Alice Terry (1900–1987) was an American film actress and director, who appeared in almost 40 films between 1916 and 1933. Though a brunette, Terry's trademark look was her blonde hair, for which she wore wigs from 1920 onwards. Her most acclaimed role is the leading lady in The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (Rex Ingram, 1921) starring Rudolph Valentino. Ingram, who married her in 1921, would shoot her in many of his films and often paired her to Ramon Novarro. Terry proved also in films without her husband’s direction she was a legitimate star. In 1923 the couple moved to the French Riviera, where they set up a small studio in Nice and made several films on location in North Africa, Spain, and Italy.

French postcard by Europe, no. 535. Photo: Regal Film / United Artists.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 679/4. Lewis Stone as Rudolph Rassendyll and Alice Terry as Princess Flavia in The Prisoner of Zenda (Rex Ingram, 1922).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, Berlin, no. 807/1, 1925-1926. Photo: Bafag. With Rex Ingram.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 842/2, 1925-1926. Photo: British-American Film A.G. (Bafag).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 3255/1, 1928-1929. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM). Alice Terry in Lovers? (John M. Stahl, 1927).

Alice Terry was born as Alice Frances Taaffe in 1899 in Vincennes, Indiana, USA.

Alice started as an extra in films at age 15 to help her family financially. She made her film debut in Not My Sister (Charles Giblyn, 1916), opposite Bessie Barriscale and William Desmond Taylor. It was produced by legendary film pioneer Thomas Ince. She worked in "Inceville", Ince's studio, and would appear as an extra as several characters in his pacifist allegorical drama Civilization (Reginald Barker, Thomas H. Ince, 1916). The film was a big-budget spectacle that was compared to both The Birth of a Nation (D.W. Griffith, 1915) and the paintings of Jean-François Millet. Civilization was a popular success and was credited by the Democratic National Committee with helping to re-elect Woodrow Wilson as the U.S. President in 1916.

She was shy and was also interested in other motion picture jobs, considering work as a script girl or a cutter behind the camera as preferable to performing in front of it. For two years Alice worked in cutting rooms at Famous-Players-Lasky. This work would help her later on when she worked with Rex Ingram on his films. It was while she was working as an extra on The Devil's Passkey (Erich von Stroheim, 1920) that Alice was first noticed, by director Erich von Stroheim. Sadly, her insecurity caused her to rapidly leave the Universal lot. She never even stopped to pick up her paycheck.

In 1917, she had met director Rex Ingram. Ingram promoted her to small parts in his early Metro Pictures films in the late teens. He also directed her physical transformation, overseeing a program of weight loss and dental repair, and creating “Alice Terry” — both the name and the image — as his protege. He gave her her first significant role in Hearts Are Trumps (Rex Ingram, 1920). It was during preparation for this role that Alice discovered what would become her trademark.

IMDb: 'She was putting on her make-up and saw a blonde wig on the table next to her. She put it on but thought it looked silly. Just then the director Rex Ingram (who was already an admirer, both personally and professionally) walked in and saw her in it. He insisted she wear it in the film. Alice wasn't convinced until she saw the rushes the next day. "When I appeared on the screen, I looked so different, and from that time I never got rid of the wig."' Wikipedia adds that she put on her first blonde wig in Hearts Are Trumps (1920) 'to look different from Francelia Billington, the other actress in the film.'

Ingram and Terry would marry in 1921. It was also in 1921 that Alice would gain acclaim as Marguerite in The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1921), with the blonde wig. Often regarded as one of the first true anti-war films, it had a huge cultural impact and became the top-grossing film of 1921, beating out Charlie Chaplin's The Kid (1921). The film turned then-little-known actor Rudolph Valentino into a superstar and associated him with the image of the Latin Lover. The film also inspired a tango craze and such fashion fads as gaucho pants.

For her husband, she would continue to play the heroine is such masterpieces as The Prisoner of Zenda (Rex Ingram, 1922) in which she appeared as Princess Flavia opposite Lewis Stone and the upcoming Ramon Novarro as the bad guy, and Scaramouche (Rex Ingram, 1923), now featuring Ramon Novarro. Both films were smash hits. Heidi Kenaga at Women Film Pioneer's Project: '“Rex and His Queen” were one of the more celebrated director-actress teams of the 1920s, but there are indications that performing was only one dimension of Terry’s contribution to their work together.'

In 1924 and 1925 the marriage between Terry and Ingram was in jeopardy, according to Wikipedia, and in that time period she worked under other directors. Alice worked on five films, and particularly her roles in Any Woman (Henry King, 1925) and Sackcloth and Scarlet (Henry King, 1925), both by Paramount Pictures, proved that Alice was a legitimate star away from her husband. She also would make the Western melodrama The Great Divide (Reginald Barker, 1924) with Conway Tearle and Wallace Beery.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 1033/2. Photo: Phoebus Film. Alice Terry in Scaramouche (Rex Ingram, 1923).

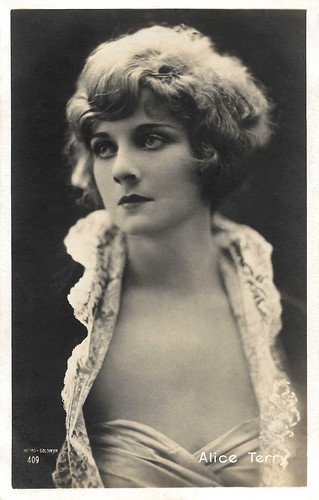

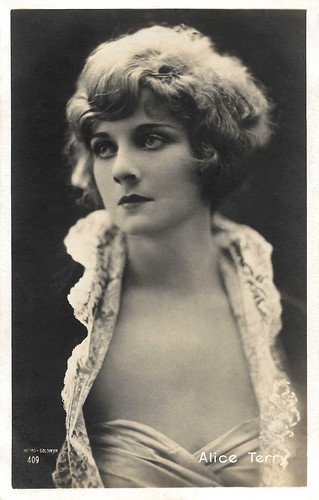

Italian postcard by G. Vettori, Bologna, no. 409. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn. Alice Terry in Scaramouche (Rex Ingram, 1923).

Italian postcard by G. Vettori, Bologna, no. 409. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn.

Italian postcard by G.B. Falci, Milano, no. 447. Ramon Novarro and Alice Terry in the Metro Pictures production Scaramouche (Rex Ingram, 1923).

Italian postcard in the Serie d'Oro by Casa Editrice Ballerini & Fratini, Firenze, no. 245a. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Alice Terry and Ivan Petrovich in The Magician (Rex Ingram, 1926).

In 1924, Metro would merge into the new MGM and both Rex Ingram and Alice Terry would work there. She would be directed again by Ingram in The Arab (1924), which was filmed in North Africa and owed much to the influence of screen idol Valentino. When they got back together, Terry took on a more behind-the-scenes role. During the making of The Arab (Rex Ingram, 1924) in Tunisia, they met a street child named Kada-Abd-el-Kader, whom they adopted upon learning that he was an orphan. Allegedly, el-Kader misrepresented his age to make himself seem younger to his adoptive parents.

In 1925 Ingram co-directed Ben-Hur, filming parts of it in Italy. The two decided to move to the French Riviera, where they set up a small studio in Nice and started to make films on location in North Africa, Spain, and Italy. Alice would get her chance to play the wicked woman in Mare Nostrum (Rex Ingram, 1926). Filmed in Italy and Spain, this film was both a critical and financial success for the couple.

Ingram would make his third independent film in Italy when he directed Alice in The Garden of Allah (Rex Ingram, 1927). Later that year, Alice would be reunited with Ramon Novarro in Lovers? (John M. Stahl, 1927), but the film would not be as well received as their earlier films.

When sound came to the screen Alice and Rex retired. Her last film appearance was in the sound film Baroud (1933) starring Pierre Batcheff, which she also co-directed with husband. Alice helped so much that she was named co-director and she directed all the scenes Ingram himself appeared in. Wikipedia: 'Baroud (Rex Ingram, Alice Terry, 1933) highlighted Alice's ability as an all around filmmaker but she never took that further.'

Terry and Ingram retired in the 1930s and took up painting. Once Terry and Ingram moved back to the United States they started having problems with their adopted son, Kada-Abd-el-Kader. According to Wikipedia, He 'began associating with fast women and fast cars throughout the San Fernando Valley.' Terry and Ingram sent him back to Morocco 'to finish school.' Kada-Abd-el-Kader never went back to school, but he later became a tourist guide in Morocco and Algiers. El-Kader would always tell tourists that he was the adopted son of Rex Ingram and Alice Terry

In 1950, Rex Ingram passed away. Terry was open-minded and she invited four of Rex's mistresses to his funeral. Wikipedia quotes her saying: 'Who cares, I'm the only one that can call herself Mrs. Rex Ingram.' A year later, when Columbia released Valentino (Lewis Allen, 1951), featuring Eleanor Parker and Anthony Dexter, Alice Terry filed suit against Columbia and the producers because of the way the film "falsely portrayed a clandestine relationship between Valentino and Terry". Columbia settled out of court for an undisclosed sum.

In 1960, she was awarded a Star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 6628 Hollywood Boulevard in Hollywood, California. Terry was still active in the 1970s. She loved hosting Sunday afternoon parties and going out to dinner in extravagant, floor length mink coats. Alzheimer's put a stop to Terry's parties and fun. Following her death in 1987 in Burbank, California by pneumonia, Alice Terry was interred at Vahalla Memorial Park Cemetery in North Hollywood.

Alice Terry made 29 films, not counting four appearances as an extra. Of these 29, 17 are lost films. Six exist in archives around the world and six survive on video and on television broadcast release.

About her part in Rex Ingram's films, Picture Play commented in a 1924 article, she was set apart by “her unrestrained enthusiasm for her husband, her unqualified praise for his work, with absolutely no mention of her own minor but definite achievements.” Heidi Kenaga gives her at Women Film Pioneer's Project full credit for the films she made with Ingram and cites film historian Anthony Slide: 'although Terry is only given on-screen credit for Baroud — a sound film made after Ingram’s heyday and outside the US studio system — it is possible she also co-directed some parts of Ingram’s motion pictures between 1921 and 1929.'

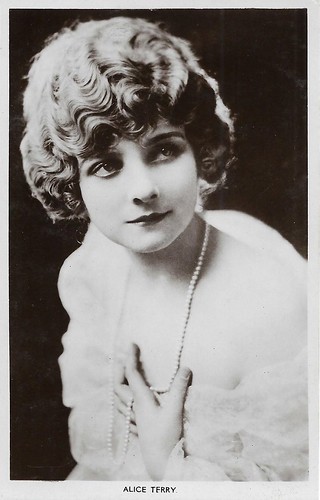

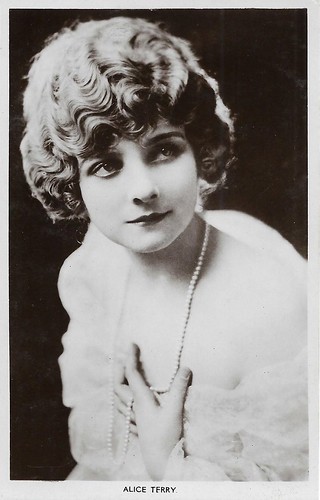

British postcard in the Picturegoer Series, London, no. 19.

German postcard. by Ross Verlag, no. 1449/2, 1927-1928. Photo: Angelo Photos.

German postcard. by Ross Verlag, no. 1449/3, 1927-1928. Photo: Angelo Photos.

Austrian postcard by Iris Verlag, no. 369/2, 1927-1928. Photo: Fanamet-Film.

French postcard by Editions Cinémagazine, no. 193. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Alice Terry in The Garden of Allah (Rex Ingram, 1927).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 4854/1, 1929-1930. Photo: United Artists. Ivan Petrovich and Alice Terry in The Three Passions (Rex Ingram, 1928). Collection: Geoffrey Donaldson Institute.

Sources: Heidi Kenaga (Women Film Pioneer's Project), Tony Fontana (IMDb), Wikipedia and IMDb.

French postcard by Europe, no. 535. Photo: Regal Film / United Artists.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 679/4. Lewis Stone as Rudolph Rassendyll and Alice Terry as Princess Flavia in The Prisoner of Zenda (Rex Ingram, 1922).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, Berlin, no. 807/1, 1925-1926. Photo: Bafag. With Rex Ingram.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 842/2, 1925-1926. Photo: British-American Film A.G. (Bafag).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 3255/1, 1928-1929. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM). Alice Terry in Lovers? (John M. Stahl, 1927).

Rex and His Queen

Alice Terry was born as Alice Frances Taaffe in 1899 in Vincennes, Indiana, USA.

Alice started as an extra in films at age 15 to help her family financially. She made her film debut in Not My Sister (Charles Giblyn, 1916), opposite Bessie Barriscale and William Desmond Taylor. It was produced by legendary film pioneer Thomas Ince. She worked in "Inceville", Ince's studio, and would appear as an extra as several characters in his pacifist allegorical drama Civilization (Reginald Barker, Thomas H. Ince, 1916). The film was a big-budget spectacle that was compared to both The Birth of a Nation (D.W. Griffith, 1915) and the paintings of Jean-François Millet. Civilization was a popular success and was credited by the Democratic National Committee with helping to re-elect Woodrow Wilson as the U.S. President in 1916.

She was shy and was also interested in other motion picture jobs, considering work as a script girl or a cutter behind the camera as preferable to performing in front of it. For two years Alice worked in cutting rooms at Famous-Players-Lasky. This work would help her later on when she worked with Rex Ingram on his films. It was while she was working as an extra on The Devil's Passkey (Erich von Stroheim, 1920) that Alice was first noticed, by director Erich von Stroheim. Sadly, her insecurity caused her to rapidly leave the Universal lot. She never even stopped to pick up her paycheck.

In 1917, she had met director Rex Ingram. Ingram promoted her to small parts in his early Metro Pictures films in the late teens. He also directed her physical transformation, overseeing a program of weight loss and dental repair, and creating “Alice Terry” — both the name and the image — as his protege. He gave her her first significant role in Hearts Are Trumps (Rex Ingram, 1920). It was during preparation for this role that Alice discovered what would become her trademark.

IMDb: 'She was putting on her make-up and saw a blonde wig on the table next to her. She put it on but thought it looked silly. Just then the director Rex Ingram (who was already an admirer, both personally and professionally) walked in and saw her in it. He insisted she wear it in the film. Alice wasn't convinced until she saw the rushes the next day. "When I appeared on the screen, I looked so different, and from that time I never got rid of the wig."' Wikipedia adds that she put on her first blonde wig in Hearts Are Trumps (1920) 'to look different from Francelia Billington, the other actress in the film.'

Ingram and Terry would marry in 1921. It was also in 1921 that Alice would gain acclaim as Marguerite in The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1921), with the blonde wig. Often regarded as one of the first true anti-war films, it had a huge cultural impact and became the top-grossing film of 1921, beating out Charlie Chaplin's The Kid (1921). The film turned then-little-known actor Rudolph Valentino into a superstar and associated him with the image of the Latin Lover. The film also inspired a tango craze and such fashion fads as gaucho pants.

For her husband, she would continue to play the heroine is such masterpieces as The Prisoner of Zenda (Rex Ingram, 1922) in which she appeared as Princess Flavia opposite Lewis Stone and the upcoming Ramon Novarro as the bad guy, and Scaramouche (Rex Ingram, 1923), now featuring Ramon Novarro. Both films were smash hits. Heidi Kenaga at Women Film Pioneer's Project: '“Rex and His Queen” were one of the more celebrated director-actress teams of the 1920s, but there are indications that performing was only one dimension of Terry’s contribution to their work together.'

In 1924 and 1925 the marriage between Terry and Ingram was in jeopardy, according to Wikipedia, and in that time period she worked under other directors. Alice worked on five films, and particularly her roles in Any Woman (Henry King, 1925) and Sackcloth and Scarlet (Henry King, 1925), both by Paramount Pictures, proved that Alice was a legitimate star away from her husband. She also would make the Western melodrama The Great Divide (Reginald Barker, 1924) with Conway Tearle and Wallace Beery.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 1033/2. Photo: Phoebus Film. Alice Terry in Scaramouche (Rex Ingram, 1923).

Italian postcard by G. Vettori, Bologna, no. 409. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn. Alice Terry in Scaramouche (Rex Ingram, 1923).

Italian postcard by G. Vettori, Bologna, no. 409. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn.

Italian postcard by G.B. Falci, Milano, no. 447. Ramon Novarro and Alice Terry in the Metro Pictures production Scaramouche (Rex Ingram, 1923).

Italian postcard in the Serie d'Oro by Casa Editrice Ballerini & Fratini, Firenze, no. 245a. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Alice Terry and Ivan Petrovich in The Magician (Rex Ingram, 1926).

The only Mrs. Rex Ingram

In 1924, Metro would merge into the new MGM and both Rex Ingram and Alice Terry would work there. She would be directed again by Ingram in The Arab (1924), which was filmed in North Africa and owed much to the influence of screen idol Valentino. When they got back together, Terry took on a more behind-the-scenes role. During the making of The Arab (Rex Ingram, 1924) in Tunisia, they met a street child named Kada-Abd-el-Kader, whom they adopted upon learning that he was an orphan. Allegedly, el-Kader misrepresented his age to make himself seem younger to his adoptive parents.

In 1925 Ingram co-directed Ben-Hur, filming parts of it in Italy. The two decided to move to the French Riviera, where they set up a small studio in Nice and started to make films on location in North Africa, Spain, and Italy. Alice would get her chance to play the wicked woman in Mare Nostrum (Rex Ingram, 1926). Filmed in Italy and Spain, this film was both a critical and financial success for the couple.

Ingram would make his third independent film in Italy when he directed Alice in The Garden of Allah (Rex Ingram, 1927). Later that year, Alice would be reunited with Ramon Novarro in Lovers? (John M. Stahl, 1927), but the film would not be as well received as their earlier films.

When sound came to the screen Alice and Rex retired. Her last film appearance was in the sound film Baroud (1933) starring Pierre Batcheff, which she also co-directed with husband. Alice helped so much that she was named co-director and she directed all the scenes Ingram himself appeared in. Wikipedia: 'Baroud (Rex Ingram, Alice Terry, 1933) highlighted Alice's ability as an all around filmmaker but she never took that further.'

Terry and Ingram retired in the 1930s and took up painting. Once Terry and Ingram moved back to the United States they started having problems with their adopted son, Kada-Abd-el-Kader. According to Wikipedia, He 'began associating with fast women and fast cars throughout the San Fernando Valley.' Terry and Ingram sent him back to Morocco 'to finish school.' Kada-Abd-el-Kader never went back to school, but he later became a tourist guide in Morocco and Algiers. El-Kader would always tell tourists that he was the adopted son of Rex Ingram and Alice Terry

In 1950, Rex Ingram passed away. Terry was open-minded and she invited four of Rex's mistresses to his funeral. Wikipedia quotes her saying: 'Who cares, I'm the only one that can call herself Mrs. Rex Ingram.' A year later, when Columbia released Valentino (Lewis Allen, 1951), featuring Eleanor Parker and Anthony Dexter, Alice Terry filed suit against Columbia and the producers because of the way the film "falsely portrayed a clandestine relationship between Valentino and Terry". Columbia settled out of court for an undisclosed sum.

In 1960, she was awarded a Star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 6628 Hollywood Boulevard in Hollywood, California. Terry was still active in the 1970s. She loved hosting Sunday afternoon parties and going out to dinner in extravagant, floor length mink coats. Alzheimer's put a stop to Terry's parties and fun. Following her death in 1987 in Burbank, California by pneumonia, Alice Terry was interred at Vahalla Memorial Park Cemetery in North Hollywood.

Alice Terry made 29 films, not counting four appearances as an extra. Of these 29, 17 are lost films. Six exist in archives around the world and six survive on video and on television broadcast release.

About her part in Rex Ingram's films, Picture Play commented in a 1924 article, she was set apart by “her unrestrained enthusiasm for her husband, her unqualified praise for his work, with absolutely no mention of her own minor but definite achievements.” Heidi Kenaga gives her at Women Film Pioneer's Project full credit for the films she made with Ingram and cites film historian Anthony Slide: 'although Terry is only given on-screen credit for Baroud — a sound film made after Ingram’s heyday and outside the US studio system — it is possible she also co-directed some parts of Ingram’s motion pictures between 1921 and 1929.'

British postcard in the Picturegoer Series, London, no. 19.

German postcard. by Ross Verlag, no. 1449/2, 1927-1928. Photo: Angelo Photos.

German postcard. by Ross Verlag, no. 1449/3, 1927-1928. Photo: Angelo Photos.

Austrian postcard by Iris Verlag, no. 369/2, 1927-1928. Photo: Fanamet-Film.

French postcard by Editions Cinémagazine, no. 193. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Alice Terry in The Garden of Allah (Rex Ingram, 1927).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 4854/1, 1929-1930. Photo: United Artists. Ivan Petrovich and Alice Terry in The Three Passions (Rex Ingram, 1928). Collection: Geoffrey Donaldson Institute.

Sources: Heidi Kenaga (Women Film Pioneer's Project), Tony Fontana (IMDb), Wikipedia and IMDb.

No comments:

Post a Comment