The effortlessly suave Romanian-born actor Pál Jávor (1902-1959) was one of the first stars of the Hungarian sound cinema. His glamorous and highly successful stage and film career was broken, first by the German invasion of Hungary and again by the Communist government after the war. He moved to Hollywood where he only could play bit parts.

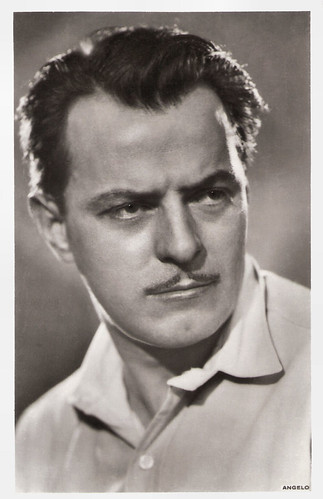

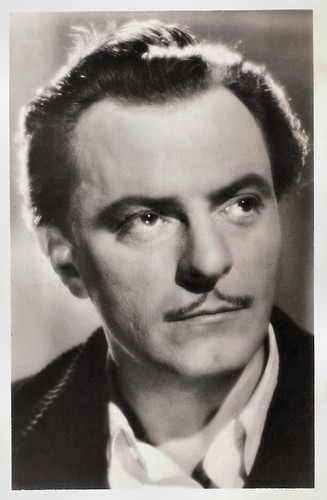

Hungarian postcard by Rakosi Kiado, Budapest, no. 602. Photo: Angelo.

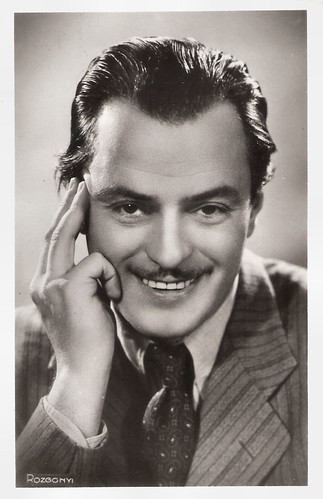

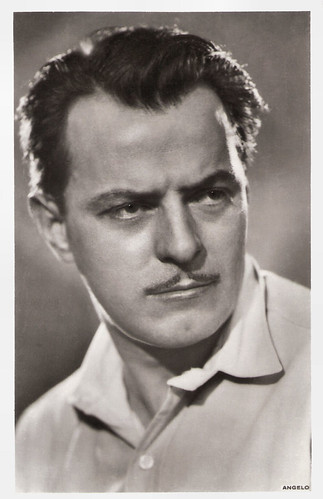

Hungarian postcard by Rakosi Kiado, Budapest, no. 514. Photo: Rozgcnyi.

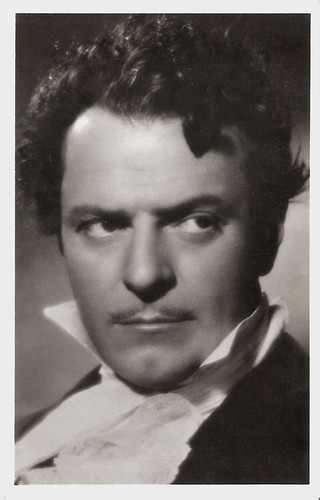

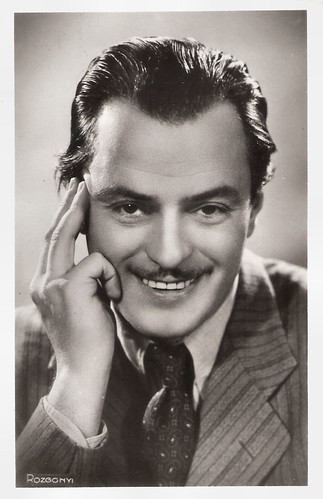

Hungarian postcard by Filmbolt. Photo: Müvelödés Film. Publicity still for Néma kolostor/Silent Monastery (Endre Rodríguez, 1941).

Pál Jávor (sometimes credited as Paul Javor) was born Pál Jermann in Arad, Austria-Hungary (now Romania), in 1902. He was the lovechild of Pál Jermann, a 53-year-old cashier and Katalin Spannenberg, a 17-year-old servant. His parents, who only married after his birth, had 3 children to care for, which made life hard for the family, who often moved.

His mother later opened a grocery store in Arad's Kossuth street. Jávor was a student in a state-operated gymnasium but often played truant to see movies in the town's two theatres. From very early on, he wanted to break away from his homeland, and from the simple life his mother wished for him.

During World War I, he ran away to serve on the front as a courier. He was caught and transported back months later by military police. In 1918, after working as a junior reporter for the Aradi Hírlap, he set out to emigrate to Denmark, so he could act in the Danish films he idolised. As the state offered free train tickets to anyone who wished to leave the country, he willingly chose self-banishment from Romania, but his ticket was revoked in Budapest.

Jávor, now seeking to gain fame in the Hungarian capital, went to study at the Academy of Drama. Living in great poverty, and expelled from the Academy for unknown reasons, he earned his degree in the Actor's Guild school, in 1922. Jávor acted in various theatres in Budapest, Székesfehérvár and several other small towns, but his dissolute lifestyle made him hard to work with.

After being banned from the Guild in 1926, he acted in small roles around the country, and later in Budapest, helped by mentors from the theatrical world, and slowly awakened the interest of the critics. He was a member of the Vígszínház, the Comedy Theatre of Budapest, between 1930–1935, and the National Theatre between 1935-1944.

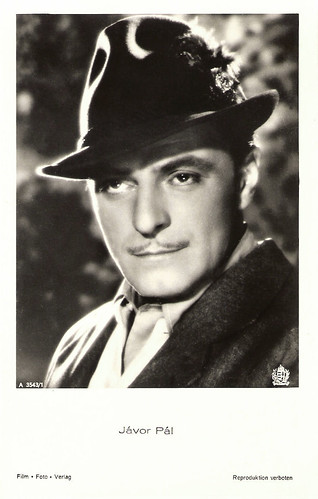

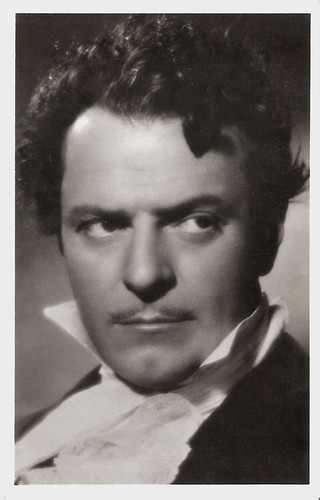

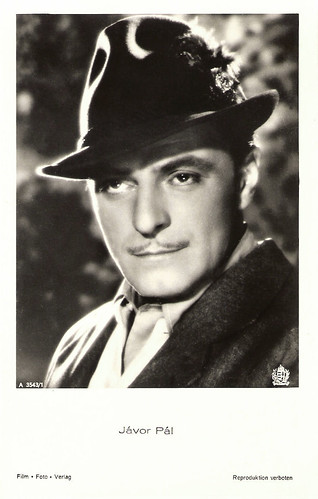

German postcard by Film-Foto-Verlag, no. A 3543/1.

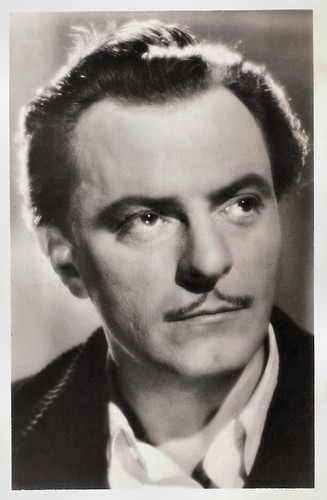

German postcard by Film-Foto-Verlag, no. A 3804/1.

In 1929, Pál Jávor finally got the opportunity to appear in the cinema. He then starred in Csak egy kislány van a világon/The Only Girl in the World (Béla Gaál, 1929) opposite Márta Eggerth, also in her film debut. It was to be the last Hungarian silent film, but, ironically, this was also the first one to feature sound.

The film’s technicians got hold of the technology by the last days of shooting. This allowed Jávor to sing a song in one of the scenes, which, combined with his charm and temperament made him a star of the country's waking film industry. D. Lewis at IMDb: “Despite some slow passages and ellipses in the story caused by missing footage, Csak egy kislány van a világon is an inspired effort with some genuinely great things in it. Director Gaál would go, with considerable success, into comedies in the 1930s, but would end his days, regrettably, in either the Dachau Concentration Camp or at the hands of Nazis on a Budapest street, depending on which account one accepts.”

Jávor took the lead role in the first Hungarian sound film, the comedy Kék Bálvány/A Blue Idol (Lajos Lázár, 1931) with Oscar Beregi Sr. Then followed a smaller part in the second Hungarian sound film, the comedy Hyppolit, a lakáj/Hyppolit, the Butler (István Székely aka Steve Sekely, 1931) starring Gyula Csortos and Gyula Kabos, which became a huge box office hit. Director Istvan Szekeley left Hungary in 1938 to relocate to Hollywood, where he continued to work under the name of Steve Sekely. Hyppolit, a lakáj was shown again in Hungarian cinemas in 1945, 1956 and 1972, and later also returned several times on TV.

After this success, the suave and charming Jávor quickly became an idol of the 1930s, appearing in numerous films, but he also remained popular on stage. However, the sudden fame weighed heavily on the young actor, leading to him returning to alcohol. His frequent clashes with colleagues and journalists resulted in numerous scandals. His life was eased when he met Olga Landesmann, a widow with two children. After their marriage in 1934, she provided him with a home and family. Among his best-known films of that period are the drama Marika (Viktor Gertler, 1938), and the comedy A Noszty fiú esete Tóth Marival/I Married for Love (Steve Sekely (as István Székely), 1938).

There is also a German-language version of the latter, Ihr Leibhusar/Her personal Hussar (Hubert Marischka, 1938), in which he co-stars with Magda Schneider and Paul Kemp. He appeared in more foreign films, including the Austrian-German production Donauschiffer/Danube Boat (Robert A. Stemmle, 1940) with Hilde Krahl, and the Italian Inferno giallo/Yellow Hell (Géza von Radványi, 1942) with Fosco Giachetti.

German postcard by Film-Foto-Verlag, no. A 3817/1, 1941-1944. Photo: Quick.

German postcard by Filmbolt. Photo: Hunnia Film.

After 1940, World War II slowly became part of life for Hungarian citizens and the theatre world alike, working conditions became increasingly harsher, which Pál Jávor could hardly bear. Being anxious about the regulation of the theatre, and the defaming of fellow actors, he often clashed with superiors. Charged with making unlawful political comments, he became the target of the Gestapo. After hiding in Balatonfüred and Agárd, he returned to Budapest, thinking that the danger of arrest was over. After another quarrel with the Actor's Guild's manager, the Guild suspended him from practising the profession and also banned his films. After the German invasion of Hungary, Pál Jávor was arrested by Arrow party members. Jávor was first held in the prison of Sopronkőhida under dire conditions, then transported to Germany.

After being liberated by Allied forces, he awaited the end of the war in Tann and Pfarrkirchen in Austria. His confinement lasted over 9 months, about which he wrote a recollection published in 1946. After the war Jávor found that the theatre world had largely rejected him, offering him only a few roles. The intellectual and cultural cleansing of the new Communist government left him with virtually no possibilities. In, 1946, Jávor made a successful tour of Romania and then travelled to the United States. After arriving in the United States, he was met with great acclaim by the emigrant community, but despite this, he could only arrange small comedic and musical shows, which he found humiliating.

Slowly sinking into depression and reaching again for alcohol, the quality of his shows also sank, emptying audience seats. While he thought about returning home, he received no encouraging news from Hungary, and the increasingly tense political situation also forced him to remain in the States. He travelled to Hollywood to seek film roles, but his lack of English left him few possibilities, like the role of Antonio Scotti in the film The Great Caruso (Richard Thorpe, 1951), starring Mario Lanza. The castings were humiliating and the small roles degrading.

Jávor joined a touring group, performing Hungarian hit songs and oldies. Later he also worked part-time as a gatekeeper and computer operator. During his 11 years in the US, Jávor met numerous difficulties, but he later also remembered joyful moments: he wrote numerous articles in American-Hungarian papers, and with his journalist ID he could visit cinemas for free. Through a voluntary detoxification cure, he gave up his alcohol addiction and befriended several emigrant artists living in America, including Sándor Márai. In 1956, touring Israel with an occasional group, he learnt that he could finally go home. In 1957, he returned to Budapest, awaited by friends, and jobs in the Jókai and Petőfi theatres. However, the years of hardships lay still fresh on Jávor, and several critics found his acting lacking. But his still living legend carried him on, making several successful appearances, and he also was offered a film deal.

But his health could not tolerate the highly intensive life, and after a seizure in 1958, he was transported to a hospital which he never left. While spending over one year in bed, the National Theatre re-hired him, and he was often visited by old friends, also resolving some grudges of the past. But his state worsened, and Pál Jávor died in 1959. He was 57. His burial was a theatrical ceremony and his coffin was followed by tens of thousands of fans to the Farkasréti Cemetery.

Hungarian photo card by HB. Pál Jávor in Dankó Pista (László Kalmár, 1940).

Hungarian postcard by Filmbolt, no. A 102. Photo: Lena Film. Pál Jávor in Szováthy Éva/Eva Szovathy (Ágoston Pacséry, 1943).

Hungarian or German postcard by Agfa.

Sources: D. Lewis (IMDb), Wikipedia and IMDb.

This post was last updated on 18 November 2024.

Hungarian postcard by Rakosi Kiado, Budapest, no. 602. Photo: Angelo.

Hungarian postcard by Rakosi Kiado, Budapest, no. 514. Photo: Rozgcnyi.

Hungarian postcard by Filmbolt. Photo: Müvelödés Film. Publicity still for Néma kolostor/Silent Monastery (Endre Rodríguez, 1941).

Idolising Danish silent films

Pál Jávor (sometimes credited as Paul Javor) was born Pál Jermann in Arad, Austria-Hungary (now Romania), in 1902. He was the lovechild of Pál Jermann, a 53-year-old cashier and Katalin Spannenberg, a 17-year-old servant. His parents, who only married after his birth, had 3 children to care for, which made life hard for the family, who often moved.

His mother later opened a grocery store in Arad's Kossuth street. Jávor was a student in a state-operated gymnasium but often played truant to see movies in the town's two theatres. From very early on, he wanted to break away from his homeland, and from the simple life his mother wished for him.

During World War I, he ran away to serve on the front as a courier. He was caught and transported back months later by military police. In 1918, after working as a junior reporter for the Aradi Hírlap, he set out to emigrate to Denmark, so he could act in the Danish films he idolised. As the state offered free train tickets to anyone who wished to leave the country, he willingly chose self-banishment from Romania, but his ticket was revoked in Budapest.

Jávor, now seeking to gain fame in the Hungarian capital, went to study at the Academy of Drama. Living in great poverty, and expelled from the Academy for unknown reasons, he earned his degree in the Actor's Guild school, in 1922. Jávor acted in various theatres in Budapest, Székesfehérvár and several other small towns, but his dissolute lifestyle made him hard to work with.

After being banned from the Guild in 1926, he acted in small roles around the country, and later in Budapest, helped by mentors from the theatrical world, and slowly awakened the interest of the critics. He was a member of the Vígszínház, the Comedy Theatre of Budapest, between 1930–1935, and the National Theatre between 1935-1944.

German postcard by Film-Foto-Verlag, no. A 3543/1.

German postcard by Film-Foto-Verlag, no. A 3804/1.

Suave and charming

In 1929, Pál Jávor finally got the opportunity to appear in the cinema. He then starred in Csak egy kislány van a világon/The Only Girl in the World (Béla Gaál, 1929) opposite Márta Eggerth, also in her film debut. It was to be the last Hungarian silent film, but, ironically, this was also the first one to feature sound.

The film’s technicians got hold of the technology by the last days of shooting. This allowed Jávor to sing a song in one of the scenes, which, combined with his charm and temperament made him a star of the country's waking film industry. D. Lewis at IMDb: “Despite some slow passages and ellipses in the story caused by missing footage, Csak egy kislány van a világon is an inspired effort with some genuinely great things in it. Director Gaál would go, with considerable success, into comedies in the 1930s, but would end his days, regrettably, in either the Dachau Concentration Camp or at the hands of Nazis on a Budapest street, depending on which account one accepts.”

Jávor took the lead role in the first Hungarian sound film, the comedy Kék Bálvány/A Blue Idol (Lajos Lázár, 1931) with Oscar Beregi Sr. Then followed a smaller part in the second Hungarian sound film, the comedy Hyppolit, a lakáj/Hyppolit, the Butler (István Székely aka Steve Sekely, 1931) starring Gyula Csortos and Gyula Kabos, which became a huge box office hit. Director Istvan Szekeley left Hungary in 1938 to relocate to Hollywood, where he continued to work under the name of Steve Sekely. Hyppolit, a lakáj was shown again in Hungarian cinemas in 1945, 1956 and 1972, and later also returned several times on TV.

After this success, the suave and charming Jávor quickly became an idol of the 1930s, appearing in numerous films, but he also remained popular on stage. However, the sudden fame weighed heavily on the young actor, leading to him returning to alcohol. His frequent clashes with colleagues and journalists resulted in numerous scandals. His life was eased when he met Olga Landesmann, a widow with two children. After their marriage in 1934, she provided him with a home and family. Among his best-known films of that period are the drama Marika (Viktor Gertler, 1938), and the comedy A Noszty fiú esete Tóth Marival/I Married for Love (Steve Sekely (as István Székely), 1938).

There is also a German-language version of the latter, Ihr Leibhusar/Her personal Hussar (Hubert Marischka, 1938), in which he co-stars with Magda Schneider and Paul Kemp. He appeared in more foreign films, including the Austrian-German production Donauschiffer/Danube Boat (Robert A. Stemmle, 1940) with Hilde Krahl, and the Italian Inferno giallo/Yellow Hell (Géza von Radványi, 1942) with Fosco Giachetti.

German postcard by Film-Foto-Verlag, no. A 3817/1, 1941-1944. Photo: Quick.

German postcard by Filmbolt. Photo: Hunnia Film.

Target of the Gestapo

After 1940, World War II slowly became part of life for Hungarian citizens and the theatre world alike, working conditions became increasingly harsher, which Pál Jávor could hardly bear. Being anxious about the regulation of the theatre, and the defaming of fellow actors, he often clashed with superiors. Charged with making unlawful political comments, he became the target of the Gestapo. After hiding in Balatonfüred and Agárd, he returned to Budapest, thinking that the danger of arrest was over. After another quarrel with the Actor's Guild's manager, the Guild suspended him from practising the profession and also banned his films. After the German invasion of Hungary, Pál Jávor was arrested by Arrow party members. Jávor was first held in the prison of Sopronkőhida under dire conditions, then transported to Germany.

After being liberated by Allied forces, he awaited the end of the war in Tann and Pfarrkirchen in Austria. His confinement lasted over 9 months, about which he wrote a recollection published in 1946. After the war Jávor found that the theatre world had largely rejected him, offering him only a few roles. The intellectual and cultural cleansing of the new Communist government left him with virtually no possibilities. In, 1946, Jávor made a successful tour of Romania and then travelled to the United States. After arriving in the United States, he was met with great acclaim by the emigrant community, but despite this, he could only arrange small comedic and musical shows, which he found humiliating.

Slowly sinking into depression and reaching again for alcohol, the quality of his shows also sank, emptying audience seats. While he thought about returning home, he received no encouraging news from Hungary, and the increasingly tense political situation also forced him to remain in the States. He travelled to Hollywood to seek film roles, but his lack of English left him few possibilities, like the role of Antonio Scotti in the film The Great Caruso (Richard Thorpe, 1951), starring Mario Lanza. The castings were humiliating and the small roles degrading.

Jávor joined a touring group, performing Hungarian hit songs and oldies. Later he also worked part-time as a gatekeeper and computer operator. During his 11 years in the US, Jávor met numerous difficulties, but he later also remembered joyful moments: he wrote numerous articles in American-Hungarian papers, and with his journalist ID he could visit cinemas for free. Through a voluntary detoxification cure, he gave up his alcohol addiction and befriended several emigrant artists living in America, including Sándor Márai. In 1956, touring Israel with an occasional group, he learnt that he could finally go home. In 1957, he returned to Budapest, awaited by friends, and jobs in the Jókai and Petőfi theatres. However, the years of hardships lay still fresh on Jávor, and several critics found his acting lacking. But his still living legend carried him on, making several successful appearances, and he also was offered a film deal.

But his health could not tolerate the highly intensive life, and after a seizure in 1958, he was transported to a hospital which he never left. While spending over one year in bed, the National Theatre re-hired him, and he was often visited by old friends, also resolving some grudges of the past. But his state worsened, and Pál Jávor died in 1959. He was 57. His burial was a theatrical ceremony and his coffin was followed by tens of thousands of fans to the Farkasréti Cemetery.

Hungarian photo card by HB. Pál Jávor in Dankó Pista (László Kalmár, 1940).

Hungarian postcard by Filmbolt, no. A 102. Photo: Lena Film. Pál Jávor in Szováthy Éva/Eva Szovathy (Ágoston Pacséry, 1943).

Hungarian or German postcard by Agfa.

Sources: D. Lewis (IMDb), Wikipedia and IMDb.

This post was last updated on 18 November 2024.

1 comment:

My mother and I spent every Sunday enjoying his films at the Europa Theater in New Brunswick, NJ

Post a Comment