drama, Becky Sharp was widely lauded for its visual brilliance and technical expertise. In 1935, Cary Grant joined the studio's roster. Grant was a trendsetter, one of the first leading men of the sound era to work extensively as a freelancer, under nonexclusive studio deals, while his star was still on the rise. Ann Sothern starred in seven RKO films between 1935 and 1937, paired five times with Gene Raymond.

Walt Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) was the highest grossing production in the period between The Birth of a Nation (David Wark Griffith, 1915) and Gone with the Wind (Victor Fleming, 1939). While the Disney association was beneficial, RKO's own product was widely seen as declining in quality. Then, Pandro S. Berman accepted the position of production chief on a noninterim basis. His brief tenure resulted in some of the most notable films in studio history, including the adventure film Gunga Din (George Stevens, 1939), with Cary Grant and Victor McLaglen; Love Affair (Leo McCarey, 1939), starring Irene Dunne and Charles Boyer; and The Hunchback of Notre Dame (William Dieterle, 1939). Charles Laughton, who played Quasimodo in the latter, returned periodically to the studio, headlining six more RKO features. For Maureen O'Hara, who made her American screen debut in the film, it was the first of ten pictures she would make for RKO through 1952.

After co-starring with Ginger Rogers for the eighth time in The Story of Vernon and Irene Castle (H.C. Potter, 1939), Fred Astaire departed the studio. The Wheeler and Woolsey comedy series ended in 1937 when Woolsey became ill and died the following year. B-Western star George O'Brien made eighteen RKO pictures, sixteen between 1938 and 1940. With The Saint in New York (Ben Holmes, 1938), RKO successfully launched a B-detective series featuring the character Simon Templar that would run through 1943. The studio soon had another new B-comedy star in Lupe Vélez: The Girl from Mexico (Leslie Goodwins, 1939) was followed by seven frantic instalments of the Mexican Spitfire series, all featuring Leon Errol, between 1940 and 1943.

Pandro S. Berman departed RKO in December 1939 after policy clashes with studio president George J. Schaefer. Schaefer was keen on signing up independent producers whose films RKO would distribute. In 1941, the studio landed one of the most prestigious independents in Hollywood, Samuel Goldwyn's productions. The first two Goldwyn pictures released by the studio were highly successful: The Little Foxes (William Wyler, 1941) starring Bette Davis, garnered four Oscar nominations, while Ball of Fire (Howard Hawks, 1941) brought Barbara Stanwyck a hit under the RKO banner.

David O. Selznick loaned out his leading contracted director for two RKO pictures in 1941: Alfred Hitchcock's comedy Mr. and Mrs. Smith (1941) with Carole Lombard, was a modest success and the thriller Suspicion (1941) with Joan Fontaine and Cary Grant, a more substantial one, with an Oscar-winning turn by Joan Fontaine.

That May, having granted twenty-five-year-old star and director Orson Welles virtually complete creative control over the film, RKO released Citizen Kane (1941). While it opened to strong reviews and would go on to be hailed as one of the greatest movies ever made, it lost money at the time and brought down the wrath of the Hearst newspaper chain on RKO. The next year saw the commercial failure of Welles's The Magnificent Ambersons (Orson Welles, 1942)and the expensive embarrassment of his aborted documentary It's All True. The three Welles productions combined to drain $2 million from the RKO coffers, major money for a corporation that had reported an overall deficit of $1 million in 1940 and a nominal profit of a bit more than $500,000 in 1941.

Many of RKO's other artistically ambitious pictures were also dying at the box office and it was losing its last exclusive deal with a major star as well. Ginger Rogers, after winning an Oscar in 1941 for her performance in the previous year's Kitty Foyle (Sam Wood, 1940), held out for a freelance contract like Grant's. Schaefer resigned and departed a weakened and troubled studio, but RKO was about to turn the corner. Propelled by the box-office boom of World War II and guided by new management, RKO would make a strong comeback over the next half-decade.

With Schaefer gone, Charles Koerner did the job and brought the studio much-needed stability until his death in February 1946. In June 1944, RKO created a television production subsidiary, RKO Television Corporation, to provide content for the new medium. RKO became the first major studio to produce for television with Talk Fast, Mister, a one-hour drama filmed at RKO-Pathé studios in New York and broadcast by the DuMont network's New York station, WABD, on 18 December 1944. Koerner sought to increase its output of handsomely budgeted, star-driven features. However, the studio's only remaining major stars were Cary Grant, whose services were shared with Columbia Pictures, and Maureen O'Hara, shared with Twentieth Century-Fox.

So RKO arranged with the other studios to loan out their biggest names or signed one of the growing number of freelance performers to short-term, ‘pay or play’ deals. John Wayne appeared in the comedy A Lady Takes a Chance (William A. Seiter, 1943) while on loan from Republic Pictures. He was soon working regularly with RKO, making nine more films for the studio. Gary Cooper appeared in RKO releases produced by Goldwyn and, later, the start-up International Pictures, and Claudette Colbert starred in a number of RKO co-productions.

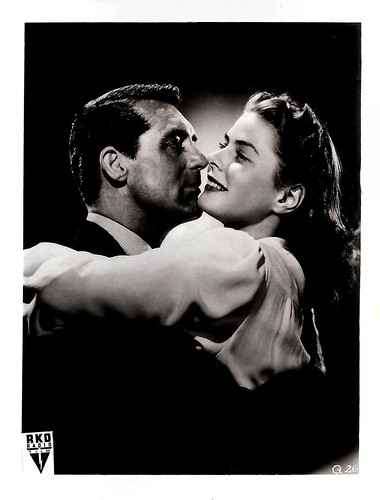

Ingrid Bergman, on loan out from Selznick, starred opposite Bing Crosby in The Bells of St. Mary's (Leo McCarey,1945). The top box-office film of the year, it turned a $3.7 million profit for RKO, the most in the company's history. Bergman returned in the co-productions Notorious (Alfred Hitchcock, 1946) and Stromboli (Roberto Rossellini, 1950), and in the independently produced Joan of Arc (Victor Fleming, 1948).

RKO and Orson Welles had an arm's-length reunion via The Stranger (Orson Welles, 1946), an independent production he starred in as well as directed. In December 1946, the studio released Frank Capra's It's a Wonderful Life (1946). While it would ultimately be recognised as one of the greatest films of Hollywood's Golden Age, at the time it lost more than half a million dollars for RKO. John Ford's The Fugitive (1947) and Fort Apache (1948), which appeared right before studio ownership changed hands again, were followed by She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949) and Wagon Master (1950); all four were co-productions between RKO and Argosy, the company run by Ford and RKO alumnus Merian C. Cooper.

Of the directors under long-term contract to RKO in the 1940s, the best known was Edward Dmytryk, who first came to notice with the remarkably profitable Hitler's Children (1943). Shot on a $205,000 budget, placing it in the bottom quartile of Big Five studio productions, it was one of the ten biggest Hollywood hits of the year. Another low-cost war-themed film directed by Dmytryk, Behind the Rising Sun (1943), released a few months later, was similarly profitable.

Much more than the other Big Five studios, RKO relied on B pictures to fill up its schedule. RKO had a history of making better profits with its run-of-the-mill and low-cost product than with its A movies. The studio's low-budget films offered training opportunities for new directors, as well, among them Mark Robson, Robert Wise, and Anthony Mann.

Robson and Wise received their first directing assignments with producer Val Lewton, whose specialised B-horror unit also included the more experienced director Jacques Tourneur. The Lewton unit's moody, atmospheric work — represented by films such as Cat People (Jacques Tourneur, 1942) with Simone Simon, I Walked with a Zombie (Jacques Tourneur, 1943), and The Body Snatcher (Robert Wise, 1945) — is now highly regarded. Johnny Weissmuller starred in six Tarzan pictures for RKO between 1943 and 1948 before being replaced by Lex Barker.

Film noir, to which lower budgets lent themselves, became something of a house style at the studio, indeed, the RKO B-Film Noir Stranger on the Third Floor (Boris Ingster, 1940) with Peter Lorre, is widely seen as initiating Noir's classic period. The studio's 1940s list of contract players was filled with Noir regulars: Robert Mitchum (who graduated to major star status) and Robert Ryan each made no fewer than ten film noirs for RKO. Gloria Grahame, Jane Greer, and Lawrence Tierney were also notable studio players in the field. Freelancer George Raft starred in two Noir hits: Johnny Angel (Edwin L. Marin, 1945) and Nocturne (1946). Tourneur, Mitchum, and Greer joined to make the A-budgeted Out of the Past (Edwin L. Marin, 1947), now considered one of the greatest of all Film Noirs. Nicholas Ray began his directing career with the Noir They Live by Night (1948), the first of a number of well-received films he made for RKO.

Charles Boyer and Irene Dunne. British postcard in the Film Partners Series, London, no. P 268. Photo: R.K.O. Radio. Publicity photo for Love Affair (1939, Leo McCarey).

Maureen O'Hara. Dutch postcard by J.S.A. Photo: M.P.E.

Orson Welles. French postcard by Editions du Globe, no. 143. Photo: Sam Lévin.

Claudette Colbert. Dutch postcard by S. & v. H., A. Photo: M.P.E.A.

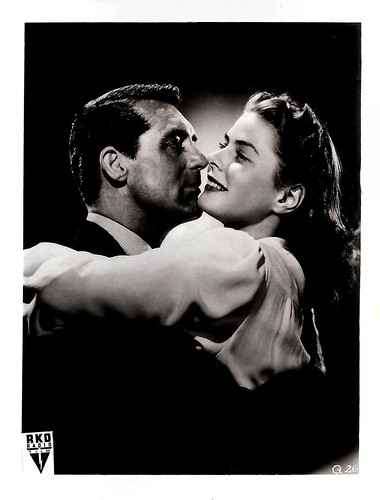

Cary Grant and Ingrid Bergman. German collectors card. Photo: RKO Radio Film. Publicity still for Notorious (Alfred Hitchcock, 1946).

RKO, and Hollywood as a whole, had its most profitable year ever in 1946. A Goldwyn production released by RKO, The Best Years of Our Lives (William Wyler, 1946), was the most successful Hollywood film of the decade. But the legal status of the industry's reigning business model was increasingly being called into doubt: the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Bigelow v. RKO that the company was liable for damages under antitrust statutes for having denied an independent movie house access to first run films—a common practice among all of the Big Five.

After Koerner's death, producer and Oscar-winning screenwriter Dore Schary took over his role. RKO appeared in good shape to build on its recent successes, but the year brought a number of unpleasant harbingers for all of Hollywood. The post-war attendance boom peaked sooner than expected and television emerged as a competitor for audience interest. Across the board, profits fell — a 27 percent drop for the Hollywood studios from 1946 to 1947.

The phenomenon that would become known as McCarthyism was building strength, and in October, the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) began hearings into Communism in the motion picture industry. Two of RKO's top talents, director Edward Dmytryk and producer Adrian Scott, refused to cooperate. As a consequence, they were fired by RKO per the terms of the Waldorf Statement, the major studios' pledge to "eliminate any subversives". Scott, Dmytryk, and eight others who also defied HUAC — dubbed the Hollywood Ten — were blacklisted across the industry. Ironically, the studio's major success of the year was Crossfire (Edward Dmytryk, 1947), a Scott–Dmytryk film.

For her performance in The Farmer's Daughter (H.C. Potter, 1947), a coproduction with Selznick's Vanguard Films, Loretta Young won the Best Actress Oscar the following March. It would turn out to be the last major Academy Award for an RKO picture. In May 1948, eccentric aviation tycoon and occasional movie producer Howard Hughes gained control of the company. During Hughes's tenure, RKO suffered its worst years since the early 1930s, as his capricious management style took a heavy toll. Production chief Schary quit almost immediately due to his new boss's interference and within weeks of taking over, Hughes had dismissed three-fourths of the work force. Production was virtually shut down for six months as the conservative Hughes shelved or cancelled several of the ‘message pictures’ that Schary had backed.

Once shooting picked up again, Hughes quickly became notorious for meddling in minute production matters, particularly the presentation of actresses he favoured. The production-distribution end of the RKO business, now deep in the red, would never make a profit again. Offscreen, Robert Mitchum's arrest and conviction for marijuana possession — he would serve two months in jail — was widely assumed to mean career death for RKO's most promising young star, but Hughes surprised the industry by announcing that his contract was not endangered.

Of much broader significance, Hughes decided to get the jump on his Big Five competitors by being the first to settle the federal government's antitrust suit against the major studios, which had won a crucial Supreme Court ruling in United States v. Paramount Pictures, Inc. Under the consent decree he signed, Hughes agreed to dissolve the old parent company, Radio-Keith-Orpheum Corp., and split RKO's production-distribution business and its exhibition chain into two entirely separate corporations — RKO Pictures Corp. and RKO Theatres Corp. — with the obligation to promptly sell off one or the other. While Hughes delayed the divorcement procedure until December 1950 and didn't actually sell his stock in the theatre company for another three years, his decision to acquiesce was one of the crucial steps in the collapse of classical Hollywood's studio system.

While Hughes's time at RKO was marked by dwindling production and a slew of expensive flops, the studio continued to turn out some well-received films under production chiefs Sid Rogell and Sam Bischoff, though both became fed up with Hughes's meddling and quit after less than two years. There were B Noirs such as The Window (Ted Tetzlaff, 1949), which turned into a hit, and The Set-Up (Robert Wise, 1949), starring Robert Ryan, which won the Critic's Prize at the Cannes Film Festival. The Thing from Another World (Christian Nyby, Howard Hawks, 1951), a science-fiction drama coproduced with Howard Hawks's Winchester Pictures, is a classic of the genre.

In 1952, RKO put out two films directed by Fritz Lang, Rancho Notorious and Clash by Night. The company also began a close working relationship with Ida Lupino. She starred in two suspense films with Robert Ryan — Nicholas Ray's On Dangerous Ground (1952) and Beware, My Lovely (Harry Horner, 1952), a coproduction between RKO and Ida Lupino's company, The Filmakers. Lupino was Hollywood's only female director during the period; of the five pictures The Filmakers made with RKO, Lupino directed three, including her now celebrated The Hitch-Hiker (Ida Lupino, 1953).

Exposing many filmgoers to Asian cinema for the first time, RKO distributed Akira Kurosawa's epochal Rashomon (1950) in the United States. The only smash hits released by RKO in the 1950s came out during this period, but neither was an in-house production: Goldwyn's Hans Christian Andersen (Charles Vidor, 1952) with Danny Kaye, was followed by Walt Disney's Peter Pan (Clyde Geronimi a.o., 1953). Convinced that the studio was sinking, Walt Disney ended his arrangement with RKO and set up his own distribution firm, Buena Vista Pictures. Howard Hughes had to leave and the new owners of RKO became General Tire.

By 1956, RKO's classic films were playing widely on television, allowing many to see such masterpieces as Citizen Kane (Orson Welles, 1941) for the first time. The $15.2 million RKO made on the deal convinced the other major studios that their libraries held profit potential — a turning point in the way Hollywood did business with television. The new owners of RKO, General Tire, made an initial effort to revive the studio, hiring veteran producer William Dozier to head production. In the first half of 1956, the production facilities were as busy as they had been in a half-decade. RKO Teleradio Pictures released Fritz Lang's final two American films, While the City Sleeps (1956) and Beyond a Reasonable Doubt (1956), but years of mismanagement had driven away many directors, producers, and stars.

The studio was also saddled with the last of the inflated B-movies such as Pearl of the South Pacific (Allan Dwan, 1955) and The Conqueror (Dick Powell, 1956) that enchanted Hughes. The latter, starring John Wayne, was the biggest hit produced at the studio during the decade, but its $4.5 million in North American rentals did not come close to covering its $6 million cost. After a year and a half without a notable success, General Tire shut down production at RKO for good at the end of January 1957. The Hollywood facilities were sold later that year for $6.15 million to Desilu Productions, owned by Desi Arnaz and Lucille Ball.

After numerous corporate reorganisations, the firm continued under the name RKO General, Inc., owning and operating radio and television stations, theatres, and related enterprises. Most of the films released by RKO Pictures between 1929 and 1957 have an opening ident displaying the studio's famous trademark, the spinning globe and radio tower, nicknamed the 'Transmitter'. It was inspired by a two-hundred-foot tower built in Colorado for a giant electrical amplifier, or Tesla coil, created by inventor Nikola Tesla. The studio's closing ident, a triangle enclosing a thunderbolt, was also a well-known trademark.

Finally, we cite Wikipedia in turn citing scholar Richard B. Jewell: "The supreme irony of RKO's existence is that the studio earned a position of lasting importance in cinema history largely because of its extraordinarily unstable history. Since it was the weakling of Hollywood's 'majors,' RKO welcomed a diverse group of individualistic creators and provided them...with an extraordinary degree of freedom to express their artistic idiosyncrasies.... [I]t never became predictable and it never became a factory.”

Robert Mitchum. British postcard in the Picturegoer Series, London, no. W 758. Photo: R.K.O. Radio.

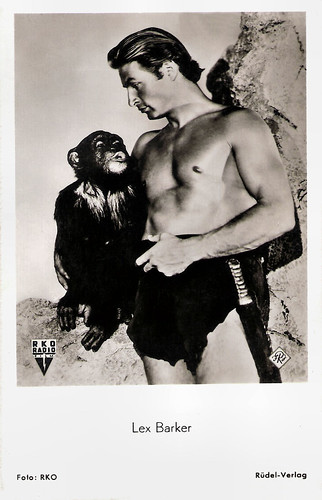

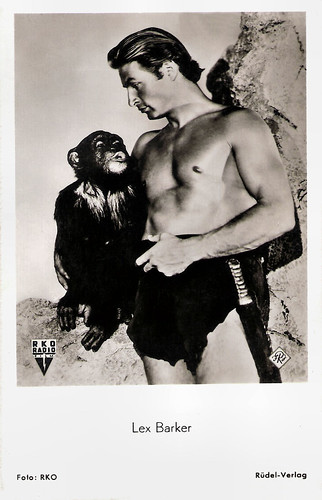

Lex Barker. German postcard by Rüdel-Verlag, Hamburg-Bergedorf, no. 449. Photo: Alex Kahle / RKO Radio Film. Publicity still for Tarzan's Magic Fountain (Lee Sholem, 1949).

Gloria Grahame. German postcard by Kunst und Bild, Berlin, no. A 791. Photo: RKO. Publicity still for Sudden Fear (David Miller, 1952).

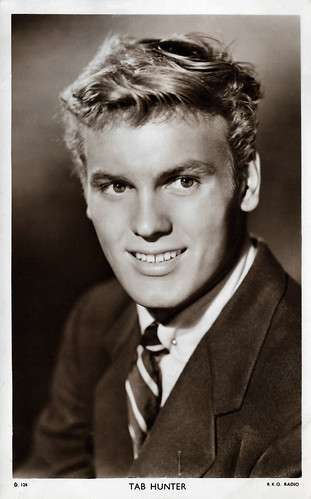

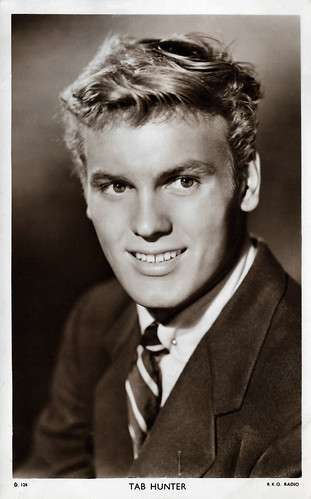

Tab Hunter. British postcard in the Picturegoer series, London, no. D 126. Photo: R.K.O. Radio.

Guy Madison. British postcard in the Picturegoer Series, London, no. W 815. Photo: R.K.O. Radio.

Sources: Encyclopaedia Britannica, Film Reference, Wikipedia and IMDb.

Bebe Daniels and John Boles. German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 4812/1, 1929-1930. Photo: Radio Pictures (RKO). Publicity still for Rio Rita (Luther Reed, 1929).

Bebe Daniels and John Boles. German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 51592, 1930-1931. Photo: Radio Pictures (RKO). Publicity still for Rio Rita (Luther Reed, 1929).

Dolores del Rio. German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 6495/3, 1931-1932. Photo: Radio Pictures (RKO).

Bert Wheeler and Robert Woolsey. British postcard in the Filmshots series by Film Weekly. Photo: Radio. Publicity still for So This Is Africa (Edward F. Cline, 1933).

Katharine Hepburn. British Real Photograph postcard, no. 40.A. Photo: Radio Pictures.

The masterful tenure of David O'Selznick

In 1928, RKO Radio Pictures Inc. was formed after the Keith-Albee-Orpheum (KAO) theatre chain and Joseph P. Kennedy's Film Booking Offices of America (FBO) studio were brought together under the control of the Radio Corporation of America (RCA). RCA chief David Sarnoff engineered the merger to create a market for the company's sound-on-film technology, RCA Photophone.

RKO (also written as R.K.O.) began production at the small facility FBO shared with Pathé in New York City while the main FBO studio in Hollywood was technologically refitted. The new company's two initial releases were musicals: Syncopation (Bert Glennon, 1929), which had been produced by FBO, and Street Girl (Wesley Ruggles, 1930), billed as RKO's first ‘official’ production and its first to be shot in Hollywood.

A few non-singing pictures followed, but the studio's first major hit was again a musical. RKO spent heavily on the lavish Rio Rita (Luther Reed, 1930), starring Bebe Daniels and the comedy team of Wheeler & Woolsey and including a number of Technicolor sequences. Opening in September to rave reviews, it was named one of the ten best pictures of the year by Film Daily.

RKO released a limited slate of twelve features in its first year; in 1930, that figure more than doubled to twenty-nine. Encouraged by Rio Rita's success, RKO produced several costly musicals incorporating Technicolor sequences, among them Dixiana (1930) with Bebe Daniels, and Hit the Deck (1930) with Jack Oakie, both again scripted and directed by Luther Reed.

Following the example of the other major studios, RKO had planned to create its own musical revue, Radio Revels. Promoted as the studio's most extravagant production to date, it was to be photographed entirely in Technicolor. The project was abandoned, however, as the public's taste for musicals temporarily subsided. From a total of more than sixty Hollywood musicals in 1929 and over eighty the following year, the number dropped to eleven in 1931.

Even as the U.S. economy foundered, RKO had gone on a spending spree, buying up theatre after theatre to add to its exhibition chain. In October 1930, the company purchased a 50 percent stake in the New York Van Beuren studio, which specialised in cartoons and live shorts. RKO's production schedule soon surpassed forty features a year, released under the names Radio Pictures and, for a short time after the 1931 merger, RKO Pathé. The Western Cimarron (Wesley Ruggles,1931), based on the novel by Edna Ferber and starring Richard Dix, would become the only RKO production to win the Academy Award for Best Picture. Nonetheless, having cost a profligate $1.4 million to make, it was a money-loser on original domestic release.

The most popular RKO star of this pre-Code era was Irene Dunne, who made her debut as the lead in the musical Leathernecking (Edward F. Cline, 1930) and was a headliner at the studio for the entire decade. Other major performers included Joel McCrea, Ricardo Cortez, Dolores del Rio, and Mary Astor. Richard Dix, Oscar-nominated for his lead performance in Cimarron, would serve as RKO's standby B-movie star until the early 1940s.The comedy team of Bert Wheeler and Robert Woolsey, often wrangling over ingenue Dorothy Lee, was a bankable mainstay for years.

RKO's product was largely regarded as mediocre, so in October 1931 the studio hired twenty-nine-year-old David O. Selznick as production chief. In addition to implementing rigorous cost-control measures, Selznick championed the unit production system, which gave the producers of individual films much greater independence than they had under the prevailing central producer system. Wikipedia cites Selznick: "Under the factory system of production you rob the director of his individualism and this being a creative industry that is harmful to the quality of the product made."

To make films under the new system, Selznick recruited prize behind-the-camera personnel, such as director George Cukor and producer/director Merian C. Cooper, and gave 26-years-old producer Pandro S. Berman increasingly important projects. Selznick discovered and signed a young actress who would quickly become one of the studio's biggest stars, Katharine Hepburn. John Barrymore was also enlisted for a few memorable performances.

From September 1932 on, print advertising for the company's features displayed the revised name RKO Radio Pictures. Selznick spent a mere fifteen months as RKO production chief, resigning over a dispute with new corporate president Merlin Aylesworth concerning creative control. One of his last acts at RKO was to approve a screen test for a thirty-three-year-old, balding Broadway song-and-dance man named Fred Astaire.

Selznick's tenure was masterful: In 1931, before he arrived, the studio had produced forty-two features for $16 million in total budgets. In 1932, under Selznick, forty-one features were made for $10.2 million, with clear improvement in quality and popularity. He backed several major successes, including A Bill of Divorcement (George Cukor, 1932), Katharine Hepburn's debut, and the monumental monster adventure King Kong (Merian C. Cooper, Ernest B. Schoedsack, 1933).

Still, the shaky finances and excesses that marked the company's pre-Selznick days had not left RKO in shape to withstand the Depression. The studio sank into receivership in early 1933, from which it did not emerge until 1940. Cooper took over as production head after Selznick's departure and oversaw two hits starring Hepburn: Morning Glory (Lowell Sherman, 1933), for which she won her first Oscar, and Little Women (George Cukor, 1933), one of the studio’s biggest box-office successes of the decade.

Ginger Rogers had already made several minor films for RKO when Cooper signed her to a seven-year contract and cast her in the big-budget musical Flying Down to Rio (Thornton Freeland, 1933). Rogers was paired with Astaire, making his film debut. Billed fourth and fifth respectively, the picture turned them into stars. Hermes Pan, assistant to the film's dance director, would become one of Hollywood's leading choreographers through his subsequent work with Astaire.

Along with Columbia Pictures, RKO became one of the primary homes of the screwball comedy. William A. Seiter directed the studio's first significant contribution to the genre, The Richest Girl in the World (1934). The drama Of Human Bondage (John Cromwell, 1934), was Bette Davis's first great success. George Stevens's Alice Adams (1935) and John Ford's The Informer (1935) were each nominated for the 1935 Best Picture Oscar—the Best Director statuette won by Ford was the only one ever given for an RKO production. The Informer's star, Victor McLaglen, also took home an Academy Award; he would appear in a dozen films for the studio over a span of two decades.

Fred Astaire. French postcard by Editions et Publications Cinematographiques, no. 89.

Bette Davis. Belgian collectors card by Chocolaterie Clovis, Pepinster. Collection: Amit Benyovits.

Victor McLaglen. French postcard by Ed. Chantal, Paris, no. 602. Photo: RKO.

Cary Grant. British postcard in the Picturegoer Series, London, no. W 609. Photo: R.K.O. Radio.

Douglas Fairbanks Jr. German postcard by Netter's Star Verlag, Berlin. Photo: RKO Radio Film. Publicity still for Gunga Din (George Stevens, 1939).

The brief but notable tenure of production chief Pandro S. Berman

Lacking the financial resources of industry leaders MGM, Paramount, and Fox, RKO turned out many pictures during the era that made up for it with high style in an Art Deco mode, exemplified by such Astaire–Rogers musicals as The Gay Divorcee (Mark Sandrich, 1934), their first pairing as leads, and Top Hat (Mark Sandrich, 1935). One of the figures most responsible for that style was another Selznick recruit: Van Nest Polglase, chief of RKO's highly regarded design department for almost a decade.

In, 1935, RKO premiered the first feature film shot entirely in advanced three-strip Technicolor, Becky Sharp (Rouben Mamoulian, 1935). Though judged by critics a failure as drama, Becky Sharp was widely lauded for its visual brilliance and technical expertise. In 1935, Cary Grant joined the studio's roster. Grant was a trendsetter, one of the first leading men of the sound era to work extensively as a freelancer, under nonexclusive studio deals, while his star was still on the rise. Ann Sothern starred in seven RKO films between 1935 and 1937, paired five times with Gene Raymond.

Walt Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) was the highest grossing production in the period between The Birth of a Nation (David Wark Griffith, 1915) and Gone with the Wind (Victor Fleming, 1939). While the Disney association was beneficial, RKO's own product was widely seen as declining in quality. Then, Pandro S. Berman accepted the position of production chief on a noninterim basis. His brief tenure resulted in some of the most notable films in studio history, including the adventure film Gunga Din (George Stevens, 1939), with Cary Grant and Victor McLaglen; Love Affair (Leo McCarey, 1939), starring Irene Dunne and Charles Boyer; and The Hunchback of Notre Dame (William Dieterle, 1939). Charles Laughton, who played Quasimodo in the latter, returned periodically to the studio, headlining six more RKO features. For Maureen O'Hara, who made her American screen debut in the film, it was the first of ten pictures she would make for RKO through 1952.

After co-starring with Ginger Rogers for the eighth time in The Story of Vernon and Irene Castle (H.C. Potter, 1939), Fred Astaire departed the studio. The Wheeler and Woolsey comedy series ended in 1937 when Woolsey became ill and died the following year. B-Western star George O'Brien made eighteen RKO pictures, sixteen between 1938 and 1940. With The Saint in New York (Ben Holmes, 1938), RKO successfully launched a B-detective series featuring the character Simon Templar that would run through 1943. The studio soon had another new B-comedy star in Lupe Vélez: The Girl from Mexico (Leslie Goodwins, 1939) was followed by seven frantic instalments of the Mexican Spitfire series, all featuring Leon Errol, between 1940 and 1943.

Pandro S. Berman departed RKO in December 1939 after policy clashes with studio president George J. Schaefer. Schaefer was keen on signing up independent producers whose films RKO would distribute. In 1941, the studio landed one of the most prestigious independents in Hollywood, Samuel Goldwyn's productions. The first two Goldwyn pictures released by the studio were highly successful: The Little Foxes (William Wyler, 1941) starring Bette Davis, garnered four Oscar nominations, while Ball of Fire (Howard Hawks, 1941) brought Barbara Stanwyck a hit under the RKO banner.

David O. Selznick loaned out his leading contracted director for two RKO pictures in 1941: Alfred Hitchcock's comedy Mr. and Mrs. Smith (1941) with Carole Lombard, was a modest success and the thriller Suspicion (1941) with Joan Fontaine and Cary Grant, a more substantial one, with an Oscar-winning turn by Joan Fontaine.

That May, having granted twenty-five-year-old star and director Orson Welles virtually complete creative control over the film, RKO released Citizen Kane (1941). While it opened to strong reviews and would go on to be hailed as one of the greatest movies ever made, it lost money at the time and brought down the wrath of the Hearst newspaper chain on RKO. The next year saw the commercial failure of Welles's The Magnificent Ambersons (Orson Welles, 1942)and the expensive embarrassment of his aborted documentary It's All True. The three Welles productions combined to drain $2 million from the RKO coffers, major money for a corporation that had reported an overall deficit of $1 million in 1940 and a nominal profit of a bit more than $500,000 in 1941.

Many of RKO's other artistically ambitious pictures were also dying at the box office and it was losing its last exclusive deal with a major star as well. Ginger Rogers, after winning an Oscar in 1941 for her performance in the previous year's Kitty Foyle (Sam Wood, 1940), held out for a freelance contract like Grant's. Schaefer resigned and departed a weakened and troubled studio, but RKO was about to turn the corner. Propelled by the box-office boom of World War II and guided by new management, RKO would make a strong comeback over the next half-decade.

With Schaefer gone, Charles Koerner did the job and brought the studio much-needed stability until his death in February 1946. In June 1944, RKO created a television production subsidiary, RKO Television Corporation, to provide content for the new medium. RKO became the first major studio to produce for television with Talk Fast, Mister, a one-hour drama filmed at RKO-Pathé studios in New York and broadcast by the DuMont network's New York station, WABD, on 18 December 1944. Koerner sought to increase its output of handsomely budgeted, star-driven features. However, the studio's only remaining major stars were Cary Grant, whose services were shared with Columbia Pictures, and Maureen O'Hara, shared with Twentieth Century-Fox.

So RKO arranged with the other studios to loan out their biggest names or signed one of the growing number of freelance performers to short-term, ‘pay or play’ deals. John Wayne appeared in the comedy A Lady Takes a Chance (William A. Seiter, 1943) while on loan from Republic Pictures. He was soon working regularly with RKO, making nine more films for the studio. Gary Cooper appeared in RKO releases produced by Goldwyn and, later, the start-up International Pictures, and Claudette Colbert starred in a number of RKO co-productions.

Ingrid Bergman, on loan out from Selznick, starred opposite Bing Crosby in The Bells of St. Mary's (Leo McCarey,1945). The top box-office film of the year, it turned a $3.7 million profit for RKO, the most in the company's history. Bergman returned in the co-productions Notorious (Alfred Hitchcock, 1946) and Stromboli (Roberto Rossellini, 1950), and in the independently produced Joan of Arc (Victor Fleming, 1948).

RKO and Orson Welles had an arm's-length reunion via The Stranger (Orson Welles, 1946), an independent production he starred in as well as directed. In December 1946, the studio released Frank Capra's It's a Wonderful Life (1946). While it would ultimately be recognised as one of the greatest films of Hollywood's Golden Age, at the time it lost more than half a million dollars for RKO. John Ford's The Fugitive (1947) and Fort Apache (1948), which appeared right before studio ownership changed hands again, were followed by She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949) and Wagon Master (1950); all four were co-productions between RKO and Argosy, the company run by Ford and RKO alumnus Merian C. Cooper.

Of the directors under long-term contract to RKO in the 1940s, the best known was Edward Dmytryk, who first came to notice with the remarkably profitable Hitler's Children (1943). Shot on a $205,000 budget, placing it in the bottom quartile of Big Five studio productions, it was one of the ten biggest Hollywood hits of the year. Another low-cost war-themed film directed by Dmytryk, Behind the Rising Sun (1943), released a few months later, was similarly profitable.

Much more than the other Big Five studios, RKO relied on B pictures to fill up its schedule. RKO had a history of making better profits with its run-of-the-mill and low-cost product than with its A movies. The studio's low-budget films offered training opportunities for new directors, as well, among them Mark Robson, Robert Wise, and Anthony Mann.

Robson and Wise received their first directing assignments with producer Val Lewton, whose specialised B-horror unit also included the more experienced director Jacques Tourneur. The Lewton unit's moody, atmospheric work — represented by films such as Cat People (Jacques Tourneur, 1942) with Simone Simon, I Walked with a Zombie (Jacques Tourneur, 1943), and The Body Snatcher (Robert Wise, 1945) — is now highly regarded. Johnny Weissmuller starred in six Tarzan pictures for RKO between 1943 and 1948 before being replaced by Lex Barker.

Film noir, to which lower budgets lent themselves, became something of a house style at the studio, indeed, the RKO B-Film Noir Stranger on the Third Floor (Boris Ingster, 1940) with Peter Lorre, is widely seen as initiating Noir's classic period. The studio's 1940s list of contract players was filled with Noir regulars: Robert Mitchum (who graduated to major star status) and Robert Ryan each made no fewer than ten film noirs for RKO. Gloria Grahame, Jane Greer, and Lawrence Tierney were also notable studio players in the field. Freelancer George Raft starred in two Noir hits: Johnny Angel (Edwin L. Marin, 1945) and Nocturne (1946). Tourneur, Mitchum, and Greer joined to make the A-budgeted Out of the Past (Edwin L. Marin, 1947), now considered one of the greatest of all Film Noirs. Nicholas Ray began his directing career with the Noir They Live by Night (1948), the first of a number of well-received films he made for RKO.

Charles Boyer and Irene Dunne. British postcard in the Film Partners Series, London, no. P 268. Photo: R.K.O. Radio. Publicity photo for Love Affair (1939, Leo McCarey).

Maureen O'Hara. Dutch postcard by J.S.A. Photo: M.P.E.

Orson Welles. French postcard by Editions du Globe, no. 143. Photo: Sam Lévin.

Claudette Colbert. Dutch postcard by S. & v. H., A. Photo: M.P.E.A.

Cary Grant and Ingrid Bergman. German collectors card. Photo: RKO Radio Film. Publicity still for Notorious (Alfred Hitchcock, 1946).

The capricious and fatal management style of Howard Hughes

RKO, and Hollywood as a whole, had its most profitable year ever in 1946. A Goldwyn production released by RKO, The Best Years of Our Lives (William Wyler, 1946), was the most successful Hollywood film of the decade. But the legal status of the industry's reigning business model was increasingly being called into doubt: the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Bigelow v. RKO that the company was liable for damages under antitrust statutes for having denied an independent movie house access to first run films—a common practice among all of the Big Five.

After Koerner's death, producer and Oscar-winning screenwriter Dore Schary took over his role. RKO appeared in good shape to build on its recent successes, but the year brought a number of unpleasant harbingers for all of Hollywood. The post-war attendance boom peaked sooner than expected and television emerged as a competitor for audience interest. Across the board, profits fell — a 27 percent drop for the Hollywood studios from 1946 to 1947.

The phenomenon that would become known as McCarthyism was building strength, and in October, the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) began hearings into Communism in the motion picture industry. Two of RKO's top talents, director Edward Dmytryk and producer Adrian Scott, refused to cooperate. As a consequence, they were fired by RKO per the terms of the Waldorf Statement, the major studios' pledge to "eliminate any subversives". Scott, Dmytryk, and eight others who also defied HUAC — dubbed the Hollywood Ten — were blacklisted across the industry. Ironically, the studio's major success of the year was Crossfire (Edward Dmytryk, 1947), a Scott–Dmytryk film.

For her performance in The Farmer's Daughter (H.C. Potter, 1947), a coproduction with Selznick's Vanguard Films, Loretta Young won the Best Actress Oscar the following March. It would turn out to be the last major Academy Award for an RKO picture. In May 1948, eccentric aviation tycoon and occasional movie producer Howard Hughes gained control of the company. During Hughes's tenure, RKO suffered its worst years since the early 1930s, as his capricious management style took a heavy toll. Production chief Schary quit almost immediately due to his new boss's interference and within weeks of taking over, Hughes had dismissed three-fourths of the work force. Production was virtually shut down for six months as the conservative Hughes shelved or cancelled several of the ‘message pictures’ that Schary had backed.

Once shooting picked up again, Hughes quickly became notorious for meddling in minute production matters, particularly the presentation of actresses he favoured. The production-distribution end of the RKO business, now deep in the red, would never make a profit again. Offscreen, Robert Mitchum's arrest and conviction for marijuana possession — he would serve two months in jail — was widely assumed to mean career death for RKO's most promising young star, but Hughes surprised the industry by announcing that his contract was not endangered.

Of much broader significance, Hughes decided to get the jump on his Big Five competitors by being the first to settle the federal government's antitrust suit against the major studios, which had won a crucial Supreme Court ruling in United States v. Paramount Pictures, Inc. Under the consent decree he signed, Hughes agreed to dissolve the old parent company, Radio-Keith-Orpheum Corp., and split RKO's production-distribution business and its exhibition chain into two entirely separate corporations — RKO Pictures Corp. and RKO Theatres Corp. — with the obligation to promptly sell off one or the other. While Hughes delayed the divorcement procedure until December 1950 and didn't actually sell his stock in the theatre company for another three years, his decision to acquiesce was one of the crucial steps in the collapse of classical Hollywood's studio system.

While Hughes's time at RKO was marked by dwindling production and a slew of expensive flops, the studio continued to turn out some well-received films under production chiefs Sid Rogell and Sam Bischoff, though both became fed up with Hughes's meddling and quit after less than two years. There were B Noirs such as The Window (Ted Tetzlaff, 1949), which turned into a hit, and The Set-Up (Robert Wise, 1949), starring Robert Ryan, which won the Critic's Prize at the Cannes Film Festival. The Thing from Another World (Christian Nyby, Howard Hawks, 1951), a science-fiction drama coproduced with Howard Hawks's Winchester Pictures, is a classic of the genre.

In 1952, RKO put out two films directed by Fritz Lang, Rancho Notorious and Clash by Night. The company also began a close working relationship with Ida Lupino. She starred in two suspense films with Robert Ryan — Nicholas Ray's On Dangerous Ground (1952) and Beware, My Lovely (Harry Horner, 1952), a coproduction between RKO and Ida Lupino's company, The Filmakers. Lupino was Hollywood's only female director during the period; of the five pictures The Filmakers made with RKO, Lupino directed three, including her now celebrated The Hitch-Hiker (Ida Lupino, 1953).

Exposing many filmgoers to Asian cinema for the first time, RKO distributed Akira Kurosawa's epochal Rashomon (1950) in the United States. The only smash hits released by RKO in the 1950s came out during this period, but neither was an in-house production: Goldwyn's Hans Christian Andersen (Charles Vidor, 1952) with Danny Kaye, was followed by Walt Disney's Peter Pan (Clyde Geronimi a.o., 1953). Convinced that the studio was sinking, Walt Disney ended his arrangement with RKO and set up his own distribution firm, Buena Vista Pictures. Howard Hughes had to leave and the new owners of RKO became General Tire.

By 1956, RKO's classic films were playing widely on television, allowing many to see such masterpieces as Citizen Kane (Orson Welles, 1941) for the first time. The $15.2 million RKO made on the deal convinced the other major studios that their libraries held profit potential — a turning point in the way Hollywood did business with television. The new owners of RKO, General Tire, made an initial effort to revive the studio, hiring veteran producer William Dozier to head production. In the first half of 1956, the production facilities were as busy as they had been in a half-decade. RKO Teleradio Pictures released Fritz Lang's final two American films, While the City Sleeps (1956) and Beyond a Reasonable Doubt (1956), but years of mismanagement had driven away many directors, producers, and stars.

The studio was also saddled with the last of the inflated B-movies such as Pearl of the South Pacific (Allan Dwan, 1955) and The Conqueror (Dick Powell, 1956) that enchanted Hughes. The latter, starring John Wayne, was the biggest hit produced at the studio during the decade, but its $4.5 million in North American rentals did not come close to covering its $6 million cost. After a year and a half without a notable success, General Tire shut down production at RKO for good at the end of January 1957. The Hollywood facilities were sold later that year for $6.15 million to Desilu Productions, owned by Desi Arnaz and Lucille Ball.

After numerous corporate reorganisations, the firm continued under the name RKO General, Inc., owning and operating radio and television stations, theatres, and related enterprises. Most of the films released by RKO Pictures between 1929 and 1957 have an opening ident displaying the studio's famous trademark, the spinning globe and radio tower, nicknamed the 'Transmitter'. It was inspired by a two-hundred-foot tower built in Colorado for a giant electrical amplifier, or Tesla coil, created by inventor Nikola Tesla. The studio's closing ident, a triangle enclosing a thunderbolt, was also a well-known trademark.

Finally, we cite Wikipedia in turn citing scholar Richard B. Jewell: "The supreme irony of RKO's existence is that the studio earned a position of lasting importance in cinema history largely because of its extraordinarily unstable history. Since it was the weakling of Hollywood's 'majors,' RKO welcomed a diverse group of individualistic creators and provided them...with an extraordinary degree of freedom to express their artistic idiosyncrasies.... [I]t never became predictable and it never became a factory.”

Robert Mitchum. British postcard in the Picturegoer Series, London, no. W 758. Photo: R.K.O. Radio.

Lex Barker. German postcard by Rüdel-Verlag, Hamburg-Bergedorf, no. 449. Photo: Alex Kahle / RKO Radio Film. Publicity still for Tarzan's Magic Fountain (Lee Sholem, 1949).

Gloria Grahame. German postcard by Kunst und Bild, Berlin, no. A 791. Photo: RKO. Publicity still for Sudden Fear (David Miller, 1952).

Tab Hunter. British postcard in the Picturegoer series, London, no. D 126. Photo: R.K.O. Radio.

Guy Madison. British postcard in the Picturegoer Series, London, no. W 815. Photo: R.K.O. Radio.

Sources: Encyclopaedia Britannica, Film Reference, Wikipedia and IMDb.

No comments:

Post a Comment