Snowfall can provide a lot of atmosphere for a film. But directors don't want to stand around and wait for the snowflakes. Since the dawn of cinema, filmmakers have been devising new ways to fake it. One early substance used was cotton, until a fireman in 1928 pointed out that it was a bad idea to cover a film set in a flammable material. He had another not-so-bright idea. Why not use asbestos? The idea gained momentum in Hollywood, and from the 1930s through the 1950s, asbestos was marketed as snow under the names "Pure White" and "Snow Drift." But a number of other materials were used over time to make it look as if it was snowy, even on a hot summer’s day on set.

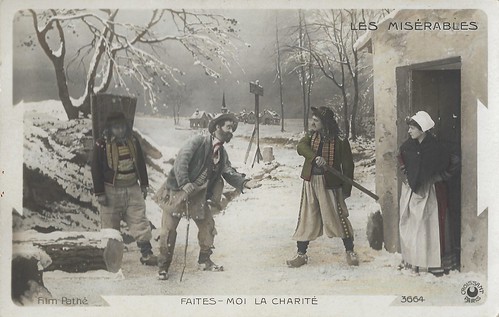

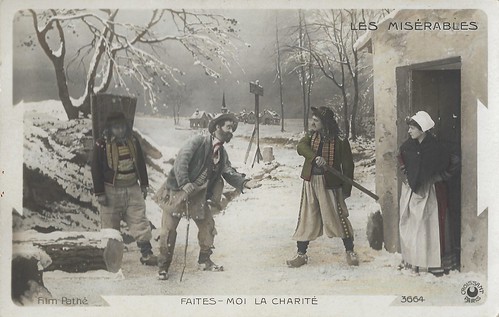

French postcard by Croisant, Paris, no. 3664. Photo: Film Pathé. Publicity still for Le chemineau/The Tramp (Albert Capellani, 1905), based on the first part of Victor Hugo's novel 'Les misérables'. It's winter, snow falls on the desolate countryside. An exhausted tramp in vain asks for an alimony from passers-by. Unclear is who the actors are, but the sets were created by Hugues Laurent.

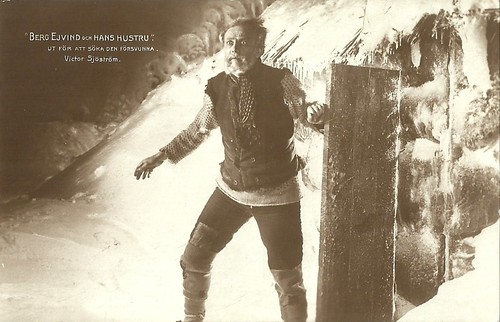

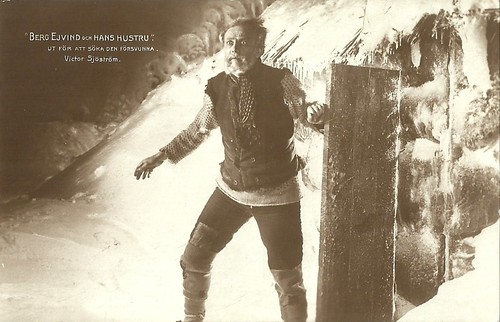

Swedish postcard by Nordisk Konst, Stockholm, no. 844/ 11. Photo: Svenska Biografteatern AB. Victor Sjöström in Berg-Ejvind och hans hustru/The Outlaw and His Wife (Victor Sjöström, 1918). Caption: Out to seek the lost.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 609/2. Photo: Messter-Film, Berlin. Henny Porten in the romantic comedy Ihr Sport/Her Sport (Rudolf Biebrach, 1919).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, Berlin, no. 760/6. Photo: Alex Binder. Pola Negri in Die Bergkatze/Wildcat (Ernst Lubitsch, 1921).

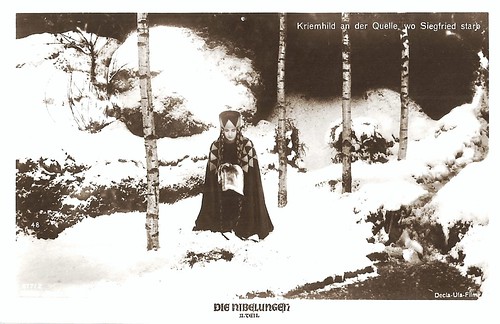

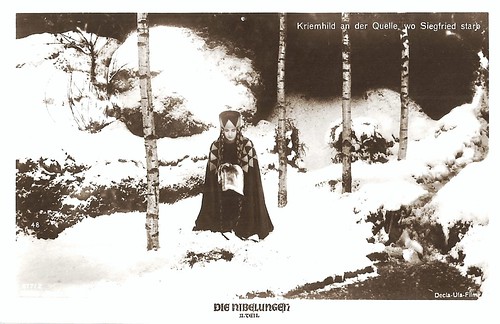

German postcard by Ross Verlag, Berlin, no. 677/2. Photo: Decla-Ufa-Film. Kriemhild (Margarete Schön) at the spring where Siegfried died in Die Nibelungen, II. Teil, Kriemhilds Rache/Kriemhild's Revenge (Fritz Lang, 1924).

French postcard by Hélio-Cachan. Photo: Charlie Chaplin in The Gold Rush (Charles Chaplin, 1925).

The Swedish silent classic Berg-Ejvind och hans hustru/The Outlaw and His Wife (Victor Sjöström, 1918) is based on 'Fjalla-Eyvind' (1911), a play by the Icelandic playwright Jóhann Sigurjónsson. The film is set in Iceland, but was filmed in the North of Sweden, at Åre and Abisko, where fake snow was not needed. The film is not only a realist vision of the hardship of nature but also of the intolerance of humans. When the film came out, not only Sjöström's direction but also the cinematography of Julius Jaenzon was praised. French critic Louis Delluc called it the most beautiful film he saw until then, praising the director, the two leading actors and the landscape as 'third protagonist'.

In The Gold Rush (1925), Charles Chaplin found inspiration in the historical Klondike Gold Rush, and led him to drag the production's cast and crew to snowy, rustic Trukee, Nevada to serve as the scenic Chilkoot Pass in Alaska. Chaplin found directing his film difficult to control in the frigid conditions, and after coming down with the flu, he agreed to return to Hollywood.

Once back in the studio, work began on the creation of a miniature mountain range, constructed from timber (reportedly a quarter-of-a-million feet), chicken wire, and burlap. Salt and flour were used in lieu of snow, and the resulting snowscape was surprisingly convincing on film. To film the Miner's hut teetering on the edge of the cliff, studio technicians created a miniature model and filmed the scene so smoothly that the cut from the full-size set to the model is hard to detect.

Victor Fleming's Wizard of Oz (1939) is a Technicolor triumph, but Dorothy's dream hid a nightmare special effect secret. Filming the poppy field scene on stage 29 at MGM's studio required planting 40,000 artificial flowers carefully placed into the floor of the set.

However, the real magic of the scene was the snow, sent by Glinda the Good Witch (Billie Burke) to break the spell placed on Dorothy (Judy Garland) and the Cowardly Lion (Bert Lahr) by the Wicked Witch of the West (Margaret Hamilton). But Glinda may have reconsidered if she knew exactly what she was sending - industrial grade chrysotile, otherwise known as the known cancer-causing substance asbestos, which the crew used as fake snow.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. A 1268/2, 1937-1938. Photo: Paramount. Claudette Colbert in I Met Him in Paris (Wesley Ruggles, 1937).

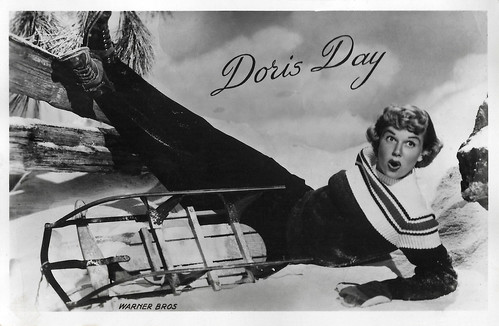

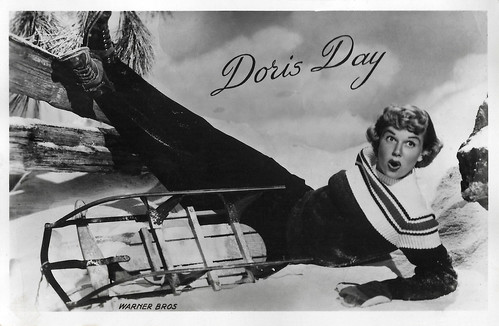

Doris Day. Dutch postcard by Takken, Utrecht, no. 287. Photo: Warner Bros.

Gina Lollobrigida. Dutch postcard by Uitgeverij Takken, Utrecht, no. 3207. Photo: Standaard Films.

Martha Hyer. Yugoslavian postcard by ZK, no. 2180.

Romy Schneider and Horst Buchholz. Dutch postcard by Uitg. Takken, Utrecht, no. 2077.

Shot in Encino, Calif., during a blistering summer, director Frank Capra's It's a Wonderful Life (1947) pioneered a new method for creating fake snow. Capra, working with Russel Sherman, RKO's head of special effects, developed a form of quiet snow specially for the film. Their new 'chemical snow' allowed actors to walk on it without creating the crunching sound typically associated with artificial snow of the time and also with real snow.

To make 'quiet' snow, foamite (used in fire extinguishers) was mixed with water, sugar, and soap flakes. The sprayable foam could then be applied to large areas quickly and efficiently, and could even be blown into the air with wind machines. To complete the effect, shaved ice was used to recreate slushy paths, and tons of plaster was sprayed on trees and used to create unmeltable snowbanks. In 1948, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences presented Russel Sherman and the RKO Radio Studio Special Effects Department with a Technical Award for their innovative efforts.

One of the scariest parts of Stanley Kubrick's horror classic The Shining (1980) is that the characters are snowed in at the Overlook Hotel, a desolate winter hideaway, which gives the viewers a sense of claustrophobia. This plays an important part near the end of the film when Jack Torrance (Jack Nicholson) is chasing his little son Danny (Danny Lloyd) through the hedge maze in the snow. For Kubrick and his crew it was obviously essential to use fake snow so that nobody became ill because of the temperatures and the crew pulled it off in an effective way. They made the snow from formaldehyde and salt.

The Living Daylights (John Glen, 1987) was the fifteenth film in the James Bond series. It was also the first of two films with Timothy Dalton as 007. Maryam d’Abo co-starred as his Bond's interest. One of our favourite scenes is the one following a crash and dramatic explosion. Bond escapes across the border the slopes of Bratislava, Slovakia, on a cello case that doubles as a sled. He ruins the costly instrument using to bat away bullets, but he makes up for it by whipping his love interest across the Austrian border to safety, holding up his passport and shouting "Nothing to declare!" as they scoot under the barrier.

The cello case was made of fibreglass, had skis on the bottom and control handles on the sides. Special Effects Supervisor John Richardson recalls: "As long as you made sure there was nothing at the bottom of the hill they were liable to crash into, it was actually quite fun to ride it down."

In John Cameron's Titanic (1997) a big hunk of Arctic sea ice is the big enemy. The iceberg easily punches through the Titanic’s super-chilled steel hull through five watertight compartments, allowing thousands of gallons of seawater to surge into the ship. Jack (Leonardo DiCaprio) and Rose (Kate Winslet) watch as the Iceberg grazes alongside the ship, sending small chunks of ice falling onto the decks.

Without a life jacket, Jack is caught in the suction of Titanic but he makes his way to the surface and reunites with Rose. They manage to swim to a floating door which seems to only be able to support one person's weight, so Rose climbs on top. As time passes many people die from the freezing water. Jack makes Rose promise him that she will never give up. However, the freezing cold water was not cold at all. “The water in the tank was about 80 degrees, so it was really like a pool,” James Cameron explained of the filming of the water scenes. “All of the cold, frigid water was added later.”

Sabine Sinjen. German postcard by UFA, Berlin-Tempelhoff, no. CK-316. Retail price: 30 Pfg. Photo: Arthur Grimm / UFA.

British postcard by World Postcards, no. X253, 1989. Photo: Albert Watson, 1981. Caption: Jack Nicholson, Snow.

French postcard by Danjaq A.S. / United Artists, 1987. Photo: Timothy Dalton and Maryam d'Abo in The Living Daylights (John Glen, 1987).

British postcard by Twentieth Century Fox / 7up, no. DD 2079A. Photo: Paramount / Fox. Leonardo DiCaprio and Kate Winslet in Titanic (James Cameron, 1997).

Dutch postcard by Film Freak Productions B.V., no. SP 04. Image: Comedy Central, 1999. Caption: Kick ass! South Park, Kyle.

Sources: Heidi Davis (Popular Mechanics), Kat Eschner (Smithsonian), Lilit Marcus (Mental Floss), The Telegraph, and M16.

French postcard by Croisant, Paris, no. 3664. Photo: Film Pathé. Publicity still for Le chemineau/The Tramp (Albert Capellani, 1905), based on the first part of Victor Hugo's novel 'Les misérables'. It's winter, snow falls on the desolate countryside. An exhausted tramp in vain asks for an alimony from passers-by. Unclear is who the actors are, but the sets were created by Hugues Laurent.

Swedish postcard by Nordisk Konst, Stockholm, no. 844/ 11. Photo: Svenska Biografteatern AB. Victor Sjöström in Berg-Ejvind och hans hustru/The Outlaw and His Wife (Victor Sjöström, 1918). Caption: Out to seek the lost.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 609/2. Photo: Messter-Film, Berlin. Henny Porten in the romantic comedy Ihr Sport/Her Sport (Rudolf Biebrach, 1919).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, Berlin, no. 760/6. Photo: Alex Binder. Pola Negri in Die Bergkatze/Wildcat (Ernst Lubitsch, 1921).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, Berlin, no. 677/2. Photo: Decla-Ufa-Film. Kriemhild (Margarete Schön) at the spring where Siegfried died in Die Nibelungen, II. Teil, Kriemhilds Rache/Kriemhild's Revenge (Fritz Lang, 1924).

French postcard by Hélio-Cachan. Photo: Charlie Chaplin in The Gold Rush (Charles Chaplin, 1925).

Asbestos as fake snow

The Swedish silent classic Berg-Ejvind och hans hustru/The Outlaw and His Wife (Victor Sjöström, 1918) is based on 'Fjalla-Eyvind' (1911), a play by the Icelandic playwright Jóhann Sigurjónsson. The film is set in Iceland, but was filmed in the North of Sweden, at Åre and Abisko, where fake snow was not needed. The film is not only a realist vision of the hardship of nature but also of the intolerance of humans. When the film came out, not only Sjöström's direction but also the cinematography of Julius Jaenzon was praised. French critic Louis Delluc called it the most beautiful film he saw until then, praising the director, the two leading actors and the landscape as 'third protagonist'.

In The Gold Rush (1925), Charles Chaplin found inspiration in the historical Klondike Gold Rush, and led him to drag the production's cast and crew to snowy, rustic Trukee, Nevada to serve as the scenic Chilkoot Pass in Alaska. Chaplin found directing his film difficult to control in the frigid conditions, and after coming down with the flu, he agreed to return to Hollywood.

Once back in the studio, work began on the creation of a miniature mountain range, constructed from timber (reportedly a quarter-of-a-million feet), chicken wire, and burlap. Salt and flour were used in lieu of snow, and the resulting snowscape was surprisingly convincing on film. To film the Miner's hut teetering on the edge of the cliff, studio technicians created a miniature model and filmed the scene so smoothly that the cut from the full-size set to the model is hard to detect.

Victor Fleming's Wizard of Oz (1939) is a Technicolor triumph, but Dorothy's dream hid a nightmare special effect secret. Filming the poppy field scene on stage 29 at MGM's studio required planting 40,000 artificial flowers carefully placed into the floor of the set.

However, the real magic of the scene was the snow, sent by Glinda the Good Witch (Billie Burke) to break the spell placed on Dorothy (Judy Garland) and the Cowardly Lion (Bert Lahr) by the Wicked Witch of the West (Margaret Hamilton). But Glinda may have reconsidered if she knew exactly what she was sending - industrial grade chrysotile, otherwise known as the known cancer-causing substance asbestos, which the crew used as fake snow.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. A 1268/2, 1937-1938. Photo: Paramount. Claudette Colbert in I Met Him in Paris (Wesley Ruggles, 1937).

Doris Day. Dutch postcard by Takken, Utrecht, no. 287. Photo: Warner Bros.

Gina Lollobrigida. Dutch postcard by Uitgeverij Takken, Utrecht, no. 3207. Photo: Standaard Films.

Martha Hyer. Yugoslavian postcard by ZK, no. 2180.

Romy Schneider and Horst Buchholz. Dutch postcard by Uitg. Takken, Utrecht, no. 2077.

Snow during a blistering summer

Shot in Encino, Calif., during a blistering summer, director Frank Capra's It's a Wonderful Life (1947) pioneered a new method for creating fake snow. Capra, working with Russel Sherman, RKO's head of special effects, developed a form of quiet snow specially for the film. Their new 'chemical snow' allowed actors to walk on it without creating the crunching sound typically associated with artificial snow of the time and also with real snow.

To make 'quiet' snow, foamite (used in fire extinguishers) was mixed with water, sugar, and soap flakes. The sprayable foam could then be applied to large areas quickly and efficiently, and could even be blown into the air with wind machines. To complete the effect, shaved ice was used to recreate slushy paths, and tons of plaster was sprayed on trees and used to create unmeltable snowbanks. In 1948, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences presented Russel Sherman and the RKO Radio Studio Special Effects Department with a Technical Award for their innovative efforts.

One of the scariest parts of Stanley Kubrick's horror classic The Shining (1980) is that the characters are snowed in at the Overlook Hotel, a desolate winter hideaway, which gives the viewers a sense of claustrophobia. This plays an important part near the end of the film when Jack Torrance (Jack Nicholson) is chasing his little son Danny (Danny Lloyd) through the hedge maze in the snow. For Kubrick and his crew it was obviously essential to use fake snow so that nobody became ill because of the temperatures and the crew pulled it off in an effective way. They made the snow from formaldehyde and salt.

The Living Daylights (John Glen, 1987) was the fifteenth film in the James Bond series. It was also the first of two films with Timothy Dalton as 007. Maryam d’Abo co-starred as his Bond's interest. One of our favourite scenes is the one following a crash and dramatic explosion. Bond escapes across the border the slopes of Bratislava, Slovakia, on a cello case that doubles as a sled. He ruins the costly instrument using to bat away bullets, but he makes up for it by whipping his love interest across the Austrian border to safety, holding up his passport and shouting "Nothing to declare!" as they scoot under the barrier.

The cello case was made of fibreglass, had skis on the bottom and control handles on the sides. Special Effects Supervisor John Richardson recalls: "As long as you made sure there was nothing at the bottom of the hill they were liable to crash into, it was actually quite fun to ride it down."

In John Cameron's Titanic (1997) a big hunk of Arctic sea ice is the big enemy. The iceberg easily punches through the Titanic’s super-chilled steel hull through five watertight compartments, allowing thousands of gallons of seawater to surge into the ship. Jack (Leonardo DiCaprio) and Rose (Kate Winslet) watch as the Iceberg grazes alongside the ship, sending small chunks of ice falling onto the decks.

Without a life jacket, Jack is caught in the suction of Titanic but he makes his way to the surface and reunites with Rose. They manage to swim to a floating door which seems to only be able to support one person's weight, so Rose climbs on top. As time passes many people die from the freezing water. Jack makes Rose promise him that she will never give up. However, the freezing cold water was not cold at all. “The water in the tank was about 80 degrees, so it was really like a pool,” James Cameron explained of the filming of the water scenes. “All of the cold, frigid water was added later.”

Sabine Sinjen. German postcard by UFA, Berlin-Tempelhoff, no. CK-316. Retail price: 30 Pfg. Photo: Arthur Grimm / UFA.

British postcard by World Postcards, no. X253, 1989. Photo: Albert Watson, 1981. Caption: Jack Nicholson, Snow.

French postcard by Danjaq A.S. / United Artists, 1987. Photo: Timothy Dalton and Maryam d'Abo in The Living Daylights (John Glen, 1987).

British postcard by Twentieth Century Fox / 7up, no. DD 2079A. Photo: Paramount / Fox. Leonardo DiCaprio and Kate Winslet in Titanic (James Cameron, 1997).

Dutch postcard by Film Freak Productions B.V., no. SP 04. Image: Comedy Central, 1999. Caption: Kick ass! South Park, Kyle.

Sources: Heidi Davis (Popular Mechanics), Kat Eschner (Smithsonian), Lilit Marcus (Mental Floss), The Telegraph, and M16.

No comments:

Post a Comment