Vitagraph, also known as the American Vitagraph Company, was a pioneering film studio, active during the silent era. It was founded in 1897 in Brooklyn by two British immigrants, J. Stuart Blackton and Albert E. Smith. Their company prospered thanks to the filming of some major historical events around the turn of the century. In 1906, Vitagraph opened a modern, glass-enclosed studio in New York, and became the most prolific American film production company, producing many well-known early silent films. The studio made countless contributions to the history of film-making, and created the first American film star, Florence Turner ‘the Vitagraph Girl’, the first Matinee Idol Maurice Costello and the most popular film comedian before Chaplin, John Bunny. But Vitagraph was to slow with starting to make feature films and in 1925, it was bought by Warner Bros.

American postcard by The Ess an Ess Photo Co., New York. Photo: Vitagraph. Caption: Florence E. Turner, Vitagraph Players.

British postcard. Editor unknown. Caption: Maurice Costello, of the Vitagraph Players.

John Bunny. British or American postcard. Editor unknown.

British postcard. Editor unknown. Caption: Flora Finch, of the Vitagraph Players.

British postcard. Editor unknown. Caption: Lilian Walker, of the Vitagraph Players.

In 1896, English émigré J. Stuart Blackton worked for the New York Evening World when he was sent to interview Thomas Edison about his new film projector. The inventor talked the entrepreneurial reporter into buying a set of films and a projector. A year later, Blackton and business partner Albert E. Smith founded the American Vitagraph Company in direct competition with Edison. Vitagraph made its debut at Tony Pastor's New Fourteenth Street Theatre on 23 March 1896, with fellow Brit Ronald Reader as projectionist. Blackton and Smith performed vaudeville acts, but with the addition of motion pictures that were typical of the day - a train coming into the station, the Niagara Falls, a man shovelling snow, a boy romping with his dog and anything else that showed movement. A third partner, distributor William ‘Pop’ Rock, joined in 1899.

The company's first studio was located on the rooftop of 140 Nassau Street in Lower Manhattan. There Blackton and Smith shot their first film, The Burglar on the Roof (1897). Tim Lussier at Silents are Golden: “The film was supposed to only involve a burglar (played by Blackton) and a policeman, however, when the ‘policeman’ began struggling with the ‘burglar,’ Mrs. Olsen, the wife of the building's janitor, came on the scene. Thinking she had happened upon the real thing, she began beating the ‘burglar’ with her broom. At first worried that their film was ruined, they were pleased to see the favorable reaction from the audience at Pastor's the next evening.” Operations were later moved to the spacious and less expensive Midwood neighbourhood of Brooklyn, New York. Vitagraph produced The Humpty Dumpty Circus (J. Stuart Blackton, 1897 or 1898), which was the first film to use the stop-motion technique. The film featured a circus with acrobats and animals in motion.

The reputation of the American Vitagraph Company was bolstered greatly by the filming of some major historical events around the turn of the century like the Spanish-American War of 1898, the Boer War in South Africa in 1900, the 1904 inauguration of President Theodore Roosevelt and the aftermath of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. When the dead from the Maine explosion were brought back to Arlington Cemetery in Washington, D.C., Vitagraph was there to film it with very successful, and emotional, results. Smith and Blackton then managed to gain passage to Cuba on the same ship that Teddy Roosevelt and his Rough Riders were on eventually accompanying him on his famous 'charge' up San Juan Hill. These shorts were among the first works of film propaganda, and a few had that most characteristic fault of propaganda, studio re-enactments being passed off as footage of actual events. The Battle of Santiago Bay (J. Stuart Blackton, 1898) was filmed in an improvised bathtub, with the ‘smoke of battle’ provided by Mrs. Blackton's cigar. It still proved believable to the filmgoers of the day and was very, very popular. The American Vitagraph Company made many contributions to the history of film-making. In 1903 the Austrian director Joseph Delmont started his career by producing Westerns, one-reel pictures lasting only a few minutes. He later became famous by using ‘wild carnivores’ in his films — a sensation for that time. In 1906, Vitagraph opened a glass-enclosed studio in New York, the first modern film studio in the U.S. Very successful proved the foreign operations of the studio and Vitagraph opened offices in London, Paris and Berlin in 1908. In 1911, they created a second film studio in Santa Monica, California, and a year later moved to a 29-acre sheep ranch in the Los Feliz district of Los Angeles, a studio subsequently owned by ABC and currently Disney Studios.

The American Vitagraph company temporarily ceased production in January 1901 due to Edison patents lawsuits. Vitagraph was not the only company seeking to make money from Edison's motion picture inventions, and Edison's lawyers were very busy in the 1890s and 1900s filing patents and suing competitors for patent infringement. The company resumed production after a distribution agreement was reached with Edison Manufacturing Company in 1902. By circa 1904, the company was again handling its own distribution. Blackton did his best to avoid lawsuits by buying a special license from Edison in 1907 and by agreeing to sell many of his most popular films to Edison for distribution. In 1909, Vitagraph was one of the original ten production companies included in Edison's attempt to corner film-making, the Motion Picture Patents Company (MPPC), a trust of all the major USA film companies and local foreign-branches (Edison, Biograph, Vitagraph, Essanay, Selig Polyscope, Lubin Manufacturing, Kalem Company, Star Film Paris, American Pathé), the leading film distributor (George Kleine) and the biggest supplier of raw film stock, Eastman Kodak. From 1911 through circa April 1915, all the product of the MPPC members was distributed by The General Film Company. MPPC ended the domination of foreign films on American screens, standardised the manner in which films were distributed and exhibited within the USA, and improved the quality of American films by internal competition. But it also discouraged its members' entry into feature film production, and the use of outside financing, both to its members' eventual detriment. Vitagraph did not release its first features until 1914, after dozens, if not hundreds, of feature films had been released by independents.

By 1909, the Vitagraph Company began to release three reels of film a week and had 30 actors and actresses and seven directors under contract, in addition to technical and business staff. Vitagraph created one of the world's first film stars, Florence Turner also known as 'the Vitagraph Girl'. She had made her film debut in How to Cure a Cold (1907). At the time there were no stars per se, unless an already famous stage star made a film. Performers were not even mentioned by name. The Vitagraph Girl became the most popular American actress to appear on screen which was at that time still dominated by French pictures, especially from the Pathé and Gaumont companies. Her worth to the studio, as its biggest box-office draw, was recognised in 1907 when her pay was upped to $22 a week, as proto-star plus part-time seamstress. Florence was paired several times with heart throb Wallace Reid, who was also on his way to stardom. In March 1910, Turner and Florence Lawrence became the first screen actors not already famous in another medium to be publicised by name by their studios to the general public. But with the rise of more stars, such as Mary Pickford at Biograph Studios, Florence Turner was no longer quite as special. By 1913 she was looking for new pastures and left the United States accompanied by director Laurence Trimble. They moved to England, where she and Trimble began performing together in London music halls and started their own film company.

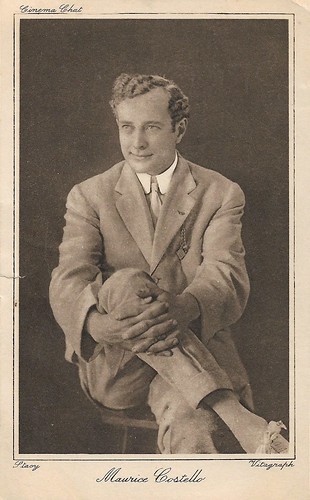

The first of the matinee idols was the super-popular Maurice Costello, who had been a prominent vaudeville actor of the late 1890s and early 1900s. In 1908, Costello joined Vitagraph, and thus also became a member of the first motion picture stock company ever formed. Among some of his best known pictures are the condensed Charles Dickens adaptation A Tale of Two Cities (William Humphrey, 1911), The Man Who Couldn't Beat God (Maurice Costello, Robert Gaillard, 1915) and For the Honor of the Family (Van Dyke Brooke, 1912) with his young daughter Dolores Costello as a child. Later, he found the transition to ‘talkies’ extremely difficult, and his leading man status was over. However, Costello was a trouper, and continued to appear in films, often in small roles and bit parts, right up until his death in 1950.

Vitagraph produced a series of William Shakespeare adaptations, the first American adaptations of the Bard's works. The series included Macbeth (James Stuart Blackton, 1908) starring William Ranous, Romeo and Juliet (James Stuart Blackton, 1908) with Paul Panzer as Romeo and Florence Lawrence as Juliet, and A Midsummer Night's Dream (Charles Kent, J. Stuart Blackton, 1909) with Maurice Costello as Lysander. Most of these short films are considered lost now. Vitagraph also was the first to film one of Mark Twain's stories, A Curious Dream (J. Stuart Blackton, 1904 or 1907), with the author's blessings. And several other Vitagraph films were centred on such well-known characters as Sherlock Holmes, Oliver Twist, Salome, Richelieu, Moses, and Saul and David.

The first animal star of the Silent Era was Jean, the Vitagraph Dog. Jean was a female Scotch Collie, owned and guided by director Laurence Trimble. From 1910 on, Jean was starring in her own short films, all directed by Trimble. One-reelers and two-reelers with titles such as Jean and the Calico Doll (Larry Trimble, 1910), Jean and the Waif (Larry Trimble, 1910) and Jean Goes Fishing (Larry Trimble, 1910) were made by Trimble as the Vitagraph troupe filmed along the coastline in his native Maine. Actress Helen Hayes played as an eight-year-old with long curls the juvenile lead in Jean and the Calico Doll (Larry Trimble, 1910). Trimble became a leading director at Vitagraph, directing most of the films made by Florence Turner and John Bunny, as well as those made by Jean. In December 1912, Jean gave birth to six puppies — two male and four female — and was the subject of the Vitagraph documentary short, Jean and Her Family (Larry Trimble, 1913). In March 1913, Trimble and Jean left Vitagraph and accompanied Florence Turner to England, where she formed her own company, Turner Films. Trimble and his canine star returned to the United States in 1916. Jean died later that year, at age 14.

Helen Case. French postcard, probably by the French subsidiary of The Vitagraph Co., Paris, no. 13.

E.R. Phillips. French postcard, probably by the French subsidiary of The Vitagraph Co., Paris, no. 14.

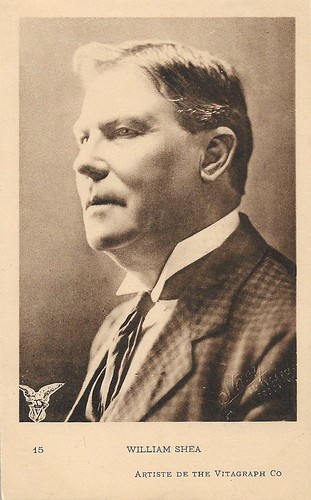

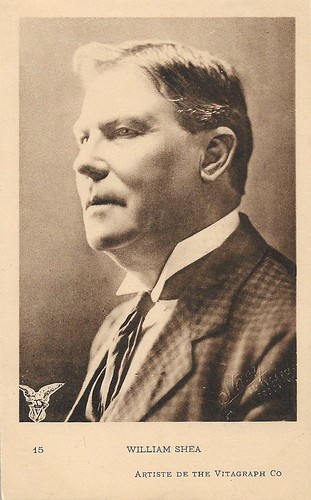

Wiliam Shea. French postcard, probably by the French subsidiary of The Vitagraph Co., Paris, no. 15.

Norma Talmadge. French postcard, probably by the French subsidiary of The Vitagraph Co., Paris, no. 16. In contrast to most American film companies, who had London as their hub for the European film distribution market, Vitagraph arranged its European publicity from Paris, including the astonishing film posters (de)signed by Harry Bedos. Between 1909 and 1915 Norma Talmadge was one of the regular actors at Vitagraph, acting in hundreds of shorts, but also in the feature The Battle Cry of Peace (J. Stuart Blackton, Wilfrid North, 1915).

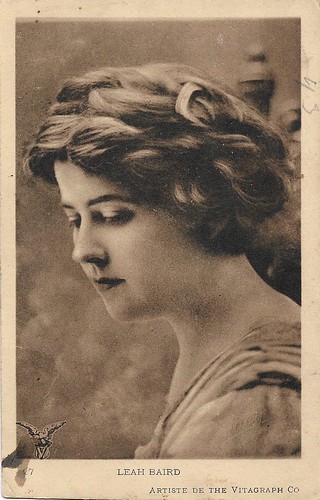

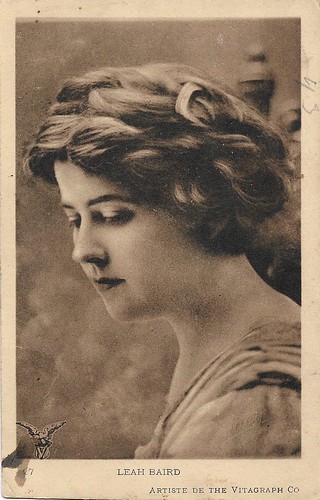

Leah Baird. French postcard, probably by the French subsidiary of The Vitagraph Co., Paris, no. 27.

Multiple-reel films had appeared in the United States as early as 1907, when Adolph Zukor distributed Pathé’s three-reel Vie et Passion de N.S. Jésus Christ/Passion Play (Ferdinand Zecca, 1907). In 1909, Vitagraph distributed the first film adaptation of Victor Hugo’s novel Les Misérables as a proto-feature film: four short films that can be seen separately, but when combined appear as a short film series resembling that of a full-length feature film. In Les Misérables (J. Stuart Blackton, 1909), Maurice Costello stars as Jean Valjean, an honest man who is running from the obsessive police inspector Javert (William V. Ranous) chasing him for an insignificant offence. The film consists of four reels, each released over the course of three months from 4 September till 27 November 1909.

In 1910, cinemas showed the five parts of the Vitagraph serial The Life of Moses (J. Stuart Blackton,1909) consecutively. It was the first of a series of Biblical pictures. With a total length of almost 90 minutes, The Life of Moses claims the title of ‘the first feature film.’ The MPPC had forced Vitagraph to release it in serial fashion at the rate of one reel a week. Two years later, the multiple-reel film — which came to be called a 'feature', in the vaudevillian sense of a headline attraction — achieved general acceptance with the smashing success of the three-and-one-half-reel French film La Reine Elisabeth/Queen Elizabeth (Louis Mercanton, 1912), which starred Sarah Bernhardt and was imported by Adolph Zukor. Then the nine-reel Italian ‘super spectacle’ Quo Vadis? (Enrico Guazzoni, 1912) was road-shown in legitimate theatres across the country at a top admission price of one dollar, and the feature craze was on. Vitagraph had missed the boat.

From 1910 on, comedian John Bunny started to make short films for Vitagraph. Bunny was 48 years old at the time, and had enjoyed a very successful career on stage. In the following years, he made over 150 short films, many of them marital situation comedies. In these comedies such as A Cure for Pokeritis (Larry Trimble, 1912) and Bunny as a Reporter (Wilfrid North, 1913), the rotund Bunny was coupled with the thin and small comedian Flora Finch. John Bunny became the most popular film comedian in the world in the years before Charlie Chaplin. In 1915, Bunny had been acting in films for only five years when he died from Bright's disease at his home in Brooklyn. His death was observed worldwide.

Vitagraph also produced the first aviation film, The Military Air-Scout (William J. Humphrey, 1911). The U.S. Army authorities had allowed Lieutenant - and future General of the Air Force - Henry ‘Hap’ Arnold to carry out the stunt flying for the film. He doubled for the lead actor Earle Williams. Arnold had brought his Army Wright Model F/Wright Burgess Hydro biplane from College Park Airport, Maryland, by train. Flight operations were conducted from the Nassau Boulevard aerodrome in Garden City, Long Island, and were completed in October 1911. Arnold, who picked up 'a few extra bucks' for his services, became so excited about films that he almost quit the Army to become an actor.

Vitagraph made two ‘super productions’ in late 1913, early 1914, A Million Dollar Bid at five reels and The Christian at eight reels, but exhibitors were not convinced that the public would come. Smith and Blackton decided to test the big pictures and did something no other producing company had done at that point - they became exhibitors. They leased the Criterion Theatre on Broadway in New York, renamed it the Vitagraph Theatre, and opened it in February 1914, with a sketch, a short and A Million Dollar Bid (Ralph Ince, 1914) which starred Anita Stewart and Julia Swayne Gordon. The opening was a success. In May, they leased the Harris Theatre on 42nd Street and opened with The Christian (Frederick A. Thomson, 1914) which starred Earle Williams and Edith Storey. This, too, was a success. Exhibitors became very concerned about this new venture and confronted Vitagraph about their concerns. After a meeting with a committee of exhibitors, Vitagraph announced it would acquire no more theatres, although this was to become a common practice of film producers in the ensuing years.

Upon its release, The Battle Cry of Peace (J. Stuart Blackton, Wilfrid North, 1915) generated a controversy rivalling that of Birth of a Nation because it was considered to be militaristic propaganda. Producer Stuart Blackton believed that the US should join the Allies involved in World War I overseas, and that was why he made the film. Former President Theodore Roosevelt was one of the film's staunchest supporters, and he persuaded Gen. Leonard Wood to lend Blackton an entire regiment of Marines to use as extras. Ironically, after America declared war, the film was modified for re-release because it was seen as not being sufficiently pro-war.

World War I spelled the beginning of the end for Vitagraph. With the loss of foreign distributors and the rise of the monopolistic Studio system, Vitagraph was slowly but surely being squeezed out of the business. The General Film company of the MPPC continued to distribute their shorts domestically, but it became necessary to form a new releasing organisation. In 1915, Chicago distributor George Kleine orchestrated a four-way film distribution partnership, V-L-S-E, Incorporated, for the Vitagraph, Lubin, Selig, and Essanay companies. Albert Smith served as president. In 1916, Benjamin Hampton proposed a merger of the distribution companies Paramount Pictures and V-L-S-E with Famous Players and Jesse L. Lasky Feature Play Company, but was foiled by Adolph Zukor. V-L-S-E was dissolved in August, 1916, when Vitagraph purchased a controlling interest in Lubin, Selig, and Essanay.

New names began to be added to Vitagraph's roster during these years that would be some of the most famous names of the silent era. Norma Talmadge came to Vitagraph straight from Erasmus High School in Flatbush in 1910. Wallace Reid joined in 1911 after a short stint with Selig. One of the most famous cowboys stars of the 1920s, Fred Thomson, started his career with Vitagraph. Jane Novak came to the studio in 1913 because her aunt, Anne Schaefer, was already a star with Vitagraph. Clara Kimball Young made her first Vitagraph film in 1912. Both Bebe Daniels and Mabel Normand spent a short time with the company. Antonio Moreno entered films with the Vitagraph Company in 1914. Alice Joyce's name was added to the roster in 1916 when Vitagraph purchased the Kalem studio where she was already a popular star. Comedian Larry Semon joined the company in 1917.

‘Pop’ Rock died in 1916 leaving Albert E. Smith and J. Stuart Blackton to run the company without their elder mentor. Blackton resigned in 1917. He went into independent production for a while, but it proved to be an unsuccessful venture. He also unsuccessfully took a turn at producing films in England, but he returned to Vitagraph as 1923 as an equal partner once again with Smith. In 1919, the General Film Company folded. In the early 1920s, the company was feeling the effects of the bigger film companies who were emerging, buying up theatres across the country and releasing more and bigger pictures than Vitagraph. In September, 1922, the company estimated its losses to be nearly a million dollars.

Though most of the company's features in the 1920s were programmers, two top quality productions enjoyed both critical and financial success. Black Beauty (David Smith, 1921) and Captain Blood (David Smith, Albert E. Smith, 1924) both starred Smith's wife, Jean Paige. In April 1925, Blackton and Smith finally gave up and sold the company to Warner Bros. for a comfortable profit. The Flatbush studio (renamed Vitaphone) was later used as an independent unit within Warner Bros., specialising in early sound shorts.

After losing his fortune in the economic depression of 1929, J. Stuart Blackton supported himself by exhibiting his old films at sideshows. He died in 1941. In 1952, Albert E. Smith, in collaboration with co-author Phil A. Koury, wrote an autobiography, ‘Two Reels and a Crank’. It includes a very detailed history of Vitagraph and a lengthy list of people who had been in the Vitagraph Family which also included Billy Anderson, Richard Barthelmess, Francis X. Bushman, Dustin Farnum, Hoot Gibson, Corinne Griffith, Alan Hale, Oliver Hardy, Mildred Harris, Hedda Hopper, Rex Ingram, Boris Karloff, J. Warren Kerrigan, Rod La Rocque, Viola Dana, Bessie Love, May McAvoy, Victor McLaglen, Adolphe Menjou, Conrad Nagel, May Robson, Wesley Ruggles, George Stevens, William Desmond Taylor, Alice Terry, Moe Howard of The Three Stooges, and hundreds of other people are listed. In his book, Smith also refers to hiring a 17-year-old Rudolph Valentino into the set-decorating department, but within a week he was being used by directors as an extra in foreign parts, mainly as a Russian Cossack.

In 1910, a fire had destroyed virtually all of the negatives of every film the Vitagraph company had made since 1896. Today, many of the early Vitagraph films are considered lost. During the 1980s, nearly 80 distribution prints were discovered in the Desmet collection of the EYE Filmmuseum in Amsterdam. They created a sensation when shown on international filmfestivals.

Eileen Bowser, former Film Curator of the Museum of Modern Art in New York: "We certainly began to have a new idea of the importance of the Vitagraph production after the Desmet collection began to come accessible. Only a small number of Vitagraphs were available in the U.S. prior to that." Peter Delpeut, former curator at EYE Filmmuseum: "What astonished me most was the formal power of the Vitagraph films. They showed a phenomenal consistency of style, as if all produced by a single filmmaker with a predilection for rock-solid frames within which carefully positioned actors acted out the stories in clear dramatic statements."

From 1960 to 1969, the Vitagraph name was briefly resurrected at the end of Warner Bros.' Looney Tunes cartoons with the end titles reading "A Warner Bros. Cartoon / A Vitagraph Release". That’s all Folks!

Alice Joyce. French postcard in the Les Vedettes du Cinéma series by Editions Filma, no. 35. Photo: Vitagraph.

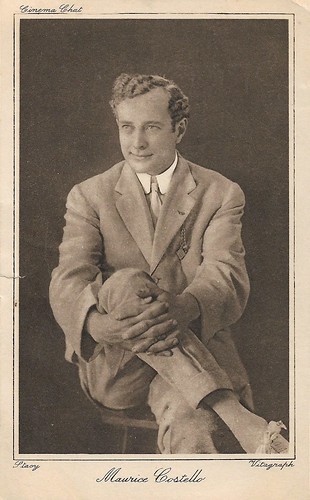

Maurice Costello. British Postcard in the Cinema Chat series. Photo: Stacy.

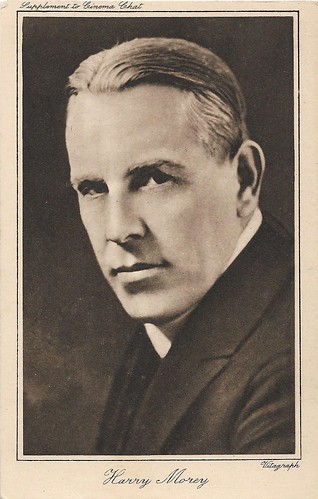

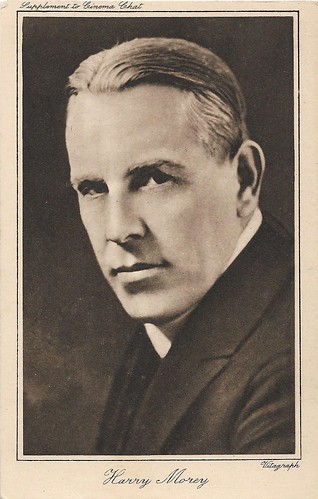

Harry Morey. British Postcard in the Cinema Chat series. Photo: Vitagraph.

Antonio Moreno. British Postcard in the Cinema Chat series. Photo: Vitagraph.

Jean Paige. British Postcard in the Cinema Chat series. Photo: Hill / Vitagraph.

Sources: Ivo Blom (Pionierswerk. Jean Desmet en de vroege Nederlandse filmhandel en bioscoopexploitatie (1907-1916) - Dutch), Mark-Paul Meijer (Jean Desmet's Dream Factory), Tim Lussier (Silents are Golden), Encyclopaedia Brittanica, Silent Era, Wikipedia and IMDb.

American postcard by The Ess an Ess Photo Co., New York. Photo: Vitagraph. Caption: Florence E. Turner, Vitagraph Players.

British postcard. Editor unknown. Caption: Maurice Costello, of the Vitagraph Players.

John Bunny. British or American postcard. Editor unknown.

British postcard. Editor unknown. Caption: Flora Finch, of the Vitagraph Players.

British postcard. Editor unknown. Caption: Lilian Walker, of the Vitagraph Players.

The first modern film studio in the U.S.

In 1896, English émigré J. Stuart Blackton worked for the New York Evening World when he was sent to interview Thomas Edison about his new film projector. The inventor talked the entrepreneurial reporter into buying a set of films and a projector. A year later, Blackton and business partner Albert E. Smith founded the American Vitagraph Company in direct competition with Edison. Vitagraph made its debut at Tony Pastor's New Fourteenth Street Theatre on 23 March 1896, with fellow Brit Ronald Reader as projectionist. Blackton and Smith performed vaudeville acts, but with the addition of motion pictures that were typical of the day - a train coming into the station, the Niagara Falls, a man shovelling snow, a boy romping with his dog and anything else that showed movement. A third partner, distributor William ‘Pop’ Rock, joined in 1899.

The company's first studio was located on the rooftop of 140 Nassau Street in Lower Manhattan. There Blackton and Smith shot their first film, The Burglar on the Roof (1897). Tim Lussier at Silents are Golden: “The film was supposed to only involve a burglar (played by Blackton) and a policeman, however, when the ‘policeman’ began struggling with the ‘burglar,’ Mrs. Olsen, the wife of the building's janitor, came on the scene. Thinking she had happened upon the real thing, she began beating the ‘burglar’ with her broom. At first worried that their film was ruined, they were pleased to see the favorable reaction from the audience at Pastor's the next evening.” Operations were later moved to the spacious and less expensive Midwood neighbourhood of Brooklyn, New York. Vitagraph produced The Humpty Dumpty Circus (J. Stuart Blackton, 1897 or 1898), which was the first film to use the stop-motion technique. The film featured a circus with acrobats and animals in motion.

The reputation of the American Vitagraph Company was bolstered greatly by the filming of some major historical events around the turn of the century like the Spanish-American War of 1898, the Boer War in South Africa in 1900, the 1904 inauguration of President Theodore Roosevelt and the aftermath of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. When the dead from the Maine explosion were brought back to Arlington Cemetery in Washington, D.C., Vitagraph was there to film it with very successful, and emotional, results. Smith and Blackton then managed to gain passage to Cuba on the same ship that Teddy Roosevelt and his Rough Riders were on eventually accompanying him on his famous 'charge' up San Juan Hill. These shorts were among the first works of film propaganda, and a few had that most characteristic fault of propaganda, studio re-enactments being passed off as footage of actual events. The Battle of Santiago Bay (J. Stuart Blackton, 1898) was filmed in an improvised bathtub, with the ‘smoke of battle’ provided by Mrs. Blackton's cigar. It still proved believable to the filmgoers of the day and was very, very popular. The American Vitagraph Company made many contributions to the history of film-making. In 1903 the Austrian director Joseph Delmont started his career by producing Westerns, one-reel pictures lasting only a few minutes. He later became famous by using ‘wild carnivores’ in his films — a sensation for that time. In 1906, Vitagraph opened a glass-enclosed studio in New York, the first modern film studio in the U.S. Very successful proved the foreign operations of the studio and Vitagraph opened offices in London, Paris and Berlin in 1908. In 1911, they created a second film studio in Santa Monica, California, and a year later moved to a 29-acre sheep ranch in the Los Feliz district of Los Angeles, a studio subsequently owned by ABC and currently Disney Studios.

The American Vitagraph company temporarily ceased production in January 1901 due to Edison patents lawsuits. Vitagraph was not the only company seeking to make money from Edison's motion picture inventions, and Edison's lawyers were very busy in the 1890s and 1900s filing patents and suing competitors for patent infringement. The company resumed production after a distribution agreement was reached with Edison Manufacturing Company in 1902. By circa 1904, the company was again handling its own distribution. Blackton did his best to avoid lawsuits by buying a special license from Edison in 1907 and by agreeing to sell many of his most popular films to Edison for distribution. In 1909, Vitagraph was one of the original ten production companies included in Edison's attempt to corner film-making, the Motion Picture Patents Company (MPPC), a trust of all the major USA film companies and local foreign-branches (Edison, Biograph, Vitagraph, Essanay, Selig Polyscope, Lubin Manufacturing, Kalem Company, Star Film Paris, American Pathé), the leading film distributor (George Kleine) and the biggest supplier of raw film stock, Eastman Kodak. From 1911 through circa April 1915, all the product of the MPPC members was distributed by The General Film Company. MPPC ended the domination of foreign films on American screens, standardised the manner in which films were distributed and exhibited within the USA, and improved the quality of American films by internal competition. But it also discouraged its members' entry into feature film production, and the use of outside financing, both to its members' eventual detriment. Vitagraph did not release its first features until 1914, after dozens, if not hundreds, of feature films had been released by independents.

By 1909, the Vitagraph Company began to release three reels of film a week and had 30 actors and actresses and seven directors under contract, in addition to technical and business staff. Vitagraph created one of the world's first film stars, Florence Turner also known as 'the Vitagraph Girl'. She had made her film debut in How to Cure a Cold (1907). At the time there were no stars per se, unless an already famous stage star made a film. Performers were not even mentioned by name. The Vitagraph Girl became the most popular American actress to appear on screen which was at that time still dominated by French pictures, especially from the Pathé and Gaumont companies. Her worth to the studio, as its biggest box-office draw, was recognised in 1907 when her pay was upped to $22 a week, as proto-star plus part-time seamstress. Florence was paired several times with heart throb Wallace Reid, who was also on his way to stardom. In March 1910, Turner and Florence Lawrence became the first screen actors not already famous in another medium to be publicised by name by their studios to the general public. But with the rise of more stars, such as Mary Pickford at Biograph Studios, Florence Turner was no longer quite as special. By 1913 she was looking for new pastures and left the United States accompanied by director Laurence Trimble. They moved to England, where she and Trimble began performing together in London music halls and started their own film company.

The first of the matinee idols was the super-popular Maurice Costello, who had been a prominent vaudeville actor of the late 1890s and early 1900s. In 1908, Costello joined Vitagraph, and thus also became a member of the first motion picture stock company ever formed. Among some of his best known pictures are the condensed Charles Dickens adaptation A Tale of Two Cities (William Humphrey, 1911), The Man Who Couldn't Beat God (Maurice Costello, Robert Gaillard, 1915) and For the Honor of the Family (Van Dyke Brooke, 1912) with his young daughter Dolores Costello as a child. Later, he found the transition to ‘talkies’ extremely difficult, and his leading man status was over. However, Costello was a trouper, and continued to appear in films, often in small roles and bit parts, right up until his death in 1950.

Vitagraph produced a series of William Shakespeare adaptations, the first American adaptations of the Bard's works. The series included Macbeth (James Stuart Blackton, 1908) starring William Ranous, Romeo and Juliet (James Stuart Blackton, 1908) with Paul Panzer as Romeo and Florence Lawrence as Juliet, and A Midsummer Night's Dream (Charles Kent, J. Stuart Blackton, 1909) with Maurice Costello as Lysander. Most of these short films are considered lost now. Vitagraph also was the first to film one of Mark Twain's stories, A Curious Dream (J. Stuart Blackton, 1904 or 1907), with the author's blessings. And several other Vitagraph films were centred on such well-known characters as Sherlock Holmes, Oliver Twist, Salome, Richelieu, Moses, and Saul and David.

The first animal star of the Silent Era was Jean, the Vitagraph Dog. Jean was a female Scotch Collie, owned and guided by director Laurence Trimble. From 1910 on, Jean was starring in her own short films, all directed by Trimble. One-reelers and two-reelers with titles such as Jean and the Calico Doll (Larry Trimble, 1910), Jean and the Waif (Larry Trimble, 1910) and Jean Goes Fishing (Larry Trimble, 1910) were made by Trimble as the Vitagraph troupe filmed along the coastline in his native Maine. Actress Helen Hayes played as an eight-year-old with long curls the juvenile lead in Jean and the Calico Doll (Larry Trimble, 1910). Trimble became a leading director at Vitagraph, directing most of the films made by Florence Turner and John Bunny, as well as those made by Jean. In December 1912, Jean gave birth to six puppies — two male and four female — and was the subject of the Vitagraph documentary short, Jean and Her Family (Larry Trimble, 1913). In March 1913, Trimble and Jean left Vitagraph and accompanied Florence Turner to England, where she formed her own company, Turner Films. Trimble and his canine star returned to the United States in 1916. Jean died later that year, at age 14.

Helen Case. French postcard, probably by the French subsidiary of The Vitagraph Co., Paris, no. 13.

E.R. Phillips. French postcard, probably by the French subsidiary of The Vitagraph Co., Paris, no. 14.

Wiliam Shea. French postcard, probably by the French subsidiary of The Vitagraph Co., Paris, no. 15.

Norma Talmadge. French postcard, probably by the French subsidiary of The Vitagraph Co., Paris, no. 16. In contrast to most American film companies, who had London as their hub for the European film distribution market, Vitagraph arranged its European publicity from Paris, including the astonishing film posters (de)signed by Harry Bedos. Between 1909 and 1915 Norma Talmadge was one of the regular actors at Vitagraph, acting in hundreds of shorts, but also in the feature The Battle Cry of Peace (J. Stuart Blackton, Wilfrid North, 1915).

Leah Baird. French postcard, probably by the French subsidiary of The Vitagraph Co., Paris, no. 27.

The most popular film comedian in the world

Multiple-reel films had appeared in the United States as early as 1907, when Adolph Zukor distributed Pathé’s three-reel Vie et Passion de N.S. Jésus Christ/Passion Play (Ferdinand Zecca, 1907). In 1909, Vitagraph distributed the first film adaptation of Victor Hugo’s novel Les Misérables as a proto-feature film: four short films that can be seen separately, but when combined appear as a short film series resembling that of a full-length feature film. In Les Misérables (J. Stuart Blackton, 1909), Maurice Costello stars as Jean Valjean, an honest man who is running from the obsessive police inspector Javert (William V. Ranous) chasing him for an insignificant offence. The film consists of four reels, each released over the course of three months from 4 September till 27 November 1909.

In 1910, cinemas showed the five parts of the Vitagraph serial The Life of Moses (J. Stuart Blackton,1909) consecutively. It was the first of a series of Biblical pictures. With a total length of almost 90 minutes, The Life of Moses claims the title of ‘the first feature film.’ The MPPC had forced Vitagraph to release it in serial fashion at the rate of one reel a week. Two years later, the multiple-reel film — which came to be called a 'feature', in the vaudevillian sense of a headline attraction — achieved general acceptance with the smashing success of the three-and-one-half-reel French film La Reine Elisabeth/Queen Elizabeth (Louis Mercanton, 1912), which starred Sarah Bernhardt and was imported by Adolph Zukor. Then the nine-reel Italian ‘super spectacle’ Quo Vadis? (Enrico Guazzoni, 1912) was road-shown in legitimate theatres across the country at a top admission price of one dollar, and the feature craze was on. Vitagraph had missed the boat.

From 1910 on, comedian John Bunny started to make short films for Vitagraph. Bunny was 48 years old at the time, and had enjoyed a very successful career on stage. In the following years, he made over 150 short films, many of them marital situation comedies. In these comedies such as A Cure for Pokeritis (Larry Trimble, 1912) and Bunny as a Reporter (Wilfrid North, 1913), the rotund Bunny was coupled with the thin and small comedian Flora Finch. John Bunny became the most popular film comedian in the world in the years before Charlie Chaplin. In 1915, Bunny had been acting in films for only five years when he died from Bright's disease at his home in Brooklyn. His death was observed worldwide.

Vitagraph also produced the first aviation film, The Military Air-Scout (William J. Humphrey, 1911). The U.S. Army authorities had allowed Lieutenant - and future General of the Air Force - Henry ‘Hap’ Arnold to carry out the stunt flying for the film. He doubled for the lead actor Earle Williams. Arnold had brought his Army Wright Model F/Wright Burgess Hydro biplane from College Park Airport, Maryland, by train. Flight operations were conducted from the Nassau Boulevard aerodrome in Garden City, Long Island, and were completed in October 1911. Arnold, who picked up 'a few extra bucks' for his services, became so excited about films that he almost quit the Army to become an actor.

Vitagraph made two ‘super productions’ in late 1913, early 1914, A Million Dollar Bid at five reels and The Christian at eight reels, but exhibitors were not convinced that the public would come. Smith and Blackton decided to test the big pictures and did something no other producing company had done at that point - they became exhibitors. They leased the Criterion Theatre on Broadway in New York, renamed it the Vitagraph Theatre, and opened it in February 1914, with a sketch, a short and A Million Dollar Bid (Ralph Ince, 1914) which starred Anita Stewart and Julia Swayne Gordon. The opening was a success. In May, they leased the Harris Theatre on 42nd Street and opened with The Christian (Frederick A. Thomson, 1914) which starred Earle Williams and Edith Storey. This, too, was a success. Exhibitors became very concerned about this new venture and confronted Vitagraph about their concerns. After a meeting with a committee of exhibitors, Vitagraph announced it would acquire no more theatres, although this was to become a common practice of film producers in the ensuing years.

Upon its release, The Battle Cry of Peace (J. Stuart Blackton, Wilfrid North, 1915) generated a controversy rivalling that of Birth of a Nation because it was considered to be militaristic propaganda. Producer Stuart Blackton believed that the US should join the Allies involved in World War I overseas, and that was why he made the film. Former President Theodore Roosevelt was one of the film's staunchest supporters, and he persuaded Gen. Leonard Wood to lend Blackton an entire regiment of Marines to use as extras. Ironically, after America declared war, the film was modified for re-release because it was seen as not being sufficiently pro-war.

World War I spelled the beginning of the end for Vitagraph. With the loss of foreign distributors and the rise of the monopolistic Studio system, Vitagraph was slowly but surely being squeezed out of the business. The General Film company of the MPPC continued to distribute their shorts domestically, but it became necessary to form a new releasing organisation. In 1915, Chicago distributor George Kleine orchestrated a four-way film distribution partnership, V-L-S-E, Incorporated, for the Vitagraph, Lubin, Selig, and Essanay companies. Albert Smith served as president. In 1916, Benjamin Hampton proposed a merger of the distribution companies Paramount Pictures and V-L-S-E with Famous Players and Jesse L. Lasky Feature Play Company, but was foiled by Adolph Zukor. V-L-S-E was dissolved in August, 1916, when Vitagraph purchased a controlling interest in Lubin, Selig, and Essanay.

New names began to be added to Vitagraph's roster during these years that would be some of the most famous names of the silent era. Norma Talmadge came to Vitagraph straight from Erasmus High School in Flatbush in 1910. Wallace Reid joined in 1911 after a short stint with Selig. One of the most famous cowboys stars of the 1920s, Fred Thomson, started his career with Vitagraph. Jane Novak came to the studio in 1913 because her aunt, Anne Schaefer, was already a star with Vitagraph. Clara Kimball Young made her first Vitagraph film in 1912. Both Bebe Daniels and Mabel Normand spent a short time with the company. Antonio Moreno entered films with the Vitagraph Company in 1914. Alice Joyce's name was added to the roster in 1916 when Vitagraph purchased the Kalem studio where she was already a popular star. Comedian Larry Semon joined the company in 1917.

‘Pop’ Rock died in 1916 leaving Albert E. Smith and J. Stuart Blackton to run the company without their elder mentor. Blackton resigned in 1917. He went into independent production for a while, but it proved to be an unsuccessful venture. He also unsuccessfully took a turn at producing films in England, but he returned to Vitagraph as 1923 as an equal partner once again with Smith. In 1919, the General Film Company folded. In the early 1920s, the company was feeling the effects of the bigger film companies who were emerging, buying up theatres across the country and releasing more and bigger pictures than Vitagraph. In September, 1922, the company estimated its losses to be nearly a million dollars.

Though most of the company's features in the 1920s were programmers, two top quality productions enjoyed both critical and financial success. Black Beauty (David Smith, 1921) and Captain Blood (David Smith, Albert E. Smith, 1924) both starred Smith's wife, Jean Paige. In April 1925, Blackton and Smith finally gave up and sold the company to Warner Bros. for a comfortable profit. The Flatbush studio (renamed Vitaphone) was later used as an independent unit within Warner Bros., specialising in early sound shorts.

After losing his fortune in the economic depression of 1929, J. Stuart Blackton supported himself by exhibiting his old films at sideshows. He died in 1941. In 1952, Albert E. Smith, in collaboration with co-author Phil A. Koury, wrote an autobiography, ‘Two Reels and a Crank’. It includes a very detailed history of Vitagraph and a lengthy list of people who had been in the Vitagraph Family which also included Billy Anderson, Richard Barthelmess, Francis X. Bushman, Dustin Farnum, Hoot Gibson, Corinne Griffith, Alan Hale, Oliver Hardy, Mildred Harris, Hedda Hopper, Rex Ingram, Boris Karloff, J. Warren Kerrigan, Rod La Rocque, Viola Dana, Bessie Love, May McAvoy, Victor McLaglen, Adolphe Menjou, Conrad Nagel, May Robson, Wesley Ruggles, George Stevens, William Desmond Taylor, Alice Terry, Moe Howard of The Three Stooges, and hundreds of other people are listed. In his book, Smith also refers to hiring a 17-year-old Rudolph Valentino into the set-decorating department, but within a week he was being used by directors as an extra in foreign parts, mainly as a Russian Cossack.

In 1910, a fire had destroyed virtually all of the negatives of every film the Vitagraph company had made since 1896. Today, many of the early Vitagraph films are considered lost. During the 1980s, nearly 80 distribution prints were discovered in the Desmet collection of the EYE Filmmuseum in Amsterdam. They created a sensation when shown on international filmfestivals.

Eileen Bowser, former Film Curator of the Museum of Modern Art in New York: "We certainly began to have a new idea of the importance of the Vitagraph production after the Desmet collection began to come accessible. Only a small number of Vitagraphs were available in the U.S. prior to that." Peter Delpeut, former curator at EYE Filmmuseum: "What astonished me most was the formal power of the Vitagraph films. They showed a phenomenal consistency of style, as if all produced by a single filmmaker with a predilection for rock-solid frames within which carefully positioned actors acted out the stories in clear dramatic statements."

From 1960 to 1969, the Vitagraph name was briefly resurrected at the end of Warner Bros.' Looney Tunes cartoons with the end titles reading "A Warner Bros. Cartoon / A Vitagraph Release". That’s all Folks!

Alice Joyce. French postcard in the Les Vedettes du Cinéma series by Editions Filma, no. 35. Photo: Vitagraph.

Maurice Costello. British Postcard in the Cinema Chat series. Photo: Stacy.

Harry Morey. British Postcard in the Cinema Chat series. Photo: Vitagraph.

Antonio Moreno. British Postcard in the Cinema Chat series. Photo: Vitagraph.

Jean Paige. British Postcard in the Cinema Chat series. Photo: Hill / Vitagraph.

Sources: Ivo Blom (Pionierswerk. Jean Desmet en de vroege Nederlandse filmhandel en bioscoopexploitatie (1907-1916) - Dutch), Mark-Paul Meijer (Jean Desmet's Dream Factory), Tim Lussier (Silents are Golden), Encyclopaedia Brittanica, Silent Era, Wikipedia and IMDb.

No comments:

Post a Comment