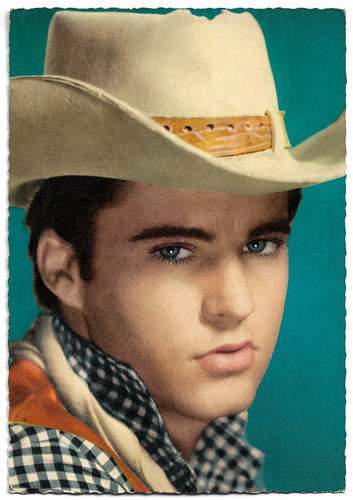

British postcard in the Picturegoer Series, London, no. W 523. Photo: United Artists. Montgomery Clift in Red River (Howard Hawks, 1948).

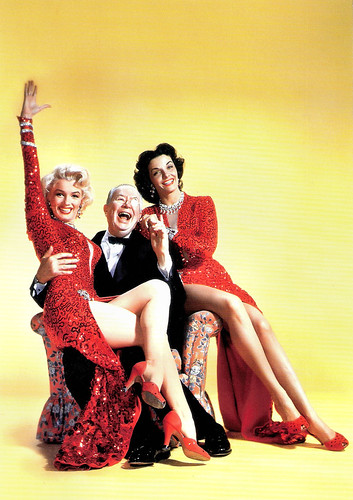

Italian programme card for Il Cinema Ritrovata 2011. Photo: publicity still for Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (Howard Hawks, 1953) with Marilyn Monroe, Charles Coburn and Jane Russell.

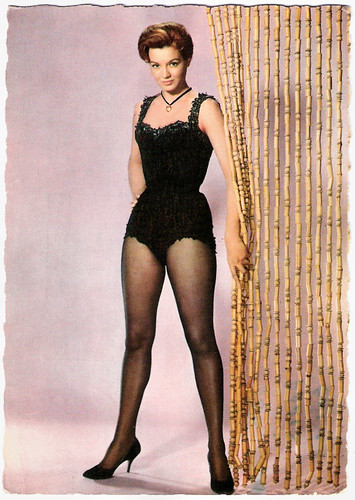

French postcard by E.D.U.G., no. 51. Angie Dickinson in Rio Bravo (Howard Hawks, 1959).

A job as a prop man at Famous Players-Lasky

Howard Hawks' career spanned the freewheeling days of the original independents in the 1910s, through the studio system in Hollywood from the silent era through the talkies, lasting into the early 1970s with the death of the studios and the emergence of the director as auteur, the latter a phenomenon that Hawks himself directly influenced.

He was born Howard Winchester Hawks in Goshen, Indiana, in 1896. He was the first child of Franklin Winchester Hawks and his wife, the former Helen Brown Howard. The day of his birth the local sheriff killed a brawler at the town saloon; the young Hawks was not born on the wild side of town, though, but with the proverbial silver spoon firmly clenched in his young mouth. His wealthy father was a member of Goshen's most prominent family, owner of the Goshen Milling Co. and many other businesses, and his maternal grandfather was one of Wisconsin's leading industrialists.

His father's family had arrived in America in 1630, while his mother's father, C.W. Howard, who was born in Maine in 1845 to parents who emigrated to the U.S. from the Isle of Man, made his fortune in the paper industry with his Howard Paper Co. Ironically, almost a half-year after Howard's birth, the first motion picture was shown in Goshen, just before Christmas on 10 December 1896. Billed as "the scientific wonder of the world," the movie played to a sold-out crowd at the Irwin Theater. However, it disappointed the audience, and attendance fell off at subsequent showings. The interest of the boy raised a Presbyterian would not be piqued again until his family moved to southern California.

The Hawks family relocated from Goshen to Neenah, Wisconsin when Howard's father was appointed secretary/treasurer of the Howard Paper Co. in 1898. Brother Kenneth Hawks was born in 1898 and was looked after by young Howard. However, Howard resented the birth of the family's next son, William B. Hawks, in 1902, and offered to sell him to a family friend for ten cents. A sister, Grace, followed William. Childbirth took a heavy toll on Howard's mother, and she never quite recovered after delivering her fifth child, Helen, in 1906. In order to aid her recovery, the family moved to the more salubrious climate of Pasadena, California, northeast of Los Angeles, for the winter of 1906-1907. The family returned to Wisconsin for the summers, but by 1910 they permanently resettled in California.

Hawks was sent to Philips Exeter Academy in Exeter, New Hampshire, for his education, and upon graduation attended Cornell University, where he majored in mechanical engineering. In both his personal and professional lives Hawks was a risk-taker and enjoyed racing airplanes and automobiles, two sports that he first indulged in his teens with his grandfather's blessing. The Los Angeles area quickly evolved into the centre of the American film industry when studios began relocating their production facilities from the New York City area to southern California in the middle of the 1910s. During one summer vacation, while Howard was matriculating at Cornell, a friend got him a job as a prop man at Famous Players-Lasky (later Paramount Pictures), and he quickly rose through the ranks.

Italian postcard by G.B. Falci, Milano, no. 126. Photo: Fox Film Corp. George O'Brien and Virginia Valli in Paid to Love (Howard Hawks, 1927).

British postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 3917/1, 1928-1929. Photo: Fox. Greta Nissen and Charles Farrell in Fazil (Howard Hawks, 1928).

Dutch postcard for Metropole Palace, Den Haag (The Hague). Photos: 20th Century Fox. Fredric March, June Lang, Warner Baxter, Lionel Barrymore, and Gregory Ratoff in The Road to Glory (Howard Hawks, 1936). Caption: We, 5 stars, are represented in the overwhelming Fox 20th Century millions-film work The Way to Glory. European premiere in the new glorious Metropole Palace, Laan van Meerdervoort, telephone 39.22.44.

British postcard in the A Real Photogravure Portrait series. Photo: James Cagney in Ceiling Zero (Howard Hawks, 1936). Caption: James Cagney managed to support his family as a dancer and singer. This very keen athlete and boxer was discovered on the New York stage by a film scout and sent to Hollywood. His latest pictures are Frisco Kid and Ceiling Zero.

British postcard in the Picturegoer Series, London, no. W 721. Photo: RKO Radio. Danny Kaye in A Song Is Born (Howard Hawks, 1948).

Under the aegis of the eccentric multi-millionaire Howard Hughes

Howard Hawks eventually decided on a career in Hollywood and was employed in a variety of production jobs, including assistant director, casting director, script supervisor, editor and producer. He and his brother Kenneth Hawks shot aerial footage for motion pictures, but Kenneth tragically was killed during a crash while filming. Howard was hired as a screenwriter by Paramount in 1922 and was tasked with writing 40 storylines for new films in 60 days. He bought the rights for works by such established authors as Joseph Conrad and worked, mostly uncredited, on the scripts for approximately 60 films. Hawks wanted to direct, but Paramount refused to indulge his ambition. A Fox executive did, however, and Hawks directed his first film, The Road to Glory (1926), also doubling as the screenwriter.

Hawks made a name for himself by directing eight silent films in the 1920s. Paid to Love (1927) is notable in Hawks' filmography because it was a highly stylised, experimental film. He attempted to imitate the style of German film director F. W. Murnau. Hawks's film includes atypical tracking shots, expressionistic lighting and stylistic film editing that was inspired by German Expressionist cinema. A Girl in Every Port (1928) is the most important film of Hawks' silent career. It is the first of his films to utilize many of the Hawksian themes and characters that would define much of his subsequent work. It was his first "love story between two men", with two men bonding over their duty, skills, and careers, who consider their friendship to be more important than their relationships with women.

His facility for language helped him to thrive with the dawn of talking pictures, and he really established himself with his first talkie in 1930, the classic World War I aviation drama The Dawn Patrol (1930). His arrival as a major director was marked by the controversial and highly popular gangster picture Scarface (1932), a thinly disguised bio of Chicago gangster Al Capone, which was made for producer Howard Hughes. His first great film, it catapulted him into the front rank of directors and remained Hawks' favourite film. Under the aegis of the eccentric multi-millionaire Hughes, it was the only movie he ever made in which he did not have to deal with studio meddling. It leavened its ultra-violence with comedy in a potent brew that has often been imitated by other directors. Though always involved in the development of the scripts of his films, Hawks was lucky to have worked with some of the best writers in the business, including his friend and fellow aviator William Faulkner. Screenwriters he collaborated with on his films included Leigh Brackett, Ben Hecht, John Huston and Billy Wilder.

Hawks often recycled storylines from previous films, such as when he jettisoned the shooting script of El Dorado (1966) during production and reworked the film-in-progress into a remake of Rio Bravo (1959). It was Hawks' directorial skills, his ability to ensure that the audience was not aware of the twice-told nature of his films, through his engendering of high-octane, heady energy that made his films move and made them classics at best and extremely enjoyable entertainments at their "worst." Hawks' genius as a director also manifested itself in the direction of his actors, his moulding of their line readings going a long way toward making his films outstanding. The dialogue in his films often was delivered at a staccato pace, and characters' lines frequently overlapped a Hawks trademark.

Jon C. Hopwood at IMDb: "The spontaneous feeling of his films and the naturalness of the interrelationships between characters were enhanced by his habit of encouraging his actors to improvise. Unlike Alfred Hitchcock, Hawks saw his lead actors as collaborators and encouraged them to be part of the creative process. He had an excellent eye for talent and was responsible for giving the first major breaks to a roster of stars, including Paul Muni, Carole Lombard (his cousin), Lauren Bacall, Montgomery Clift and James Caan. It was Hawks, and not John Ford, who turned John Wayne into a superstar, with Red River (1948). He proceeded to give Wayne some of his best roles in the cavalry trilogy of Fort Apache (1948), She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949) and Rio Grande (1950), in which Wayne played a broad range of diverse characters."

Belgian collectors card by De Beukelaere, Antwerp, no. A 11. Photo: United Artists. John Wayne in Red River (Howard Hawks, 1948).

Dutch postcard, no. 3286. Photo: 20th Century Fox. Cary Grant in I Was a Male War Bride (Howard Hawks, 1949).

British postcard in the Picturegoer series, London, no. D 301. Elizabeth Threatt in The Big Sky (Howard Hawks, 1952). Collection: Marlene Pilaete. Comment: 'Marlene: I’m a bit puzzled by the reference to Republic Pictures on the postcard. Elizabeth Threatt’s only movie was distributed by R.K.O. and I haven’t found any mention of her being under contract to Republic. Maybe it’s a mistake.' We agree that it must be a mistake.

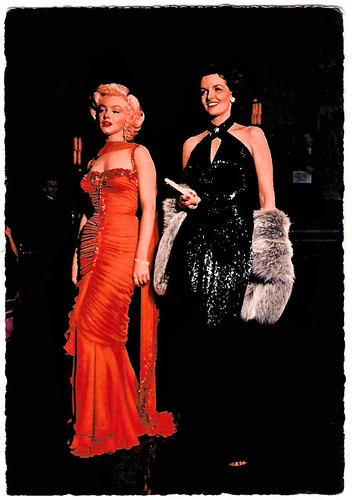

West-German postcard by Krüger, no. 902/14. Photo: Marilyn Monroe and Jane Russell in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (Howard Hawks, 1953).

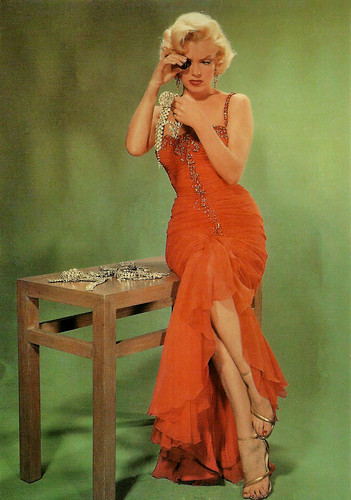

French postcard, no. Réf. Marilyn 97. Marilyn Monroe in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (Howard Hawks, 1953).

Cary Grant in drag

During the 1930s Howard Hawks moved from hit to hit, becoming one of the most respected directors in the business. Jon C. Hopwood: "As his fame waxed, Hawks' image replaced the older, jodhpurs-and-megaphone image of the Hollywood director epitomised by Cecil B. DeMille. The new paradigm of the Hollywood director in the public eye was, like Hawks himself, tall and silver-haired, a Hemingwayesque man of action who was a thorough professional and did not fail his muse or falter in his mastery of the medium while on the job. The image of Hawks as the ultimate Hollywood professional persists to this day in Hollywood, and he continues to be a major influence on many of today's filmmakers."

Hawks was determined to remain independent and refused to attach himself to a studio, or to a particular genre, for an extended period of time. His work ethic allowed him to fit in with the production paradigms of the studio system, and he eventually worked for all eight of the major studios. A Hawks film typically focuses on a tightly bound group of professionals, often isolated from society at large, who must work together as a team if they are to survive, let alone triumph. His movies emphasize such traits as loyalty and self-respect. Air Force (1943), one of the finest propaganda films to emerge from World War II, is such a picture, in which a unit bonds aboard a B-17 bomber and the group is more than the sum of the individuals. Hawks' main theme is Hemingwayesque: the execution of one's job or duty to the best of one's ability in the face of overwhelming odds that would make an average person balk. The main characters in a Hawks film typically are people who take their jobs with the utmost seriousness, as their self-respect is rooted in their work.

In a sense, Hawks' oeuvre can be boiled down to two categories: action-adventure films and comedies. In his action-adventure movies, such as Only Angels Have Wings (1939), the male protagonist, played by Cary Grant, one of Hawks' favourite actors, is both a hero and the top dog in his social group. In the comedies, such as Bringing Up Baby (1938), Cary Grant is no hero but rather a victim of women and society. Women have only a tangential role in Hawks' action films, whereas they are the dominant figures in his comedies. Men are constantly humiliated in comedies, or are subject to role reversals like the man as the romantically hunted prey in "Baby," or the even more dramatic role reversal, including Cary Grant in drag, in I Was a Male War Bride (1949). In action-adventure films in which women are marginalized, they are forced to undergo elaborate courting rituals to attract their men, who they cannot get until they prove themselves as tough as men. There is an undercurrent of homo-eroticism to the Hawk's action films, and Hawks himself termed his A Girl in Every Port (1928) "a love story between two men." This homo-erotic leitmotif is most prominent in Red River (1948).

Hawks' films not only span a wide variety of genres but frequently rank with the best in those genres, whether the war film (The Dawn Patrol (1930)), the gangster film (Scarface ()), the Screwball comedy (His Girl Friday (1940)), the action-adventure film (Only Angels Have Wings (1939)), the Film Noir (The Big Sleep (1946)), the Western (Red River (1948) and Rio Bravo (1959)), the musical-comedy (Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953)) and the historical epic (Land of the Pharaohs (1955)). He even had a hand in creating one of the classic science-fiction films, The Thing from Another World (1951), which was produced by Hawks but directed by Christian Nyby, who had edited multiple Hawks films and who, in his sole directorial effort, essentially created a Hawks film.

Though Howard Hawks created some of the most memorable moments in the history of American film a half-century ago, serious critics generally eschewed his work, as they did not believe there was a controlling intelligence behind them. Seen as the consummate professional director in the industrial process that was the studio film, serious critics believed that the great moments of Hawks' films were simply accidents that accrued from working in Hollywood with other professionals. In his 1948 book 'The Film Till Now," Richard Griffin summed this feeling up with "Hawks is a very good all-rounder." Serious critics at the time attributed the mantle of "artist" to a director only when they could discern artistic aspirations, a personal visual style, or serious thematic intent. Hawks seemed to them an unambitious, commercial Hollywood director who was good enough to turn out first-rate entertainment in a wide variety of genre films in a time in which genre films such as the melodrama, the war picture and the gangster picture were treated with a lack of respect. The critical perception of Hawks began to change when the auteur theory - the idea that one intelligence was responsible for the creation of superior films regardless of their designation as "commercial" or "art house" - began to influence American film criticism. Commenting on Hawks' facility to make films in a wide variety of genres, critic Andrew Sarris, who introduced the auteur theory to American film criticism, said of Hawks, "For a major director, there are no minor genres." A Hawks genre picture is rooted in the conventions and audience expectations typical of the Hollywood genre. The Hawks genre picture does not radically challenge, undermine or overthrow either the conventions of the genre or the audience expectations of the genre film, but expands it the genre by revivifying it with new energy.

West-German postcard by ISV, no. H 65. Ricky Nelson in Rio Bravo (Howard Hawks, 1959).

Italian postcard by Rotalcolor, Milano, no. N. 178. Photo: Warner Bros. Elsa Martinelli in Hatari! (Howard Hawks, 1962).

Romanian postcard by Casa Filmului Acin, no. 103. Photo: Elsa Martinelli in Hatari! (Howard Hawks, 1962).

Romanian postcard by Casa Filmului Acin, no. 212. James Caan in El Dorado (Howard Hawks, 1967).

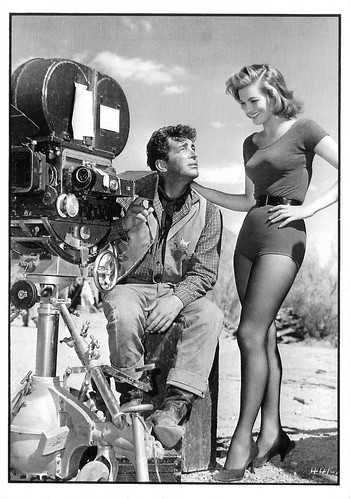

French postcard in the Entr'acte series by Éditions Asphodèle. Mâcon, no. 006/7. Collection: B. Courtel / D.R. Dean Martin and Angie Dickinson in 1958 at the set of Rio Bravo (Howard Hawks, 1959). Caption: Dean Martin and his partner Angie Dickinson behind the camera for a break.

Sources: Jon C. Hopwood (IMDb), Wikipedia and IMDb.

No comments:

Post a Comment