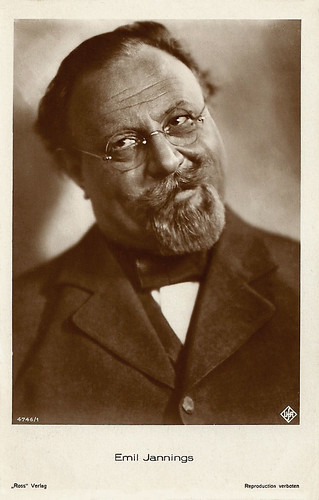

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 4746/1, 1929-1930. Photo: Ufa. Emil Jannings in Der blaue Engel/The Blue Angel (Josef von Sternberg, 1930).

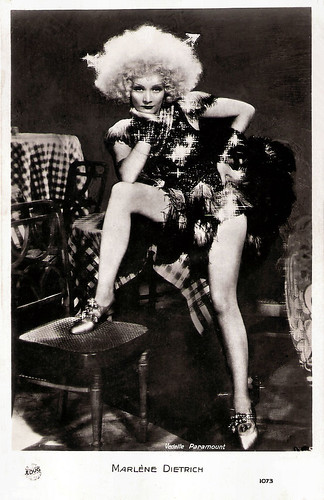

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 5125/1, 1930-1931. Photo: Ufa. Marlene Dietrich in Der blaue Engel/The Blue Angel (Josef von Sternberg, 1930) Collection: Marlene Pilaete.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 5751/1, 1930-1931. Photo: Paramount. Gary Cooper in Morocco (Josef von Sternberg, 1930). Caption: Garry Cooper (sic).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 6673/2, 1931-1932. Photo: Don English / Paramount. Marlene Dietrich in Shanghai Express (Josef von Sternberg, 1932).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 8995/1, 1933-1934. Photo: Paramount. Marlene Dietrich in The Devil is a Woman (Josef von Sternberg, 1935).

A symphony of shadows and lighting effects

Josef von Sternberg was born as Jonas Sternberg in 1894, in Vienna, at that time part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Sternberg was the son of Moses Sternberg, an impoverished Jewish businessman from Krakow and former soldier in the army of Austria-Hungary, and his wife Serafine, née Singer. The family moved to the U.S. in 1901. Jonas attended public school until the family, except Moses, returned to Vienna three years later. Throughout his life, Sternberg carried vivid memories of Vienna and nostalgia for some of his happiest childhood moments.

In 1908, when Jonas was fourteen, he returned with his mother to Queens, New York, and settled in the United States. He acquired American citizenship in 1908. After a year, he stopped attending Jamaica High School and began working in various occupations, including millinery apprentice, door-to-door trinket salesman and stock clerk at a lace factory. At the age of 17, he started to work at the World Film Company in Fort Lee, New Jersey, as a film repairer and projectionist under the stage name Josef Sternberg. In 1914, when the company was purchased by actor and film producer William A. Brady, Sternberg rose to chief assistant, responsible for writing (inter)titles and editing films to cover lapses in continuity for which he received his first official film credits.

When the United States entered World War I in 1917, he joined the US Army and was assigned to the Signal Corps headquartered in Washington, D.C., where he photographed training films for recruits. Shortly after the war, Sternberg left Brady's Fort Lee operation and worked for various studios. Sternberg travelled widely in Europe between 1922 and 1924, where he worked for the short-lived Alliance Film Corporation in London, on such films as The Bohemian Girl (Harley Knoles, 1922).

When he returned to California in 1924, he started as an assistant to director Roy William Neill's Vanity's Price. Sternberg's aptitude for effective directing was recognized in his handling of the operating room scene, singled out for special mention by New York Times critic Mordaunt Hall. Through the agency of Charles Chaplin and Mary Pickford, he met the German writer and screenwriter Karl Gustav Vollmoeller, who invited him to Venice and Berlin in 1925 and introduced him to the actor Emil Jannings.

With actor George K. Arthur, he made The Salvation Hunters (1925) for only US $4,800, which was filmed on a large steam dredge in the marshes near San Pedro Bay. It depicted three young drifters who struggle to survive in a dystopian landscape. The film caught the attention of some critics who praised Sternberg's innovative use of light and shadow in the dramatisation of a scene. Plans to make a film with Mary Pickford subsequently fell through, but in the end von Sternberg was offered a contract by MGM.

Signing an eight-film agreement with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer in 1925, Sternberg entered into the increasingly rigid studio system at MGM, and the cooperation with the studio executives and the stars was not easy. During the shooting of The Masked Bride (1925), Von Sternberg, who was notorious for being autocratic, argued violently with the leading actress Mae Murray for weeks. Eventually the contract was terminated by mutual agreement and the film was directed by Christy Cabanne.

A short time later he received an offer by Charles Chaplin to make the film A Woman of the Sea/The Sea Gull (Josef von Sternberg, 1926) as a comeback vehicle for Edna Purviance, Chaplin's former leading lady. However, Chaplin decided not to distribute the finished film as he considered it a "highly visual, almost Expressionistic" work, completely lacking in the humanism that he had anticipated". In the 1930s, Chaplin had the negative destroyed in order to be able to deduct the filming costs from his taxes.

The tide turned for Von Sternberg when he got a contract with Paramount in 1927. After he had successfully re-produced some scenes for films that had already been shot, such as Children of Divorce (Frank Lloyd, 1927), with Clara Bow, he got the chance to shoot the film Underworld later that year. The script about Chicago gangsters by journalist Ben Hecht took a concerned look behind the scenes of organised crime for the first time and Von Sternberg turned it into a gripping gangster film. At the same time, he composed scenes out of light and shadow that prompted one critic to remark that von Sternberg used the camera the way a painter uses his brush. The film was an enormous box-office hit and Academy Award winner for Best Original Story.

After this overwhelming commercial success, Paramount gave Von Sternberg a free hand with the direction of The Last Command (Josef von Sternberg, 1928), which was shot with Emil Jannings, the studio's most valuable star. A year later, Jannings won the Oscar in the Best Actor in a Leading Role category for hhis performance, the first actor to do so. In the same year followed the drama The Docks of New York (Josef von Sternberg, 1928) starring George Bancroft, Betty Compson, and Olga Baclanova, one of the most mature and visually beautiful films of his career. The story about a sailor and a prostitute was transformed by Von Sternberg into a symphony of shadows and lighting effects.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, Foreign, no. 99/1. Photo: Paramount. Emil Jannings in The Last Command (Josef von Sternberg, 1928).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 99/6. Photo: Paramount. Evelyn Brent and Emil Jannings in The Last Command (Josef von Sternberg, 1928).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 3946, 1928-1929. Photo: Paramount. Olga Baclanova in The Docks of New York (Josef von Sternberg, 1928). Collection: Didier Hanson.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 3993/1, 1928-1929. Photo: Paramount. Fay Wray in Street of Sin (Mauritz Stiller, Josef von Sternberg uncredited, 1928).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 4329/1, 1929-1930. Photo: Paramount. Esther Ralston in The Case of Lena Smith (Josef von Sternberg, 1929).

The eternal seductress

In 1929, Josef von Sternberg went to Germany to film the first sound film with star Emil Jannings at Paramount'sister studio Ufa. The contract with Ufa was brokered by Karl Gustav Vollmoeller, who was placed at his side by Ufa as screenwriter, technical advisor and general editor. It was also thanks to him that the film rights of the novel 'Professor Unrat' by Heinrich Mann were sold to Ufa under the title Der blaue Engel/The Blue Angel (Josef von Sternberg, 1930). The female lead was initially to be given to a wide variety of actresses, including Louise Brooks. But in the end the choice fell on Marlene Dietrich as Lola Lola, the nemesis of Emil Jannings's character Professor Immanuel Rath. Sternberg's romantic infatuation with his new star created difficulties on and off the set. Jannings strenuously objected to Sternberg's lavish attention to Dietrich's performance, at the elder actor's expense. Dietrich became an international star overnight.

The director and his new star left for America the same evening as the premiere, where they began shooting Morocco (Josef von Sternberg, 1930) with Gary Cooper. Dietrich was built up by the studio as an answer to Greta Garbo, but Von Sternberg turned the actress into a screen personality all her own over the course of their six Hollywood films together: Morocco (1930), Dishonored (1931), Shanghai Express (1932), Blonde Venus (1932), The Scarlet Empress (1934), and The Devil is a Woman (1935). Wikipedia: "The stories are typically set in exotic locales including Saharan Africa, World War I Austria, revolutionary China, Imperial Russia, and fin-de-siècle Spain. Sternberg's 'outrageous aestheticism' is on full display in these richly stylized works, both in technique and scenario."

However, von Sternberg was quickly accused by the press of paying too much attention to the visual aspects and staging of his leading lady and placing too little emphasis on a good script. Especially the film Blonde Venus (Josef von Sternberg, 1932), which they made immediately after their biggest financial success Shanghai Express (Josef von Sternberg, 1932), made Von Sternberg's implied weaknesses clear. Marlene Dietrich, who finally wanted a change of role, away from the eternal seductress, demanded material that showed her as a caring wife and good mother. Von Sternberg, however, did not like the concept and also showed Dietrich as a cabaret star. At no point was there a coherent script and in the end, according to critics, only the musical scenes were convincing, such as the famous 'hot voodoo' number in which Dietrich first comes on stage dressed as a gorilla and then peels herself out of the costume.

In 1931, the director took over a half-finished script that Sergei Eisenstein had written based on the social novel 'An American Tragedy' by Theodore Dreiser before he was forced out of the project. Von Sternberg discarded most of the ideas and started from scratch. The result, An American Tragedy (Josef von Sternberg, 1931), a tale of a sexually obsessed middle-class youth (Phillips Holmes) whose deceptions lead to the death of a poor factory girl (Sylvia Sidney), divided critics like few of his previous works. On the one hand, they praised the already familiar compositions of light and shadow and the performance of Sylvia Sidney as Drina. But overall the consensus was that Dreiser's biting social commentary and Von Sternberg's more lyrical narrative style were mutually exclusive.

After Marlene Dietrich, under pressure from the studio and against the backdrop of the less than encouraging box office results of Blonde Venus (Josef von Sternberg, 1932), had made the less than successful film Song of Songs (Rouben Mamoulian, 1933), the two artists reunited in mid-1934. In response to the very successful film Queen Christina (Rouben Mamoulian, 1933), which showed Garbo as the Swedish queen a year earlier, Paramount wanted to present its own glamour star as a famous ruler as well. Thus, under Sternberg's direction, the historical film The Scarlet Empress (Josef von Sternberg, 1934) was made with Dietrich as Catherine the Great. During the filming, which was again marked by endless changes to the script, and amid escalating production costs.

The Von Sternberg-Dietrich collaboration ended the following year with The Devil is a Woman (Josef von Sternberg, 1935), a story about a Spanish dancer. In this final tribute he sets forth his reflections on their five-year professional and personal association. Based on a novel by Pierre Louÿs, 'La Femme et le pantin' (The Woman and the Puppet, 1908), the drama unfolds in Spain's famous carnival at the end of the 19th century. A love triangle develops pitting the young revolutionary Antonio (Cesar Romero) against the middle-aged former military officer Don Pasqual (Lionel Atwill) in a contest for the love of the devastatingly beautiful demi-mondaine Concha (Dietrich). Despite the gaiety of the setting, the film has a dark, brooding, reflective quality. Dietrich liked the film more than any other because, because he made her look so beautiful. However, the film was a disaster financially.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 5126/1, 1930-1931. Photo: Eugene Robert Richee / Paramount. Marlene Dietrich in Morocco (Josef von Sternberg, 1930). Collection: Marlene Pilaete.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 5964/3, 1930-1931. Photo: Paramount. Marlene Dietrich in Dishonored/Agent X27 (Josef von Sternberg, 1931). Collection: Geoffrey Donaldson Institute.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 5968/1, 1930-1931. Paramount. Marlene Dietrich in Dishonored/Agent X27 (Josef von Sternberg, 1931).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 6379/2. Photo: Paramount. Marlene Dietrich as Shanghai Lily and Clive Brook as 'Doc' Harvey in Shanghai Express (Josef von Sternberg, 1932).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 8497/1, 1933-1934. Photo: Paramount. John Lodge and Marlene Dietrich in The Scarlet Empress (Josef von Sternberg, 1934). Collection: Marlene Pilaete.

A shoot that turned into a disaster

In 1935, after the financial failures of The Scarlet Empress and The Devil is a Woman, Josef von Sternberg moved to Columbia Pictures, where he made Crime and Punishment (Josef von Sternberg, 1935), an adaption of the 19th-century Russian novelist Fyodor Dostoevsky's novel starring Peter Lorre. The film was shown this year at Il Cinema Ritrovato 2022 and Ehsan Khoshbakht writes in the festival catalogue: "Sternberg uses intense closeups of a profusely sweating Lorre (already hooked on drugs in real life) to show his further drift into mental instability. But unlike with other adaptations the director doesn’t care much about the moral dilemmas central to Dostoevsky’s work. Sternberg is a man of surfaces, the outer appearance of the world, and never delves into Raskolnikov’s delirious vision. As a result, the film confused and angered reviewers upon its release. Today, the same restraint has become the film’s main strength."

Sternberg's next feature was The King Steps Out (Josef von Sternberg, 1936), based on Fritz Kreisler's 'Sissi', an operetta about the life of Empress Elisabeth of Austria and starring soprano Grace Moore. The production was undermined by personal and professional discord between opera diva and director. Sternberg found himself unable to identify himself with his leading lady or adapt his style to the demands of operetta. He left Columbia. The following year he was hired by Alexander Korda to film I, Claudius (Josef von Sternberg, 1937), but the shoot turned into a disaster. The leading actress Merle Oberon almost died in a traffic accident, the financing of the film fell through and in the end the production was cancelled. The few surviving scenes, however, are considered the best Von Sternberg ever shot.

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer asked Sternberg to finish up a few scenes for departing French director Julien Duvivier's The Great Waltz (1938). At the personal request of Louis B. Mayer, Von Sternberg was commissioned in 1938 to turn his Austrian discovery Hedy Lamarr into the biggest star in the world. The production of I Take This Woman (W.S. Van Dyke, 1940) soon turned into a full-blown disaster that lasted over 16 months, with almost the entire cast replaced and three directors taking turns. Eventually Von Sternberg found himself directing Wallace Beery in the police drama Sergeant Madden (Josef von Sternberg, 1939). The film is notable in that the theme and style strongly resemble German films of the post-WWI period. Despite some resistance from the bombastic Beery, Sternberg coaxed a relatively restrained performance that recalls Emil Jannings.

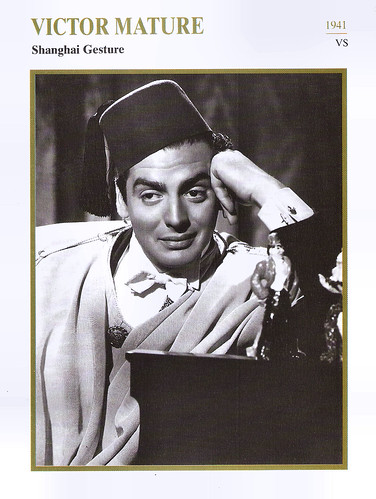

With the exception of Shanghai Gesture (Josef von Sternberg, 1941), which tells the story of Mother Gin Sling and her brothel (a casino in the film), and the drama The Saga of Anatahan (Josef von Sternberg, 1953), his later work did not have the level of his years at Paramount. Wikipedia calls Shanghai Gesture "a tour-de-force with Sternberg's sheer 'physical expressiveness' of his characters that conveys both emotion and motivation". The Japanese war drama Anatahan/The Saga of Anatahan told the true story of Japanese soldiers who held their position on the island of Anatahan for seven years after the end of the war because they refused to accept the Japanese surrender. Von Sternberg had an unusually high degree of control over the film, made outside the studio system, which allowed him to not only direct, but also write, photograph, and narrate the action.

Although Anatahan/The Saga of Anatahan opened modestly well in Japan, it did poorly in the US, where Von Sternberg continued to recut the film for four more years. He subsequently abandoned the project and went on to teach film at UCLA for most of the remainder of his lifetime. In 1963, Josef von Sternberg received the Filmband in Gold in Germany for his many years of outstanding work. Two years later, he presented his sardonic autobiography 'Fun in a Chinese Laundry' (1965) of which the title was drawn from an early film comedy.

Josef von Sternberg died in 1969 in a Los Angeles County hospital as a result of a heart attack. He was buried in Westwood Village Memorial Park Cemetery. He was married to film actress Riza Royce in his first marriage from 1926 to 1930. In 1945 he married Jean Avette McBride. The marriage was divorced in 1947. Von Sternberg was finally married to the art historian Meri Otis Wilner from 1948 until his death. From this marriage came his son Nicholas Josef von Sternberg, who was born in 1951.

French postcard by EDUG, no. 1073. Photo: Paramount. Marlene Dietrich in Blonde Venus (Josef von Sternberg, 1932).

French postcard, no. 34. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Fernand Gravey in The Great Waltz (Julien Duvivier, Josef von Sternberg uncredited, 1938).

Dutch collectors card in the Filmsterren: een Portret series by Edito Service S.A., 1996. Photo: United Artists / The Kobal Collection. Victor Mature in Shanghai Gesture (Josef von Sternberg, 1941).

Spanish postcard, 1953. Photo: Procines S.A. Gregory Peck and Jennifer Jones in Duel in the Sun (King Vidor, Josef von Sternberg uncredited, 1946).

German cigarette card in the series Unsere Bunten Filmbilder by Ross Verlag for Cigarettenfabrik Josetti, Berlin, no. 25. Photo: Paramount. Marlene Dietrich in The Devil is a Woman (Josef von Sternberg, 1935).

Sources: Ehsan Khoshbakht (Il Cinema Ritrovato), Wikipedia (German, Dutch and English) and IMDb.

No comments:

Post a Comment