We continue a yearly tradition, EFSP follows Il Cinema Ritrovato from 21 - 29 June. We love the festival dedicated to cinematic masterpieces, timeless classics, and hidden gems. For nine days, films will be screened across seven theatres and two open-air venues — Piazza Maggiore and the steamy and carbon-lit Piazzetta Pasolini. Molly Haskell curated 'Katharine Hepburn: Feminist, Acrobat and Lover' for this year's edition. Katharine Hepburn (1907-2003) was a spirited performer with a touch of eccentricity. The actress introduced into her roles a strength of character previously considered to be undesirable in Hollywood leading ladies. She was also noted for her brisk upper-class New England accent and tomboyish beauty. Haskell: "She was bold and 'out there' in a way few women were - exhilarating, physically nimble, androgyne and lady rolled into one. There was a reason her career spanned 67 years and boasted a still-record number of Best Actress Oscar nominations (12) and wins (4). Her career was more varied than she’s given credit for, but it’s especially her screwball comedies (of which there’s a touch in all her best work) that she shines. Unique and irreplaceable, we are able to appreciate in our own time this woman who was so ahead of hers."

French postcard by Viny, no. 31. Photo: R.K.O.

Belgian postcard by N.V. Victoria, Brussels, no. 12. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

British postcard by De Reszke Cigarettes, no. 34. Photo: Radio (RKO).

British postcard. Photo: RKO / Radio Pictures. Katharine Hepburn in Christopher Strong (Dorothy Arzner, 1933).

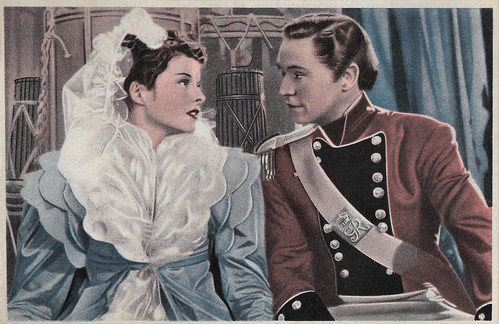

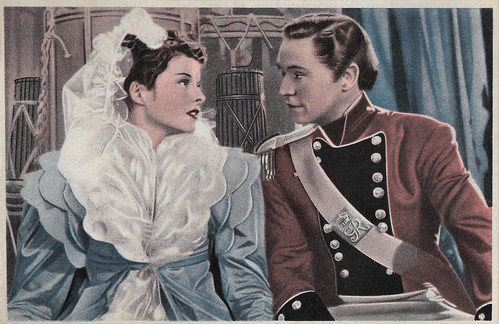

Italian postcard by Generalcine, Roma / Off. Graf. 'La Lito', Milano. Photo: RKO Radio Pictures. Publicity still for Quality Street (George Stevens, 1937) with Franchot Tone.

British Art Photo postcard, no. 38-1.

American postcard by Coral-Lee, Rancho Cordova, CA, no. CL/Personality # 130. Photo: Douglas Kirkland.

Katharine Houghton Hepburn was born in 1907 in Hartford, Connecticut, U.S.A. Her father was a wealthy and prominent Connecticut surgeon, and her mother was a leader in the women's suffrage movement.

From early childhood, Hepburn was continually encouraged to expand her intellectual horizons, speak nothing but the truth, and keep herself in top physical condition at all times. She would apply all of these ingrained values to her acting career, which began in earnest after she graduated from Bryn Mawr College in 1928.

That year, she made her Broadway debut in 'Night Hostess', appearing under the alias Katharine Burns. Hepburn scored her first major Broadway success in 'The Warrior’s Husband' (1932), a comedy set in the land of the Amazons. Shortly thereafter, she was invited to Hollywood by RKO Radio Pictures.

Hepburn was an unlikely Hollywood star. Possessing a distinctive speech pattern and an abundance of quirky mannerisms, she earned unqualified praise from her admirers and unmerciful criticism from her detractors. Unabashedly outspoken and iconoclastic, she did as she pleased, refusing to grant interviews, wearing casual clothes at a time when actresses were expected to exude glamour 24 hours a day, and openly clashing with her more experienced coworkers whenever they failed to meet her standards.

She nonetheless made an impressive film debut in George Cukor’s A Bill of Divorcement (1932), a drama that also starred John Barrymore. Hepburn was then cast as an aviator in Dorothy Arzner’s Christopher Strong (1933). For her third film, Morning Glory (Lowell Sherman, 1933), Hepburn won an Academy Award for her portrayal of an aspiring actress.

British Real Photograph postcard, no. 40. A. Photo: Radio Pictures.

Italian postcard by B.F.F. (Ballerini & Fratini Firenze) Edit., no. 2737.

British postcard in the Filmshots series by British Weekly. Photo: Radio. Publicity still for Christopher Strong (Dorothy Arzner, 1933) with Colin Clive.

British postcard in the Filmshots series by British Weekly. Photo: Radio. Publicity still for Christopher Strong (Dorothy Arzner, 1933) with Colin Clive.

Dutch postcard by the Rialto Theatre, Amsterdam, 1934. Photo: Remaco Radio Picture. Publicity still for Little Women (George Cukor, 1933). In the picture are Katharine Hepburn, Joan Bennett, Frances Dee, Jean Parker and Spring Byington. The Dutch title of the film and the book by Louise M. Alcott is Onder moeders vleugels.

British postcard in the Film Partners Series, no. P. 183. Photo: RKO / Radio Pictures. Fred MacMurray and Katharine Hepburn in Alice Adams (George Stevens, 1935).

American postcard by Fotofolio, NY, NY, no. P101. Photo: Photoworld. Katharine Hepburn on the set of Sylvia Scarlett (George Cukor, 1935).

British postcard in the Picturegoer Series, no. 1045a. Photo: R.K.O. Radio.

However, Katharine Hepburn’s much-publicised return to Broadway, in 'The Lake' (1933), proved to be a flop. And while filmgoers enjoyed her performances in homespun entertainments such as Little Women (George Cukor, 1933) and Alice Adams (George Stevens, 1935), they were largely resistant to historical vehicles such as Mary of Scotland (John Ford, 1936), A Woman Rebels (Mark Sandrich, 1936), and Quality Street (George Stevens, 1937).

Hepburn recovered some lost ground with her sparkling performances in the screwball comedies Bringing Up Baby (Howard Hawks, 1938) and Holiday (George Cukor, 1938), both of which also starred Cary Grant. However, it was too late: a group of leading film exhibitors had already written off Hepburn as “box office poison.”

Undaunted, Hepburn accepted a role written specifically for her in Philip Barry’s 1938 Broadway comedy The Philadelphia Story, about a socialite whose ex-husband tries to win her back. Howard Hughes, Hepburn's partner at the time, sensed that the play could be her ticket back to Hollywood stardom and bought her the film rights before it even debuted on stage. It was a huge hit.

She chose to sell the rights to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Hollywood's number one studio, on the condition that she be the star. As part of the deal, she also received the director of her choice, George Cukor, and picked James Stewart and Cary Grant as co-stars. The Philadelphia Story (George Cukor, 1940) was a critical and commercial success, and it jump-started her Hollywood career. She continued to make periodic returns to the stage (notably as the title character in the 1969 Broadway musical Coco), but Hepburn remained essentially a film actor for the remainder of her career.

Hepburn was also responsible for the development of her next project, the romantic comedy Woman of the Year (George Stevens, 1942), about a political columnist and a sports reporter whose relationship is threatened by her self-centred independence. The idea for the film was proposed to her by Garson Kanin in 1941, who recalled how Hepburn contributed to the script. She presented the finished product to MGM and demanded $250,000—half for her, and half for the authors. Her terms accepted, Hepburn was also given the director and co-star of her choice, George Stevens and Spencer Tracy. Woman of the Year was another success. Critics praised the chemistry between the stars.

Italian postcard by Ballerini & Fratini, Firenze, no. 2544. Photo: RKO / Generalcine. Katharine Hepburn in Quality Street (George Stevens, 1937). Collection: Marlene Pilaete.

French postcard in the Collection 'Portraits de Cinema' (4th series, no. 2) by Editions Admira & Chapman Collection / SNAP Photos / Cosmos, no. PHN 662, 1989. Cary Grant and Katharine Hepburn in Bringing Up Baby (Howard Hawks, 1938).

French postcard by A.N., Paris, Paris, no. 996.

French postcard by Edition Chantal, Paris, no. 77. Photo: R.K.O.

French postcard by Viny, no. 2131. Photo: R.K.O.

Dutch postcard by S & v. H., Amsterdam.

French postcard by Editions P.I., no. 206. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1950. Although the postcard was produced in 1950, the photo was taken much earlier, probably for The Philadelphia Story (George Cukor, 1940).

Katharine Hepburn's stature increased in the following decades as she chalked up such cinematic triumphs as John Huston’s The African Queen (1951), in which she played a missionary who escapes German troops with the aid of a riverboat captain (Humphrey Bogart), and David Lean’s Summertime (1955), a love story set in Venice. Hepburn received an Academy Award nomination for the second year running for her work opposite Burt Lancaster in The Rainmaker (Joseph Anthony, 1956). Again she played a lonely woman empowered by a love affair, and it became apparent that Hepburn had found a niche in playing 'love-starved spinsters' that critics and audiences enjoyed.

After two years away from the screen, Hepburn starred in a film adaptation of Tennessee Williams' controversial play Suddenly, Last Summer (1959) with Elizabeth Taylor and Montgomery Clift. She clashed with director Joseph L. Mankiewicz during filming, which culminated with her spitting at him in disgust. The picture was a financial success, and her work as creepy aunt Violet Venable gave Hepburn her eighth Oscar nomination. In Long Day’s Journey into Night (Sidney Lumet, 1962), an adaptation of Eugene O’Neill’s acclaimed play, Hepburn was cast as a drug-addicted mother, opposite Ralph Richardson, Jason Robards and Dean Stockwell. Long Day's Journey Into Night earned Hepburn an Oscar nomination and the Best Actress Award at the Cannes Film Festival. It remains one of her most praised performances.

Katharine Hepburn won a second Academy Award for Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (Stanley Kramer, 1967), a dramedy about interracial marriage; a third for The Lion in Winter (Anthony Harvey, 1968), in which she played Eleanor of Aquitaine opposite Peter O'Toole as King Henry II; and an unprecedented fourth Oscar for On Golden Pond (Mark Rydell, 1981), about long-married New Englanders (Hepburn and Henry Fonda). Her 12 Academy Award nominations also set a record, which stood until 2003, when broken by Meryl Streep. In addition, Hepburn appeared frequently on television in the 1970s and 1980s. She was nominated for an Emmy Award for her memorable portrayal of Amanda Wingfield in Tennessee Williams’s The Glass Menagerie (Anthony Harvey, 1973), and she won the award for her performance opposite Laurence Olivier in Love Among the Ruins (1975), which reunited her with her favourite director, George Cukor.

Though hampered by a progressive neurological disease, Hepburn was nonetheless still active in the early 1990s, appearing prominently in films such as Love Affair (Glenn Gordon Caron, 1994), which was her last film. At 87 years old, she played a supporting role, alongside Annette Bening and Warren Beatty. It was the only film of Hepburn's career, other than the cameo appearance in Stage Door Canteen (Frank Borzage, 1943), in which she did not play a leading role. Hepburn was married once. In 1928, she wed Philadelphia broker Ludlow Ogden Smith, but the union was dissolved in 1934. While filming Woman of the Year in 1942, she began an enduring intimate relationship with her costar, Spencer Tracy, with whom she would appear in films such as Adam’s Rib (1949) and Pat and Mike (1952); both were directed by George Cukor.

Tracy and Hepburn never married — he was Roman Catholic and would not divorce his wife — but they remained close both personally and professionally until his death in 1967, just days after completing the filming of Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner. Hepburn had suspended her own career for nearly five years to nurse Tracy through what turned out to be his final illness. In 1999, the American Film Institute named Hepburn the top female American screen legend of all time. She wrote several memoirs, including 'Me: Stories of My Life' (1991). Katharine Hepburn died in 2003 in Old Saybrook, Connecticut. She was 96.

Belgian postcard by Editions L.A.B., Bruxelles, no. 1035. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Katharine Hepburn, as Chinese character Jade Tan, in Dragon Seed (Harold S. Bucquet, Jack Conway, 1944). Collection: Marlene Pilaete.

Belgian Collectors Card by Kwatta, Bois d'Haine, no. C. 159. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Publicity still for Dragon Seed (Harold S. Bucquet, Jack Conway, 1944) with Turhan Bey.

Belgian collectors card by Chocolaterie Clovis, Pepinster. Collection: Amit Benyovits. Katharine Hepburn in Song of Love (Clarence Brown, 1947).

Belgian collector card by Kwatta. Photo: M.G.M. Paul Henreid and Katharine Hepburn in Song of Love (Clarence Brown, 1947).

Belgian Collectors Card by Kwatta, Bois d'Haine. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Collection: Geoffrey Donaldson Institute.

Belgian Collectors Card by Kwatta, Bois d'Haine, no. C. 110. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Collection: Geoffrey Donaldson Institute.

French postcard by Editions P.I., no. 206. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. (Miraculously, the card has the same credits as this card).

American postcard by Classico San Francisco, no. 136-208. Photo: The Ludlow Collection. Katharine Hepburn and Humphrey Bogart in The African Queen (John Huston, 1951).

Sources: Encyclopaedia Britannica, Wikipedia and IMDb.

French postcard by Viny, no. 31. Photo: R.K.O.

Belgian postcard by N.V. Victoria, Brussels, no. 12. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

British postcard by De Reszke Cigarettes, no. 34. Photo: Radio (RKO).

British postcard. Photo: RKO / Radio Pictures. Katharine Hepburn in Christopher Strong (Dorothy Arzner, 1933).

Italian postcard by Generalcine, Roma / Off. Graf. 'La Lito', Milano. Photo: RKO Radio Pictures. Publicity still for Quality Street (George Stevens, 1937) with Franchot Tone.

British Art Photo postcard, no. 38-1.

American postcard by Coral-Lee, Rancho Cordova, CA, no. CL/Personality # 130. Photo: Douglas Kirkland.

An unlikely Hollywood star

Katharine Houghton Hepburn was born in 1907 in Hartford, Connecticut, U.S.A. Her father was a wealthy and prominent Connecticut surgeon, and her mother was a leader in the women's suffrage movement.

From early childhood, Hepburn was continually encouraged to expand her intellectual horizons, speak nothing but the truth, and keep herself in top physical condition at all times. She would apply all of these ingrained values to her acting career, which began in earnest after she graduated from Bryn Mawr College in 1928.

That year, she made her Broadway debut in 'Night Hostess', appearing under the alias Katharine Burns. Hepburn scored her first major Broadway success in 'The Warrior’s Husband' (1932), a comedy set in the land of the Amazons. Shortly thereafter, she was invited to Hollywood by RKO Radio Pictures.

Hepburn was an unlikely Hollywood star. Possessing a distinctive speech pattern and an abundance of quirky mannerisms, she earned unqualified praise from her admirers and unmerciful criticism from her detractors. Unabashedly outspoken and iconoclastic, she did as she pleased, refusing to grant interviews, wearing casual clothes at a time when actresses were expected to exude glamour 24 hours a day, and openly clashing with her more experienced coworkers whenever they failed to meet her standards.

She nonetheless made an impressive film debut in George Cukor’s A Bill of Divorcement (1932), a drama that also starred John Barrymore. Hepburn was then cast as an aviator in Dorothy Arzner’s Christopher Strong (1933). For her third film, Morning Glory (Lowell Sherman, 1933), Hepburn won an Academy Award for her portrayal of an aspiring actress.

British Real Photograph postcard, no. 40. A. Photo: Radio Pictures.

Italian postcard by B.F.F. (Ballerini & Fratini Firenze) Edit., no. 2737.

British postcard in the Filmshots series by British Weekly. Photo: Radio. Publicity still for Christopher Strong (Dorothy Arzner, 1933) with Colin Clive.

British postcard in the Filmshots series by British Weekly. Photo: Radio. Publicity still for Christopher Strong (Dorothy Arzner, 1933) with Colin Clive.

Dutch postcard by the Rialto Theatre, Amsterdam, 1934. Photo: Remaco Radio Picture. Publicity still for Little Women (George Cukor, 1933). In the picture are Katharine Hepburn, Joan Bennett, Frances Dee, Jean Parker and Spring Byington. The Dutch title of the film and the book by Louise M. Alcott is Onder moeders vleugels.

British postcard in the Film Partners Series, no. P. 183. Photo: RKO / Radio Pictures. Fred MacMurray and Katharine Hepburn in Alice Adams (George Stevens, 1935).

American postcard by Fotofolio, NY, NY, no. P101. Photo: Photoworld. Katharine Hepburn on the set of Sylvia Scarlett (George Cukor, 1935).

British postcard in the Picturegoer Series, no. 1045a. Photo: R.K.O. Radio.

Box office poison

However, Katharine Hepburn’s much-publicised return to Broadway, in 'The Lake' (1933), proved to be a flop. And while filmgoers enjoyed her performances in homespun entertainments such as Little Women (George Cukor, 1933) and Alice Adams (George Stevens, 1935), they were largely resistant to historical vehicles such as Mary of Scotland (John Ford, 1936), A Woman Rebels (Mark Sandrich, 1936), and Quality Street (George Stevens, 1937).

Hepburn recovered some lost ground with her sparkling performances in the screwball comedies Bringing Up Baby (Howard Hawks, 1938) and Holiday (George Cukor, 1938), both of which also starred Cary Grant. However, it was too late: a group of leading film exhibitors had already written off Hepburn as “box office poison.”

Undaunted, Hepburn accepted a role written specifically for her in Philip Barry’s 1938 Broadway comedy The Philadelphia Story, about a socialite whose ex-husband tries to win her back. Howard Hughes, Hepburn's partner at the time, sensed that the play could be her ticket back to Hollywood stardom and bought her the film rights before it even debuted on stage. It was a huge hit.

She chose to sell the rights to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Hollywood's number one studio, on the condition that she be the star. As part of the deal, she also received the director of her choice, George Cukor, and picked James Stewart and Cary Grant as co-stars. The Philadelphia Story (George Cukor, 1940) was a critical and commercial success, and it jump-started her Hollywood career. She continued to make periodic returns to the stage (notably as the title character in the 1969 Broadway musical Coco), but Hepburn remained essentially a film actor for the remainder of her career.

Hepburn was also responsible for the development of her next project, the romantic comedy Woman of the Year (George Stevens, 1942), about a political columnist and a sports reporter whose relationship is threatened by her self-centred independence. The idea for the film was proposed to her by Garson Kanin in 1941, who recalled how Hepburn contributed to the script. She presented the finished product to MGM and demanded $250,000—half for her, and half for the authors. Her terms accepted, Hepburn was also given the director and co-star of her choice, George Stevens and Spencer Tracy. Woman of the Year was another success. Critics praised the chemistry between the stars.

Italian postcard by Ballerini & Fratini, Firenze, no. 2544. Photo: RKO / Generalcine. Katharine Hepburn in Quality Street (George Stevens, 1937). Collection: Marlene Pilaete.

French postcard in the Collection 'Portraits de Cinema' (4th series, no. 2) by Editions Admira & Chapman Collection / SNAP Photos / Cosmos, no. PHN 662, 1989. Cary Grant and Katharine Hepburn in Bringing Up Baby (Howard Hawks, 1938).

French postcard by A.N., Paris, Paris, no. 996.

French postcard by Edition Chantal, Paris, no. 77. Photo: R.K.O.

French postcard by Viny, no. 2131. Photo: R.K.O.

Dutch postcard by S & v. H., Amsterdam.

French postcard by Editions P.I., no. 206. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1950. Although the postcard was produced in 1950, the photo was taken much earlier, probably for The Philadelphia Story (George Cukor, 1940).

An unprecedented fourth Oscar

Katharine Hepburn's stature increased in the following decades as she chalked up such cinematic triumphs as John Huston’s The African Queen (1951), in which she played a missionary who escapes German troops with the aid of a riverboat captain (Humphrey Bogart), and David Lean’s Summertime (1955), a love story set in Venice. Hepburn received an Academy Award nomination for the second year running for her work opposite Burt Lancaster in The Rainmaker (Joseph Anthony, 1956). Again she played a lonely woman empowered by a love affair, and it became apparent that Hepburn had found a niche in playing 'love-starved spinsters' that critics and audiences enjoyed.

After two years away from the screen, Hepburn starred in a film adaptation of Tennessee Williams' controversial play Suddenly, Last Summer (1959) with Elizabeth Taylor and Montgomery Clift. She clashed with director Joseph L. Mankiewicz during filming, which culminated with her spitting at him in disgust. The picture was a financial success, and her work as creepy aunt Violet Venable gave Hepburn her eighth Oscar nomination. In Long Day’s Journey into Night (Sidney Lumet, 1962), an adaptation of Eugene O’Neill’s acclaimed play, Hepburn was cast as a drug-addicted mother, opposite Ralph Richardson, Jason Robards and Dean Stockwell. Long Day's Journey Into Night earned Hepburn an Oscar nomination and the Best Actress Award at the Cannes Film Festival. It remains one of her most praised performances.

Katharine Hepburn won a second Academy Award for Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (Stanley Kramer, 1967), a dramedy about interracial marriage; a third for The Lion in Winter (Anthony Harvey, 1968), in which she played Eleanor of Aquitaine opposite Peter O'Toole as King Henry II; and an unprecedented fourth Oscar for On Golden Pond (Mark Rydell, 1981), about long-married New Englanders (Hepburn and Henry Fonda). Her 12 Academy Award nominations also set a record, which stood until 2003, when broken by Meryl Streep. In addition, Hepburn appeared frequently on television in the 1970s and 1980s. She was nominated for an Emmy Award for her memorable portrayal of Amanda Wingfield in Tennessee Williams’s The Glass Menagerie (Anthony Harvey, 1973), and she won the award for her performance opposite Laurence Olivier in Love Among the Ruins (1975), which reunited her with her favourite director, George Cukor.

Though hampered by a progressive neurological disease, Hepburn was nonetheless still active in the early 1990s, appearing prominently in films such as Love Affair (Glenn Gordon Caron, 1994), which was her last film. At 87 years old, she played a supporting role, alongside Annette Bening and Warren Beatty. It was the only film of Hepburn's career, other than the cameo appearance in Stage Door Canteen (Frank Borzage, 1943), in which she did not play a leading role. Hepburn was married once. In 1928, she wed Philadelphia broker Ludlow Ogden Smith, but the union was dissolved in 1934. While filming Woman of the Year in 1942, she began an enduring intimate relationship with her costar, Spencer Tracy, with whom she would appear in films such as Adam’s Rib (1949) and Pat and Mike (1952); both were directed by George Cukor.

Tracy and Hepburn never married — he was Roman Catholic and would not divorce his wife — but they remained close both personally and professionally until his death in 1967, just days after completing the filming of Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner. Hepburn had suspended her own career for nearly five years to nurse Tracy through what turned out to be his final illness. In 1999, the American Film Institute named Hepburn the top female American screen legend of all time. She wrote several memoirs, including 'Me: Stories of My Life' (1991). Katharine Hepburn died in 2003 in Old Saybrook, Connecticut. She was 96.

Belgian postcard by Editions L.A.B., Bruxelles, no. 1035. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Katharine Hepburn, as Chinese character Jade Tan, in Dragon Seed (Harold S. Bucquet, Jack Conway, 1944). Collection: Marlene Pilaete.

Belgian Collectors Card by Kwatta, Bois d'Haine, no. C. 159. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Publicity still for Dragon Seed (Harold S. Bucquet, Jack Conway, 1944) with Turhan Bey.

Belgian collectors card by Chocolaterie Clovis, Pepinster. Collection: Amit Benyovits. Katharine Hepburn in Song of Love (Clarence Brown, 1947).

Belgian collector card by Kwatta. Photo: M.G.M. Paul Henreid and Katharine Hepburn in Song of Love (Clarence Brown, 1947).

Belgian Collectors Card by Kwatta, Bois d'Haine. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Collection: Geoffrey Donaldson Institute.

Belgian Collectors Card by Kwatta, Bois d'Haine, no. C. 110. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Collection: Geoffrey Donaldson Institute.

French postcard by Editions P.I., no. 206. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. (Miraculously, the card has the same credits as this card).

American postcard by Classico San Francisco, no. 136-208. Photo: The Ludlow Collection. Katharine Hepburn and Humphrey Bogart in The African Queen (John Huston, 1951).

Sources: Encyclopaedia Britannica, Wikipedia and IMDb.

1 comment:

Thank you for this wonderful post. She got her start in 1932 at the Croton River Playhouse.

Post a Comment