French postcard by Editions Cinémagazine, no. 393. Photo: Ruth Harriet Louise / MGM. John Gilbert in The Big Parade (King Vidor, 1925).

Italian postcard by Casa Editrice Ballerini & Fratini, Firenze (B.F.F.), no. 199. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn, Roma (MGM). Lillian Gish in La Bohème (King Vidor, 1926).

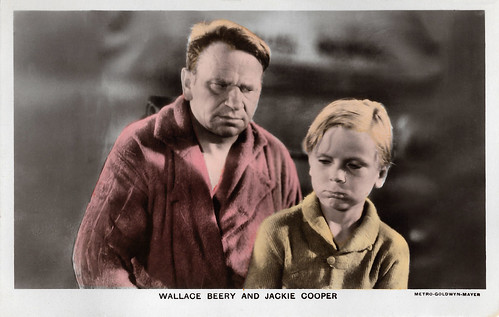

British postcard in the Film Partners Series, London, no. PC 71. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM). Wallace Beery and Jackie Cooper in The Champ (King Vidor, 1931).

Spanish postcard, 1953. Photo: Procines S.A. Gregory Peck and Jennifer Jones in Duel in the Sun (King Vidor, 1946).

One of the most commercially successful films of the entire silent film era

King Wallis Vidor was born in 1894 in Galveston, Texas. He was the son of Charles Shelton Vidor, a wealthy timber merchant and mill owner and Kate Lee Vidor (née Wallis). The 'King' in King Vidor is no sobriquet, but his given name in honor of his mother's favourite brother, King Wallis. As a child, he survived the great Galveston hurricane of 1900, which killed between 6,000 and 12,000 people. In 1980 Vidor recalled the horrors of the hurricane's effects: "All the wooden structures of the town were flattened ... [t]he streets were piled high with dead people, and I took the first tugboat out. On the boat I went up into the bow and saw that the bay was filled with dead bodies, horses, animals, people, everything."

Vidor attended grade school at the Peacock Military Academy, located in San Antonio, Texas. At the age of sixteen Vidor dropped out of a private high school in Maryland and returned to Galveston to work as a nickelodeon ticket taker. Fascinated by the new medium of cinema from an early age, he worked as a volunteer projectionist in his home town and made a few amateur films, including the short documentary Hurricane in Galveston (King Vidor, 1913). He sold footage from a Houston army parade to a newsreel outfit, The Grand Military Parade (King Vidor, 1913) and made his first fictional film concerning a local automobile race, In Tow (King Vidor, 1913).

King Vidor married the aspiring film actress Florence Arto in 1915. They went to Hollywood, where his young wife quickly became a star, known as Florence Vidor, in films by Frank Lloyd and Cecil B. DeMille. King worked in various positions before signing a contract with Universal as a director. David W. Griffith was his role model. His first full-length feature film was The Turn in the Road (King Vidor, 1919), for which he also wrote the screenplay. It was a film presentation of a Christian Science evangelical tract sponsored by a group of doctors and dentists affiliated as the independent Brentwood Film Corporation. Vidor would make three more films for the Brentwood Corporation, all of which featured as yet unknown comedienne Zasu Pitts, who the director had discovered on a Hollywood streetcar.

Shortly afterwards, he founded his own studio, Vidor Village, funded by First National. He made a series of inexpensive melodramas, often starring his wife. Vidor Village went bankrupt in 1922 and Vidor, now without a studio, offered his services to the top executives in the film industry. Louis B. Mayer engaged Vidor to direct Broadway actress Laurette Taylor in a film version of her famous juvenile role as Peg O'Connell in Peg o' My Heart. The success of Peg o' My Heart (King Vidor, 1922) landed him a contract with the old Metro Studios, which merged to form MGM in 1924. At MGM, he began a regular collaboration with star John Gilbert. Their first film together was His Hour (King Vidor, 1924), based on Elinor Glyn). In 1925, Vidor became one of Hollywood's most famous film directors with the war film The Big Parade (King Vidor, 1925), also starring John Gilbert. The film was not only a success with critics, but also one of the most commercially successful films of the entire silent film era. The Big Parade addressed the horrors of the First World War like no other film before it.

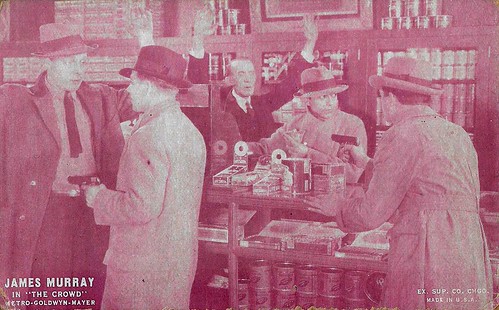

A year later, Vidor was chosen to direct Lillian Gish's debut at MGM, the opulent film version of La Bohème (King Vidor, 1926), in which John Gilbert again played the male lead. Both Gilbert and Vidor were in love with Gish at the time, but 'the Duse of the screen' did not follow up, as she recounted in her memoirs 'The Cinema, Mr. Griffith and Me'. Vidor established himself as one of the industry's innovative filmmakers with The Crowd (King Vidor, 1928), which was released in 1928 after a long filming period. The film tells the sad story of a married couple whose attempt to realise the American dream falls short of their expectations and threatens to fail.

Dutch postcard by M. Bonnist & Zonen, no. 115. Renée Adorée and John Gilbert in The Big Parade (King Vidor, 1925). Collection: Marlene Pilaete.

French postcard by Editions Cinémagazine, no. 192. Photo: R. Harriet Louise / Gaumont-Metro-Goldwyn. Karl (or Carl) Dane in the WWI drama The Big Parade (King Vidor, 1925).

Italian postcard by Fotocelere, no. 129. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM). Lillian Gish and John Gilbert in La Bohème (King Vidor, 1926).

French postcard, no. 510. Photo: Gaumont Metro Goldwyn. John Gilbert in Bardelys the Magnificent (King Vidor, 1926).

American Arcade card by Ex. Sup. Co. Chicago. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. James Murray in The Crowd (King Vidor, 1928).

A completely free hand in choosing his sound film debut

King Vidor made three comedies with 'the queen of the jet set', Marion Davies. Cosmopolitan Pictures, a subsidiary of MGM and controlled by influential newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst, insisted that Vidor direct Davies – Hearst's longtime mistress – in these Cosmopolitan-supervised films, to which Vidor acquiesced. Though not identified as a director of comedies, Vidor filmed three screwball-like comedies that revealed Davies's comedy talents. The Patsy (King Vidor, 1928) brought Marie Dressler and Dell Henderson, veterans of the Mack Sennett comedies, out of retirement to play Davies' farcical upper-class parents. Davies performs several amusing celebrity imitations of Lillian Gish, Pola Negri and Mae Murray.

The most enduring picture of the Vidor–Davies collaborations is Show People (King Vidor, 1928), one of Vidor's biggest commercial successes. The scenario was inspired by the glamorous Gloria Swanson, who began her film career in slapstick. Davis' character Peggy Pepper, a mere comic, is elevated to the high-style star Patricia Pepoire. Vidor also spoofs his own recently completed Bardelys the Magnificent (King Vidor, 1926), an over-the-top swashbuckling costume drama featuring romantic icon John Gilbert. Some of the best-known film stars of the silent era appeared in cameos, as well as Vidor himself.

Vidor's prestige was now so great that studio boss Louis B. Mayer gave him a completely free hand in choosing his sound film debut. With Hallelujah (King Vidor, 1929), Vidor chose a picture about rural black American life incorporating a musical soundtrack and explored numerous innovative possibilities that sound opened up in dramaturgy. Vidor's innovative integration of sound into the scenes, including jazz and gospel adds immensely to the cinematic effect. Hallelujah enjoyed an overwhelmingly positive response in the United States and internationally, praising Vidor's stature as a film artist and as a humane social commentator. Vidor was nominated for Best Director at the Academy Awards of 1929. Hallelujah is now regarded as the first film by a major Hollywood studio with an all-African-American cast, but at the time the film was a commercial flop.

Vidor's second sound film was his third and final film with Marion Davies, Not So Dumb (King Vidor, 1930), adapted from the 1921 Broadway comedy 'Dulcy' by George S. Kaufman. The limitations of early sound, despite recent innovations, interfered with the continuity of Davies' performance that had enlivened her earlier silent comedies with Vidor.

Vidor went on to make several less artistically ambitious but financially successful films. These included The Champ (King Vidor, 1931), about the friendship between an old alcoholic and washed-up boxer (Wallace Beery) who starts a comeback for the sake of a young boy (child star Jackie Cooper) and ends up dying in the ring. Wallace Beery earned an Oscar for Best Actor in a Leading Role for his role and it propelled him to top-rank among MGM stars. The film was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Picture and Vidor for Best Director.

Promotion card for Il Cinema Ritrovato, Bologna, 2017. Photo: Marion Davies (middle), Jane Winton, Orville Caldwell, Marie Dressler and Dell Henderson in The Patsy (King Vidor, 1928).

Italian postcard by Fotocelere no. 12. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Jackie Cooper in The Champ (King Vidor, 1931). Collection: Marlene Pilaete.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 161/3. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Jackie Cooper and Irene Rich in The Champ (King Vidor, 1931).

Dutch postcard by M. Bonnist & Zonen, Amsterdam, no. B 206. Photo: Loet C. Barnstijn. Dolores Del Rio and Joel McCrea in Bird of Paradise (King Vidor, 1932).

British postcard in the Film Weekly series. Photo: United Artists. Ronald Colman and Kay Francis in Cynara (King Vidor, 1932), a romantic drama film about a British lawyer (Colman) who pays a heavy price for an affair. Francis plays his wife.

A south seas romance

King Vidor was loaned to Radio-Keith-Orpheum (RKO) to make a 'South Seas' romance for producer David Selznick filmed in the US territory of Hawaii. Starring Dolores del Río and Joel McCrea, the tropical location and mixed-race love theme in Bird of Paradise (King Vidor, 1932) included nudity and sexual eroticism. During production Vidor began an affair with script assistant Elizabeth Hill that led to a series of highly productive screenplay collaborations and their marriage in 1937. Vidor divorced his second wife, actress Eleanor Boardman shortly after Bird of Paradise was completed.

The Stranger's Return (King Vidor, 1933) and Our Daily Bread (King Vidor, 1934) are Depression era films that present protagonists who flee the social and economic perils of urban America, plagued by high unemployment and labour unrest to seek a lost rural identity or make a new start in the agrarian countryside. Vidor's expressed enthusiasm for the New Deal and Franklin Delano Roosevelt's exhortation in his first inaugural in 1933 for a shift of labour from industry to agriculture. Our Daily Bread (King Vidor, 1934), a blazing appeal in favour of the New Deal with its depiction of an ideal community that renounces all approaches to capitalism in order to derive its values from communal property. The picture is the second film of a trilogy he referred to as 'War, Wheat and Steel'. His 1925 film The Big Parade was 'war' and his 1944 An American Romance was 'steel'.

During the 1930s Vidor, though under contract to MGM, made four films under loan-out to independent producer Samuel Goldwyn, formerly with the Goldwyn studios that had amalgamated with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer in 1924. Goldwyn's insistence on fidelity to the prestigious literary material he had purchased for screen adaptations imposed cinematic restraints on his film directors, including Vidor. Cynara (King Vidor, 1932), a romantic melodrama of a brief, yet tragic affair between a British barrister and a shopgirl, was Vidor's second sound collaboration with Goldwyn. Starring Ronald Colman and Kay Francis, the story by Francis Marion is a cautionary tale concerning upper- and lower-class sexual infidelities set in England.

In his third collaboration with Goldwyn, Vidor was tasked with salvaging the producer's huge investment in Soviet-trained Russian actress Anna Sten. Goldwyn's effort to elevate Sten to the stature of Dietrich or Garbo had thus far failed despite his relentless promotion when Vidor directed her in The Wedding Night (King Vidor, 1935). Despite good reviews the picture did not establish Sten as a star among film-goers and she remained 'Goldwyn's Folly'. The director was now mainly occupied with commercial material and his works from this period, such as his final and most profitable picture with Samuel Goldwyn, Stella Dallas (King Vidor, 1937) , were intelligently staged, perfectly choreographed films at a high level, which brought sophisticated material to the screen in a way that was also acceptable to broader social classes.

In 1939, Vidor would direct the final three weeks of primary filming for the classic film The Wizard of Oz (Victor Fleming, 1939). He directed the cyclone scene in Kansas. Although he was not credited in the credits and the scene was almost cut, he directed an unforgettable moment in the history of American cinema: the sequence in Kansas where Judy Garland sings the mythical song 'Over the Rainbow'.

British postcard by Film Weekly. Photo: MGM. Miriam Hopkins, Stuart Erwin, Franchot Tone and Lionel Barrymore in The Stranger's Return (King Vidor, 1933).

Dutch postcard by Loet C. Barnstijn. Photo: United Artists. Barbara Pepper, Tom Keene and Karen Morley in Our Daily Bread (King Vidor, 1934).

Latvian postcard. Anna Sten and Gary Cooper in The Wedding Night (King Vidor, 1935).

Belgian postcard by Kwatta, no. C. 99 (Serie C. 99-196). Photo: M.G.M. Hedy Lamarr in Comrade X (King Vidor, 1940).

Lust in the dust

In 1944, King Vidor was able to realise his pet project An American Romance (King Vidor, 1944), which describes the success story of an immigrant to the USA. The film had a record budget of three million dollars and lasted 140 minutes. MGM needed to increase the number of screenings and cut more than half an hour from the film on their own authority. The resulting film was a huge failure and marked the end of Vidor's collaboration with MGM. When he recalled this failure in his memoirs, Vidor seemed deeply affected by the experience.

In 1946, he directed the lavish and star-studded Western Duel in the Sun (King Vidor, 1946) for producer David O. Selznick. Filming dragged on for almost a year and was followed by endless arguments with the censor. The 'unbridled sexuality' portrayed by Vidor between Pearl (Jennifer Jones) and Lewt (Gregory Peck) created a furor that drew criticism from the US Congressmen and film censors, which led to the studio cutting several minutes before its final release. Selznick launched Duel in the Sun in hundreds of theaters, backed by a multiple-million dollar promotional campaign. Despite the film's poor critical reception (termed 'Lust in the Dust' by its detractors) the picture's box office returns rivaled the highest-grossing film of the year, The Best Years of Our Lives (William Wyler, 1946).

In the following years, Vidor made films for various studios, but his career increasingly sank into mediocrity. An exception is his best-known film from this period, The Fountainhead (King Vidor, 1949) with Gary Cooper and Patricia Neal, based on Ayn Rand's best-selling novel, a fictionalised version of the life of architect Frank Lloyd Wright. This lyrical and flamboyant film is one of the filmmaker's masterpieces and one of Gary Cooper's greatest performances.

He made more melodramas, such as the Film Noir Beyond the Forest (King Vidor, 1949) starring Bette Davis and Ruby Gentry (King Vidor, 1952) with Jennifer Jones. Then independent Italian producer Dino De Laurentiis offered him to create a screen adaption of Leo Tolstoy's vast historical romance of the late-Napoleonic era, 'War and Peace' (1869). His intelligent and epic War and Peace (King Vidor, 1956), starring Henry Fonda, Audrey Hepburn and Anita Ekberg, regained him the respect of critics.

War and Peace garnered Vidor further offers to film historical epics, but he chose the lavish biblical adaptation Solomon and Sheba (King Vidor, 1959), with Tyrone Power and Gina Lollobrigida tapped as the star-crossed monarchs. The shooting of the film was overshadowed by the sudden death of 45-year-old star Tyrone Power. Six weeks into production, Power suffered a heart attack during a climatic sword fight scene. He died within the hour. The entire film had to be re-shot, with the lead role of Solomon now recast with Yul Brynner. Solomon and Sheba was Vidor's last feature film.

Spanish postcard, no. 5292, 1953. Photo: Procines S.A.. Gregory Peck, Jennifer Jones, and Joseph Cotten in Duel in the Sun (King Vidor, 1946).

Italian postcard by Ballerini & Fratini, Firenze, no. 2248. Photo: United Artists. Jennifer Jones in Duel in the Sun (King Vidor, 1946). Collection: Marlene Pilaete.

Spanish postcard, no. 348. Photo: Warner Bros. Patricia Neal and Gary Cooper in The Fountainhead (King Vidor, 1949). Collection: Marlene Pilaete.

West German postcard by Kunst und Bild, Berlin, no. A 429. Photo: R.K.O. Ruth Roman in Lightning Strikes Twice (King Vidor, 1951).

Spanish postcard by Ed. Raker, Barcelona. Gina Lollobrigida in Solomon and Sheba (King Vidor, 1959).

The American director with the longest directing career

At the beginning of the 1960s, King Vidor largely retired from the screen and began teaching film theory at UCLA. He had already published his autobiography 'A Tree is a Tree' in 1953. In 1964, he won a special prize at the Edinburgh Film Festival. In 1979, he was finally awarded an honorary Oscar for his complete works, having been nominated five times for an Oscar himself. In the same year, he also released the documentary The Metaphor, which was his last directorial work.

In old age, he wrote the screenplay 'The Actor', inspired by the life of James Murray, the lead actor in The Crowd (King Vidor, 1928), whose alcoholism ruined his promising career and led to his early death. Robert De Niro and Ryan O'Neal were interested in the lead role, but Vidor was no longer able to realise the film. He last appeared in front of the camera for the comedy Love & Money (James Toback, 1981) and received much praise for his supporting role as the senile grandfather.

Vidor was married three times and worked together professionally with all three wives. He made numerous films with Florence Vidor during their marriage from 1915 to 1924. Their child Suzanne (1918-2003) was later adopted by Florence's new husband Jascha Heifetz. Vidor was married to actress Eleanor Boardman from 1926 to 1931; their daughters were Antonia (1927-2012) and Belinda (1930). Boardman played the female lead in The Crowd, among others. The later custody disputes over the two daughters were to accompany Vidor for a good two decades.

In 1932, he married Elizabeth Hill, who worked as a screenwriter on some of his films and with whom he remained together until her death in 1978. Vidor devoted the last 25 years of his life to painting. King Vidor died of heart disease at his ranch in Paso de Robles, California, in 1982 at the age of 88. After his death his ashes were scattered on the grounds of his ranch.

King Vidor's career as a director spanned a total of 67 years from 1913 to 1980, which even earned him an entry in the Guinness Book of Records as the American director with the longest directing career. Critics find it difficult to discern a clearly recognisable style in Vidor's work: He frequently oscillated between his own dream projects and routine productions for the major Hollywood studios. Like many Hollywood directors of his time, he directed films from almost all genres, but he was also an experimental director who sought a certain narrative style based on the subject matter and not the other way round.

Sources: Wikipedia (German, French and English), and IMDb.

No comments:

Post a Comment