Columbia Pictures or Columbia is one of the 'Big Six' major American film studios, and was one of the 'Little Three' among the eight major film studios of Hollywood's Golden Age. Studio Mogul was the notoriously hard-driving and vulgar Harry Cohn. Initially Columbia had the worst reputation and smallest budgets, but in the late 1920s the studio began to grow, spurred by a successful association with director Frank Capra. In the 1930s, Columbia became one of the primary homes of the screwball comedy, and contract stars were Jean Arthur and Cary Grant. In the 1940s, Rita Hayworth became Columbia's premier star and Rosalind Russell, Glenn Ford, and William Holden also became major stars at the studio. Today, it has become the world's fifth largest major film studio and is a member of the Sony Pictures Motion Picture Group.

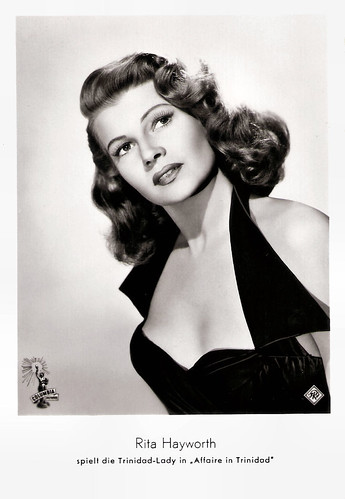

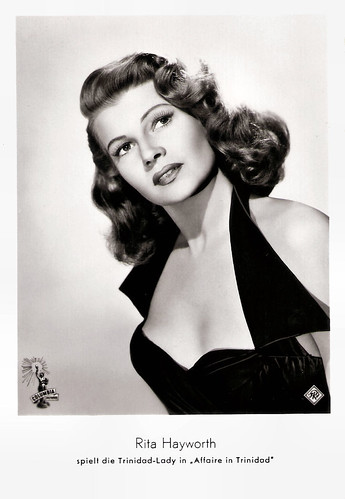

Rita Hayworth. Belgian postcard by Victoria, Brussels, no. 639. Photo: Columbia Pictures.

Cary Grant. British postcard in the Picturegoer Series, London, no. 735c. Photo: Columbia.

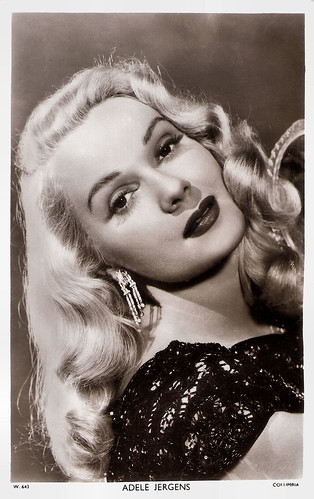

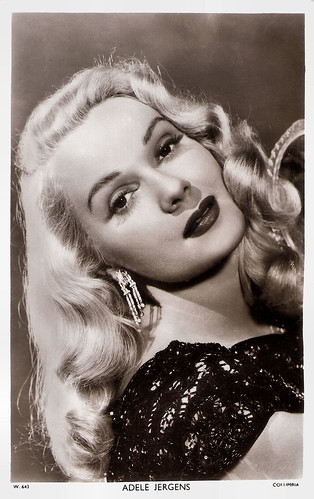

Adele Jergens. British postcard in Picturegoer Series, London, no. W 643. Photo: Columbia.

Claudette Colbert. Dutch postcard by J.S.A.. Photo: Columbia. Publicity still for Tomorrow is Forever (Irving Pichel, 1946).

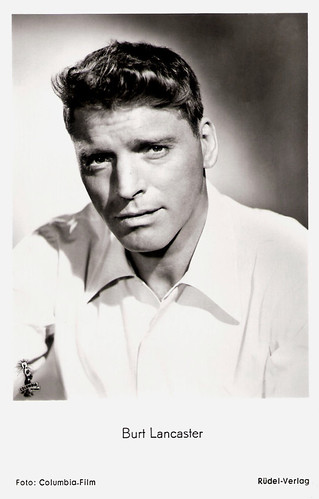

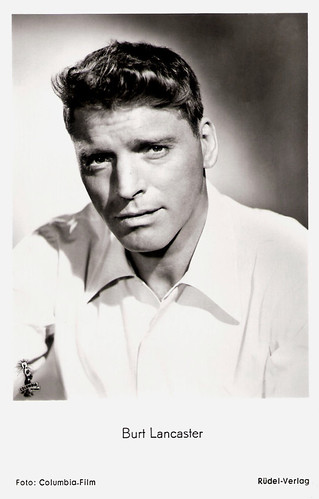

Burt Lancaster. German postcard by Franz Josef Rüdel, Filmpostkartenverlag, Hamburg-Bergedorf, no. 858. Photo: Columbia-Film. Publicity still for From Here to Eternity (Fred Zinnemann, 1953).

Columbia was founded in June 1918 as Cohn-Brandt-Cohn (CBC) Film Sales by brothers Jack and Harry Cohn and Jack's best friend Joe Brandt. Jack had worked for Carl Laemmle at Universal, Joe had been Laemmle’s executive secretary and Jack’s younger brother Harry, had also worked at Universal.They released their first feature film in August 1922. Brandt was president of CBC Film Sales, handling sales, marketing and distribution from New York along with Jack Cohn, while Harry Cohn ran production in Hollywood.

The studio's early productions were low-budget short subjects: 'Screen Snapshots', the 'Hall Room Boys' (the vaudeville duo of Edward Flanagan and Neely Edwards), and the Chaplin imitator Billy West. The start-up CBC leased space in a Poverty Row studio on Hollywood's famously low-rent Gower Street. Among Hollywood's elite, the studio's small-time reputation led some to joke that CBC stood for 'Corned Beef and Cabbage'. Brandt eventually tired of dealing with the Cohn brothers, and he sold his one-third stake to Harry Cohn, who took over as president.

In an effort to improve its image, the Cohn brothers renamed the company Columbia Pictures Corporation in 1924. Cohn remained head of production as well, thus concentrating enormous power in his hands. He would run Columbia for the next 34 years, the second-longest tenure of any studio chief, behind only Warner Bros.' Jack L. Warner. Even in an industry rife with nepotism, Columbia was particularly notorious for having a number of Harry and Jack's relatives in high positions. Humorist Robert Benchley called it the Pine Tree Studio, "because it has so many Cohns".

Columbia's product line consisted mostly of moderately budgeted features and short subjects including comedies, sports films, various serials, and cartoons. Columbia gradually moved into the production of higher-budget fare, eventually joining the second tier of Hollywood studios along with United Artists and Universal. Like United Artists and Universal, Columbia was a horizontally integrated company. It controlled production and distribution; it did not own any theatres.

Helping Columbia's climb was the arrival of an ambitious director, Frank Capra. Between 1927 and 1939, Capra constantly pushed Cohn for better material and bigger budgets. A string of hits he directed in the early and mid 1930s solidified Columbia's status as a major studio. In particular, It Happened One Night (Frank Capra, 1934) with Clark Gable and Claudette Colbert put Columbia on the map. It won the Academy Award for Best Film of 1934.

Until then, Columbia's very existence had depended on theatre owners willing to take its films, since as mentioned above it didn't have a theatre network of its own. Other Capra-directed hits followed, including Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (Frank Capra, 1936), the original version of Lost Horizon (Frank Capra, 1937) with Ronald Colman, You Can’t Take it With You (Frank Capra, 1938), which was Capra's highest-grossing picture at Columbia, and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (Frank Capra, 1939), which made James Stewart a major star.

Capra but also Howard Hawks and others made some of the finest screwball comedies of the 1930s for Columbia: The Awful Truth (Leo McCarey, 1937), Holiday (George Cukor, 1938), and His Girl Friday (Howard Hawks, 1940), all starring Cary Grant. After Capra’s departure in 1939, Columbia languished because leading directors were reluctant to work for the notoriously hard-driving and vulgar Cohn.

In 1938, the addition of B. B. Kahane as Vice President would produce Charles Vidor's Those High Gray Walls (Charles Vidor, 1939), and The Lady in Question (Charles Vidor, 1940), the first joint film of Rita Hayworth and Glenn Ford. Kahane would later become the President of Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in 1959, until his death a year later.

Tullio Carminati and Grace Moore. British postcard in the Film Partners Series, London, no. P 151. Photo: Columbia. Publicity still for One Night of Love (Victor Schertzinger, 1934).

Claudette Colbert. Italian postcard by Rizzoli, Milano, 1937. Photo: Columbia.

Ronald Colman and Jane Wyatt. Italian postcard by Vecchioni & Guadagno, Roma. Photo: Columbia EIA. Publicity still for Lost Horizon (Frank Capra, 1937).

Marie McDonald. Dutch postcard by J.S.A. Photo: Columbia.

Sonja Henie. Dutch Postcard by J.S.A. Photo: Columbia F.B. / M.P.E.

Columbia could not afford to keep a huge roster of contract stars, so Cohn usually borrowed them from other studios. At Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, the industry's most prestigious studio, Columbia was nicknamed 'Siberia, as Louis B. Mayer would use the loan out to Columbia as a way to punish his less-obedient signings. In the 1930s, Columbia signed Jean Arthur to a long-term contract, and after The Whole Town's Talking (John Ford, 1935), Arthur became a major comedy star. Ann Sothern's career was launched when Columbia signed her to a contract in 1936. Cary Grant signed a contract in 1937 and soon after it was altered to a non-exclusive contract shared with RKO.

Many theatres relied on Westerns to attract big weekend audiences, and Columbia always recognised this market. Its first cowboy star was Buck Jones, who signed with Columbia in 1930 for a fraction of his former big-studio salary. Over the next two decades Columbia released scores of outdoor adventures with Jones, Tim McCoy, Ken Maynard, Robert (Tex) Allen, and Gene Autry. Columbia's most popular cowboy was Charles Starrett, who signed with Columbia in 1935 and starred in 131 western features over 17 years.

At Harry Cohn's insistence the studio signed The Three Stooges in 1934. MGM had let the Stooges go but kept straight-man Ted Healy. The Stooges made 190 shorts for Columbia between 1934 and 1957. Columbia's short-subject department employed many famous comedians, including Buster Keaton, Charley Chase, Harry Langdon, and Hugh Herbert. Almost 400 of Columbia's 529 two-reel comedies were released to television between 1958 and 1961; and have since been released to home video.

In the early 1930s, Columbia distributed Walt Disney's famous Mickey Mouse cartoons. In 1933, the studio established its own animation house, under the Screen Gems brand. Columbia's leading cartoon series were Krazy Kat, Scrappy, The Fox and the Crow, and (very briefly) Li'l Abner. In 1949, Columbia agreed to release animated shorts from United Productions of America. These new shorts were more sophisticated than Columbia's older cartoons, and many won critical praise and industry awards.

According to Bob Thomas' book King Cohn, studio chief Harry Cohn always placed a high priority on serials. Beginning in 1937, Columbia entered the lucrative serial market, and kept making these episodic adventures until 1956, after other studios had discontinued them. The most famous Columbia serials are based on comic-strip or radio characters: Mandrake the Magician, The Shadow, Terry and the Pirates, Batman, and Superman, among many others.

Columbia also produced musical shorts, sports reels (usually narrated by sportscaster Bill Stern), and travelogues. Its 'Screen Snapshots' series, showing behind-the-scenes footage of Hollywood stars, was a Columbia perennial; producer-director Ralph Staub kept this series going through 1958.

Merle Oberon. Italian postcard by Rotalfoto, Milano, no. 46. Photo: Columbia C.E.I.A.D.

Burt Lancaster. Italian postcard by Bromofoto, no. 957. Photo: Columbia C.E.I.A.D.

Marta Toren. Italian postcard by B.F.F. Edit., no. 3048. Photo: Columbia C.E.I.A.D.

Vittorio Gassman. Italian postcard by Casa Editr. Ballerini & Fratini, Firenze (B.F.F. Edit.), no. 2962. Photo: Columbia C.E.I.A.D.

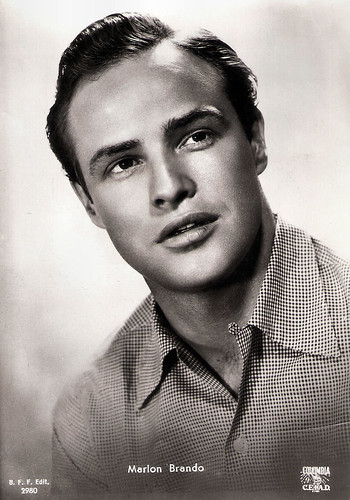

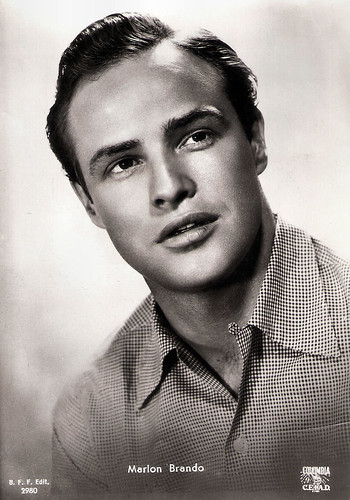

Marlon Brando. Italian postcard by B.F.F. Edit., no. 2980. Photo: Columbia C.E.I.A.D.

In the 1940s, Columbia propelled in part by their film's surge in audiences during the war, and also benefited from the popularity of its biggest star, Rita Hayworth. Columbia maintained a long list of contractees well into the 1950s: Glenn Ford, William Holden, Judy Holliday, The Three Stooges, Ann Miller, Jack Lemmon, Adele Jergens, Lucille Ball, Kerwin Mathews, Kim Novak, and others.

Harry Cohn monitored the budgets of his films, and the studio got the maximum use out of costly sets, costumes, and props by reusing them in other films. Many of Columbia's low-budget B-films and short subjects have an expensive look, thanks to Columbia's efficient recycling policy. Cohn was reluctant to spend lavish sums on even his most important pictures, and it was not until 1943 that he agreed to use three-strip Technicolor in a live-action feature.

Columbia's first Technicolor feature was the Western The Desperadoes, starring Randolph Scott and Glenn Ford. Cohn quickly used Technicolor again for Cover Girl (Charles Vidor, 1944), a Hayworth vehicle that instantly was a smash hit, and for the fanciful biography of Frédéric Chopin, A Song to Remember (Charles Vidor, 1945), with Cornel Wilde and Merle Oberon. Another biopic, The Jolson Story (Alfred E. Green, 1946) with Larry Parks, was started in black-and-white, but when Cohn saw how well the project was proceeding, he scrapped the footage and insisted on filming in Technicolor.

In 1948, the United States v. Paramount Pictures, Inc. anti-trust decision forced Hollywood motion picture companies to divest themselves of the theatre chains that they owned. Since Columbia did not own any theatres, it was now on equal terms with the largest studios, and soon replaced RKO on the list of the Big Five studios.

By 1950, Columbia had discontinued most of its popular series films like Boston Blackie, Blondie, The Lone Wolf, etc. Only Jungle Jim featuring Johnny Weissmuller, launched by producer Sam Katzman in 1949, kept going through 1955. Katzman contributed greatly to Columbia's success by producing dozens of topical feature films, including crime dramas, Science-Fiction stories, and Rock-'n'-Roll musicals. Columbia kept making serials until 1956 and two-reel comedies until 1957, after other studios had abandoned them.

Rita Hayworth. Italian postcard by Bromofoto, no. 284.

Rita Hayworth. Dutch postcard, Col. Int., no. 286. Photo: Columbia. Publicity still for Cover Girl (Charles Vidor, 1944).

Rita Hayworth. Spanish postcard, no. 4026. Photo: Robert Coburn / Columbia Pictures. Publicity still for Gilda (Charles Vidor, 1946).

Rita Hayworth. Vintage card by IBIS, no. 23. Photo: Robert Coburn / Columbia Pictures. Publicity still for Gilda (Charles Vidor, 1946). Costume by Jean Louis.

Rita Hayworth. German postcard by F.J. Rüdel Filmpostkartenverlag, Hamburg-Bergedorf, no. 423. Photo: Columbia. Publicity still for Affair in Trinidad (Vincent Sherman, 1952).

As the larger studios declined in the 1950s, Columbia's position improved. This was largely because it did not suffer from the massive loss of income that the other major studios suffered from losing their theatres. Columbia backed various independent producers and directors, among them Elia Kazan, Fred Zinnemann, David Lean, Robert Rossen, Otto Preminger, and Joseph Losey.

The studio continued to produce 40-plus pictures a year, offering productions that often broke ground and kept audiences coming to cinemas such as its adaptation of the controversial James Jones novel, From Here to Eternity (Fred Zinnemann, 1953) with Burt Lancaster, On the Waterfront (Elia Kazan, 1954) with Marlon Brando, and The Bridge on the River Kwai (David Lean, 1957) with William Holden, Jack Hawkins and Alec Guinness. All three films won the Best Picture Oscar.

Columbia president Harry Cohn died of a heart attack in February 1958. By 1966, the studio was suffering from box-office failures, and takeover rumours began surfacing. After turning down releasing Albert R. Broccoli's Eon Productions James Bond films, Columbia had hired Broccoli's former partner Irving Allen to produce the Matt Helm series with Dean Martin. Columbia also produced a James Bond spoof, Casino Royale (Val Guest, a.o., 1967), in conjunction with Charles K. Feldman, which held the adaptation rights for that novel. The studio also offered old-fashioned fare like A Man for All Seasons (Fred Zinnemann, 1966) and Oliver! (Carol Reed, 1968).

Columbia came back with the more contemporary Easy Rider (Dennis Hopper, 1969) with Peter Fonda, Five Easy Pieces (Bob Rafelson, 1970) starring Jack Nicholson, and The Last Picture Show (Peter Bogdanovich, 1971). During the 1970s, the studio re-emerged with hits like Close Encounters of the Third Kind (Steven Spielberg, 1977), Tootsie (Sydney Pollack, 1982), and Gandhi (Richard Attenborough, 1982). Columbia was purchased by The Coca-Cola Company in 1982. That same year, Columbia helped launch a new motion-picture studio, Tri-Star Pictures, which was merged with Columbia in 1987 to form Columbia Pictures Entertainment, Inc. In 1989 Columbia was acquired by the Sony Corporation of Japan.

The Columbia Pictures logo, featuring a woman carrying a torch and wearing a drape (representing Columbia, a personification of the United States), has gone through five major revisions. Originally in 1924, Columbia Pictures used a logo featuring a female Roman soldier holding a shield in her left hand and a stick of wheat in her right hand. The logo changed in 1928 with the woman wearing a draped flag and torch. The woman wore the stole and carried the palla of ancient Rome, and above her were the words A Columbia Production. The current logo was created in 1992, when Scott Mednick was hired by Peter Guber to create logos for all the entertainment properties then owned by Sony Pictures. Mednick hired New Orleans artist Michael Deas, to digitally repaint the logo and return the woman to her a classic look.

Maureen O'Hara. Dutch postcard by Gebr. Spanjersberg N.V., Rotterdam, no. 2028. Photo: Columbia Film / Ufa.

Gloria Grahame. German postcard by Kolibri-Verlag, no. 032. Photo: Columbia. Publicity still for The Glass Wall (Maxwell Shane, 1953).

Ursula Thiess. German postcard by Kolibri-Verlag, no. 1240. Photo: Columbia. Publicity still for The Iron Glove (William Castle, 1954).

Jack Hawkins. Dutch postcard by Uitg. Takken, Utrecht, no. 8304. Photo: Columbia. Publicity still for The Bridge on the River Kwai (David Lean, 1957).

Jean Seberg. German postcard by WS-Druck, Wanne-Eickel, no. 334. Photo: Columbia / Filmpress Zürich.

Sources: Aurora (Once upon a screen), Encyclopaedia Britannica, Wikipedia and IMDb.

Rita Hayworth. Belgian postcard by Victoria, Brussels, no. 639. Photo: Columbia Pictures.

Cary Grant. British postcard in the Picturegoer Series, London, no. 735c. Photo: Columbia.

Adele Jergens. British postcard in Picturegoer Series, London, no. W 643. Photo: Columbia.

Claudette Colbert. Dutch postcard by J.S.A.. Photo: Columbia. Publicity still for Tomorrow is Forever (Irving Pichel, 1946).

Burt Lancaster. German postcard by Franz Josef Rüdel, Filmpostkartenverlag, Hamburg-Bergedorf, no. 858. Photo: Columbia-Film. Publicity still for From Here to Eternity (Fred Zinnemann, 1953).

The Corned Beef and Cabbage Studio

Columbia was founded in June 1918 as Cohn-Brandt-Cohn (CBC) Film Sales by brothers Jack and Harry Cohn and Jack's best friend Joe Brandt. Jack had worked for Carl Laemmle at Universal, Joe had been Laemmle’s executive secretary and Jack’s younger brother Harry, had also worked at Universal.They released their first feature film in August 1922. Brandt was president of CBC Film Sales, handling sales, marketing and distribution from New York along with Jack Cohn, while Harry Cohn ran production in Hollywood.

The studio's early productions were low-budget short subjects: 'Screen Snapshots', the 'Hall Room Boys' (the vaudeville duo of Edward Flanagan and Neely Edwards), and the Chaplin imitator Billy West. The start-up CBC leased space in a Poverty Row studio on Hollywood's famously low-rent Gower Street. Among Hollywood's elite, the studio's small-time reputation led some to joke that CBC stood for 'Corned Beef and Cabbage'. Brandt eventually tired of dealing with the Cohn brothers, and he sold his one-third stake to Harry Cohn, who took over as president.

In an effort to improve its image, the Cohn brothers renamed the company Columbia Pictures Corporation in 1924. Cohn remained head of production as well, thus concentrating enormous power in his hands. He would run Columbia for the next 34 years, the second-longest tenure of any studio chief, behind only Warner Bros.' Jack L. Warner. Even in an industry rife with nepotism, Columbia was particularly notorious for having a number of Harry and Jack's relatives in high positions. Humorist Robert Benchley called it the Pine Tree Studio, "because it has so many Cohns".

Columbia's product line consisted mostly of moderately budgeted features and short subjects including comedies, sports films, various serials, and cartoons. Columbia gradually moved into the production of higher-budget fare, eventually joining the second tier of Hollywood studios along with United Artists and Universal. Like United Artists and Universal, Columbia was a horizontally integrated company. It controlled production and distribution; it did not own any theatres.

Helping Columbia's climb was the arrival of an ambitious director, Frank Capra. Between 1927 and 1939, Capra constantly pushed Cohn for better material and bigger budgets. A string of hits he directed in the early and mid 1930s solidified Columbia's status as a major studio. In particular, It Happened One Night (Frank Capra, 1934) with Clark Gable and Claudette Colbert put Columbia on the map. It won the Academy Award for Best Film of 1934.

Until then, Columbia's very existence had depended on theatre owners willing to take its films, since as mentioned above it didn't have a theatre network of its own. Other Capra-directed hits followed, including Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (Frank Capra, 1936), the original version of Lost Horizon (Frank Capra, 1937) with Ronald Colman, You Can’t Take it With You (Frank Capra, 1938), which was Capra's highest-grossing picture at Columbia, and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (Frank Capra, 1939), which made James Stewart a major star.

Capra but also Howard Hawks and others made some of the finest screwball comedies of the 1930s for Columbia: The Awful Truth (Leo McCarey, 1937), Holiday (George Cukor, 1938), and His Girl Friday (Howard Hawks, 1940), all starring Cary Grant. After Capra’s departure in 1939, Columbia languished because leading directors were reluctant to work for the notoriously hard-driving and vulgar Cohn.

In 1938, the addition of B. B. Kahane as Vice President would produce Charles Vidor's Those High Gray Walls (Charles Vidor, 1939), and The Lady in Question (Charles Vidor, 1940), the first joint film of Rita Hayworth and Glenn Ford. Kahane would later become the President of Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in 1959, until his death a year later.

Tullio Carminati and Grace Moore. British postcard in the Film Partners Series, London, no. P 151. Photo: Columbia. Publicity still for One Night of Love (Victor Schertzinger, 1934).

Claudette Colbert. Italian postcard by Rizzoli, Milano, 1937. Photo: Columbia.

Ronald Colman and Jane Wyatt. Italian postcard by Vecchioni & Guadagno, Roma. Photo: Columbia EIA. Publicity still for Lost Horizon (Frank Capra, 1937).

Marie McDonald. Dutch postcard by J.S.A. Photo: Columbia.

Sonja Henie. Dutch Postcard by J.S.A. Photo: Columbia F.B. / M.P.E.

Hollywood's Siberia for the less obedient stars

Columbia could not afford to keep a huge roster of contract stars, so Cohn usually borrowed them from other studios. At Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, the industry's most prestigious studio, Columbia was nicknamed 'Siberia, as Louis B. Mayer would use the loan out to Columbia as a way to punish his less-obedient signings. In the 1930s, Columbia signed Jean Arthur to a long-term contract, and after The Whole Town's Talking (John Ford, 1935), Arthur became a major comedy star. Ann Sothern's career was launched when Columbia signed her to a contract in 1936. Cary Grant signed a contract in 1937 and soon after it was altered to a non-exclusive contract shared with RKO.

Many theatres relied on Westerns to attract big weekend audiences, and Columbia always recognised this market. Its first cowboy star was Buck Jones, who signed with Columbia in 1930 for a fraction of his former big-studio salary. Over the next two decades Columbia released scores of outdoor adventures with Jones, Tim McCoy, Ken Maynard, Robert (Tex) Allen, and Gene Autry. Columbia's most popular cowboy was Charles Starrett, who signed with Columbia in 1935 and starred in 131 western features over 17 years.

At Harry Cohn's insistence the studio signed The Three Stooges in 1934. MGM had let the Stooges go but kept straight-man Ted Healy. The Stooges made 190 shorts for Columbia between 1934 and 1957. Columbia's short-subject department employed many famous comedians, including Buster Keaton, Charley Chase, Harry Langdon, and Hugh Herbert. Almost 400 of Columbia's 529 two-reel comedies were released to television between 1958 and 1961; and have since been released to home video.

In the early 1930s, Columbia distributed Walt Disney's famous Mickey Mouse cartoons. In 1933, the studio established its own animation house, under the Screen Gems brand. Columbia's leading cartoon series were Krazy Kat, Scrappy, The Fox and the Crow, and (very briefly) Li'l Abner. In 1949, Columbia agreed to release animated shorts from United Productions of America. These new shorts were more sophisticated than Columbia's older cartoons, and many won critical praise and industry awards.

According to Bob Thomas' book King Cohn, studio chief Harry Cohn always placed a high priority on serials. Beginning in 1937, Columbia entered the lucrative serial market, and kept making these episodic adventures until 1956, after other studios had discontinued them. The most famous Columbia serials are based on comic-strip or radio characters: Mandrake the Magician, The Shadow, Terry and the Pirates, Batman, and Superman, among many others.

Columbia also produced musical shorts, sports reels (usually narrated by sportscaster Bill Stern), and travelogues. Its 'Screen Snapshots' series, showing behind-the-scenes footage of Hollywood stars, was a Columbia perennial; producer-director Ralph Staub kept this series going through 1958.

Merle Oberon. Italian postcard by Rotalfoto, Milano, no. 46. Photo: Columbia C.E.I.A.D.

Burt Lancaster. Italian postcard by Bromofoto, no. 957. Photo: Columbia C.E.I.A.D.

Marta Toren. Italian postcard by B.F.F. Edit., no. 3048. Photo: Columbia C.E.I.A.D.

Vittorio Gassman. Italian postcard by Casa Editr. Ballerini & Fratini, Firenze (B.F.F. Edit.), no. 2962. Photo: Columbia C.E.I.A.D.

Marlon Brando. Italian postcard by B.F.F. Edit., no. 2980. Photo: Columbia C.E.I.A.D.

Columbia's efficient recycling policy

In the 1940s, Columbia propelled in part by their film's surge in audiences during the war, and also benefited from the popularity of its biggest star, Rita Hayworth. Columbia maintained a long list of contractees well into the 1950s: Glenn Ford, William Holden, Judy Holliday, The Three Stooges, Ann Miller, Jack Lemmon, Adele Jergens, Lucille Ball, Kerwin Mathews, Kim Novak, and others.

Harry Cohn monitored the budgets of his films, and the studio got the maximum use out of costly sets, costumes, and props by reusing them in other films. Many of Columbia's low-budget B-films and short subjects have an expensive look, thanks to Columbia's efficient recycling policy. Cohn was reluctant to spend lavish sums on even his most important pictures, and it was not until 1943 that he agreed to use three-strip Technicolor in a live-action feature.

Columbia's first Technicolor feature was the Western The Desperadoes, starring Randolph Scott and Glenn Ford. Cohn quickly used Technicolor again for Cover Girl (Charles Vidor, 1944), a Hayworth vehicle that instantly was a smash hit, and for the fanciful biography of Frédéric Chopin, A Song to Remember (Charles Vidor, 1945), with Cornel Wilde and Merle Oberon. Another biopic, The Jolson Story (Alfred E. Green, 1946) with Larry Parks, was started in black-and-white, but when Cohn saw how well the project was proceeding, he scrapped the footage and insisted on filming in Technicolor.

In 1948, the United States v. Paramount Pictures, Inc. anti-trust decision forced Hollywood motion picture companies to divest themselves of the theatre chains that they owned. Since Columbia did not own any theatres, it was now on equal terms with the largest studios, and soon replaced RKO on the list of the Big Five studios.

By 1950, Columbia had discontinued most of its popular series films like Boston Blackie, Blondie, The Lone Wolf, etc. Only Jungle Jim featuring Johnny Weissmuller, launched by producer Sam Katzman in 1949, kept going through 1955. Katzman contributed greatly to Columbia's success by producing dozens of topical feature films, including crime dramas, Science-Fiction stories, and Rock-'n'-Roll musicals. Columbia kept making serials until 1956 and two-reel comedies until 1957, after other studios had abandoned them.

Rita Hayworth. Italian postcard by Bromofoto, no. 284.

Rita Hayworth. Dutch postcard, Col. Int., no. 286. Photo: Columbia. Publicity still for Cover Girl (Charles Vidor, 1944).

Rita Hayworth. Spanish postcard, no. 4026. Photo: Robert Coburn / Columbia Pictures. Publicity still for Gilda (Charles Vidor, 1946).

Rita Hayworth. Vintage card by IBIS, no. 23. Photo: Robert Coburn / Columbia Pictures. Publicity still for Gilda (Charles Vidor, 1946). Costume by Jean Louis.

Rita Hayworth. German postcard by F.J. Rüdel Filmpostkartenverlag, Hamburg-Bergedorf, no. 423. Photo: Columbia. Publicity still for Affair in Trinidad (Vincent Sherman, 1952).

Backing independent producers and directors

As the larger studios declined in the 1950s, Columbia's position improved. This was largely because it did not suffer from the massive loss of income that the other major studios suffered from losing their theatres. Columbia backed various independent producers and directors, among them Elia Kazan, Fred Zinnemann, David Lean, Robert Rossen, Otto Preminger, and Joseph Losey.

The studio continued to produce 40-plus pictures a year, offering productions that often broke ground and kept audiences coming to cinemas such as its adaptation of the controversial James Jones novel, From Here to Eternity (Fred Zinnemann, 1953) with Burt Lancaster, On the Waterfront (Elia Kazan, 1954) with Marlon Brando, and The Bridge on the River Kwai (David Lean, 1957) with William Holden, Jack Hawkins and Alec Guinness. All three films won the Best Picture Oscar.

Columbia president Harry Cohn died of a heart attack in February 1958. By 1966, the studio was suffering from box-office failures, and takeover rumours began surfacing. After turning down releasing Albert R. Broccoli's Eon Productions James Bond films, Columbia had hired Broccoli's former partner Irving Allen to produce the Matt Helm series with Dean Martin. Columbia also produced a James Bond spoof, Casino Royale (Val Guest, a.o., 1967), in conjunction with Charles K. Feldman, which held the adaptation rights for that novel. The studio also offered old-fashioned fare like A Man for All Seasons (Fred Zinnemann, 1966) and Oliver! (Carol Reed, 1968).

Columbia came back with the more contemporary Easy Rider (Dennis Hopper, 1969) with Peter Fonda, Five Easy Pieces (Bob Rafelson, 1970) starring Jack Nicholson, and The Last Picture Show (Peter Bogdanovich, 1971). During the 1970s, the studio re-emerged with hits like Close Encounters of the Third Kind (Steven Spielberg, 1977), Tootsie (Sydney Pollack, 1982), and Gandhi (Richard Attenborough, 1982). Columbia was purchased by The Coca-Cola Company in 1982. That same year, Columbia helped launch a new motion-picture studio, Tri-Star Pictures, which was merged with Columbia in 1987 to form Columbia Pictures Entertainment, Inc. In 1989 Columbia was acquired by the Sony Corporation of Japan.

The Columbia Pictures logo, featuring a woman carrying a torch and wearing a drape (representing Columbia, a personification of the United States), has gone through five major revisions. Originally in 1924, Columbia Pictures used a logo featuring a female Roman soldier holding a shield in her left hand and a stick of wheat in her right hand. The logo changed in 1928 with the woman wearing a draped flag and torch. The woman wore the stole and carried the palla of ancient Rome, and above her were the words A Columbia Production. The current logo was created in 1992, when Scott Mednick was hired by Peter Guber to create logos for all the entertainment properties then owned by Sony Pictures. Mednick hired New Orleans artist Michael Deas, to digitally repaint the logo and return the woman to her a classic look.

Maureen O'Hara. Dutch postcard by Gebr. Spanjersberg N.V., Rotterdam, no. 2028. Photo: Columbia Film / Ufa.

Gloria Grahame. German postcard by Kolibri-Verlag, no. 032. Photo: Columbia. Publicity still for The Glass Wall (Maxwell Shane, 1953).

Ursula Thiess. German postcard by Kolibri-Verlag, no. 1240. Photo: Columbia. Publicity still for The Iron Glove (William Castle, 1954).

Jack Hawkins. Dutch postcard by Uitg. Takken, Utrecht, no. 8304. Photo: Columbia. Publicity still for The Bridge on the River Kwai (David Lean, 1957).

Jean Seberg. German postcard by WS-Druck, Wanne-Eickel, no. 334. Photo: Columbia / Filmpress Zürich.

Sources: Aurora (Once upon a screen), Encyclopaedia Britannica, Wikipedia and IMDb.

No comments:

Post a Comment