Swedish postcard by Axel Eliassons Konstförlag, Stockholm, no. 299. Photo: Skandia Film, Stockholm. Jenny Hasselqvist and Gösta Ekman in Vem dömer/Love's Crucible (Victor Sjöström, 1922).

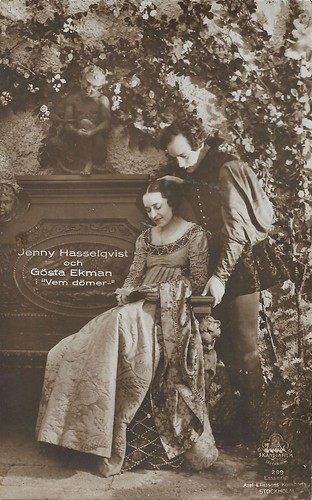

Swedish postcard by Axel Eliassons Konstförlag, Stockholm, no. 300. Photo: Skandia Film, Stockholm. Jenny Hasselqvist and Gösta Ekman in Vem dömer/Love's Crucible (Victor Sjöström, 1922).

Swedish postcard by Axel Eliassons Konstförlag, Stockholm, no. 301. Photo: Skandia Film, Stockholm. Jenny Hasselqvist and Ivan Hedqvist in Vem dömer/Love's Crucible (Victor Sjöström, 1922).

A film of extraordinary visual beauty

Vem dömer/Love's Crucible (1922) was Victor Sjöström’s follow up to Körkarlen/The Phantom Carriage (Victor Sjöström, 1921). The lavish production premiered on New Year’s Day in 1922 accompanied by the Red Kvarn Orchestra and a publicity campaign including an illustrated book of Hjalmar Bergman’s story. Paul Joyce at his blog Ithankyou: "Sjöström co-wrote the screenplay and whilst this tale of illicit period romance may appear atypical it has much in common with its predecessor and the director’s earlier work."

The story of Vem dömer/Love's Crucible (1922) takes place in the Catholic south and is shot largely on (vast) studio sets, so it lacks the location shooting and Nordic settings of Sjöström’s more famous works. However, a connection to how nature takes an active part and interferes with the plot of several more famous 'Golden Age' films can be found in how the use of fire – one of the classical elements of nature – is essential to the film’s conclusion. Just as characters in Terje Vigen/A Man There Was (Victor Sjöström, 1917) and Berg-Ejvind och hans hustru/The Outlaw and His Wife (Victor Sjöström, 1918) must endure extremes in order to survive, so must Jenny Hasselqvist’s Ursula overcome not just a physical test but also a moral one: she has to judge herself.

Contemporary reviewers criticised Vem dömer/Love's Crucible for being "artificial" and "lacking in soul", and these complaints were repeated by some later historians of the Swedish silent cinema. The film’s critical and commercial failure was readily linked to its supposed lack of specifically Swedish authenticity and heart, the Italianate, distinctly Catholic milieu obscuring the many continuities with earlier successes. While the weeping crucifixes and Christ-visions of this film are just as much realisations of the characters’ legend-filled world-view as the peasant paradise of Ingmarssönerna/The Sons of Ingmar (Victor Sjöström, 1919) and the death-cart of Körkarlen/The Phantom Carriage (Victor Sjöström, 1921), they may have sparked the uneasy suspicion in some critics that they were meant to preach rather than portray a superstitious religiosity.

In 1969, a duplicate negative of Vem dömer/Love's Crucible was made by the Svenska Filminstitutet from a nitrate positive source. A viewing print was struck from this negative the same year. In 2017, this print was presented at the Pordenone Silent Film Festival, Le Giornate del Cinema Muto. The musical accompaniment in the Verdi Theatre in Pordenone was by Neil Brand and Frank Bockius. Valerio Greco made a series of photos of the event.

In the festival catalog, Magnus Rosborn and Casper Tybjerg wrote: "A film of extraordinary visual beauty, Love’s Crucible has never held the canonical status of Sjöström’s better-known films, despite being known as a film that brought his directorial skills to Hollywood’s attention, leading to his American career two years later, and also despite the similar way it presents an unsparing, psychologically profound examination of marital hatred, guilt, and atonement wrapped inside an atmosphere of legend, old tales, and supernatural visitation. (...)

The evident artistry of the film – every shot is exactingly composed – goes against the myth of Sjöström as an instinctive artist, a rough-hewn naïf similar to the good-hearted peasants he sometimes played on screen. With its sumptuous renaissance setting, its vast sets, and its exquisitely crafted visuals, realized through the efforts of master cinematographer Julius Jaenzon, Love’s Crucible is a self-consciously masterful display of cinematic art and technique."

Swedish postcard by Axel Eliassons Konstförlag, Stockholm, no. 303. Photo: Skandia Film, Stockholm. Jenny Hasselqvist and Ivan Hedqvist in Vem dömer/Love's Crucible (Victor Sjöström, 1922).

Swedish postcard by Axel Eliassons Konstförlag, Stockholm, no. 304. Photo: Skandia Film, Stockholm. Jenny Hasselqvist and Gösta Ekman in Vem dömer/Love's Crucible (Victor Sjöström, 1922).

Swedish postcard by Axel Eliassons Konstförlag, Stockholm, no. 305. Photo: Skandia Film, Stockholm. Jenny Hasselqvist, Ivan Hedqvist, Tore Svennberg and Gösta Ekman in Vem dömer/Love's Crucible (Victor Sjöström, 1922). Nils Asther had a small part in this film. On this postcard, he is the man just left of Hasselquist.

Sources: Magnus Rosborn and Casper Tybjerg (Le Giornate del Cinema Muto); Paul Joyce (ithankyouarthur), IMDb, and Wikipedia (Italian).

No comments:

Post a Comment