Corinne Griffith (1894–1979) was dubbed 'The Orchid Lady of the Screen'. She was one of the most popular American film actresses of the 1920s and widely considered the most beautiful star of the silent screen. While she started out at Vitagraph in 1916, she became a very popular actress at First National Pictures. She was nominated for the Oscar for Best Actress for The Divine Lady (1929). When sound film set in, Griffith stopped acting and became a successful writer and businesswoman.

French postcard by Editions Cinémagazine, no. 19. Photo: First National. Corinne Griffith in The Divine Lady (Frank Lloyd, 1929).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 3679/1, 1928-1929. Photo: Defina / First National. Corinne Griffith in The Divine Lady (Frank Lloyd, 1929).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 3679/2, 1928-1929. Photo: Defina / First National. Corinne Griffith in The Divine Lady (Frank Lloyd, 1929).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 103/5, 1928-1929. Photo: Defina / First National. Corinne Griffith in The Divine Lady (Frank Lloyd, 1929).

Corinne Mae Griffith was born in 1896 in Texarkana, Texas, as the daughter of John Lewis Griffin, a Methodist minister, and Ambolina (Ambolyn) Ghio Griffin. She was educated in the Sacred Heart Convent school in New Orleans and worked as a dancer before she began her acting career.

She signed a studio contract with Vitagraph in 1916 and made quite a few films there, e.g. opposite the male lead at Vitagraph then, Earle Williams. By 1920 she had become a well-known film star herself at Vitagraph, known as 'The Orchid Lady of the Screen'. Able to command her salaries, she left Vitagraph for First National Pictures in 1923, where her salaries were raised from 2.500 dollars a week in 1923 to 10.000 a week in 1927. In contrast to her ethereal screen image, Griffith negotiated each of her contracts personally and also personally dealt with the issue of her high salaries.

By the mid-1920s, she was considered Hollywood's richest woman next to Mary Pickford. In addition, already at Vitagraph, she could choose from three leading men and three directors. Also, she obtained decent working hours for herself on shooting days, which was uncommon in those years.

As Tom Slater writes in his biography on Women Film Pioneers Project, "A great beauty and comic talent, Griffith also played dramatic roles in which her character faced major decisions affecting her life and many others. Altogether, this body of work reveals the centrality and complexity of women’s roles in the post-Victorian consumer society.

In The Common Law (1923), Classified (1925), and The Garden of Eden (1928), directed by Lewis Milestone, Griffith must endure male lechery while attempting to earn a living and find romance. In Single Wives (1924), Déclassée (1925), and Three Hours (1927), she played wives involved in traumatic searches for love and meaning due to spousal abuse and neglect. In Black Oxen (1923), Griffith plays a highly unusual character for the twenties, or, indeed, probably any era, a woman who rejects romance for a political career."

Spanish postcard by La Novela Semanal Cinematografica, no. 87.

British postcard by Cinema Chat. Photo: Vitagraph.

Belgian postcard by S. A. Cacao et Chocolat Kivou, Vilvorde / N. V. Cacao en Chocolade Kivou, Vilvoorde. Photo: United Artists.

British postcard in the Pictures Portrait Gallery series by Pictures Ltd., London, no. 10/202. Sent by mail in 1931.

During her Vitagraph years, Corinne Griffith modestly lived at the Hotel des Artistes, while she would buy a large home when working at First National. Moreover, Slater reveals that in 1926, Griffith paid $185,000 for two properties in downtown Beverly Hills. This property would become the basis for a second career in real estate and a fabulous personal fortune.

By consequence, she became the first woman to address the National Realty Board in the early 1950s and campaigned throughout that decade to repeal the federal income tax. At one stage, Griffith owned four complete office buildings in Los Angeles. She was the executive producer of eleven of her films starting with Single Wives (George Archainbaud, 1924) and ending with Three Hours (James Flood, 1927).

In 1929, Griffith was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actress for her performance in Frank Lloyd's The Divine Lady (1929), a historical drama about the lives of Lady Emma Hamilton and Admiral Nelson. This was an American Vitaphone sound film with a synchronised musical score, sound effects, and some synchronised singing, but no spoken dialogue. Griffith played the female lead of Lady Hamilton, opposite Victor Varconi as Horatio Nelson.

Anthony Slide argues in 'Silent Players' that The Divine Lady was even more fitted to end the silent film era than F. W. Murnau's masterpiece Sunrise (1928): "It is even better that silent film came to a close with the brilliant romanticism of Corinne Griffith's The Divine Lady, which is exemplary of the best in direction (by Frank Lloyd), scripting (by Agnes Christine Johnston), cinematography (by John Seitz), and above all is dominated by a lyrical performance of its star." Slide's assessment is supported by the fact that The Divine Lady received Oscars for photography and direction.

In 1930, Griffith's first real sound film, Lilies of the Field, (Alexander Korda, 1930) with Ralph Forbes, was released. Her voice did not record well and The New York Times stated that she "talked through her nose". The film was a box office flop, as was her next film, Back Pay (William A. Seiter, 1930). First National paid the actress $ 250,000 to terminate her contract with the studio. Griffith made another film in the UK for Paramount-British Lily Christine (Paul L. Stein, 1932) opposite Colin Clive, and in 1935-1936, she did a theatre tour of Noël Coward 's 'Design for Living'. After the tour was finished, she retired from acting.

Swedish postcard by Förlag Nordisk Konst, Stockholm, no. 1300.

French postcard by A.N. (A. Noyer), Paris, no. 124. Photo: Bird. Corinne Griffith in Black Oxen (Frank Lloyd, 1923).

Danish postcard by Eneret, no. 725. Photo: First National. Corinne Griffith and Milton Sills in Single Wives (George Archainbaud, 1924).

British postcard in the Picturegoer Series, London, no. 62.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, Berlin, no. 897/2, 1925-1926. Photo: First National Pictures, New York.

After 1936, Corinne Griffith focused on her real estate and her writing. In the late 1950s, she returned one more time to the screen in the last film by actor-producer-director Hugo Haas, the low-budget social commentary Stars in Your Own Backyard. It was released as Paradise Alley (Hugo Haas, 1961), and at IMDb, the few reviewers are very positive about the film and about Griffith's performance.

One of the 13 books she published was her biography: 'Papa's Delicate Condition'. In 1963, the book was filmed as Papa's Delicate Condition (George Marshall, 1963). Griffith was not fond of the film. In the credits, her name was misspelt as "Corrine Griffith". She had unsuccessfully campaigned for Fred Astaire to play her father and was disappointed with the choice of Jackie Gleason.

In addition, she wrote the text of 'Hail to the Redskins', the official hymn of the American football team the Washington Redskins, with whose owner, George Preston Marshall, she was married from 1936 to 1958. She described the experiences around the team in another bestseller, 'My Life with the Redskins'. In the mid-1960s, Griffith's name reappeared in the headlines when she wanted to annul her short-term marriage with the 33-year-younger realtor and former Broadway actor Danny Scholl in court. During the process, she said that she was, in fact, the - at least 20 years younger and long-dead - sister of Corinne Griffith.

However, several colleagues from the silent film era, including Lois Wilson, Claire Windsor, and Betty Blythe, were able to prove in the course of the trial that the plaintiff would clearly be the real Corinne Griffith. Griffith pertained until her death she was her sister. Griffith was married four times, first to her frequent co-star Vitagraph actor-director Webster Campbell (1920-1923). Then she married theatre producer Walter Morosco (1924-1934 or 1928-1934), who produced Lewis Milestone's The Garden of Eden, the sole film to come out of their short-lived joint production company Corinne Griffith Productions.

Her third husband was George Marshall (1936-1958), founder and longtime owner of the Washington Redskins. At the age of 71, she married realtor and Broadway actor Dan Scholl in 1965. They separated after six weeks and, following a messy and much-publicised court battle, they were divorced. Griffith had no children of her own but had adopted two girls, Pamela and Cynthia. Apart from real estate, she developed as a writer, painter, and composer. When she passed away in 1979, at her mansion in Beverly Hills, Corinne Griffith left behind an estate of about $ 150 million. A star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, 1560 Wine Street, is a reminder of the actress. Tom Tryon wrote a novella, Fedora, based on Griffith's claim that she had taken the place of the real actress. It was filmed by Billy Wilder as Fedora (1978) starring Hildegard Knef and Marthe Keller.

French postcard by Editions Cinémagazine, no. 316.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, Berlin, no. 1873/1, 1927-1928. Photo: First National.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 4090/2, 1929-1930. Photo: Defina / First National.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 4945/2, 1929-1930. Photo: Defina / First National.

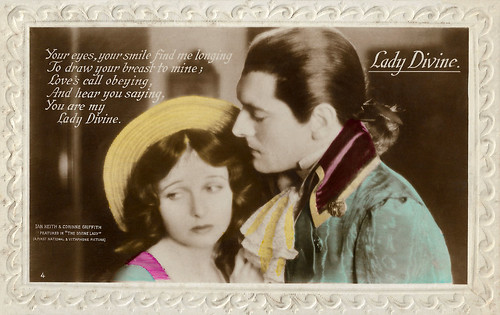

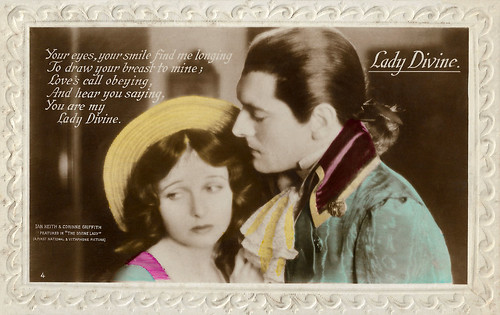

British postcard by Max Kracke & Co, London, in the Talkie Song Series, no. 4. Photo: First National. Corinne Griffith and Ian Keith in The Divine Lady (Frank Lloyd, 1929). Caption: Lady Divine. Your eyes, your smile find me longing, To draw your breast to mine; Love's call obeying, And hear you saying, You are my Lady Divine.

Sources: Anthony Slide (Silent Players), Tom Slater (Women Film Pioneers Project), Tim Lussier (Silents are Golden - page now defunct), Wikipedia (German and English), and IMDb.

This post was last updated on 15 July 2024.

French postcard by Editions Cinémagazine, no. 19. Photo: First National. Corinne Griffith in The Divine Lady (Frank Lloyd, 1929).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 3679/1, 1928-1929. Photo: Defina / First National. Corinne Griffith in The Divine Lady (Frank Lloyd, 1929).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 3679/2, 1928-1929. Photo: Defina / First National. Corinne Griffith in The Divine Lady (Frank Lloyd, 1929).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 103/5, 1928-1929. Photo: Defina / First National. Corinne Griffith in The Divine Lady (Frank Lloyd, 1929).

A highly unusual character for the 1920s

Corinne Mae Griffith was born in 1896 in Texarkana, Texas, as the daughter of John Lewis Griffin, a Methodist minister, and Ambolina (Ambolyn) Ghio Griffin. She was educated in the Sacred Heart Convent school in New Orleans and worked as a dancer before she began her acting career.

She signed a studio contract with Vitagraph in 1916 and made quite a few films there, e.g. opposite the male lead at Vitagraph then, Earle Williams. By 1920 she had become a well-known film star herself at Vitagraph, known as 'The Orchid Lady of the Screen'. Able to command her salaries, she left Vitagraph for First National Pictures in 1923, where her salaries were raised from 2.500 dollars a week in 1923 to 10.000 a week in 1927. In contrast to her ethereal screen image, Griffith negotiated each of her contracts personally and also personally dealt with the issue of her high salaries.

By the mid-1920s, she was considered Hollywood's richest woman next to Mary Pickford. In addition, already at Vitagraph, she could choose from three leading men and three directors. Also, she obtained decent working hours for herself on shooting days, which was uncommon in those years.

As Tom Slater writes in his biography on Women Film Pioneers Project, "A great beauty and comic talent, Griffith also played dramatic roles in which her character faced major decisions affecting her life and many others. Altogether, this body of work reveals the centrality and complexity of women’s roles in the post-Victorian consumer society.

In The Common Law (1923), Classified (1925), and The Garden of Eden (1928), directed by Lewis Milestone, Griffith must endure male lechery while attempting to earn a living and find romance. In Single Wives (1924), Déclassée (1925), and Three Hours (1927), she played wives involved in traumatic searches for love and meaning due to spousal abuse and neglect. In Black Oxen (1923), Griffith plays a highly unusual character for the twenties, or, indeed, probably any era, a woman who rejects romance for a political career."

Spanish postcard by La Novela Semanal Cinematografica, no. 87.

British postcard by Cinema Chat. Photo: Vitagraph.

Belgian postcard by S. A. Cacao et Chocolat Kivou, Vilvorde / N. V. Cacao en Chocolade Kivou, Vilvoorde. Photo: United Artists.

British postcard in the Pictures Portrait Gallery series by Pictures Ltd., London, no. 10/202. Sent by mail in 1931.

A fabulous personal fortune

During her Vitagraph years, Corinne Griffith modestly lived at the Hotel des Artistes, while she would buy a large home when working at First National. Moreover, Slater reveals that in 1926, Griffith paid $185,000 for two properties in downtown Beverly Hills. This property would become the basis for a second career in real estate and a fabulous personal fortune.

By consequence, she became the first woman to address the National Realty Board in the early 1950s and campaigned throughout that decade to repeal the federal income tax. At one stage, Griffith owned four complete office buildings in Los Angeles. She was the executive producer of eleven of her films starting with Single Wives (George Archainbaud, 1924) and ending with Three Hours (James Flood, 1927).

In 1929, Griffith was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actress for her performance in Frank Lloyd's The Divine Lady (1929), a historical drama about the lives of Lady Emma Hamilton and Admiral Nelson. This was an American Vitaphone sound film with a synchronised musical score, sound effects, and some synchronised singing, but no spoken dialogue. Griffith played the female lead of Lady Hamilton, opposite Victor Varconi as Horatio Nelson.

Anthony Slide argues in 'Silent Players' that The Divine Lady was even more fitted to end the silent film era than F. W. Murnau's masterpiece Sunrise (1928): "It is even better that silent film came to a close with the brilliant romanticism of Corinne Griffith's The Divine Lady, which is exemplary of the best in direction (by Frank Lloyd), scripting (by Agnes Christine Johnston), cinematography (by John Seitz), and above all is dominated by a lyrical performance of its star." Slide's assessment is supported by the fact that The Divine Lady received Oscars for photography and direction.

In 1930, Griffith's first real sound film, Lilies of the Field, (Alexander Korda, 1930) with Ralph Forbes, was released. Her voice did not record well and The New York Times stated that she "talked through her nose". The film was a box office flop, as was her next film, Back Pay (William A. Seiter, 1930). First National paid the actress $ 250,000 to terminate her contract with the studio. Griffith made another film in the UK for Paramount-British Lily Christine (Paul L. Stein, 1932) opposite Colin Clive, and in 1935-1936, she did a theatre tour of Noël Coward 's 'Design for Living'. After the tour was finished, she retired from acting.

Swedish postcard by Förlag Nordisk Konst, Stockholm, no. 1300.

French postcard by A.N. (A. Noyer), Paris, no. 124. Photo: Bird. Corinne Griffith in Black Oxen (Frank Lloyd, 1923).

Danish postcard by Eneret, no. 725. Photo: First National. Corinne Griffith and Milton Sills in Single Wives (George Archainbaud, 1924).

British postcard in the Picturegoer Series, London, no. 62.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, Berlin, no. 897/2, 1925-1926. Photo: First National Pictures, New York.

The real Corinne Griffith?

After 1936, Corinne Griffith focused on her real estate and her writing. In the late 1950s, she returned one more time to the screen in the last film by actor-producer-director Hugo Haas, the low-budget social commentary Stars in Your Own Backyard. It was released as Paradise Alley (Hugo Haas, 1961), and at IMDb, the few reviewers are very positive about the film and about Griffith's performance.

One of the 13 books she published was her biography: 'Papa's Delicate Condition'. In 1963, the book was filmed as Papa's Delicate Condition (George Marshall, 1963). Griffith was not fond of the film. In the credits, her name was misspelt as "Corrine Griffith". She had unsuccessfully campaigned for Fred Astaire to play her father and was disappointed with the choice of Jackie Gleason.

In addition, she wrote the text of 'Hail to the Redskins', the official hymn of the American football team the Washington Redskins, with whose owner, George Preston Marshall, she was married from 1936 to 1958. She described the experiences around the team in another bestseller, 'My Life with the Redskins'. In the mid-1960s, Griffith's name reappeared in the headlines when she wanted to annul her short-term marriage with the 33-year-younger realtor and former Broadway actor Danny Scholl in court. During the process, she said that she was, in fact, the - at least 20 years younger and long-dead - sister of Corinne Griffith.

However, several colleagues from the silent film era, including Lois Wilson, Claire Windsor, and Betty Blythe, were able to prove in the course of the trial that the plaintiff would clearly be the real Corinne Griffith. Griffith pertained until her death she was her sister. Griffith was married four times, first to her frequent co-star Vitagraph actor-director Webster Campbell (1920-1923). Then she married theatre producer Walter Morosco (1924-1934 or 1928-1934), who produced Lewis Milestone's The Garden of Eden, the sole film to come out of their short-lived joint production company Corinne Griffith Productions.

Her third husband was George Marshall (1936-1958), founder and longtime owner of the Washington Redskins. At the age of 71, she married realtor and Broadway actor Dan Scholl in 1965. They separated after six weeks and, following a messy and much-publicised court battle, they were divorced. Griffith had no children of her own but had adopted two girls, Pamela and Cynthia. Apart from real estate, she developed as a writer, painter, and composer. When she passed away in 1979, at her mansion in Beverly Hills, Corinne Griffith left behind an estate of about $ 150 million. A star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, 1560 Wine Street, is a reminder of the actress. Tom Tryon wrote a novella, Fedora, based on Griffith's claim that she had taken the place of the real actress. It was filmed by Billy Wilder as Fedora (1978) starring Hildegard Knef and Marthe Keller.

French postcard by Editions Cinémagazine, no. 316.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, Berlin, no. 1873/1, 1927-1928. Photo: First National.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 4090/2, 1929-1930. Photo: Defina / First National.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 4945/2, 1929-1930. Photo: Defina / First National.

British postcard by Max Kracke & Co, London, in the Talkie Song Series, no. 4. Photo: First National. Corinne Griffith and Ian Keith in The Divine Lady (Frank Lloyd, 1929). Caption: Lady Divine. Your eyes, your smile find me longing, To draw your breast to mine; Love's call obeying, And hear you saying, You are my Lady Divine.

Sources: Anthony Slide (Silent Players), Tom Slater (Women Film Pioneers Project), Tim Lussier (Silents are Golden - page now defunct), Wikipedia (German and English), and IMDb.

This post was last updated on 15 July 2024.

No comments:

Post a Comment