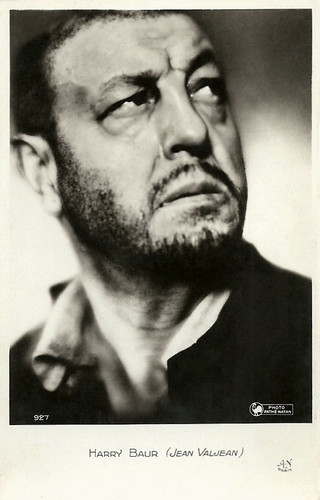

French postcard by A.N., Paris, no. 936. Photo: Pathé Natan. Harry Baur as Jean Valjean in Les Misérables (Raymond Bernard, 1934), based on the novel by Victor Hugo.

French postcard by A.N., Paris, no. 6684. Photo: Gaumont-Franco Film-Aubert (G.F.F.A). Harry Baur and Jackie Monnier in David Golder (Julien Duvivier, 1931).

French postcard in the series Nos artistes dans leur loge, no. 202. Photo: Comoedia.

French postcard by A.N., Paris. Photo: Pathé Natan. Publicity still for Les Misérables (Raymond Bernard, 1934).

French postcard by Edition Chantal, Paris. Photo: publicity still for Un Carnet de Bal/Dance Program (Julien Duvivier, 1937).

A man of substance

Henri-Marie Rodolphe Baur, better known as Harry Baur, was born in Paris in 1880. His parents were Catholics from the Alsace; his father came from Mulhouse, and his mother from Bitche en Moselle. They were ruined after theft and had to move to ever more modest dwellings. Baur’s father died when Harry was 10, so his mother and his sister Blanche raised him.

He first did college at Saint-Nazaire. To escape the religious education his family wanted him to take, he fled to Marseille and joined the rugby team of the XVth Olympic Games in Marseille. Here he started studies at the École d'Hydrographie and enrolled in various odd jobs such as peddler, carter, braider of funeral wreaths etc. Slowly he managed to start a career as a stage actor.

As he was refused at the Conservatoire in Paris, he took private lessons. He first enlisted at the Comédie Mondaine in 'Le Filleul du 31'. He then received his first awards for tragedy in 'Le Cid' and for comedy with 'L'Avare' at the Conservatoire in Marseille, while he did military service in Le Mans. He became the secretary of the famous actor-director Mounet-Sully. From 1904 on, he played in numerous Parisian theatres: Comédie Mondaine, Grand Guignolalais-Royal, and Mathurins. Later he also played with Gémier and Antoine.

Because of a beginning facial paralysis, he didn’t have to do service when war broke out in 1914, so he continued to play at the Gaîté-Lyrique, the Ambigu, the Porte Saint-Martin, the Gymnase, the Édouard VII, the Variétés, etc. Baur also collaborated as a film reviewer for 'Crapouillot', under the pseudonym of Orido de Fhair. By the early 1910s, Baur had become not only a man of substance in the diversity of his career, but also physically. Between 1909 and 1914, Harry Baur also performed in almost 30 silent films. He started at Eclair with Beethoven (Victorin Jasset, 1908) from 1909 on he worked at Pathé as well, a.o. in the Vidoq films (1909-1911), and the Film d’Art films such as L’Assommoir/Drink (Albert Capellani, 1909) after Émile Zola. At Eclair he worked a.o. with director Maurice Tourneur in Monsieur Lecoq/Mr. Lecoq (1914).

With Mistinguett, Baur played in Fleur de Paris/Flower of Paris (André Hugon, 1916) and Chignon d’or/The Gold Chignon (André Hugon, 1916), and with Albert Dieudonné in Sous la griffe/Under the label (Albert Dieudonné, 1921). In La voyante/The Clairvoyant (Leon Abrams, Louis Mercanton, 1923) he played opposite the legendary Sarah Bernhardt. Between 1924 and the arrival of French sound film Baur was away from the screen and focused on the stage. In 1910 he married actress Rose Cremer, known as Rose Grande, and they had three children. In 1931 Rose died during a trip to Algeria. Baur then married Rika Radifé, a stage actress as well, and of Turkish origin (her real name was Rebecca Behar).

French postcard by Editions et Publications cinématographigues (EPC), no. 81.

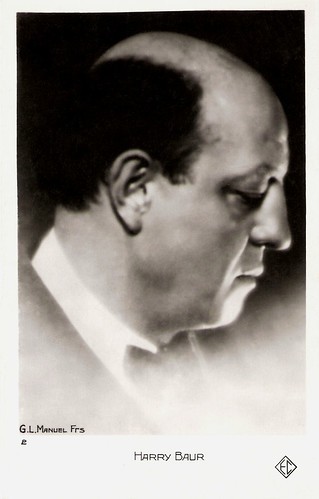

French postcard by Editions E.C., Paris, no. 2. Photo: G.L. Manuel Frères, Paris.

French postcard by EC, no. 2. Photo: Pathé-Natan.

Baur’s most important director during the 1930s

In 1931 Harry Baur had a triumph on stage with his interpretation of César in Marcel Pagnol’s play 'Fanny', the sequel to his 'Marius'. Baur had substituted the great Raimu in this role and would become a fierce competitor to the actor all through the 1930s, both on stage and on screen. Earlier in 1931, one of Baur’s first sound films had been released, the drama David Golder, directed by Julien Duvivier, who supposedly had brought Baur back to the screen. Duvivier would become Baur’s most important director during the 1930s. The timing of David Golder is not entirely clear, as in 1931 Baur also went to London to act in an early French talkie shot there at British International Pictures: the multilingual Le cap perdu (Ewald André Dupont, 1931). Le cap perdu/Cape Forlorn was quickly forgotten, but David Golder was a huge success in France at the time. The film about a betrayed Jewish banker was almost shot like a silent film at the Basque Coast. It was a clever streak of Duvivier to relaunch Harry Baur as a film actor with this topic. Baur had already been successful in a stage version at the Théâtre de la Porte Saint-Martin in Paris.

In March 1931, when David Golder was released in France, Baur started production for Le juif polonais/Polish Jew (Jean Kemm, 1931), about a man who is haunted by his murder. The film was especially created for Baur to excel but it wasn’t as lucrative as David Golder. After this followed Criminel/Criminal (Jack Forrester, 1932), an alternate language version of The Criminal Code (Howard Hawks, 1931). Baur played a prison warden, while Jean Servais made his film debut as an innocently condemned young man who is involved in a crime within the prison.

After this, Baur played in three films by Julien Duvivier. The first was Les cinq gentlemen maudits/Moon Over Morocco (1932) with René Lefèvre and Robert Le Vigan. Parallel Duvivier shot a German version with Adolf Wohlbruck, Camilla Horn and Jack Trevor. Exteriors were shot at Fez, Marrakech and Moulay-Idriss. The press praised Duvivier’s taste for atmosphere, picturesque and exoticism. Next was the adaptation of Jules Renard’s novel Poil de Carotte/The Red Head (Julien Duvivier, 1932), with Baur as the unforgettable Monsieur Lepic next to the young Robert Lynen (Both actors would share the same, tragic destiny, as Lynen was a member of the Resistance in the war, was imprisoned in 1943 and executed by the Germans in 1944). For his sound version of Poil de Carotte, Duvivier borrowed from other works of Renard as well, such as 'La Bigote' (The Bigote). In 1926 Duvivier had already made a silent version with André Heuzé as Poil de Carotte and Henry Krauss as M. Lepic. Baur had a very precise idea of how to play Lepic and was a perfectionist in his creation. Poil de Carotte had a prosperous release in Paris in 1932, with praise for Harry Baur.

Not wanting to let go of his star, Duvivier had him play commissaire Jules Maigret in La tête d’un homme/A Man's Neck (Julien Duvivier, 1932). While author Georges Simenon thought at the time that Baur was too old for the part and too tragic, the film is now considered one of the best adaptations of Simenon's novels. In 1932 Baur played Monsieur de Tréville, captain of the King’s guards in a very florishing sound version of Les trois mousquetaires/The Three Musketeers (1932). A decade earlier, director Henri Diamant-Berger had done a silent version, a serial in 12 episodes. Now it was a two-part sound version, entitled Les ferrets de la reine/The Queen's Studs and Milady.

Baur was coupled with Pierre Blanchar in Cette vieille canaille/The Old Devil (Anatole Litvak, 1933). While Baur did not convince as a clochard who is a distant relative of the Rothschild family in Rotchild (Marco de Gastyne, 1933), he came back full fling as Jean Valjean in Les Misérables (Raymond Bernard, 1933), an adaptation of Victor Hugo’s classic novel. Costars were Charles Vanel as Javert and Josseline Gael as Cosette. Because of its length, the film was released in two parts. It became Baur’s best film performance and some say the best film interpretation of Hugo’s famous character. Because of the European success, Baur received offers from Hollywood, but he didn’t want to leave Paris and declined.

Dutch postcard. Photo: Fim Film, Amsterdam. Harry Baur in Poil de carotte/The Red Head (Julien Duvivier, 1932).

br />

Dutch postcard. Photo: Filmex, Amsterdam. Madeleine Guitty and Harry Baur in Cette vieille canaille/The Old Devil (Anatole Litvak, 1933).

br />

Dutch postcard. Photo: Filmex, Amsterdam. Madeleine Guitty and Harry Baur in Cette vieille canaille/The Old Devil (Anatole Litvak, 1933).

French postcard by A.N. Paris, no. 941. Photo Pathé Natan. Harry Baur as Jean Valjean and Max Dearly as Gillenormand in Les Misérables (Raymond Bernard, 1934).

A remake of an expressionist classic

After two lesser films, Harry Baur was back with Les nuits moscovites/Moscow Nights (Alexis Granowski, 1934), also the debut of Neapolitan singer-actor Tino Rossi. Harry Baur played a course, rich Russian wheat trader, opposite Annabella and Pierre-Richard Wilm. The success of the film caused producers to offer Baur one ‘Russian’ film after another. At the time films shot by and featuring fled White Russians were popular in France. After that it is time to play Herod in Golgotha (Julien Duvivier, 1935), co-starring Jean Gabin as Pontius Pilate, Robert le Vigan as Jesus and Edwige Feuillère as Claudia Procula.

General Production offered Baur the part of Judge Porphyre in Crime et chatiment/Crime and Punishment (Pierre Chenal, 1935), based on Dostoievski’s novel. The confrontation between Baur and his costar Pierre Blanchar was the climax of this thriving film, which launched the career of Chenal in the 1930s. The sets of the film were highly stylized, inspired by German Expressionism. This might have inspired Duvivier to do a remake of the Expressionist classic Der Golem by Paul Wegener: Le Golem/The Golem (Julien Duvivier, 1935), with Baur playing Emperor Rudolph and with shooting at studios in Prague, where the story takes place. Baur then went to London for an English version of Nuits moscovites, Moscow Nights (Anthony Asquith, 1935) with a young Laurence Olivier.

Maurice Tourneur, with whom Baur had worked together in the 1910s, then shot Samson (1936), a modern drama based on a play by Henry Bernstein. It had already been adapted for the silent cinema and involved adultery and the power of money. Gaby Morlay and Baur were the central couple whose silences were as telling as their words. Then it was imperial Russia time again with Les yeux noirs/Black Eyes (Viktor Tourjansky, 1936) with Baur and Simone Simon, before moving over to the Hungarian steppes for Tarass Boulba/Taras Bulba (Alexis Granowsky, 1936), based on Gogol’s novel. It was both critically and commercially Baur’s biggest success since Les Misérables. The wild and intense Boulba matched Baur perfectly and his performance impressed audiences. For Les hommes nouveaux/The New Men (1936), director Marcel L’Herbier shot the first documentary part on the pacification of Morocco with actor Gabriel Signoret made up as marshal Lyautey, whom all thought had a striking resemblance. Baur had a supporting part as Maurice de Tolly, inspector general. While the film was a clear colonial product, L’Herbier’s most important drive was to ignite the fire of national patriotism in light of the growing German military force. A young Jean Marais had one of his first roles here.

Abel Gance gave Baur a great part in the title role of Un grand amour de Beethoven (1936), a character that Baur already had played in his first film. After a break in Italy, Duvivier asked Baur to play a man turned Dominican monk in his well-known bitter film Un carnet de bal/Dance Program (Julien Duvivier, 1937). In the film, a young widow (Marie Bell) revisits the dancers from her old booklet, but they are all disappointments. The film was a worldwide success and was awarded the Coppa Mussolini for best foreign film in Venice. Next Baur took the boat to Algeria for the shooting of Sarati le Terrible/Sarati the Terrible (André Hugon, 1937) in which Baur played a sordid brute, who rules the underworld of the docks in Algiers. He remained within the exotic with his part of an Arabian sheikh in West Africa in Les secrets de la Mer Rouge/Secrets of the Red Sea (Richard Pottier, 1937).

Mollenard/Hatred (Robert Siodmak, 1938) was set in Shanghai but shot at Dunkerque, with the help of set designer Alexandre Trauner. Mollenard was one of the finest films of the era and meant another memorable part for Baur. Young Robert Lynen again played his son. Director Siodmak faced many problems during the making of this film: he lost good money over competition with Duvivier on the adaptation rights, he had trouble finding producers, and at the start of shooting Baur had a heart attack, though without consequences. La tragédie impériale/Rasputin (Marcel L'Herbier, 1938) was about the life of Rasputin and his power during the reign of the last Tsar Nicolas II. Baur had made considerable study of his character; he also wore false high heels in his shoes and lost considerable weight to look more like his character.

French postcard by Eclair Journal, no. 570. Photo: Mega Film Harry Baur as a submarine commander in Nitchevo (Jacques de Baroncelli, 1936). Eclair Journal was the distributor of the film.

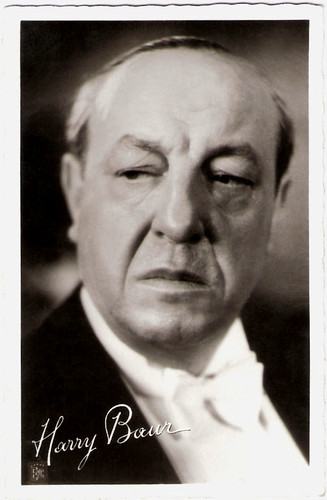

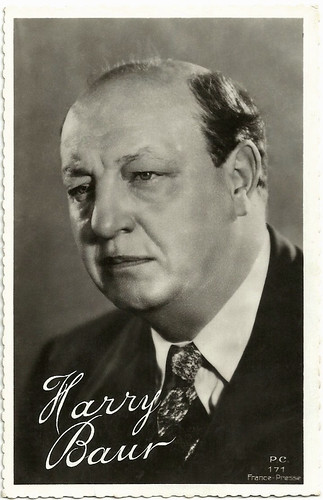

French postcard by P.C., no. 171. Photo: France Presse.

French card.

French postcard by Greff Editions, Paris, no. 21. Photo: Studio Harcourt.

Criticised by the right-wing anti-semitic press

While during the mid-1930s Harry Baur had been extremely active, in 1938 he did less, perhaps warned by his attack. That year he completed his cycle of ‘Russian’ films with Maurice Tourneur’s Le patriote/The Mad Emperor (1938), about the last days of the mad Tsar Paul I. Ten years earlier, Ernst Lubitsch had done a silent version with Emil Jannings in the lead, The Patriot (1928), which had won an Academy Award for Best Scenario. In March-April 1939 the exteriors for Jacques de Baroncelli’s film L’homme du Niger/Forbidden Love (1940) were shot in Sudan, under great difficulty. The film was selected for the first Cannes Film Festival of 1939, but because of the war that never took place.

Baur left Sudan to go to Casablanca where Jean Dréville waited for him to perform in Le président Haudecoeur/President Haudecoeur (1940). After that interiors were shot at the studios of Marcel Pagnol. The film came out on French screens on 11 April 1940. When France entered the Second World War most film shooting stopped temporarily. Many actors were mobilised but not all, so work could be done on the film Volpone (Maurice Tourneur, 1940), based on Ben Jonson’s classic text. The German army occupied Paris in June 1940. Film activities were slowed down but theatres reopened, so Baur went to the Théâtre du Gymnase for a reprisal of 'Jazz', directed by Pagnol.

During a large orchestrated campaign from late 1940-early 1941, Harry Baur was heavily criticised by the right-wing anti-semitic press, accusing him of being a Jew and a Freemason. As much as he could Baur explained his Christian roots. The first film produced by Continental Films, the German film company active in France during the war, was L’assassinat du père Noël/The Killing of Santa Claus (Christian Jaque, 1941). Hidden intentions were discovered in the dialogues written by Charles Spaak. Baur had a grand part in the film as père Cornusse, maker of maps of the world. His co-stars were Raymond Rouleau and Renée Faure. In 1941 Tourneur asked Baur a last time for his film Pechés de jeunesse/Sins of Youth.

Then things turned wrong when Baur went to Germany to play the male lead in Symphonie eines Lebens/Symphony of Life (Heinz Bertram, 1942), costarring Henny Porten. The shooting took place from February to May 1942. In the meantime, the French slander of Baur being a Jew reached Goebbels as well and in May 1942 Baur and his second wife were arrested. Baur was questioned, tortured and imprisoned. In September 1942 he was released, weighing just 40 kilos instead of around 100. He never recovered from his torture and died on 8 April 1943 in Paris.

Baur’s funeral took place at the church of St. Philippe du Roule and attracted the 'Tout-Paris' of screen and stage. He was buried at the cimetière Saint-Vincent in Montmartre, where his tomb still attracts visitors. Baur’s wife Rika Radifé survived the German maltreatment. In 1953 she took over the Theatre des Maturins in Paris and ran it for decades.

French postcard, no. 194. Photo: Studio Harcourt.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. A 1027/1, 1937-1938. Photo: Intran-Studio, Paris.

German postcard by Film-Foto-Verlag, no. A 3451/1, 1941-1944. Photo: Tobis Star-Foto-Atelier.

French postcard by Editions et publications cinematographiques, no. 82. Photo: Roger Forster.

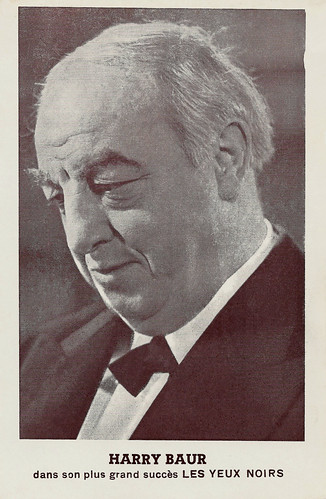

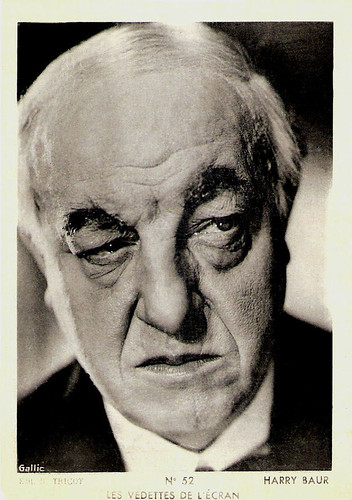

French collectors card by Editions Tricot in the series Les Vedettes de l'écran. Photo: Gallic.

Sources: Filmportal.de, cinememorial, Cinetom (now defunct), Wikipedia (French, German and English), and IMDb. CineTom has the most extensive biography, based on Hervé le Boterf’s published biography 'Harry Baur'

I highly enjoyed all of these film festival posts. I'd never heard of this festival before, but it is a wonderful idea to explore the cinematic past in this way.

ReplyDeleteHi Bunchie, Thanks. We actually were in Bologna at the Cinema Ritrovato festival. Maybe you should plan your holiday trip next year to this festival. The films are excellent, but the wine and gelato too.

ReplyDelete