Dutch cinema historian Karel Dibbets died earlier this week. He was a scholar at the University of Amsterdam, co-published De Nederlandse film en bioscoop tot 1940 - a history of Dutch cinema to 1940, co-edited the volume Film and the First World War, and was the founding father of Cinema Context, an extensive online interactive encyclopedia of film culture in the Netherlands from 1896 to the present. He was also a friend of my partner, Ivo Blom, and me. Ivo wrote a tribute to Karel on his personal site: In memoriam: Karel Dibbets (1947-2017). For EFSP, I chose for a post on Karel's 1993 Dutch-written academic thesis, Sprekende films (Talking Pictures), about the introduction of sound film in the Netherlands between 1928 and 1933. It's one of the best film history books ever published in the Netherlands: a sometimes hilarious and exciting read, thoroughly researched and very well written.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 3375/1, 1928-1929. Photo: United Artists. Publicity still for Two Lovers (Fred Niblo, 1928) with Vilma Banky and Ronald Colman. On 22 January 1929, scenes with sound of the American film Two Lovers were shown to the Dutch press. The press was invited for the demonstration by innovative cinema entrepreneur Loet C. Barnstijn in his showroom in The Hague. The programme, including short films and scenes from another early sound film, Tempest (Sam Taylor, 1928), were presented with his 'Loetafoon'. On behalf of Barnstijn, Philips, under the direction of The Hague engineer Frits Prinsen, had developed this system to mix sound with film. The system worked with gramophone records.

French postcard by Europe, no. 452. Photo: United Artists / Regal Film. Publicity still for The Iron Mask (Allan Dwan, 1929) with Douglas Fairbanks. The Iron Mask was shown in Dutch cinemas as a sound film without dialogues. The United Artists production was a box office hit in the Dutch cinemas.

French postcard by Cinémagazine Edition, Paris, no. 794. Photo: Paramount. Publicity still for The Love Parade (Ernst Lubitsch, 1929) with Maurice Chevalier and Jeanette MacDonald. American musicals became all the rage in Dutch cinemas in 1929. They bridged the language barrier. One of the best examples was The Love Parade (1929).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 5108/2, 1930-1931. Photo: MGM. Publicity still for Anna Christie (Clarence Brown, 1930) with Greta Garbo. Around 1930, there were no subtitles and Dutch audiences understood German dialogues better than English. So when Garbo spoke for the first time on screen in Anna Christie, Dutch audiences heard her famous first line in German: "Whisky – aber nicht zu knapp!

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 4451/1, 1929-1930. Photo: Atelier Schlosser & Wenisch, Prague. The British thriller Blackmail (Alfred Hitchcock, 1929), starring Anny Ondra, was shown in a German language version in The Netherlands. After starting production as a silent film, producer British International Pictures decided to convert Blackmail into a sound film during filming, becoming the first successful European dramatic talkie; a silent version was released for theatres not equipped for sound, with the sound version released at the same time.

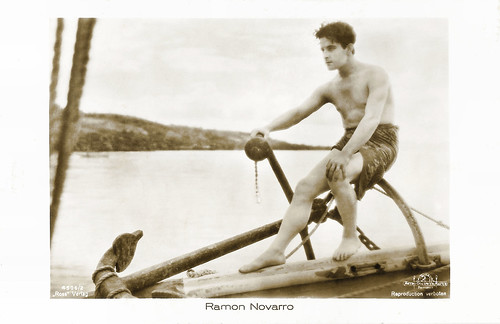

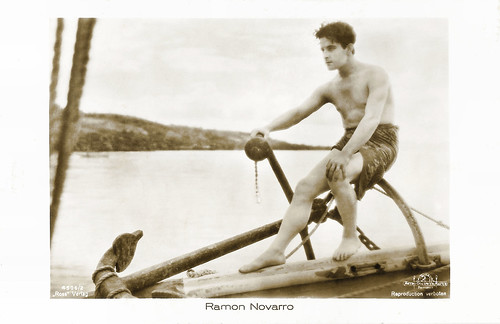

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 4907/3/4, 1929-1930. Photo: MGM. Publicity still for The Pagan (W.S. Van Dyke, 1929) with Ramon Novarro. Another genre that became popular after the introduction of sound was the exotic films as made by W.S. Van Dyke. His films tell about paradise areas where mysterious singing sounds... His The Pagan is a silent/part talking romantic drama filmed in Tahiti. Novarro made a successful transition to sound cinema by singing the Pagan Love Song in this film.

Austrian postcard by Iris-Verlag, no. 6305. Photo: Verleih W. Luschinsky. Europe developed several early sound systems for the cinema. A curious sound system was the Eidophon, developed to produce Catholic films. The first and last Eidophon production was the German melodrama Das Meer ruft/The Sea Calls (Hans Hinrich, 1933), starring Heinrich George. On 26 January 1933, the film had its Dutch premiere at the Tuschinski Theater in Amsterdam with a bishop and an archbishop in the audience.

The transition from silent to sound film started in America. The major breakthrough for the sound technology happened in the 1927-1928 season with the immense success of The Jazz Singer (Alan Crosland, 1927) with Al Jolson in blackface doing Mammy and Mother Of Mine, and singing Toot, Toot, Toosie Goodbye.

In the next seasons, immense problems followed when Hollywood tried to export the new sound film to Europe. The Americans would encounter two serious obstacles in Europe: strange languages and competition. Current techniques like sync and subtitle did not exist yet.

Karel Dibbets describes in Sprekende films the power struggle between the enormous electronics groups of America and Europe about the sound systems. The possession of patents in this new area was the main subject of the controversy.

No other country in Europe so excessively reacted to the arrival of the sound film as the Netherlands. Many air castles were built by entrepreneurs and the fiasco's were as immense. In his book, Dibbets describes how the Netherlands played a central role as the financier of the European sound film.

In 1929 people speculated on the Amsterdam stock exchange with millions, hoping for a good end of this grand film adventure. Well known celebrities such as industrialist Anton Philips, Mr. Brenninkmeyer of the C&A stores, former prime minister Charles Ruijs de Beerenbrouck and author and film activist Menno ter Braak were all intensely involved in the introduction of the sound film.

The advent of the sound film led to the tragic demise of the cinema musicians as a professional group, but it also caused a new wave of Dutch films in the thirties.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 3186/1, 1928-1929. Adolphe Engers was the first Dutch actor who spoke on film. He could be seen and heard in a short film presented on 1 May 1928 at the ITT, an international film exhibition in The Hague. It was the first time the Meisterston sound system, a sound system invented by H.J. Küchenmeister, was demonstrated for the public. In 1932, Adolphe Engers was also the first actor who spoke in a feature film. In Terra nova (Gerard Rutten, 1932), played a fisherman who shouts eagerly awaited news to the people in his village: "De dijk is dicht!" (The dike is closed!). Terra nova tells about the closure of the Zuiderzee, a shallow bay of the North Sea in the northwest of the Netherlands. Terra nova thus connects the start of the sound film with the historic moment when the majority of the Zuiderzee was closed off from the North Sea by the construction of the Afsluitdijk. The film could have been the first Dutch sound feature, but it only got a press show on 1 December 1932. The director and producer quarreled about the final result, after which the film was considered to be lost for unclear reasons. In 1991, the film resurfaced in the Nederlands Filmmuseum (EYE) and was reconstructed and presented again.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 803, 1925-1926. Collection: Marlene Pilaete. Between 1929 and 1931, simultaneous productions in different languages were seen as the solution for the language problems in the international cinemas. On the same set and with the same camera different films were produced. Atlantic (E.A. Dupont, 1929) was the first simultaneous production, made in English, German and French. Paramount op Parade (Job Weening, 1930), filmed at the European Paramount studios in Saint-Maurice, France, was a Dutch language version of Paramount on Parade (Dorothy Arzner, Ernst Lubitsch, a.o., 1930) and featured a sing and dance number by the great Dutch revue star Louis Davids.

Dutch postcard for the Dutch early sound film De Sensatie der toekomst/Television (Dimitri Buchowetzki, Jack Salvatori, 1931) with Lien Deijers, Roland Varno and Dolly Bouwmeester. De Sensatie der toekomst was also produced at the French Paramount studios in Saint-Maurice. It was one of the many alternative language versions of the French film Magie moderne (Dimitri Buchowetzki, 1931) about the new medium television. The film is now considered lost.

Vintage postcard, no. 988/1. Collection: Geoffrey Donaldson Institute. Actor and director Ernst Winar made some early sound shorts in 1932 and 1933, which could be played with a gramophone. These included Een huisje op de hei/A cottage on the heath, accompanying a song by cabaret artist Louis Noiret. These films were made for projection at home by Cinetone, which produced amateur sound projectors.

Dutch postcard by JosPe. Sent by mail in 1935. Photo: Godfried de Groot. In the short film Hollandsch Hollywood (Ernst Winar, 1933), stage actress Fien de la Mar sang the title song about a new Dutch sound film industry. The song proved to be prophetic: in the next years there was a bubble with dozens of Dutch films, and Fien de la Mar became the Dutch film diva.

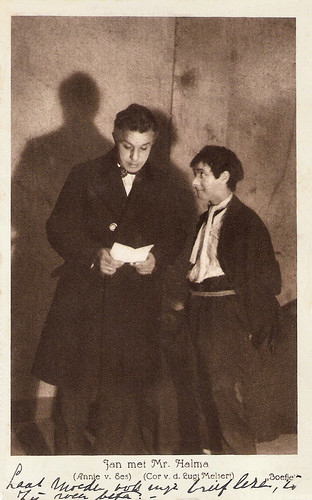

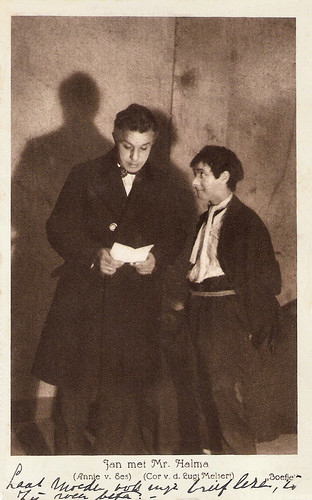

Dutch postcard by N.V. Vereenigd Rotterdamsch Hofstadtoneel, Rotterdam. Photo: Willem Coret. Still for the stage version of Boefje with Cor van der Lugt Melsert and Annie van Ees. Cor van der Lugt Melsert played the lead role in the first Dutch sound feature, the historical drama Willem van Oranje/William of Orange (1934), produced, co-written, and directed by Jan Teunissen. The film portrays the life of William the Silent, 400 years after his birth, and the origins of the Dutch Revolt. The film was produced in Eindhoven in the 'Philiwood' studios. The costume drama was not a success.

Dutch postcard by Hollandia Film Prod. / Loet C. Barnstijn. Photo: publicity still for De Jantjes/The Tars (Jaap Speyer, 1934) with Jan van Ees, Willy Costello and Johan Kaart jr. A huge success was the second Dutch sound film, the musical comedy De Jantjes/The Tars (Jaap Speyer, 1934). It lead to a wave of Dutch films, which was also stimulated by the invention of the sound film.

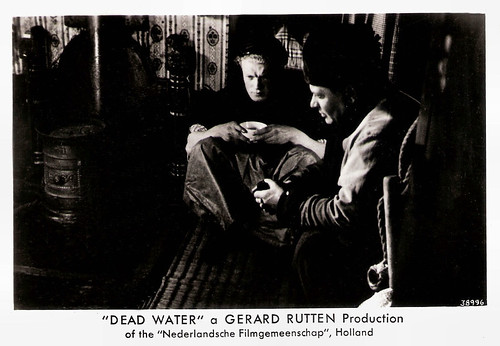

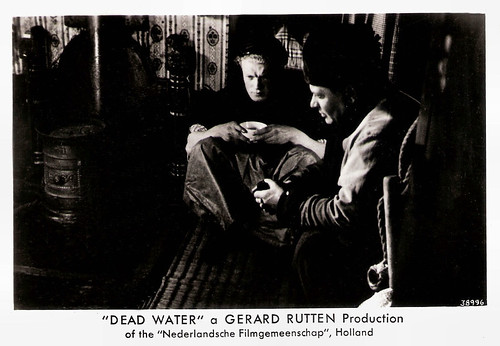

Dutch postcard, no. 38996. Photo: Nederlandse Filmgemeenschap, Holland. Publicity still for Dood water/Dead water (Gerard Rutten, 1934) with Max Croiset and Arnold Marlé. Collection: Egbert Barten. Although his Terra nova did not reach the cinemas, director Gerard Rutten got his breakthrough with another film drama on fishermen and the closing of the Zuiderzee. Dood water/Dead water won an award at the 1934 Venice Film Festival. So, the dike was definitively closed and the Dutch sound film was here to stay.

Source: Karel Dibbets (Sprekende films - Dutch).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 3375/1, 1928-1929. Photo: United Artists. Publicity still for Two Lovers (Fred Niblo, 1928) with Vilma Banky and Ronald Colman. On 22 January 1929, scenes with sound of the American film Two Lovers were shown to the Dutch press. The press was invited for the demonstration by innovative cinema entrepreneur Loet C. Barnstijn in his showroom in The Hague. The programme, including short films and scenes from another early sound film, Tempest (Sam Taylor, 1928), were presented with his 'Loetafoon'. On behalf of Barnstijn, Philips, under the direction of The Hague engineer Frits Prinsen, had developed this system to mix sound with film. The system worked with gramophone records.

French postcard by Europe, no. 452. Photo: United Artists / Regal Film. Publicity still for The Iron Mask (Allan Dwan, 1929) with Douglas Fairbanks. The Iron Mask was shown in Dutch cinemas as a sound film without dialogues. The United Artists production was a box office hit in the Dutch cinemas.

French postcard by Cinémagazine Edition, Paris, no. 794. Photo: Paramount. Publicity still for The Love Parade (Ernst Lubitsch, 1929) with Maurice Chevalier and Jeanette MacDonald. American musicals became all the rage in Dutch cinemas in 1929. They bridged the language barrier. One of the best examples was The Love Parade (1929).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 5108/2, 1930-1931. Photo: MGM. Publicity still for Anna Christie (Clarence Brown, 1930) with Greta Garbo. Around 1930, there were no subtitles and Dutch audiences understood German dialogues better than English. So when Garbo spoke for the first time on screen in Anna Christie, Dutch audiences heard her famous first line in German: "Whisky – aber nicht zu knapp!

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 4451/1, 1929-1930. Photo: Atelier Schlosser & Wenisch, Prague. The British thriller Blackmail (Alfred Hitchcock, 1929), starring Anny Ondra, was shown in a German language version in The Netherlands. After starting production as a silent film, producer British International Pictures decided to convert Blackmail into a sound film during filming, becoming the first successful European dramatic talkie; a silent version was released for theatres not equipped for sound, with the sound version released at the same time.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 4907/3/4, 1929-1930. Photo: MGM. Publicity still for The Pagan (W.S. Van Dyke, 1929) with Ramon Novarro. Another genre that became popular after the introduction of sound was the exotic films as made by W.S. Van Dyke. His films tell about paradise areas where mysterious singing sounds... His The Pagan is a silent/part talking romantic drama filmed in Tahiti. Novarro made a successful transition to sound cinema by singing the Pagan Love Song in this film.

Austrian postcard by Iris-Verlag, no. 6305. Photo: Verleih W. Luschinsky. Europe developed several early sound systems for the cinema. A curious sound system was the Eidophon, developed to produce Catholic films. The first and last Eidophon production was the German melodrama Das Meer ruft/The Sea Calls (Hans Hinrich, 1933), starring Heinrich George. On 26 January 1933, the film had its Dutch premiere at the Tuschinski Theater in Amsterdam with a bishop and an archbishop in the audience.

Talking Pictures in the Netherlands

The transition from silent to sound film started in America. The major breakthrough for the sound technology happened in the 1927-1928 season with the immense success of The Jazz Singer (Alan Crosland, 1927) with Al Jolson in blackface doing Mammy and Mother Of Mine, and singing Toot, Toot, Toosie Goodbye.

In the next seasons, immense problems followed when Hollywood tried to export the new sound film to Europe. The Americans would encounter two serious obstacles in Europe: strange languages and competition. Current techniques like sync and subtitle did not exist yet.

Karel Dibbets describes in Sprekende films the power struggle between the enormous electronics groups of America and Europe about the sound systems. The possession of patents in this new area was the main subject of the controversy.

No other country in Europe so excessively reacted to the arrival of the sound film as the Netherlands. Many air castles were built by entrepreneurs and the fiasco's were as immense. In his book, Dibbets describes how the Netherlands played a central role as the financier of the European sound film.

In 1929 people speculated on the Amsterdam stock exchange with millions, hoping for a good end of this grand film adventure. Well known celebrities such as industrialist Anton Philips, Mr. Brenninkmeyer of the C&A stores, former prime minister Charles Ruijs de Beerenbrouck and author and film activist Menno ter Braak were all intensely involved in the introduction of the sound film.

The advent of the sound film led to the tragic demise of the cinema musicians as a professional group, but it also caused a new wave of Dutch films in the thirties.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 3186/1, 1928-1929. Adolphe Engers was the first Dutch actor who spoke on film. He could be seen and heard in a short film presented on 1 May 1928 at the ITT, an international film exhibition in The Hague. It was the first time the Meisterston sound system, a sound system invented by H.J. Küchenmeister, was demonstrated for the public. In 1932, Adolphe Engers was also the first actor who spoke in a feature film. In Terra nova (Gerard Rutten, 1932), played a fisherman who shouts eagerly awaited news to the people in his village: "De dijk is dicht!" (The dike is closed!). Terra nova tells about the closure of the Zuiderzee, a shallow bay of the North Sea in the northwest of the Netherlands. Terra nova thus connects the start of the sound film with the historic moment when the majority of the Zuiderzee was closed off from the North Sea by the construction of the Afsluitdijk. The film could have been the first Dutch sound feature, but it only got a press show on 1 December 1932. The director and producer quarreled about the final result, after which the film was considered to be lost for unclear reasons. In 1991, the film resurfaced in the Nederlands Filmmuseum (EYE) and was reconstructed and presented again.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 803, 1925-1926. Collection: Marlene Pilaete. Between 1929 and 1931, simultaneous productions in different languages were seen as the solution for the language problems in the international cinemas. On the same set and with the same camera different films were produced. Atlantic (E.A. Dupont, 1929) was the first simultaneous production, made in English, German and French. Paramount op Parade (Job Weening, 1930), filmed at the European Paramount studios in Saint-Maurice, France, was a Dutch language version of Paramount on Parade (Dorothy Arzner, Ernst Lubitsch, a.o., 1930) and featured a sing and dance number by the great Dutch revue star Louis Davids.

Dutch postcard for the Dutch early sound film De Sensatie der toekomst/Television (Dimitri Buchowetzki, Jack Salvatori, 1931) with Lien Deijers, Roland Varno and Dolly Bouwmeester. De Sensatie der toekomst was also produced at the French Paramount studios in Saint-Maurice. It was one of the many alternative language versions of the French film Magie moderne (Dimitri Buchowetzki, 1931) about the new medium television. The film is now considered lost.

Vintage postcard, no. 988/1. Collection: Geoffrey Donaldson Institute. Actor and director Ernst Winar made some early sound shorts in 1932 and 1933, which could be played with a gramophone. These included Een huisje op de hei/A cottage on the heath, accompanying a song by cabaret artist Louis Noiret. These films were made for projection at home by Cinetone, which produced amateur sound projectors.

Dutch postcard by JosPe. Sent by mail in 1935. Photo: Godfried de Groot. In the short film Hollandsch Hollywood (Ernst Winar, 1933), stage actress Fien de la Mar sang the title song about a new Dutch sound film industry. The song proved to be prophetic: in the next years there was a bubble with dozens of Dutch films, and Fien de la Mar became the Dutch film diva.

Dutch postcard by N.V. Vereenigd Rotterdamsch Hofstadtoneel, Rotterdam. Photo: Willem Coret. Still for the stage version of Boefje with Cor van der Lugt Melsert and Annie van Ees. Cor van der Lugt Melsert played the lead role in the first Dutch sound feature, the historical drama Willem van Oranje/William of Orange (1934), produced, co-written, and directed by Jan Teunissen. The film portrays the life of William the Silent, 400 years after his birth, and the origins of the Dutch Revolt. The film was produced in Eindhoven in the 'Philiwood' studios. The costume drama was not a success.

Dutch postcard by Hollandia Film Prod. / Loet C. Barnstijn. Photo: publicity still for De Jantjes/The Tars (Jaap Speyer, 1934) with Jan van Ees, Willy Costello and Johan Kaart jr. A huge success was the second Dutch sound film, the musical comedy De Jantjes/The Tars (Jaap Speyer, 1934). It lead to a wave of Dutch films, which was also stimulated by the invention of the sound film.

Dutch postcard, no. 38996. Photo: Nederlandse Filmgemeenschap, Holland. Publicity still for Dood water/Dead water (Gerard Rutten, 1934) with Max Croiset and Arnold Marlé. Collection: Egbert Barten. Although his Terra nova did not reach the cinemas, director Gerard Rutten got his breakthrough with another film drama on fishermen and the closing of the Zuiderzee. Dood water/Dead water won an award at the 1934 Venice Film Festival. So, the dike was definitively closed and the Dutch sound film was here to stay.

Source: Karel Dibbets (Sprekende films - Dutch).

No comments:

Post a Comment