American postcard by Kline Poster Co. Inc., Philadelphia. Photo: Fox. Theda Bara in Carmen (Raoul Walsh, 1915).

To introduce her to the public, two Fox publicity agents, John Goldfrap and Al Selig launched an astonishing advertising campaign, inventing a foreign background for their new star. They claimed that Theda was born in Egypt, in the shadow of the Sphinx, to an Italian artist and a French actress and that she had been a stage star in Paris before coming to the U.S.A. None of this was true. It’s commonly assumed that those rather far-fetched stories were not meant to be taken seriously but that they were created to offer entertaining and escapist reading to thrill-seeking audiences. Anyway, it should be noted that, as early as mid-1915, several newspapers had begun to reveal that Theda was, in fact, a Cincinnati-born girl. With her heavily kohl-rimmed eyes and her racy on-screen persona, she offered for sure a distinct contrast to child women such as Mary Pickford or healthy and spunky serial heroines such as Pearl White. The public was delighted to see an actress whose primary attraction was her sexuality.

Later, Fox's publicity department came up with other weird stories, declaring e.g. that the souls of Delilah, Lucrezia Borgia and the bloody countess Elizabeth Bathory were reincarnated in Theda’s mind, that a physician had discovered that the actress had the muscular system of a serpent or that her contract included several special clauses, such as forbidding her to marry or to appear in public without veils. Photos of an unveiled and smiling Theda selling Liberty Bonds in New York in the fall of 1917 seems to indicate that this bizarre contract either was not intended to be fulfilled or only existed in Goldfrap and Selig’s minds.

Theda Bara herself was quite ambivalent about this kind of publicity. On the one hand, she knew that such outlandish press coverage stereotyped her. On the other hand, she was well aware of the value of her transgressive and exotic image. So she played the game by mentioning for example an emerald ring which "had been given to her by a blind sheikh", by declaring that she was deeply attached to two statuettes of Egyptian God Amen Ra which "have been bought in a Paris shop when she was a child" or by pretending, at the time of Carmen, that she had lived in Spain in one previous life.

From 1915 to 1919, she starred in an amazing output of thirty-nine movies and her successes enabled William Fox to lay the groundwork for his empire. In private, Theda Bara was quite unlike her image. In her heyday at Fox, she lived quietly with her mother and her sister, her off-screen reputation unblemished by any scandal or misbehaviour. She only married once, to director Charles Brabin in 1921, and their happy union lasted until her death in 1955.

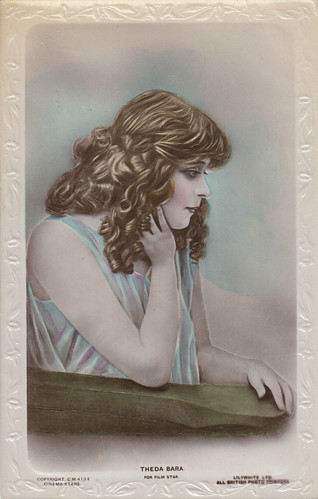

British postcard by Lilywhite in the Cinema Stars series, no. C.M. 94. Photo: William Fox. Theda Bara in Salome (J. Gordon Edwards, 1918).

British postcard by Lilywhite in the Cinema Stars series, no. C.M. 413D. Photo: William Fox. Theda Bara in Salome (J. Gordon Edwards, 1918).

Theda Bara before she became the queen of vamps

Theda Bara was born Theodosia Goodman on the 29th of June 1885 in Cincinnati, Ohio, U.S.A. Her father was a Jewish Polish-born tailor and her mother was born in Switzerland.

From an early age, she was fascinated by acting and, after having spent two years at Cincinnati University, she dropped out in 1905 to go on stage. The following years are not very well documented.

Confirmed appearances include a small role in Ferenc Molnar’s 'The Devil on Broadway' in 1908 and touring in a road company with the musical 'The Quaker Girl' in 1911.

Her stage career going nowhere, she decided to give movies a try. She made her film debut at Pathe with a bit role in Frank Powell’s The Stain (1914). He took interest in her as he liked the way she photographed and reacted to direction.

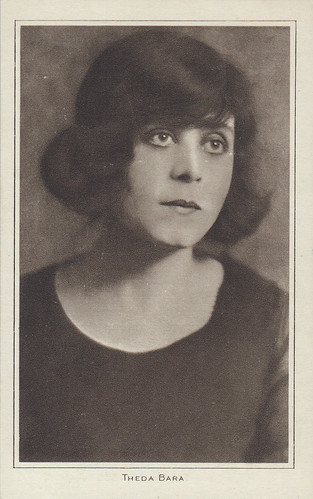

British postcard by Lilywhite Ltd, no. C.M. 29. Photo: William Fox.

British postcard by Lilywhite Ltd, no. C.M. 410 B. Photo: Sarony, New York / William Fox.

British postcard in the Famous Cinema Stars series by J. Beagles & Co. Ltd. London, no. 132. B.

A Fool There Was

'A Fool There Was' was a 1909 Broadway play, inspired by an 1897 Rudyard Kipling poem called 'The Vampire', itself inspired by a painting. The play, which was also adapted into a book, tells the story of a diplomat falling into the clutches of an evil seductress, who ruins his life. William Fox bought the rights and hired Frank Powell to direct the film version.

At his suggestion, Fox signed, in the fall of 1914, the unknown Theodosia to play the leading female role. She was quickly rebaptised Theda Bara, Theda being a diminutive of Theodosia and Bara coming for her maternal grandfather’s name, Baranger. A Fool There Was was released in January 1915. It was a huge hit and made Theda Bara a star overnight.

Of course, it was not the first time that a temptress had been depicted in an American movie but it was certainly the first time that it was done with such force and carnal power. The heroine has absolutely no redeeming features in her actions. In the course of the plot, we see for example that one of her former victims had become a skid-row bum.

"See what you have done to me, and still you prosper, you hellcat", he says to a haughty Theda, who quickly asks a policeman to move the poor chap away. When another of her discarded ex-boyfriends confronts her, armed with a gun, she just calmly answers him "Kiss me my Fool" and, still under her spell, he shoots himself. Furthermore, her unnamed character, simply called 'The Vampire' all through the film, is not even punished in the end. Indeed, a triumphant Theda is seen in the final reel scattering flower petals over her lover’s lifeless body and we are left to imagine her ready to move on to other prey.

We can easily imagine the shock it had been to audiences at that time to see such an evil, unrepentant and erotically charged character. The New York Dramatic Mirror wrote: "Miss Bara misses no chance for sensuous appeal in her portrayal of the Vampire. She is a horribly fascinating woman, vicious to the core, and cruel". And, for the New York Morning Telegraph, the Vampire was "quite the most revolting but fascinating character that has appeared upon the screen for some time".

British postcard by Lilywhite Ltd, no. C.M. 413 E. Photo: William Fox.

British postcard in the Famous Cinema Stars series by J. Beagles & Co. Ltd. London, no. 132a. Photo: William Fox.

Fox’s undisputed queen

After A Fool There Was, Theda Bara stole her sister’s husband in Kreutzer Sonata (1915), was an unfaithful and depraved wife in The Clemenceau Case (1915) and wrecked a sculptor’s marital bliss in The Devil’s Daughter (1915). By now, she had become firmly associated with vampire roles and the abbreviation 'vamp' soon became a household word. After the disappointing box-office receipts of Lady Audley’s Secret (1915) and The Two Orphans (1915), in which she played more restrained characters, Fox wisely put her back on the vamping track in films such as Sin (1915), Carmen (1915), Destruction (1915), The Serpent (1915) or Gold and the Woman (1916). Needless to say, some of her films met with censorship problems.

From time to time, usually at her demand, she was again given non-vamping parts such as in East Lynne (1916), Under Two Flags (1916), Romeo and Juliet (1916), Her Greatest Love (1917) or Heart and Soul (1917) but it seemed that her fans always preferred her as a femme fatale. They were thrilled to see her for example in The Vixen (1916), in which her character proclaims: "It’s true that I have no heart but then, I am more comfortable without one", and in The Tiger Woman (1917), which caused one reviewer to write: "The wholesome damage that strews her pathway would put a Kansas cyclone to shame".

Just after having played the famous French courtesan Marguerite Gautier in Camille (1917), she starred in the most prestigious film of her career, the lavish Cleopatra (1917). Never to be outdone, Fox advertising services reported the discovery, in a tomb of the ancient Egyptian city of Thebes, of an inscription found on an antique stone wall forecasting the coming of Theda Bara several centuries later. The fact that her pseudonym was an anagram of 'Arab Death' added extra spice to this odd story. Theda herself suggested that she was a reincarnation of the last queen of Egypt.

All this was good publicity playfulness and was great fun to read. The risqué costumes she wore (such as a snake bra and other revealing brassieres) didn’t go unnoticed and attracted much comment. She most probably had never displayed so much flesh before. Cleopatra was one of the most popular films of 1917 and cemented her position as Fox’s nr 1 moneymaker. She later appeared in two other special big-budgeted productions, Madame du Barry (1917) and Salome (1918). In August 1918, the actress came tenth in a popularity poll held by Motion Picture Magazine, above Charlie Chaplin, who ranked 17th.

As 1919 went by, the Theda Bara vogue was beginning to wane. When Men Desire (1919), The Siren’s Song (1919) and A Woman There Was (1919) didn’t do too well at the box office. Tired of vamp roles, she then elected to play a virginal Irish peasant in Kathleen Mavourneen (1919). Unfortunately, Irish societies strongly objected to the movie. Faced with threats and riots, several theatres quickly withdrew Kathleen Mavourneen and some even preferred not to show it. After this debacle, Theda’s high hopes to give a new impetus to her career were dashed and her Fox contract came to an end with two more films, La Belle Russe (1919) and The Lure of Ambition (1919).

Swedish postcard by Ljunggrens Konstförlag Stockholm, no. 293.

British postcard by Pictures Portrait Gallery, no. 4. Photo: Fox. Theda Bara in Romeo and Juliet (J. Gordon Edwards, 1916).

A former vamp’s new lease on life

As film offers didn’t pour in, she accepted to star in the play 'The Blue Flame'. She played it to very good business in several cities before it hit Broadway on the 15th of March 1920. The critics were merciless but newspapers noted that, nevertheless, it drew large crowds. Audiences were eager to see Theda in person. On top of her regular salary, Theda had shrewdly negotiated a fifty percent interest in the play, which brought her a hefty profit.

After 'The Blue Flame' closed on Broadway, she went on a successful tour with it. In 1921, she accepted a lucrative offer to appear in a vaudeville act and went on tour again all across the U.S.A. In 1922, it was announced that she had signed a one-film contract with Lewis Selznick but nothing ever came of it.

Theda came back on the screen in The Unchastened Woman (1925), produced by a small company called Chadwick Pictures, but it failed to generate much interest. She then signed with Hal Roach to appear in a series of comedy shorts. She only made one, Madame Mystery (1926), and soon asked to cancel her contract. It was her last movie.

Later, she made her final stage appearance in Los Angeles in 1934 with 'Bella Donna', in a five-night engagement, and she occasionally took part in radio shows. But, mostly, she simply chose to enjoy life. Free from want, she became a well-known social figure, often giving parties at her Beverly Hills house. She was reputed to be a witty, cultured and engaging hostess, noted for the delicious dishes she served to her guests.

A long way from her former portrayals of homewreckers and man-eaters, she formed a happy and long-lasting couple with her husband, Charles Brabin. In her final years, she settled into a calm and peaceful existence and she allegedly used to bake cookies for neighbourhood children, who probably had no idea that this kind old lady had once been the wickedest woman on the screen. Theda Bara died on the 7th of April 1955, from abdominal cancer.

British postcard by Pictures Portrait Gallery, no. 146.

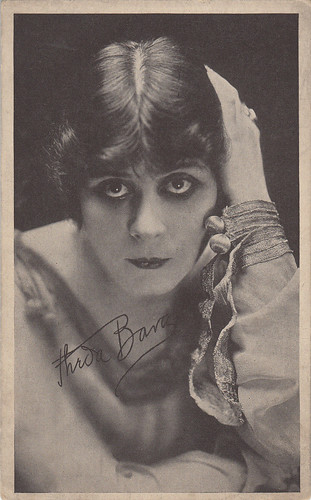

American postcard, no. 125, signed in 1919.

Theda’s legacy

In 1958, Life magazine invited Marilyn Monroe and photographer Richard Avedon to recreate images of five celebrated actresses of different eras. Theda was part of the selection, alongside Lillian Russell, Clara Bow, Marlene Dietrich and Jean Harlow. In the 1960s, a photo of Theda Bara in Salome adorned the cover of the British counterculture newspaper International Times.

Her eyes were also used for the logo of the Chicago film festival. Even in the French film Le distrait (1970), a Theda Bara poster can be seen on the wall of Pierre Richard’s office. In 1994, she was one of ten silent stars honoured with a U.S. postal stamp, in a caricature by Al Hirschfeld. Today, she is one of the very few stars from the silent era whose name still has a certain significance.

Only four of her starring movies are known to be extant. Unfortunately, they don’t permit us to really judge her as an actress. A Fool There Was (1915) has undoubtedly important historical value but can appear to some as rather crudely made. East Lynne (1916), in which she played an ill-fated divorcee, is not representative of her body of work at Fox. As for The Unchastened Woman (1925) and Madame Mystery (1926), they have been produced when she was not in her prime anymore.

Silent movie buffs still strongly hope that some other Theda Bara vehicles will be discovered one day. It’s not a coincidence that the American Film Institute has included Cleopatra on its 'Ten Most Wanted' list of lost films.

Nevertheless, we are lucky to have plenty of photos of Theda Bara. On several of them, she is seen in a sultry or exotic mood, lying over a skeleton, appearing in revealing outfits or posing with crystal balls or buddhas. But she also looks less flamboyant, even demure, in other shots. Her portraits seem to corroborate that, maybe, there was some truth in what Theda Bara said several times in interviews, namely that she was a more versatile actress than her vamp image would have let thought.

American postcard by Kraus Mfg. Co., New York.

British postcard by Hardie, Aberdeen. Photo: Fox. Theda Bara in The Rose of Blood (J. Gordon Edwards, 1917).

American postcard by White, 370 East 23D Street, Brooklyn, N.Y.

Text and postcards: Marlene Pilaete.

What fascinating images. Thank you

ReplyDelete