On the final day of Il Cinema Ritrovato 2024, we return to 'Marlene Dietrich: Cinema Disrupted', curated by the Deutsche Kinemathek. In this second post, EFSP focuses on her sound films. Throughout her long career, Marlene Dietrich constantly re-invented herself. In the 1930s, she became a Hollywood star, then a World War II frontline entertainer, and finally she was an international stage show performer from the 1950s till the 1970s. In Hollywood, Dietrich did not shy away from disrupting film and society. She was provocative as a working mother, as a bisexual star who practised cross-dressing, as a fashion and style icon who created her own image, as an actress who intervened politically and took a clear stand for freedom, tolerance and democracy.

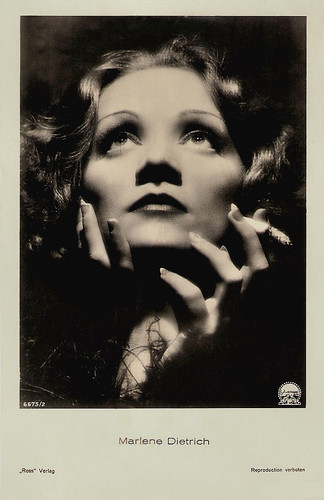

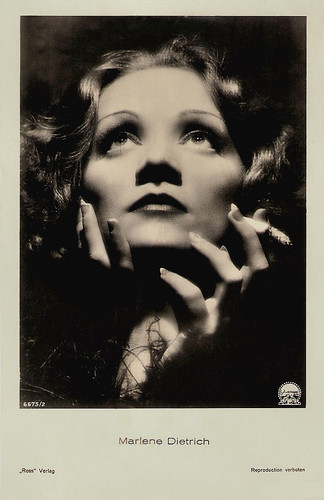

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 6673/2, 1931-1932. Photo: Don English / Paramount. Publicity still for Shanghai Express (Josef von Sternberg, 1932).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 5582/5, 1930-1931 Photo: Paramount. Marlene Dietrich in Morocco (Josef von Sternberg, 1930).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 5968/1, 1930-1931. Photo: Paramount. Marlene Dietrich in Dishonored/Agent X27 (Josef von Sternberg, 1931).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 7021/1, 1932-1933. Photo: Paramount. Marlene Dietrich in Blonde Venus (Josef von Sternberg, 1932).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 7789/2, 1932-1933. Photo: Paramount. Marlene Dietrich in The Song of Songs (Rouben Mamoulian, 1933).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 8709/1, 1933-1934. Photo: Paramount. Publicity still for The Scarlet Empress (Josef von Sternberg, 1934) with Gavin Gordon.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 8995/1, 1933-1934. Photo: Paramount. Publicity still for The Devil Is a Woman (Josef von Sternberg, 1935).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 9437/2, 1935-1936. Photo: Paramount. Marlene Dietrich in Desire (Frank Borzage, 1936).

On the strength of the success of Der blaue Engel/The Blue Angel (Josef von Sternberg, 1930), and with encouragement and promotion from her director Josef von Sternberg, Marlene Dietrich moved in February 1930 to Hollywood. She left her husband Rudi and daughter Maria behind in Berlin. Paramount wanted to market her as a German answer to MGM's Swedish sensation Greta Garbo. Von Sternberg welcomed her with gifts, including a green Rolls-Royce Phantom II. The car later appeared in their first American film Morocco.

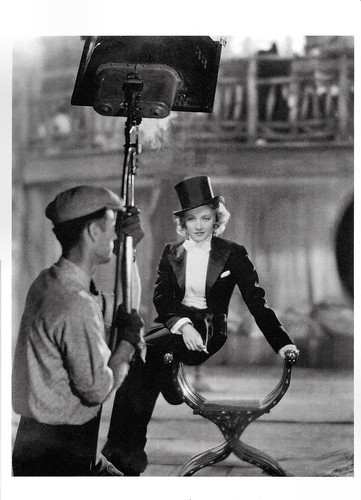

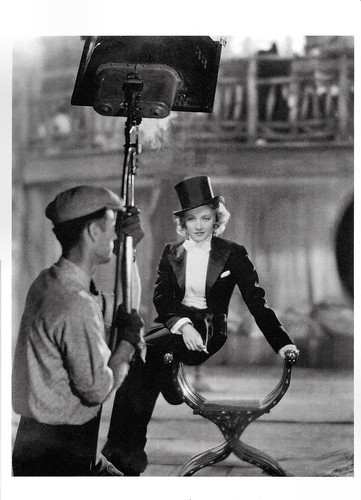

Dietrich starred in six films directed by Josef von Sternberg at Paramount between 1930 and 1935. Von Sternberg worked effectively with Dietrich to create the image of a glamorous and mysterious femme fatale. Wikipedia: "He encouraged her to lose weight and coached her intensively as an actress – she, in turn, was willing to trust him and follow his sometimes imperious direction in a way that a number of other performers resisted." In Morocco (Josef von Sternberg, 1930) with Gary Cooper, Dietrich was again cast as a cabaret singer. The film is best remembered for the sequence in which she performs a song dressed in a man's white tie and kisses another woman, both provocative for the era. The film earned Dietrich her only Academy Award nomination.

Morocco was followed by Dishonored (Josef von Sternberg, 1931), a major success. Dietrich played a Mata Hari-like spy who betrays her country for love of a worthless man (Victor McLaglen). Then followed Shanghai Express (Josef von Sternberg, 1932) with Anna May Wong. In this melodrama, Dietrich is a China Coast prostitute who offers herself to a warlord (Warner Oland) to save the life of a former lover (Clive Brook). A crucial part of the overall effect of the film was created by von Sternberg's exceptional skill in lighting and photographing Dietrich to optimum effect. In Shanghai Express he masterly uses light and shadow, including the impact of light passed through a veil or slatted blinds. Shanghai Express was dubbed by the critics 'Grand Hotel on wheels' and was another major success. The film earned $1.5 million in worldwide rentals.

Dietrich and von Sternberg again collaborated on the romance Blonde Venus (Josef von Sternberg, 1932) with Cary Grant and little Dickie Moore. Dietrich worked without von Sternberg for the first time in three years in the romantic drama Song of Songs (1933), playing a naïve German peasant, under the direction of Rouben Mamoulian. Then followed The Scarlet Empress (Josef von Sternberg, 1934) with John Lodge, an opulent and visually stunning melodrama about a lascivious Catherine the Great.

Dietrich and Sternberg's last film, The Devil Is a Woman (Josef von Sternberg, 1935) is also the most stylized of their collaborations. It is an erotic tale about a soldier-corrupting vamp in turn-of-the-century Seville. Dietrich later remarked that she was at her most beautiful in The Devil Is a Woman and that the film was her particular favourite. But after the dismal failure of The Devil Is A Woman at the box office, Paramount fired Von Sternberg. The star and director would never work together again.

Small German card by Ross Verlag for Hänsom Cigaretten by Jasmatzi Cigaretten-Fabrik G.m.b.H., Dresden, Tonfilmseries, no. 358. Photo: Eugene Robert Richee / Paramount. Marlene Dietrich in Morocco (Josef von Sternberg, 1930).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 5126/1, 1930-1931. Photo: Eugene Robert Richee / Paramount. Marlene Dietrich in Morocco (Josef von Sternberg, 1930). Collection: Marlene Pilaete.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 5964/3, 1930-1931. Photo: Paramount. Marlene Dietrich in Dishonored/Agent X27 (Josef von Sternberg, 1931). Collection: Geoffrey Donaldson Institute.

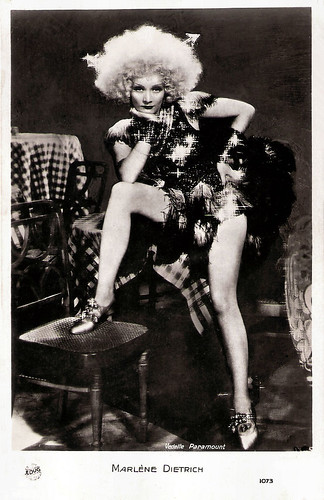

French postcard by EDUG, no. 1073. Photo: Paramount. Publicity still for Blonde Venus (Josef von Sternberg, 1932).

French postcard by Europe, no. 58. Photo: Paramount. Publicity still for Shanghai Express (Josef von Sternberg, 1932).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 8852/2, 1933-1934. Photo: William Walling Jr. / Paramount. Marlene Dietrich in Shanghai Express (Josef von Sternberg, 1932).

Dutch postcard, no. 294. Photo: Paramount.

Dutch postcard, no. 326. Sent by mail in the Netherlands in 1934. Photo: Paramount. Publicity still for Shanghai Express (Josef von Sternberg, 1932).

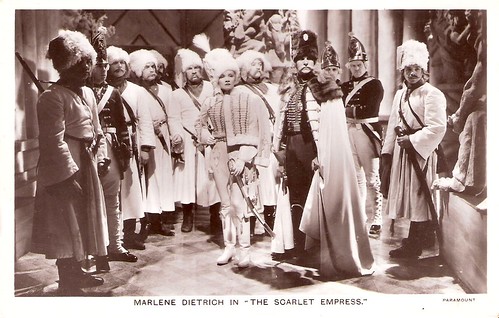

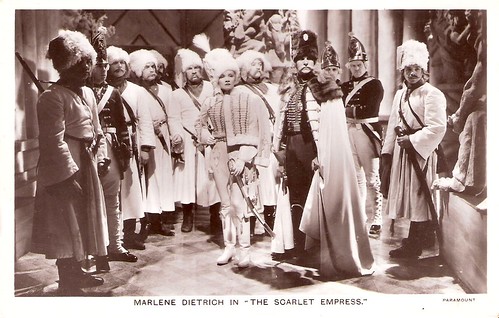

British postcard by Film-Kurier Series, London, no. 19. Photo: Paramount Pictures. Publicity still for The Scarlet Empress (Josef von Sternberg, 1934).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 9640/1, 1935-1936. Photo: Paramount. Marlene Dietrich and Gary Cooper in Desire (Frank Borzage, 1936).

Without Von Sternberg, Marlene Dietrich made her first comedy, Desire (Frank Borzage, 1936). It was a satire about an urbane jewel thief (Dietrich) who steals a choice necklace from a Parisian jeweller and, in efforts to keep it, becomes involved with a hayseed Detroit engineer (Gary Cooper). The film was a commercial success that gave Dietrich an opportunity to try her hand at romantic comedy. Her next project, I Loved a Soldier (1936), ended in shambles when the film was scrapped several weeks into production due to script problems, scheduling confusion and the studio's decision to fire the producer Ernst Lubitsch.

Extravagant offers lured Dietrich away from Paramount to make her first colour film The Garden of Allah (Richard Boleslawski, 1936) for independent producer David O. Selznick, for which she received $200,000, and to Britain for Alexander Korda's production, Knight Without Armour (Jacques Feyder, 1937), at a salary of $450,000, which made her one of the best paid film stars of the time. Although Dietrich's salary in the mid 1930s was enormous, she was never listed among the top ten box-office attractions, and depression-era audiences often felt she was preposterously exotic. She was even labelled 'box office poison' after Knight Without Armour proved an expensive flop.

While in London, Dietrich later said in interviews, she was approached by Nazi Party officials and offered lucrative contracts, should she agree to return to be a foremost film star in Nazi Germany. She refused their offers and applied for U.S. citizenship in 1937. She returned to Paramount to make Angel (1937), another romantic comedy directed by Ernst Lubitsch. The film was poorly received, leading Paramount to buy out the remainder of Dietrich's contract. In 1939, her stardom revived when she played the freewheeling saloon entertainer Frenchie in the comic Western Destry Rides Again (George Marshall, 1939) opposite James Stewart. Hollywood's attempt to make her more 'ordinary' worked. The film also introduced another favourite song, 'The Boys in the Back Room'. She played a similar role with John Wayne and Randolph Scott in The Spoilers (Ray Enright, 1942).

Dietrich was known to have strong political convictions and the mind to speak them. In the late 1930s, Dietrich created a fund with Billy Wilder and several other exiles to help Jews and dissidents escape from Germany. In 1937, her entire salary for Knight Without Armor ($450,000) was put into escrow to help the refugees. In 1939, she became an American citizen and renounced her German citizenship. In December 1941, the US entered World War II, and Dietrich became one of the first celebrities to raise war bonds. She toured the US from January 1942 to September 1943 and it is said that she sold more war bonds than any other star. During two extended tours for the USO in 1944 and 1945, she sang and performed the singing saw for Allied troops on the front lines in Algeria, Italy, England and France.

Her revue, with Danny Thomas as her opening act for the first tour, included songs from her films, performances on her musical saw and a 'mindreading' act that her friend Orson Welles had taught her for his Mercury Wonder Show. Dietrich would inform the audience that she could read minds and ask them to concentrate on whatever came into their minds. Then she would walk over to a soldier and earnestly tell him, "Oh, think of something else. I can't possibly talk about that!" American church papers reportedly published stories complaining about this part of Dietrich's act. For musical propaganda broadcasts designed to demoralize enemy soldiers, she recorded a number of songs in German, including the ballad 'Lili Marleen'. The troops loved her. In 1947, she was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by the US for her wartime work. In 1950, the French state conferred the title of 'Chevalier de la Légion d' Honneur' (Knight of the Legion of Honour) on her, in 1971 she was named 'Officier' by President Pompidou and in 1989 'Commandeur' by President Mitterrand.

British postcard, no. 34. Photo: Paramount Pictures. Marlene Dietrich in The Song of Songs (Rouben Mamoulian, 1932), based on 'Das hohe Lied' by German author Hermann Sudermann.

British postcard, distributed in the Netherlands by M. Bonnist & Zonen, Amsterdam, no. 136e. Photo: Paramount. Publicity still for Blonde Venus (Josef von Sternberg, 1932) with Dickie Moore.

British-Dutch postcard by M. Bonnist & Zonen, Amsterdam, no. B 351. Photo: Paramount. Publicity still for The Scarlet Empress (Josef von Sternberg, 1934) with Marlene Dietrich as Catherine the Great, the notorious empress of Russia.

French postcard in Cinémagazine-Edition, no. 60. Photo: Don English / Paramount. Marlene Dietrich in The Devil Is a Woman (Josef von Sternberg, 1935). Costume: Travis Banton.

French postcard by Editions Chantal, Rueil, no. 3. Photo: London Film Productions. Publicity still for Knight Without Armour (Jacques Feyder, 1937).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 9906/4, 1935-1936. Photo: London Film Productions. Marlene Dietrich in Knight Without Armour (Jacques Feyder, 1937).

Italian postcard by Rizzoli & c., Milano, 1938 XVI Photo: Korda Films. Marlene Dietrich in Knight Without Armour (Jacques Feyder, 1937).

British postcard by Art Photo Postcard, no. 125. Marlene Dietrich and Robert Donat in the London Films production Knight Without Armour (Jacques Feyder, 1937).

Dutch postcard by M. Bonnist & Zonen, Amsterdam, no. B 480. Photo: Paramount. Herbert Marshall and Marlene Dietrich in Angel (Ernst Lubitsch, 1937). Collection: Marlene Pilaete.

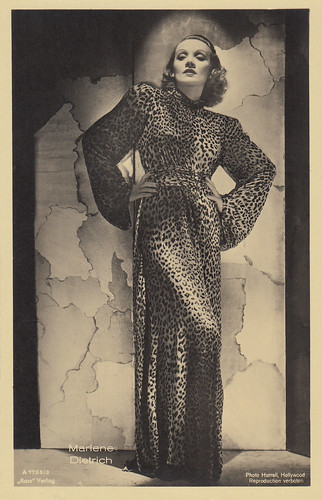

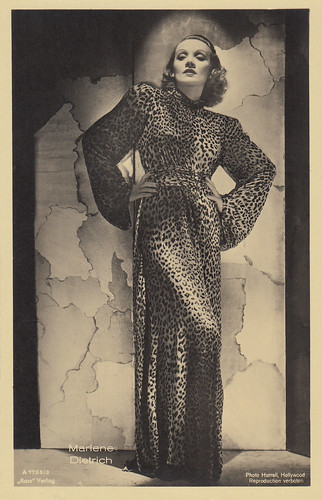

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. A 1755/3, 1937-1938. Photo: George Hurrell, Hollywood. Collection: Marlene Pilaete.

From the early 1950s until the mid-1970s, Marlene Dietrich worked almost exclusively as a highly-paid cabaret artist, performing live in large theatres in major cities worldwide. Dietrich employed Burt Bacharach as her musical arranger starting in the mid-1950s. Together, they refined her nightclub act into a more ambitious theatrical one-woman show with an expanded repertoire. Her repertoire included songs from her films as well as popular songs of the day. Her costumes (body-hugging dresses covered with thousands of crystals as well as a swansdown coat), body-sculpting undergarments, careful stage lighting helped to preserve Dietrich's glamorous image well into old age.

She never fully regained her former screen glory, but she continued performing in films for distinguished directors. Her successful film roles included an exotic gypsy in Golden Earrings (Mitchell Leisen, 1947), with Ray Milland, an ex-Nazi cafe singer in A Foreign Affair (Billy Wilder, 1948), a famous singer and murderer in Stage Fright (Alfred Hitchcock, 1950), an ageing bandit queen in Rancho Notorious (Fritz Lang, 1952), the wife of a suspected murderer in Witness for the Prosecution (Billy Wilder, 1957), a cynical brothel-keeper in Touch of Evil (Orson Welles, 1958), and the aristocratic widow of a prominent Nazi general in Judgment at Nuremberg (Stanley Kramer, 1961).

Dietrich's show business career largely ended in 1975, when she broke her leg during a stage performance in Sydney, Australia. Her husband, Rudolf Sieber, died of cancer in 1976. Her final on-camera film appearance was a small role in Schöner Gigolo, armer Gigolo/Just a Gigolo (David Hemmings, 1979), starring David Bowie. Dietrich withdrew to her apartment in Paris. She spent the final 11 years of her life mostly bedridden, allowing only a select few — including family and employees — to enter the apartment. During this time, she was a prolific letter-writer and phone-caller. Her autobiography, 'Nehmt nur mein Leben/Marlene', was published in 1979.

In 1982, she agreed to participate in a documentary film about her life, Marlene (1984), but refused to be filmed. The film's director, Maximilian Schell, was only allowed to record her voice. He used his interviews with her as the basis for the film, set to a collage of film clips from her career. The final film won several European film prizes and received an Academy Award nomination for Best Documentary in 1984. Newsweek named it "a unique film, perhaps the most fascinating and affecting documentary ever made about a great movie star". Her autobiography, 'Ich bin, Gott sei Dank, Berlinerin' (I Am, Thank God, a Berliner) or 'Marlene', was published in 1987.

In 1992, Marlene Dietrich died of renal failure at the age of 90 in Paris. In an obituary The New York Times concluded: "In her films and record-breaking cabaret performances, Miss Dietrich artfully projected cool sophistication, self-mockery and infinite experience. Her sexuality was audacious, her wit was insolent and her manner was ageless. With a world-weary charm and a diaphanous gown showing off her celebrated legs, she was the quintessential cabaret entertainer of Weimar-era Germany." Eight years after her death, a collection of her film costumes, recordings, written documents, photographs, and other personal items was put on permanent display in the Berlin Film Museum (2000). Two years later, Berlin - the city of Dietrich's birth which she shunned for most of her life - declared her an honorary citizen.

Big German card by Ross Verlag. Photo: Paramount.

French postcard by Editions P.I., no. 219.

British postcard in the Picturegoer series, London, no. W 340. Photo: Paramount.

Spanish postcard. Photo: Ray Jones, Universal, 1939.

Belgian collectors card by Kwatta, Bois d'Haine, no. C 156. Photo: M.G.M. Publicity still for Kismet (William Dieterle, 1944) with Ronald Colman.

Belgian press photo by BRT Television. Jean Arthur, John Lund and Marlene Dietrich in A Foreign Affair (Billy Wilder, 1948).

West German postcard by Kunst und Bild, Berlin / Crazy Cards, Berlin. Photo: RKO Radio Film. Marlene Dietrich in Rancho Notorious (Fritz Lang, 1952).

West-German postcard by Kunst und Bild, Berlin / Crazy Cards, Berlin. Photo: RKO Radio Film. Marlene Dietrich in Rancho Notorious (Fritz Lang, 1952).

American postcard by Quantity Postcards, Oakland, no. 3372.

East-German postcard by VEB Progress Filmvertrieb, no. 2.192, 1964.

Swiss-German-British postcard by News Productions, Baulmes / Filmwelt Berlin, Bakede / News Productions, Stroud, no. 56481. Photo: Paramount, 1932 / Collection Cinémathèque Suisse, Lausanne.

American postcard by Pomegranate Publications, Petaluma, CA, no. 2160. Photo: Popprerfoto, London. Marlene Dietrich and Charles Boyer in Garden of Allah (Richard Boleslawski, 1936).

Sources: James Naremore (Senses of Cinema), Wikipedia, The New York Times, Britannica, and IMDb.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 6673/2, 1931-1932. Photo: Don English / Paramount. Publicity still for Shanghai Express (Josef von Sternberg, 1932).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 5582/5, 1930-1931 Photo: Paramount. Marlene Dietrich in Morocco (Josef von Sternberg, 1930).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 5968/1, 1930-1931. Photo: Paramount. Marlene Dietrich in Dishonored/Agent X27 (Josef von Sternberg, 1931).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 7021/1, 1932-1933. Photo: Paramount. Marlene Dietrich in Blonde Venus (Josef von Sternberg, 1932).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 7789/2, 1932-1933. Photo: Paramount. Marlene Dietrich in The Song of Songs (Rouben Mamoulian, 1933).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 8709/1, 1933-1934. Photo: Paramount. Publicity still for The Scarlet Empress (Josef von Sternberg, 1934) with Gavin Gordon.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 8995/1, 1933-1934. Photo: Paramount. Publicity still for The Devil Is a Woman (Josef von Sternberg, 1935).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 9437/2, 1935-1936. Photo: Paramount. Marlene Dietrich in Desire (Frank Borzage, 1936).

Josef von Sternberg

On the strength of the success of Der blaue Engel/The Blue Angel (Josef von Sternberg, 1930), and with encouragement and promotion from her director Josef von Sternberg, Marlene Dietrich moved in February 1930 to Hollywood. She left her husband Rudi and daughter Maria behind in Berlin. Paramount wanted to market her as a German answer to MGM's Swedish sensation Greta Garbo. Von Sternberg welcomed her with gifts, including a green Rolls-Royce Phantom II. The car later appeared in their first American film Morocco.

Dietrich starred in six films directed by Josef von Sternberg at Paramount between 1930 and 1935. Von Sternberg worked effectively with Dietrich to create the image of a glamorous and mysterious femme fatale. Wikipedia: "He encouraged her to lose weight and coached her intensively as an actress – she, in turn, was willing to trust him and follow his sometimes imperious direction in a way that a number of other performers resisted." In Morocco (Josef von Sternberg, 1930) with Gary Cooper, Dietrich was again cast as a cabaret singer. The film is best remembered for the sequence in which she performs a song dressed in a man's white tie and kisses another woman, both provocative for the era. The film earned Dietrich her only Academy Award nomination.

Morocco was followed by Dishonored (Josef von Sternberg, 1931), a major success. Dietrich played a Mata Hari-like spy who betrays her country for love of a worthless man (Victor McLaglen). Then followed Shanghai Express (Josef von Sternberg, 1932) with Anna May Wong. In this melodrama, Dietrich is a China Coast prostitute who offers herself to a warlord (Warner Oland) to save the life of a former lover (Clive Brook). A crucial part of the overall effect of the film was created by von Sternberg's exceptional skill in lighting and photographing Dietrich to optimum effect. In Shanghai Express he masterly uses light and shadow, including the impact of light passed through a veil or slatted blinds. Shanghai Express was dubbed by the critics 'Grand Hotel on wheels' and was another major success. The film earned $1.5 million in worldwide rentals.

Dietrich and von Sternberg again collaborated on the romance Blonde Venus (Josef von Sternberg, 1932) with Cary Grant and little Dickie Moore. Dietrich worked without von Sternberg for the first time in three years in the romantic drama Song of Songs (1933), playing a naïve German peasant, under the direction of Rouben Mamoulian. Then followed The Scarlet Empress (Josef von Sternberg, 1934) with John Lodge, an opulent and visually stunning melodrama about a lascivious Catherine the Great.

Dietrich and Sternberg's last film, The Devil Is a Woman (Josef von Sternberg, 1935) is also the most stylized of their collaborations. It is an erotic tale about a soldier-corrupting vamp in turn-of-the-century Seville. Dietrich later remarked that she was at her most beautiful in The Devil Is a Woman and that the film was her particular favourite. But after the dismal failure of The Devil Is A Woman at the box office, Paramount fired Von Sternberg. The star and director would never work together again.

Small German card by Ross Verlag for Hänsom Cigaretten by Jasmatzi Cigaretten-Fabrik G.m.b.H., Dresden, Tonfilmseries, no. 358. Photo: Eugene Robert Richee / Paramount. Marlene Dietrich in Morocco (Josef von Sternberg, 1930).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 5126/1, 1930-1931. Photo: Eugene Robert Richee / Paramount. Marlene Dietrich in Morocco (Josef von Sternberg, 1930). Collection: Marlene Pilaete.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 5964/3, 1930-1931. Photo: Paramount. Marlene Dietrich in Dishonored/Agent X27 (Josef von Sternberg, 1931). Collection: Geoffrey Donaldson Institute.

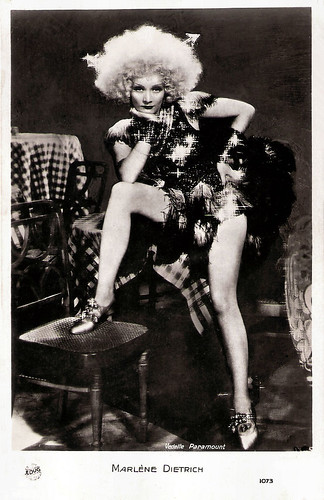

French postcard by EDUG, no. 1073. Photo: Paramount. Publicity still for Blonde Venus (Josef von Sternberg, 1932).

French postcard by Europe, no. 58. Photo: Paramount. Publicity still for Shanghai Express (Josef von Sternberg, 1932).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 8852/2, 1933-1934. Photo: William Walling Jr. / Paramount. Marlene Dietrich in Shanghai Express (Josef von Sternberg, 1932).

Dutch postcard, no. 294. Photo: Paramount.

Dutch postcard, no. 326. Sent by mail in the Netherlands in 1934. Photo: Paramount. Publicity still for Shanghai Express (Josef von Sternberg, 1932).

British postcard by Film-Kurier Series, London, no. 19. Photo: Paramount Pictures. Publicity still for The Scarlet Empress (Josef von Sternberg, 1934).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 9640/1, 1935-1936. Photo: Paramount. Marlene Dietrich and Gary Cooper in Desire (Frank Borzage, 1936).

Box office poison

Without Von Sternberg, Marlene Dietrich made her first comedy, Desire (Frank Borzage, 1936). It was a satire about an urbane jewel thief (Dietrich) who steals a choice necklace from a Parisian jeweller and, in efforts to keep it, becomes involved with a hayseed Detroit engineer (Gary Cooper). The film was a commercial success that gave Dietrich an opportunity to try her hand at romantic comedy. Her next project, I Loved a Soldier (1936), ended in shambles when the film was scrapped several weeks into production due to script problems, scheduling confusion and the studio's decision to fire the producer Ernst Lubitsch.

Extravagant offers lured Dietrich away from Paramount to make her first colour film The Garden of Allah (Richard Boleslawski, 1936) for independent producer David O. Selznick, for which she received $200,000, and to Britain for Alexander Korda's production, Knight Without Armour (Jacques Feyder, 1937), at a salary of $450,000, which made her one of the best paid film stars of the time. Although Dietrich's salary in the mid 1930s was enormous, she was never listed among the top ten box-office attractions, and depression-era audiences often felt she was preposterously exotic. She was even labelled 'box office poison' after Knight Without Armour proved an expensive flop.

While in London, Dietrich later said in interviews, she was approached by Nazi Party officials and offered lucrative contracts, should she agree to return to be a foremost film star in Nazi Germany. She refused their offers and applied for U.S. citizenship in 1937. She returned to Paramount to make Angel (1937), another romantic comedy directed by Ernst Lubitsch. The film was poorly received, leading Paramount to buy out the remainder of Dietrich's contract. In 1939, her stardom revived when she played the freewheeling saloon entertainer Frenchie in the comic Western Destry Rides Again (George Marshall, 1939) opposite James Stewart. Hollywood's attempt to make her more 'ordinary' worked. The film also introduced another favourite song, 'The Boys in the Back Room'. She played a similar role with John Wayne and Randolph Scott in The Spoilers (Ray Enright, 1942).

Dietrich was known to have strong political convictions and the mind to speak them. In the late 1930s, Dietrich created a fund with Billy Wilder and several other exiles to help Jews and dissidents escape from Germany. In 1937, her entire salary for Knight Without Armor ($450,000) was put into escrow to help the refugees. In 1939, she became an American citizen and renounced her German citizenship. In December 1941, the US entered World War II, and Dietrich became one of the first celebrities to raise war bonds. She toured the US from January 1942 to September 1943 and it is said that she sold more war bonds than any other star. During two extended tours for the USO in 1944 and 1945, she sang and performed the singing saw for Allied troops on the front lines in Algeria, Italy, England and France.

Her revue, with Danny Thomas as her opening act for the first tour, included songs from her films, performances on her musical saw and a 'mindreading' act that her friend Orson Welles had taught her for his Mercury Wonder Show. Dietrich would inform the audience that she could read minds and ask them to concentrate on whatever came into their minds. Then she would walk over to a soldier and earnestly tell him, "Oh, think of something else. I can't possibly talk about that!" American church papers reportedly published stories complaining about this part of Dietrich's act. For musical propaganda broadcasts designed to demoralize enemy soldiers, she recorded a number of songs in German, including the ballad 'Lili Marleen'. The troops loved her. In 1947, she was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by the US for her wartime work. In 1950, the French state conferred the title of 'Chevalier de la Légion d' Honneur' (Knight of the Legion of Honour) on her, in 1971 she was named 'Officier' by President Pompidou and in 1989 'Commandeur' by President Mitterrand.

British postcard, no. 34. Photo: Paramount Pictures. Marlene Dietrich in The Song of Songs (Rouben Mamoulian, 1932), based on 'Das hohe Lied' by German author Hermann Sudermann.

British postcard, distributed in the Netherlands by M. Bonnist & Zonen, Amsterdam, no. 136e. Photo: Paramount. Publicity still for Blonde Venus (Josef von Sternberg, 1932) with Dickie Moore.

British-Dutch postcard by M. Bonnist & Zonen, Amsterdam, no. B 351. Photo: Paramount. Publicity still for The Scarlet Empress (Josef von Sternberg, 1934) with Marlene Dietrich as Catherine the Great, the notorious empress of Russia.

French postcard in Cinémagazine-Edition, no. 60. Photo: Don English / Paramount. Marlene Dietrich in The Devil Is a Woman (Josef von Sternberg, 1935). Costume: Travis Banton.

French postcard by Editions Chantal, Rueil, no. 3. Photo: London Film Productions. Publicity still for Knight Without Armour (Jacques Feyder, 1937).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 9906/4, 1935-1936. Photo: London Film Productions. Marlene Dietrich in Knight Without Armour (Jacques Feyder, 1937).

Italian postcard by Rizzoli & c., Milano, 1938 XVI Photo: Korda Films. Marlene Dietrich in Knight Without Armour (Jacques Feyder, 1937).

British postcard by Art Photo Postcard, no. 125. Marlene Dietrich and Robert Donat in the London Films production Knight Without Armour (Jacques Feyder, 1937).

Dutch postcard by M. Bonnist & Zonen, Amsterdam, no. B 480. Photo: Paramount. Herbert Marshall and Marlene Dietrich in Angel (Ernst Lubitsch, 1937). Collection: Marlene Pilaete.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. A 1755/3, 1937-1938. Photo: George Hurrell, Hollywood. Collection: Marlene Pilaete.

Body-hugging dresses and careful stage lighting

From the early 1950s until the mid-1970s, Marlene Dietrich worked almost exclusively as a highly-paid cabaret artist, performing live in large theatres in major cities worldwide. Dietrich employed Burt Bacharach as her musical arranger starting in the mid-1950s. Together, they refined her nightclub act into a more ambitious theatrical one-woman show with an expanded repertoire. Her repertoire included songs from her films as well as popular songs of the day. Her costumes (body-hugging dresses covered with thousands of crystals as well as a swansdown coat), body-sculpting undergarments, careful stage lighting helped to preserve Dietrich's glamorous image well into old age.

She never fully regained her former screen glory, but she continued performing in films for distinguished directors. Her successful film roles included an exotic gypsy in Golden Earrings (Mitchell Leisen, 1947), with Ray Milland, an ex-Nazi cafe singer in A Foreign Affair (Billy Wilder, 1948), a famous singer and murderer in Stage Fright (Alfred Hitchcock, 1950), an ageing bandit queen in Rancho Notorious (Fritz Lang, 1952), the wife of a suspected murderer in Witness for the Prosecution (Billy Wilder, 1957), a cynical brothel-keeper in Touch of Evil (Orson Welles, 1958), and the aristocratic widow of a prominent Nazi general in Judgment at Nuremberg (Stanley Kramer, 1961).

Dietrich's show business career largely ended in 1975, when she broke her leg during a stage performance in Sydney, Australia. Her husband, Rudolf Sieber, died of cancer in 1976. Her final on-camera film appearance was a small role in Schöner Gigolo, armer Gigolo/Just a Gigolo (David Hemmings, 1979), starring David Bowie. Dietrich withdrew to her apartment in Paris. She spent the final 11 years of her life mostly bedridden, allowing only a select few — including family and employees — to enter the apartment. During this time, she was a prolific letter-writer and phone-caller. Her autobiography, 'Nehmt nur mein Leben/Marlene', was published in 1979.

In 1982, she agreed to participate in a documentary film about her life, Marlene (1984), but refused to be filmed. The film's director, Maximilian Schell, was only allowed to record her voice. He used his interviews with her as the basis for the film, set to a collage of film clips from her career. The final film won several European film prizes and received an Academy Award nomination for Best Documentary in 1984. Newsweek named it "a unique film, perhaps the most fascinating and affecting documentary ever made about a great movie star". Her autobiography, 'Ich bin, Gott sei Dank, Berlinerin' (I Am, Thank God, a Berliner) or 'Marlene', was published in 1987.

In 1992, Marlene Dietrich died of renal failure at the age of 90 in Paris. In an obituary The New York Times concluded: "In her films and record-breaking cabaret performances, Miss Dietrich artfully projected cool sophistication, self-mockery and infinite experience. Her sexuality was audacious, her wit was insolent and her manner was ageless. With a world-weary charm and a diaphanous gown showing off her celebrated legs, she was the quintessential cabaret entertainer of Weimar-era Germany." Eight years after her death, a collection of her film costumes, recordings, written documents, photographs, and other personal items was put on permanent display in the Berlin Film Museum (2000). Two years later, Berlin - the city of Dietrich's birth which she shunned for most of her life - declared her an honorary citizen.

Big German card by Ross Verlag. Photo: Paramount.

French postcard by Editions P.I., no. 219.

British postcard in the Picturegoer series, London, no. W 340. Photo: Paramount.

Spanish postcard. Photo: Ray Jones, Universal, 1939.

Belgian collectors card by Kwatta, Bois d'Haine, no. C 156. Photo: M.G.M. Publicity still for Kismet (William Dieterle, 1944) with Ronald Colman.

Belgian press photo by BRT Television. Jean Arthur, John Lund and Marlene Dietrich in A Foreign Affair (Billy Wilder, 1948).

West German postcard by Kunst und Bild, Berlin / Crazy Cards, Berlin. Photo: RKO Radio Film. Marlene Dietrich in Rancho Notorious (Fritz Lang, 1952).

West-German postcard by Kunst und Bild, Berlin / Crazy Cards, Berlin. Photo: RKO Radio Film. Marlene Dietrich in Rancho Notorious (Fritz Lang, 1952).

American postcard by Quantity Postcards, Oakland, no. 3372.

East-German postcard by VEB Progress Filmvertrieb, no. 2.192, 1964.

Swiss-German-British postcard by News Productions, Baulmes / Filmwelt Berlin, Bakede / News Productions, Stroud, no. 56481. Photo: Paramount, 1932 / Collection Cinémathèque Suisse, Lausanne.

American postcard by Pomegranate Publications, Petaluma, CA, no. 2160. Photo: Popprerfoto, London. Marlene Dietrich and Charles Boyer in Garden of Allah (Richard Boleslawski, 1936).

Sources: James Naremore (Senses of Cinema), Wikipedia, The New York Times, Britannica, and IMDb.

No comments:

Post a Comment