Karl May (1842–1912) was one of Germany’s most widely read authors and a master storyteller whose adventure novels shaped popular images of the American West and the Orient for generations of European readers. Although he travelled little before late in life, his vivid imagination created enduring heroes such as Winnetou and Old Shatterhand. May’s tales proved equally powerful on screen. From the 1920s onwards, and especially during the 1960s boom of German Westerns, his stories inspired hugely successful films that left a lasting mark on European popular cinema.

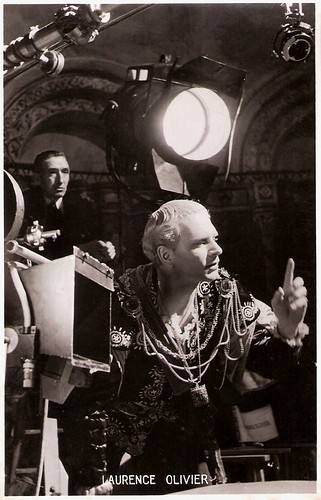

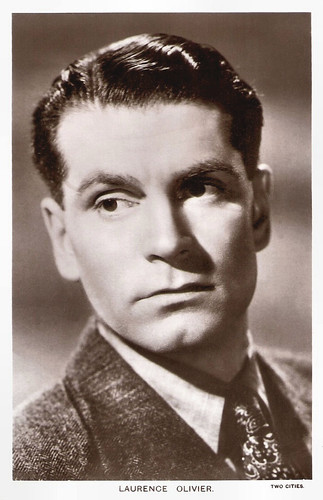

Dutch postcard by Facet Publishers, Lunteren, no. 4. Photo: Rank Film Distributors (Holland) N.V.

Pierre Brice and

Lex Barker in

Der Schatz im Silbersee (Harald Reinl, 1963).

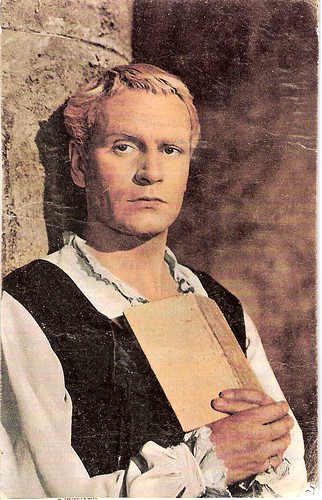

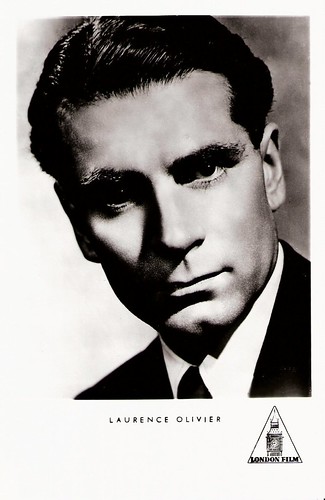

German postcard, no. E 21. Photo: Constantin.

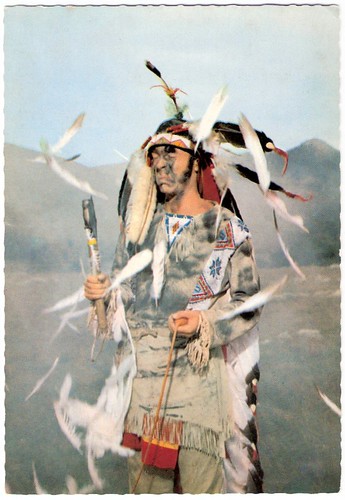

Chris Howland in

Winnetou I (Harald Reinl, 1963). Caption: "What do you do as a reporter when you get no Indian in front of your camera? You put on some make-up and make a self-portrait, here, unfortunately, it failed."

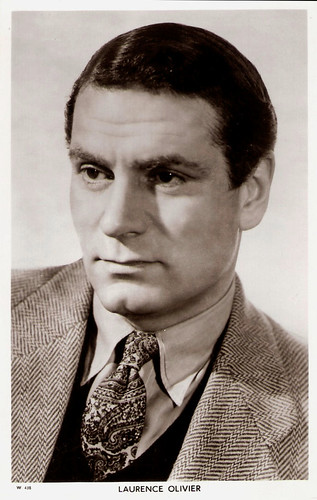

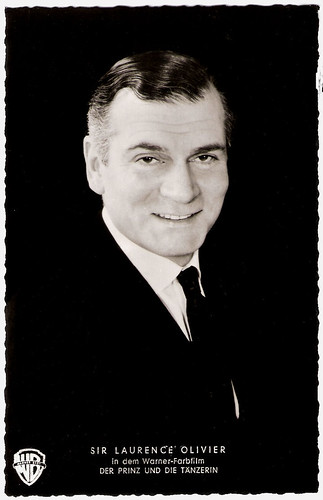

German postcard, no. E 22. Photo: Constantin.

Ralf Wolter in

Winnetou I (Harald Reinl, 1963). Caption: "The conquering Apaches decide in the powwow to kill the white prisoners. The cranky Sam Hawkens just can't understand why this is the way he has to go to the happy hunting ground."

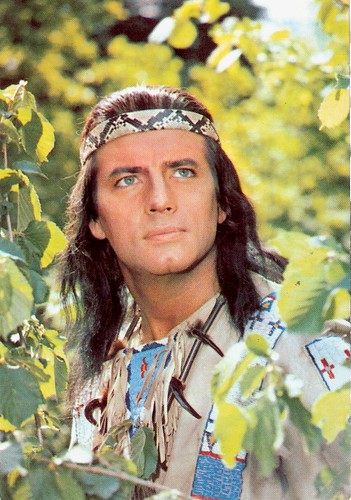

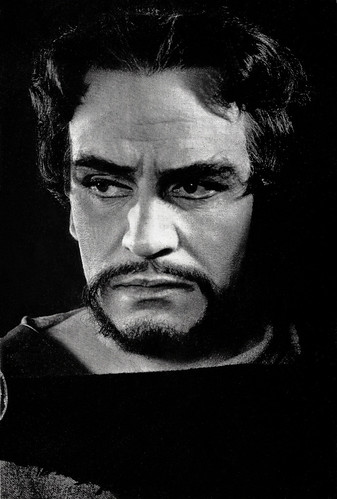

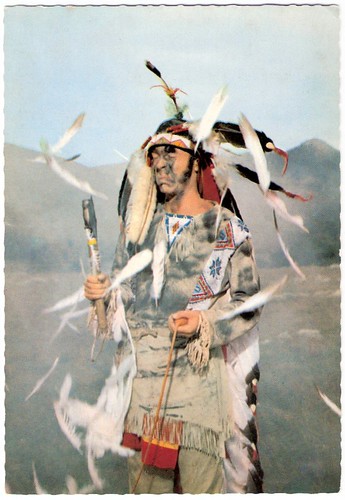

German postcard by Kruger. Photo: Bernard of Hollywood (Bruno Bernard) / CCC Produktion.

Pierre Brice as Winnetou in

Old Shatterhand (Hugo Fregonese, 1964).

German postcard by Kruger. Photo: Bernard of Hollywood (Bruno Bernard) / CCC-Produktion.

Lex Barker as Old Shatterhand in

Old Shatterhand (Hugo Fregonese, 1964).

From poverty to literary fame

Carl Friedrich May was born in 1842 in Ernstthal, then part of the Kingdom of Saxony. He was the fifth child of weaver

Heinrich May and his wife

Wilhelmina Weise. Nine of the thirteen other children in the poor family died at a young age. Shortly after his birth, he became blind due to a vitamin deficiency. During his blind childhood, his grandmother told him many fairy tales, which developed his imagination. At the age of four or five, after medical examination, he was given the right nutrients (vitamins A & D), after which he was able to see and walk. For this story, there is no evidence other than May's own statements.

In 1856,

Karl May began training as a teacher in Waldheim, Saxony. Here, in 1860, he was convicted of stealing six candles. In 1861, May passed his teaching exam. He was appointed as a teacher at the factory school in Altchemnitz. Here, on 26 December, he was convicted of theft. He took a watch, which he was allowed to borrow from a roommate during the day, home for the weekend, after which the roommate reported it. May was sentenced to imprisonment. He lost his job and his teaching licence. After this, May worked with little success as a private tutor, an author of tales, a composer and a public speaker. When he pretended to be a wealthy doctor in 1865, he was caught and sentenced to four years in prison. He was released early in 1868, but committed further thefts in various positions, for which he served a prison sentence in Waldheim from 1870 to 1874. During these difficult years, May became an administrator of the prison library, which gave him the chance to read travel literature, adventure stories and classical works, which later fed his fiction.

His life changed when he met the Catholic prison chaplain

Johannes Kochta in Waldheim. After his release, May returned to his parents in Ernstthal and began writing. From 1875 to 1878, May was appointed editor of the colportage weekly magazines

Der Beobachter an der Elbe and

Frohe Stunden. In the 1870s and 1880s, he published short adventure tales for magazines, often presenting them as first-person travel accounts. These magazines were owned by the Dresden publisher

Heinrich Gotthold Münchmeyer. This secured May's livelihood for the first time. May then began to publish some stories he had written himself. In 1876, May resigned because attempts were made to tie him permanently to the company by marrying Münchmeyer's sister-in-law, and because the publishing house had a bad reputation. After another job as an editor at Bruno Radelli's publishing house in Dresden, May became a freelance writer in 1878 and moved to Dresden with his girlfriend Emma Pollmer. However, his publications did not yet provide a regular income; there is evidence of May's rent arrears and other debts from In 1880, he married

Emma Pollmer, with whom he had been living for several years. Between 1881 and 1887, the first versions of his travel adventures appeared in 1992 as 'Durch die Wüste' (The Death Caravan), 'Durchs wilde Kurdistan' (Through Kurdistan) and 'Von Bagdad nach Stambul' (To Istanbul) in the Catholic family magazine

Deutscher Hausschatz. During this period, he also began work on a series of colportage novels for Munchmeyer.

In 1888,

Karl May was given a permanent position as an employee at the Stuttgart magazine

Der gute Kamerad. His breakthrough came with longer novels set in exotic locales, particularly the American West and the Middle East, written long before he had visited either region. May skilfully blended action, moral reflection and a strong sense of idealism, promoting themes of friendship, justice and intercultural understanding. From 1892 onwards, his travel stories appeared in increasingly large print runs. Most of his American novels are characterised by a Christian moralistic, romantic slant. Thanks to the good sales of his books, he was very successful. May conducted talking tours in Germany and Austria and allowed autographed cards to be printed.

In 1899-1900,

Karl May undertook his first trip to the Orient. In 1908, he also travelled to America, from where he brought back many original souvenirs from the daily life of various Native American tribes. In 1903, he divorced his wife and married his secretary,

Klara Plöhn. May began to see himself as a great writer, but his later works, such as 'Babel and the Bible', 'To the Land of the Silver Lion', and 'Peace on Earth', were not recognised.

Dutch postcard by Gebr. Spanjersberg N.V., Rotterdam/Edition Facet Publishers. Photo: Rank Film Publishers (Holland) N.V.

Pierre Brice as Winnetou and

Lex Barker as Old Shatterhand in

Der Schatz im Silbersee (Harald Reinl, 1962).

German postcard, no. E 61. Photo: Constantin.

Götz George in

Der Schatz im Silbersee / The Treasure of Silver Lake (Harald Reinl, 1962).

German postcard, no. E 76. Photo: Constantin.

Götz George and

Karin Dor in

Der Schatz im Silbersee / The Treasure of Silver Lake (Harald Reinl, 1962).

German postcard, no. E 77. Photo: Constantin.

Herbert Lom as the bad colonel Cornel in

Der Schatz im Silbersee (Harald Reinl, 1962). In the photo, he has found the treasure of the film title. He and his four mates have found it in the cave of the Silver Lake and have overpowered the old and blind Indian guard.

German postcard, no. E 80. Photo: Constantin.

Karin Dor and

Jan Sid in

Der Schatz im Silbersee / The Treasure of Silver Lake (Harald Reinl, 1962).

The great adventure novels

Karl May’s works are often not considered literature, but rather popular fiction (German: Trivialliteratur). His works is divided in four catagories: the Travel novels, the Youth stories like 'Die Helden des Westens' or 'Unter Geiern' (1987-1988, Among Vultures), the Colportage novels he wrote for Münchmeyer novels, including 'Die Liebe des Ulanen' (1883-1985, The Love of the Ulaan), 'Der verlorne Sohn' (1884–1986, The Prodigal Son), and 'Der Weg zum Glück' (1886–1988, The Road to Happiness), and Other work, like poetry, drama and autobiographical texts.

Karl May's most successful and best-known book is the Youth novel 'Der Schatz im Silbersee' (1890-1891, The Treasure of Silver Lake). May describes the journey of a group of trappers to Silver Lake in the Rocky Mountains and the pursuit of a group of villains led by Cornel Brinkley, also known as ‘Red Cornel’ because of his hair colour. The novel has several simultaneous plot lines that eventually converge and resolve at the eponymous Silver Lake. 'Der Schatz im Silbersee' was first published in 1890–1891 as a serial in the magazine

Der Gute Kamerad and released in book form in 1894. It has been filmed twice: first in 1962 as a live-action film under the original title, with Lex Barker as Old Shatterhand and Pierre Brice as Winnetou, and three decades later as a DEFA puppet animation film entitled

Die Spur führt zum Silbersee / The Trail Leads to Silver Lake (1990). The Swiss composer

Othmar Schoeck adapted 'Der Schatz im Silbersee' for opera.

May's other famous works are his Travel novels. May wrote two large cycles: the American West stories featuring Old Shatterhand and the Apache chief Winnetou, and, less famous, the stories of Kara Ben Nemsi and Hadji Halef Omar in North Africa and the Middle East. The youth stories appeared in the period from 1887 to 1897 in the magazine

Der Gute Kamerad. Most of them are set in the Wild West. Unlike in the travel adventures, Old Shatterhand is not the first-person narrator. With few exceptions, May had not visited the places he described, but he compensated successfully for his lack of direct experience through a combination of creativity, imagination, and documentary sources, including maps, travel accounts and guidebooks, as well as anthropological and linguistic studies. The work of writers such as

James Fenimore Cooper,

Gabriel Ferry and

Friedrich Gerstäcker served as his models.

Among May's most successful novels of the American West is the 'Winnetou' trilogy (1893), which introduced the noble and wise chief of the Apaches, becoming May’s most beloved creation. Winnetou is usually accompanied by his white friend and blood brother, Old Surehand a.k.a. Old Shatterhand, from whose narrative perspective the stories about Winnetou are often written. The 'Old Surehand' trilogy (1894-1897, Old Shatterhand), focuses on May’s alter ego in the Wild West.

Another series of novels was set in the Ottoman Empire. In these, the narrator-protagonist, Kara Ben Nemsi, travels with his local guide and servant Hadschi Halef Omar through the Sahara Desert to the Near East, experiencing many exciting adventures. This series includes 'Durch die Wüste' (1892, Through the Desert), the opening volume of the Oriental cycle, 'Im Reiche des silbernen Löwen' (1898, In the Realm of the Silver Lion), continuing Kara Ben Nemsi’s travels in the Middle East, and 'Ardistan und Dschinnistan' (1909, Ardistan and Dschinnistan), a later, more philosophical work reflecting May’s spiritual concerns. These books sold in the millions and were translated into numerous languages, securing

Karl May’s status as a cornerstone of German popular literature.

German postcard, no. E 23. Photo: Constantin.

Lex Barker in

Winnetou I (Harald Reinl, 1963). Caption: "Old Shatterhand has also been sentenced to die at the stake. He regrets emphatically that he rescued Winnetou from the Kiowas. An ordeal by battle will decide."

German postcard, no. E 31. Photo: Constantin.

Mario Adorf (left) as Santer in

Winnetou - 1. Teil / Apache Gold (1963). Caption: "Santer and his gang are still looking for the Apache gold. Unnoticed, they follow the course of the Indians to the hiding place of the treasure."

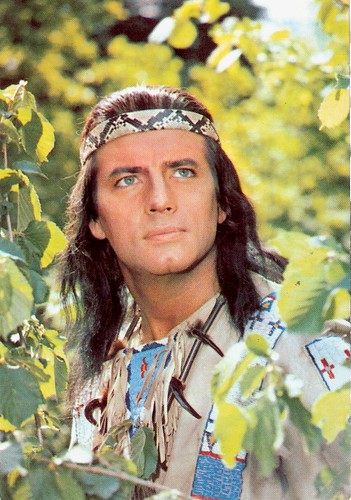

German postcard by ISV, no. R 14.

Pierre Brice in

Winnetou II. Teil / Last of the Renegades (1964).

German postcard, no. R 21.

Klaus Kinski in

Winnetou - 2. Teil / Last of the Renegades (Harald Reinl, 1964). Caption: "With the help of band member Luke, the criminals find the cave and take possession of the women and children of the Assiniboin."

German postcard, no. R 24.

Karin Dor as Ribanna and

Pierre Brice as Winnetou in

Winnetou II. Teil / Last of the Renegades (Harald Reinl, 1964). Caption: "Winnetou is waiting for the Assiniboins and learns to know and love Ribanna."

Karl May and the cinema

Karl May’s visual storytelling and clear-cut heroes made his novels an ideal source material for film. In 1920, May's friends

Marie Luise Droop and

Adolf Droop founded the production company ‘Ustad-Film’ (Ustad = Karl May) in cooperation with Karl May Verlag. They produced three silent films based on the Orient cycle,

Auf den Trümmern des Paradieses / On the Brink of Paradise (Josef Stein, 1920) with

Carl de Vogt as Kara Ben Nemsi, the sequel

Die Todeskarawane / Caravan of Death (Josef Stein, 1920) with

Béla Lugosi in a supporting role as a sheikh, and

Die Teufelsanbeter / The Devil Worshippers (Muhsin Ertuğrul, 1920). The now-lost films had no success, and the company went bankrupt the following year.

In 1936, the first sound film,

Durch die Wüste / Through the Desert (Ferenc Szécsényi, 1936), was released, again based on the Orient cycle. Two decades later, it was followed by the first colour films,

Die Sklavenkarawane / The Slave Caravan (Georg Marischka, Ramón Torrado, 1958) and its sequel

Der Löwe von Babylon / The Lion of Babylon (Johannes Kai, Ramón Torrado, 1959).

Karl May's true cinematic renaissance came in the 1960s, when West German producers launched a highly successful series of colour adventure films. Most of these 18 films are set in the Wild West, beginning with

Der Schatz im Silbersee / The Treasure of the Silver Lake (Harald Reinl, 1962). The majority were produced by

Horst Wendlandt or

Artur Brauner. The film music by Martin Böttcher and the landscapes of Yugoslavia, where most of the films were shot, played a major role in the success of the cinema series.

Key adaptations include

Winnetou – 1. Teil / Winnetou: Part One (Harald Reinl, 1963) and

Old Shatterhand / Old Shatterhand (Hugo Fregonese, 1964). The Karl May films combined sweeping landscapes, memorable music and a romantic vision of adventure. They became iconic across Europe. Recurring leading actors were

Lex Barker (Old Shatterhand, Kara Ben Nemsi, Karl Sternau),

Pierre Brice (Winnetou),

Stewart Granger (Old Surehand), and

Ralf Wolter (Sam Hawkens, Hadschi Halef Omar, André Hasenpfeffer). They cemented May’s characters as screen legends and influenced the look and feel of European Westerns and adventure cinema.

In the following decades, further films were made for the cinema, like the East German animation film

Die Spur führt zum Silbersee (1990) and television, including

Das Buschgespenst (1986) and Winnetou – Der Mythos lebt (2016), as well as TV series such as

Kara Ben Nemsi Effendi (1973-1975). However, most of the films have almost nothing in common with the original books. In 2001,

Michael Herbig, alias ‘Bully’, released the film

Der Schuh des Manitu / Manitou's Shoe (Michael Herbig, 2001), which became one of the most successful German films since the Second World War. It parodies not so much the books as the film adaptations starring

Pierre Brice and

Lex Barker and is based on a similar parody in his comedy show

Bullyparade.

German postcard by Heinerle Karl-May-Postkarten, no. 15. Photo: CCC / Gloria.

Lex Barker and

Ralf Wolter in

Der Schut / The Yellow One (Robert Siodmak, 1964). Caption: "In the evening at house Galingré: "Halef, I will play a trick on the Mübarek. Therefore, you had to get me bismuth and mercury. From this, I'll make bullets that look like lead bullets, but disintegrate during firing. Now I'll load the gun alternately with a bullet made of lead and a fake one ..."

West German postcard by Heinerle Karl-May-Postkarten, no. 25. Photo: CCC / Gloria-Verleih.

Pierre Fromont and

Marie Versini in

Der Schut / The Yellow One (Robert Siodmak, 1964). Caption: "Monsieur Galingré - for God's sake, what are you doing!" - "Don't mind me! Get out of here as fast as you can, or you'll be lost!" - "You'll pay for this, Frenchman, you scoundrel!"

German postcard by Heinerle Karl-May-Postkarten, no. 37. Photo: CCC / Gloria.

Lex Barker and

Marianne Hold in

Der Schut / The Yellow One (Robert Siodmak, 1964). Caption: "A short break is inserted, so Madame Galingré can recover from the rigours of the raid. The next morning, the search for the Yellow One will be continued."

German postcard by Heinerle Karl-May-Postkarten, no. 39. Photo: CCC / Gloria.

Dusan Janicijevic,

Lex Barker and

Ralf Wolter in

Der Schut / The Yellow One (Robert Siodmak, 1964). Caption: "They have pulled Halef into the canyon lodge and tied him up there. 'Where is Kara holding on? Speak... or! '- But Halef remains silent and resists all threats and beatings."

German postcard by Heinerle Karl-May-Postkarten, no. 48. Photo: CCC / Gloria.

Lex Barker and

Ralf Wolter in

Der Schut / The Yellow One (Robert Siodmak, 1964). Caption: "The Farewell Bell Tolls. Kara wants to return to his homeland. Sad Halef says his beloved Lord, "Good-bye". "Sidi, we 'll meet again, when the son of Rih has seen the light of day!"

A uniquely European dream of faraway worlds

Karl May died in 1912 in his own Villa Shatterhand in Radebeul, near Dresden. May was buried in Radebeul East. His tomb was inspired by the Temple of Athena Nike. "A thief, an impostor, a sexual pervert, a grotesque prophet of a sham Messiah!"..."The Third Reich is Karl May's ultimate triumph!" wrote

Klaus Mann, son of

Thomas Mann, in 1940. To which

Albert Einstein replied: "...even today he has been dear to me in many a desperate hour."

Herman Hesse called his books "indispensable and eternal", and the director Carl Zuckmayer even christened his daughter Winnetou in honour of May's great Apache chief. May was very conscious of distancing himself from the ethnological prejudices of his time, but May was not unaffected by the nationalism and racism that characterised Wilhelmine Germany at the time. May's most famous character, Winnetou, chief of the Mescalero Apaches, embodies the brave and noble Indian who fights for justice and peace with his ‘silver rifle’ and his horse Iltschi. Today, May's work is read with a more critical awareness of its stereotypes, yet his importance to popular culture remains undeniable.

Since 1987, a 120-volume historical-critical edition of

Karl May's works has been published. This philologically reliable edition endeavours to reproduce the authentic wording of the first editions and, where possible, also of the author's manuscripts, and provides information on the text's history. It was accompanied by efforts by Karl May Verlag to use legal means to hinder its competitors and prohibit them from criticising the collected works of KMV. After years of disputes and several changes of publisher, the historical-critical edition has been published by Karl May Verlag since 2008, with the Karl May Society responsible for the text and the Karl May Foundation with the Karl May Museum responsible for distribution.

Karl May has been one of the world's most widely read authors for more than 100 years. His work has been translated into 46 languages. The worldwide circulation of his works, set in the Middle East, the United States and 19th-century Mexico, is estimated at 200 million, 100 million of which are in Germany. His books are still very popular today, especially in Czechia, Hungary, Bulgaria, the Netherlands, Mexico and even Indonesia, but he is almost unknown in France, Great Britain and the United States. May's life has been the subject of several films, including

Freispruch für Old Shatterhand (Hans Heinrich, 1965),

Karl May (Hans-Jürgen Syberberg, 1974) and the TV series

Karl May (Klaus Überall, 1992).

The first stage adaptation, 'Winnetou', was created in 1919 by

Hermann Dimmler. Various adaptations of the novels are also performed on open-air stages. The oldest productions have been staged since 1938 at the Felsenbühne Rathen in Saxon Switzerland. The best known are the annual Karl May Festival in Bad Segeberg (since 1952) and the Karl May Festival in Elspe (since 1958). The Karl May Festival in Bischofswerda, which has been running since 1993, offers something special, with children playing the characters. In 2006 alone, plays based on Karl May's works were performed on 14 stages. The first card games, especially various quartet games, appeared around 1935. The Karl May film wave of the 1960s brought a particular boom for the latter. The first puzzles also appeared around 1965.

From 1930 onwards, motifs from Karl May's works and stage and film adaptations were used for collectable pictures. The first two waves took place in the 1930s and the post-war period. At that time, the pictures were mainly used to promote customer loyalty for margarine, cheese, cigarettes, chewing gum, tea and other products from various manufacturers. The third wave came in the wake of the Karl May film adaptations of the 1960s, when collectable albums related to the films were published. In addition to photos from the films, drawings and images from the

Karl May plays in Rathen (colourised) and Bad Segeberg, as well as from the TV series

Mein Freund Winnetou, were also used. Over 90 collectable picture series have been published. Through his books, the films, the stage adaptations, radio plays, comics and postcards,

Karl May continues to embody a uniquely European dream of faraway worlds – a dream that found one of its most lasting expressions on the cinema screen.

German postcard by ISV, no. C 11. Photo: Constantin.

Stewart Granger and

Götz George in

Unter Geiern / Among Vultures (Alfred Vohrer, 1964).

German postcard by ISV, no. C 13. Photo: Constantin.

Elke Sommer and

Götz George in

Unter Geiern / Among Vultures (Alfred Vohrer, 1964).

German postcard, no. 40. Photo: Constantin.

Pierre Brice and

Gojko Mitic in

Unter Geiern / Among Vultures (Alfred Vohrer, 1964).

German postcard by Krüger. Photo: Bernard of Hollywood / CCC Produktion.

Pierre Brice in

Old Shatterhand (1964). Sent by mail in Luxembourg in 1966.

German postcard, no. 8 (1-56). Photo: CCC Produktion / Constantin.

Guy Madison in

Old Shatterhand (Hugo Fregonese, 1964). Caption: "Captain Bradley leads a group of settlers who want to go west."

German postcard, no. 8. Photo: Rialto / Constantin.

Ralf Wolter in

Winnetou - 3. Teil / Winnetou: The Last Shot (Harald Reinl, 1965).

German postcard, no. 9 (1-32). Photo: Rialto / Constantin.

Rik Battaglia and

Pierre Brice in

Winnetou - 3. Teil / Winnetou: The Last Shot (Harald Reinl, 1965).

German postcard, no. 8. Photo: Rialto / Constantin.

Mario Girotti (

Terence Hill) in

Der Ölprinz / Rampage at Apache Wells (Harald Philipp, 1965). Caption: "The trek reaches according to appointment to the first stage near the river. The young Forsyth secretly sneaks out of the camp and meets with members of the Finders gang in the blockhouse. Here he receives his instructions, for the Finders gang will, in the discharge of the Oil prince, attack the wagons during the night."

German postcard, no. 9. Photo: CCC / Constantin.

Lex Barker and

Pierre Brice in

Winnetou und Shatterhand in Tal der Toten / The Valley of Death (Harald Reinl, 1968). Caption: "Old Shatterhand and Winnetou devise a battle plan against the Murdock Bandits."

West German postcard, no. 34. Photo: CCC / Constantin.

Pierre Brice,

Clarke Reynolds and

Lex Barker in

Winnetou und Shatterhand im Tal der Toten / Winnetou and Shatterhand in the Valley of Death (Harald Reinl, 1968). Caption: Winnetou, Old Shatterhand and Lieutenant Cummings have happily ended the battle in the Valley of Death.

Sources: Wikipedia (

Dutch,

German and

English) and

IMDb.