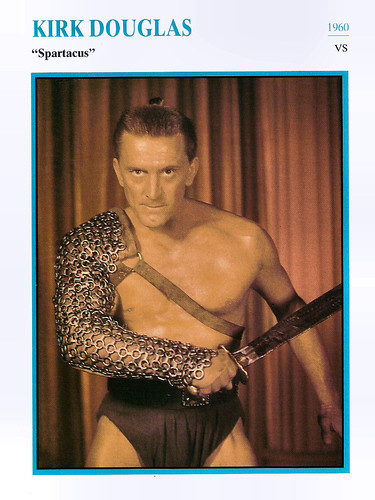

Spanish postcard by Archivo Bermejo, no. 7143. Photo: Universal International, 1960. Kirk Douglas in Spartacus (Stanley Kubrick, 1960).

Yugoslavian postcard by Z.K., no. 1399. Tony Curtis in Spartacus (Stanley Kubrick, 1960).

Spanish postcard by Archivo Bermejo, no. 7206. Photo: Universal International. John Gavin as Julius Caesar in Spartacus (Stanley Kubrick, 1960).

British postcard in the Cinema series. French affiche for Spartacus (Stanley Kubrick, 1960).

A very rebellious slave

Spartacus (Stanley Kubrick, 1960) is based on a novel by Howard Fast about the historical slave leader Spartacus. The story is situated in 73 B.C. The Roman Republic has slid into corruption, its menial work done by slaves. The hero is a Thracian slave working in a salt mine in Libya. Spartacus (Kirk Douglas) is known as a very rebellious person and after defending an older slave one day, he is sentenced to death by starvation.

Before that happens, however, Spartacus is spotted by Roman businessman Lentulus Batiatus (Peter Ustinov) who buys him with the plan to train him as a gladiator. Amid the abuse at the gladiatorial school, Spartacus forms a quiet relationship with Varinia (Jean Simmons), a serving woman whom he refuses to rape when she is sent to 'entertain' him in his cell. One day, the school is visited by wealthy Roman senator Marcus Licinius Crassus (Laurence Olivier), who aims to become the dictator of Rome. Crassus eventually buys Varinia, and for the amusement of his companions arranges for Spartacus and others to fight to the death. When Spartacus is disarmed, his opponent, an Ethiopian named Draba (Woody Strode), spares his life in a burst of defiance. Draba attacks the Roman audience, only to be speared in the back by a guard and killed by Crassus.

When Crassus then also takes Varinia as his slave, Spartacus has had enough. He calls on all the gladiators to revolt. Batiatus flees while the gladiators overwhelm their guards and escape into the countryside. Spartacus is elected chief of the fugitives and decides to lead them out of Italy and back to their homes. He starts training an army of slaves and gladiators, which soon grows to 70,000 men. The uprising soon spreads across the Italian Peninsula involving thousands of slaves. The slaves' plan is to acquire sufficient funds to buy ships from Silesian pirates who could then transport them to other lands from Brandisium in the south.

Spartacus is successful as his army wins one victory after another. He also finds Varinia again. The Roman Senate deployed all means to stop Spartacus' army. Every attempt fails and several Senate members retreat in shame over these defeats. The Roman Senate becomes increasingly alarmed as Spartacus defeats every army sent against him. Crassus' opponent the Roman Senator Gracchus (Charles Laughton) knows that his rival will try to use the crisis as a justification for seizing control of the Roman army. To try to prevent this, Gracchus channels as much military power as possible into the hands of his own protégé, the young senator Julius Caesar (John Gavin). Although Caesar lacks Crassus' contempt for the lower classes of Rome, he mistakes the man's rigid outlook for a patrician. Thus, when Gracchus reveals that he has bribed the Silesians to get Spartacus out of Italy and rid Rome of the slave army, Caesar regards such tactics as beneath him and goes over to Crassus.

Crassus uses a bribe of his own to make the pirates abandon Spartacus and has the Roman army secretly force the rebels away from the coastline towards Rome. Amid panic that Spartacus means to sack the city, the Senate gives Crassus absolute power. Now surrounded by Roman legions, Spartacus persuades his men to die fighting. Just by rebelling and proving themselves human, he says that they have struck a blow against slavery. In the ensuing battle, most of the slave army is massacred. The Romans try to locate the rebel leader for special punishment by offering a pardon (and return to enslavement) if the men identify Spartacus. Every surviving man responds by shouting "I'm Spartacus!". Crassus has them all sentenced to death by crucifixion along the Via Appia, where the revolt began.

French postcard in the Entr'acte series by Éditions Asphodèle. Mâcon, no. 001/27. Photo: Tony Curtis and Kirk Douglas at the set of Spartacus (Stanley Kubrick, 1960). Caption: Tony Curtis and Kirk Douglas discuss a film shot.

West German postcard by Ufa/Film-Foto, Berlin-Tempelhof, no. FK 4978. Photo: Universal International Films. Jean Simmons in Spartacus (Stanley Kubrick, 1960).

Romanian collectors card. Photo: Kirk Douglas and Peter Ustinov in Spartacus (Stanley Kubrick, 1960).

Spanish postcard by Archivo Bermejo, no. 7210. Photo: Universal International. John Gavin as Julius Caesar in the Technirama film Spartacus (Stanley Kubrick, 1960).

French postcard in the Entr'acte series by Éditions Asphodèle, Mâcon, no. 004/8. Photo: Collection B. Courtel / D.R. Laurence Olivier and Peter Ustinov on the set of Spartacus (Stanley Kubrick, 1960). Caption: Contrast of eras between the clothing of Laurence Olivier and that of the director and actor Peter Ustinov.

Clashes on the set

Kirk Douglas was the star of Spartacus (196O) and he was also the co-producer of the film through his company, Bryna Productions. Douglas had an unhappy time for most of the production. First, Douglas purchased the rights to Howard Fast's novel out of his own money. Universal agreed to finance the film after Douglas told them that he had secured Laurence Olivier, Charles Laughton and Peter Ustinov to appear in it. Author Howard Fast was originally hired to adapt his own novel as a screenplay, but he had difficulty working in the format. Douglas then insisted on hiring Dalton Trumbo to adapt the film against the wishes of the other producers. Trumbo had been blacklisted as one of the Hollywood 10, and intended to use the pseudonym 'Sam Jackson'. Trumbo had been jailed for contempt of Congress in 1950, after which he had survived by writing screenplays under assumed names. After the first week of shooting, Douglas had a major falling out with the original director, Anthony Mann. Mann was fired and according to Peter Ustinov, the salt mines sequence in the final film was the only footage shot by Mann. Douglas asked thirty-year-old Stanley Kubrick, with whom he had collaborated well three years previously on Paths of Glory (Stanley Kubrick, 1957), to direct. However, he had an equally difficult time working with Kubrick. Because he was only brought in at the last minute, Kubrick felt he had too little input in the final result and later disowned the film.

There were more clashes during production. Kubrick immediately fired Sabine Bethmann, who had only worked two days on the film. He and Douglas felt that she wasn't right for the role, so she was paid $3,000 to go home. Bethmann was replaced with Jean Simmons, who had been campaigning for the role. Saul Bass' main title sequence originally ran five minutes, but was cut to three and a half at Kubrick's insistence. Cinematographer Russell Metty walked off the set, complaining that Kubrick was not letting him do his job. Metty was used to directors allowing him to call his own shots with little oversight, while Kubrick was a professional photographer who had shot some of his previous films by himself. Subsequently, Kubrick did the majority of the cinematography work. Metty complained about this up until the release of the film and even, at one point, asked to have his name removed from the credits. However, because his name was in the credits when the film won the Academy Award for Best Cinematography, it was given to Metty, although he actually didn't shoot most of it. Kubrick spent $40,000 on the over-ten-acre gladiator camp set. On the side of the set that bordered the freeway, a 125-foot asbestos curtain was erected to film the burning of the camp, which was organised with collaboration from the Los Angeles Fire and Police Departments. Studio press materials state that 5,000 uniforms and seven tons of armour were borrowed from Italian museums and that every one of Hollywood's 187 stuntmen was trained in the gladiatorial rituals of combat to the death. The production used approximately 10,500 people. Eight thousand trained troops from the Spanish were used to double as the Roman infantry. Kubrick directed the armies from the top of specially constructed towers. In July 1959, Hollywood Reporter announced that the budget had "spiralled" from $5,000,000 to $9,000,000, and according to studio press materials, the final budget was $12,000,000.

The filming was also plagued by the conflicting visions of Kurbrick and screenwriter Dalton Trumbo. Kubrick complained that the character of Spartacus had no faults nor quirks, and was completely interchangeable with any other slave gladiator. As the blacklisted Trumbo wasn't allowed on the set, Kubrick could order re-writes without much opposition. The disagreements between Kubrick and Douglas got so bad that both men reportedly went into therapy together. After shooting, Kubrick was not allowed to be present during editing. This was the only occasion on which Kubrick did not exercise such control over one of his films. Dalton Trumbo still got his way. During the shooting, he was reportedly being smuggled into the studio several times under a blanket so that he could attend screenings of a rough cut of the film. This early version was deemed a disaster, and Trumbo made elaborate notes of what he perceived to be the problem with it. These notes were subsequently used to re-edit the film into its final form, which was well received. At first, the studio did not want to give the openly communist Trumbo screen credit for his screenplay. Douglas publicly announced that Trumbo was the screenwriter of Spartacus, and President John F. Kennedy crossed American Legion picket lines to view the film, helping to end blacklisting.

Universal Pictures' advertising campaign, which began in December 1959, declared that "1960 is the year of Spartacus." The world premiere was held on 22 September 1960, at the DeMille Theatre in New York City. The film parallels 1950s American history, specifically the House Committee on un-American Activities hearings and the civil rights movement. The hearings, where witnesses were ordered under penalty of imprisonment to 'name names' of supposed Communist sympathisers, closely resemble the climactic scene when the slaves, asked by Crassus to give up their leader by pointing him out from the multitude, each stand up to proclaim, "I am Spartacus". Author Howard Fast was jailed for his refusal to testify, and wrote the novel 'Spartacus' while in prison. The comment of how slavery was a central part of American history is pointed to in the beginning in the scenes featuring Draba and Spartacus. Draba, who denies the friendship of Spartacus claiming "gladiators can have no friends", sacrifices himself by attacking Crassus rather than killing Spartacus. This scene points to the fact that Americans are indebted to the suffering of black slaves, who played a major role in building the country - a fact then never mentioned in U.S. history books. The fight to end segregation and to promote the equality of African Americans is seen in the mixing of races within the gladiator school and in the army of Spartacus, where all fight for freedom.

Spartacus (1960) won four Academy Awards: Best Supporting Actor for Peter Ustinov, Best Cinematography, Best Art Direction and Best Costume Design. At the time of the film’s release, it was the biggest moneymaker in Universal Studios' history. Although the film was disowned by its director, Spartacus (1960) is now considered a classic. The original version included a scene where Marcus Licinius Crassus (Laurence Olivier) attempts to seduce the handsome slave Antoninus (Tony Curtis) in the bath. The Production Code Administration and the Legion of Decency both objected. At one point Geoffrey Shurlock, representing the censors, suggested it would help if the reference in the scene to a preference for oysters or snails was changed to truffles and artichokes. In the end, the scene was cut, but it was put back in for the 1991 restoration. However, the soundtrack had been lost in the meantime and the dialogue had to be dubbed. Tony Curtis was able to redo his lines, but Olivier had died. Joan Plowright, his widow, remembered that Anthony Hopkins had done a dead-on impression of Olivier and she mentioned this to the restoration team. They approached Hopkins and he agreed to voice Olivier's lines in that scene. Hopkins is thanked in the credits for the restored version. In 2017, Spartacus was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".

West German collector card by Ufa/Film-Foto, no. 26. Photo: Universal Film. Kirk Douglas in Spartacus (Stanley Kubrick, 1960).

West German collector card by Ufa/Film-Foto, no. 57. Photo: Universal Film. Laurence Olivier in Spartacus (Stanley Kubrick, 1960).

Dutch postcard, no. 860. Photo: Universal-Film. Jean Simmons in Spartacus (Stanley Kubrick, 1960). Collection: Geoffrey Donaldson Institute.

Spanish postcard by Archivo Bermejo, no. 7142. Photo: Universal International. John Gavin in Spartacus (Stanley Kubrick, 1960).

Dutch collectors card in the series 'Filmsterren: een Portret' by Edito Service, 1994. Photo: Collection Christophe L. Kirk Douglas in Spartacus (Stanley Kubrick, 1960).

Sources: Wikipedia (Dutch and English) and IMDb.

Truly one of the greatest films of all time.

ReplyDelete