The French silent film L'Occident/The West by Henri Fescourt premiered on 26 September 1928 at the Paris cinema Marivaux. The leading actors were Jaque Catelain, Claudia Victrix, and Lucien Dalsace. The film was part of a wave of French Orientalist films in the early 1920s. For the premiere at the Marivaux, Europe published a series of postcards, and the journal La Petite Illustration had a special issue with the same photos. We translated the photo captions and added them below in the card descriptions.

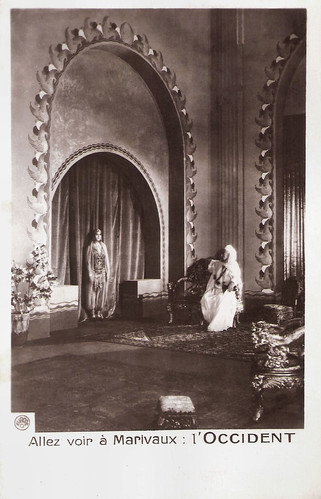

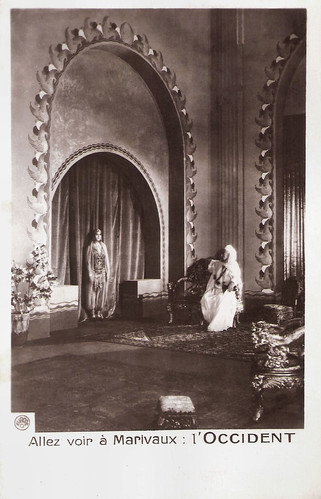

French postcard by Europe. Photo: still for L'Occident (Henri Fescourt, 1928). Europe. Caption: Hassina joins Taïeb in a deserted room.

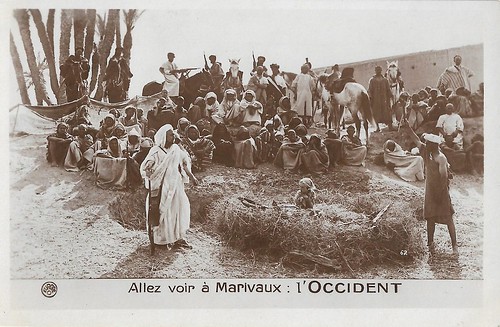

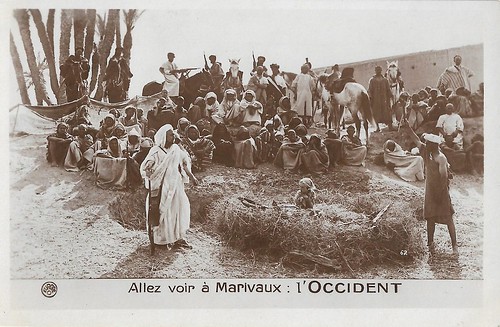

French postcard for L'Occident (Henri Fescourt, 1928). Photo: Cinema Europe. Caption: The Escape of the Looters. The left side of the card was printed out of focus.

L'Occident/The West was based on the play by Henri Kistemaeckers who also scripted the film. The film was produced by Société des Cinéromans, and distributed by Pathé Consortium Cinéma. The sets were designed by Robert Gys.

A French squadron before the coast of Morocco tries to prevent rebel gangs from attacking the caravans but is afraid to kill loyal citizens by bombing. So Captain Jean Cadière (Lucien Dalsace), who knows the local language and customs, is sent on a secret mission. He also substitutes for his young protégé, lieutenant Arnaud de Saint-Guil (Jaque Catelain).

The next morning, Hassina (Claudia Victrix), a captive of the tribe of Zerreth-Hama, finds Cadière at a well, bitten by a snake. Because of an old prediction, she believes he is her chosen one, so she saves him by sucking out his poison, considers him her master, and brings his papers to the French vessel. Arnaud is impressed by the mysterious woman.

The tribe leader, Taïeb (Hugues de Bagratide), discovers his stallion has been used and female traces are found, but only Hassina's little sister Fathima (Andrée Rolane) is discovered. When Taïeb threatens to burn Fathima if Hassina and Cadière don't come out, and his men attack the couple, the marine starts to fire its guns. The tribe flees, but Taïeb manages to kidnap Fathima.

The wounded Hassina is taken away, while the French soldiers lift their guns in homage. Hassina is taken to Toulon, deplores the loss of her sister, and understands her lover is a 'roumi', a French soldier. Cadière takes Hassani to the vast villa of his aunt Aline (Jane Méa), who adopts her, learns her French and music, but Hassani remains quiet and unhappy.

She has gotten a note that the roumi killed her sister, so she is torn between her family and her new lover. Instead, Fathima is not dead but also in Toulon, forced by Taïeb to dance every night in a den. When one night he treats her brutally, sailors, among whom Le Goff, an aid of Cadière, defend her. Meanwhile, Arnaud is troubled, not only because he is fed up with the army, but also because he is passionately in love with Hassina and hates Cadière.

At the betrothal party of Cadière and Hassani, Taïeb appears in disguise and pushes Hassani to avenge her sister, but her love is bigger than her desire for revenge. Arnaud leaves the army. Cadière's aid Le Goff finds Fathima and Taïeb, and after a struggle, the Moroccan confesses his crimes. Cadière himself prevents Arnaud of abducting Hassani and appeals to his conscience, so the latter returns to the army and abstains from committing a crime. Cadière also renders Hassani her sister, so that all ends well.

French postcard by Europe, no. 41. Photo: still for L'Occident (Henri Fescourt, 1928). Caption: Taïeb forces young Fathima to dance in a den in Toulon.

French postcard by Europe. Photo: still for L'Occident (Henri Fescourt, 1928). Caption: The hour of prayer of the tribe of Zerrath-Hama.

Cinémagazine wrote about the first night in Le Marivaux: "It was a great first. Marivaux welcomed Tout-Paris in a brand new room, with new painting and armchairs. They presented L'Occident [The West]. This film, the first part of which was set in Morocco, had to be Moroccan, it was not only by its images but also by the Nuba and the trumpets of the 6th and the 24th regiment of Spahis who, on the stage, let us hear the most ardent marches of their vibrant repertoire, which thrilled all those who were cavaliers of spahis ... even when, like me, they became territorial.

In the armchairs, on the balcony, in the boxes, the Tout-Paris: artists, people of the world, journalists and writers - shimmering toilets, tuxedos or black clothes. Mr. Painlevé, Minister of War, and General Carence seemed to encourage all the directors of the West. to show our soldiers the 'wheat' in action while in his chair, Mr. Steeg, resident general of France in Morocco, continuator and director, talked about the fruits of the efforts by Drude, Amade, and Lyautey. General Decoin, commanding the division of Spahis at Compiegne, could not find any criticism for the charge of spahis carried on the screen, while Charles Pathé, in the box of M. Sapene, applauded the Provence in action. In short, a beautiful room, a chic room - a room of a grand first night."

On the film itself, Cinémagazine wrote: " Mr. Henry Kistemaeckers has somewhat modified the script of his play, 'The West', created by Suzanne Desprez, which was already shot by Capellani with Nazimova. (...) The film ends with a wedding or an American kiss, which could have been frankly ridiculous, but the last image fades on words of forgiveness and sweetness, heavy with fatality and love, a prelude to other words. (...)

Claudia Victrix played Hassina. A heavy task to be true. This artist, rich in intelligent sensitivity, succeeded in conveying the conflict of the Moroccan primitive torn between her love for the roumi, her conqueror, and the atavism of her race. Towards her, Jaque Catelain, a young lieutenant, proves to be tender, while Lucien Dalsace plays a bitter, violent officer, fearless, and without reproach.

H. de Bagratide, a past master in the art of make-up, deserves a special mention for his composition of the role of Taïeb. Paul Guidé was able to command the battleship Provence with authority and Renée Veller, one of the winners of the last contest of Cinémagazine, as a painful fiancee shows us an upset face - which is beautiful. The little Andrée Rolane, already so appreciated, embodies gracefully the character of Fathima, the young sister of Hassina. Let's also quote Mrs. Jeanne Méa, MM. Liévin, Terrore, Labry, Raymond Guérin. But among the performers of the film, it would be unfair not to mention our sailors, our spahis, the Senegalese riflemen, and the men of the foreign legion who, in an admirably settled fight, jostled Taieb's looters.

The staging is by Henri Fescourt, a master to whom we owe the Miserables. It deserves to be praised. The fight, as we have said, is admirable of truth, but the director also knew how to use the constructions of the fleet, their guns pointing in the sky, of their life finally to make intensely a work where those of the hinterland play such a beautiful role. Finally, in the first part, there are Moroccan landscapes that recall the most beautiful shots of Les Miserables."

Richard Abel was in his book French Cinema: The First Wave, 1915-1929 quite critical of the colonial, stereotypical and Western ideology of the film, in which one of the questions is whether an Oriental woman can become a Western woman, while the lead is played by a Western actress (and Abel wasn't convinced of Victrix' play). Years after, director Fescourt himself recognised that none of the directors of the climactic battle scene - filmed in "the best western-style" as Abel writes - asked themselves at the time whether the local extras playing the retreating Moroccan crowds might have been unhappy with their roles.

Abel situates L'Occident within the wave of French Orientalist films after the success of L'Atlantide/Lost Atlantis (Jacques Feyder, 1921), with examples such as Visages voilés... âmes closes/The Sheik's Wife (Henry Roussel, 1921), Le Sang d'Allah/Passions of Araby (Luitz-Morat, Alfred Vercourt, 1922), Sables/Sand (Dimitri Kirsanoff, 1929), and Maman Colibri/Mother Hummingbird (Julien Duvivier, 1929). He also notes that it is remarkable that - possibly led by the negative public reactions to the war - French silent filmmakers hardly treated the war between the French foreign legion and the Moroccans, ending with the surrender of the Riftians in 1926.

French postcard by Europe, no. 62. Photo: still for L'Occident (Henri Fescourt, 1928). Caption:: The caïd Taïeb has decided to burn alive young Fathima.

Cover of the French journal La Petite Illustration, no. 398, 8 September 1928. It was a special issue on L'Occident (Henri Fescourt, 1928).

Sources: Cinémagazine, no 40, 5 October 1928, Fondation- Jerome Seydoux - Pathe, Richard Abel (French Cinema: The First Wave, 1915-1929), and IMDb.

French postcard by Europe. Photo: still for L'Occident (Henri Fescourt, 1928). Europe. Caption: Hassina joins Taïeb in a deserted room.

French postcard for L'Occident (Henri Fescourt, 1928). Photo: Cinema Europe. Caption: The Escape of the Looters. The left side of the card was printed out of focus.

Her love for a Roumi is bigger than her desire for revenge

L'Occident/The West was based on the play by Henri Kistemaeckers who also scripted the film. The film was produced by Société des Cinéromans, and distributed by Pathé Consortium Cinéma. The sets were designed by Robert Gys.

A French squadron before the coast of Morocco tries to prevent rebel gangs from attacking the caravans but is afraid to kill loyal citizens by bombing. So Captain Jean Cadière (Lucien Dalsace), who knows the local language and customs, is sent on a secret mission. He also substitutes for his young protégé, lieutenant Arnaud de Saint-Guil (Jaque Catelain).

The next morning, Hassina (Claudia Victrix), a captive of the tribe of Zerreth-Hama, finds Cadière at a well, bitten by a snake. Because of an old prediction, she believes he is her chosen one, so she saves him by sucking out his poison, considers him her master, and brings his papers to the French vessel. Arnaud is impressed by the mysterious woman.

The tribe leader, Taïeb (Hugues de Bagratide), discovers his stallion has been used and female traces are found, but only Hassina's little sister Fathima (Andrée Rolane) is discovered. When Taïeb threatens to burn Fathima if Hassina and Cadière don't come out, and his men attack the couple, the marine starts to fire its guns. The tribe flees, but Taïeb manages to kidnap Fathima.

The wounded Hassina is taken away, while the French soldiers lift their guns in homage. Hassina is taken to Toulon, deplores the loss of her sister, and understands her lover is a 'roumi', a French soldier. Cadière takes Hassani to the vast villa of his aunt Aline (Jane Méa), who adopts her, learns her French and music, but Hassani remains quiet and unhappy.

She has gotten a note that the roumi killed her sister, so she is torn between her family and her new lover. Instead, Fathima is not dead but also in Toulon, forced by Taïeb to dance every night in a den. When one night he treats her brutally, sailors, among whom Le Goff, an aid of Cadière, defend her. Meanwhile, Arnaud is troubled, not only because he is fed up with the army, but also because he is passionately in love with Hassina and hates Cadière.

At the betrothal party of Cadière and Hassani, Taïeb appears in disguise and pushes Hassani to avenge her sister, but her love is bigger than her desire for revenge. Arnaud leaves the army. Cadière's aid Le Goff finds Fathima and Taïeb, and after a struggle, the Moroccan confesses his crimes. Cadière himself prevents Arnaud of abducting Hassani and appeals to his conscience, so the latter returns to the army and abstains from committing a crime. Cadière also renders Hassani her sister, so that all ends well.

French postcard by Europe, no. 41. Photo: still for L'Occident (Henri Fescourt, 1928). Caption: Taïeb forces young Fathima to dance in a den in Toulon.

French postcard by Europe. Photo: still for L'Occident (Henri Fescourt, 1928). Caption: The hour of prayer of the tribe of Zerrath-Hama.

A wave of French Orientalist films

Cinémagazine wrote about the first night in Le Marivaux: "It was a great first. Marivaux welcomed Tout-Paris in a brand new room, with new painting and armchairs. They presented L'Occident [The West]. This film, the first part of which was set in Morocco, had to be Moroccan, it was not only by its images but also by the Nuba and the trumpets of the 6th and the 24th regiment of Spahis who, on the stage, let us hear the most ardent marches of their vibrant repertoire, which thrilled all those who were cavaliers of spahis ... even when, like me, they became territorial.

In the armchairs, on the balcony, in the boxes, the Tout-Paris: artists, people of the world, journalists and writers - shimmering toilets, tuxedos or black clothes. Mr. Painlevé, Minister of War, and General Carence seemed to encourage all the directors of the West. to show our soldiers the 'wheat' in action while in his chair, Mr. Steeg, resident general of France in Morocco, continuator and director, talked about the fruits of the efforts by Drude, Amade, and Lyautey. General Decoin, commanding the division of Spahis at Compiegne, could not find any criticism for the charge of spahis carried on the screen, while Charles Pathé, in the box of M. Sapene, applauded the Provence in action. In short, a beautiful room, a chic room - a room of a grand first night."

On the film itself, Cinémagazine wrote: " Mr. Henry Kistemaeckers has somewhat modified the script of his play, 'The West', created by Suzanne Desprez, which was already shot by Capellani with Nazimova. (...) The film ends with a wedding or an American kiss, which could have been frankly ridiculous, but the last image fades on words of forgiveness and sweetness, heavy with fatality and love, a prelude to other words. (...)

Claudia Victrix played Hassina. A heavy task to be true. This artist, rich in intelligent sensitivity, succeeded in conveying the conflict of the Moroccan primitive torn between her love for the roumi, her conqueror, and the atavism of her race. Towards her, Jaque Catelain, a young lieutenant, proves to be tender, while Lucien Dalsace plays a bitter, violent officer, fearless, and without reproach.

H. de Bagratide, a past master in the art of make-up, deserves a special mention for his composition of the role of Taïeb. Paul Guidé was able to command the battleship Provence with authority and Renée Veller, one of the winners of the last contest of Cinémagazine, as a painful fiancee shows us an upset face - which is beautiful. The little Andrée Rolane, already so appreciated, embodies gracefully the character of Fathima, the young sister of Hassina. Let's also quote Mrs. Jeanne Méa, MM. Liévin, Terrore, Labry, Raymond Guérin. But among the performers of the film, it would be unfair not to mention our sailors, our spahis, the Senegalese riflemen, and the men of the foreign legion who, in an admirably settled fight, jostled Taieb's looters.

The staging is by Henri Fescourt, a master to whom we owe the Miserables. It deserves to be praised. The fight, as we have said, is admirable of truth, but the director also knew how to use the constructions of the fleet, their guns pointing in the sky, of their life finally to make intensely a work where those of the hinterland play such a beautiful role. Finally, in the first part, there are Moroccan landscapes that recall the most beautiful shots of Les Miserables."

Richard Abel was in his book French Cinema: The First Wave, 1915-1929 quite critical of the colonial, stereotypical and Western ideology of the film, in which one of the questions is whether an Oriental woman can become a Western woman, while the lead is played by a Western actress (and Abel wasn't convinced of Victrix' play). Years after, director Fescourt himself recognised that none of the directors of the climactic battle scene - filmed in "the best western-style" as Abel writes - asked themselves at the time whether the local extras playing the retreating Moroccan crowds might have been unhappy with their roles.

Abel situates L'Occident within the wave of French Orientalist films after the success of L'Atlantide/Lost Atlantis (Jacques Feyder, 1921), with examples such as Visages voilés... âmes closes/The Sheik's Wife (Henry Roussel, 1921), Le Sang d'Allah/Passions of Araby (Luitz-Morat, Alfred Vercourt, 1922), Sables/Sand (Dimitri Kirsanoff, 1929), and Maman Colibri/Mother Hummingbird (Julien Duvivier, 1929). He also notes that it is remarkable that - possibly led by the negative public reactions to the war - French silent filmmakers hardly treated the war between the French foreign legion and the Moroccans, ending with the surrender of the Riftians in 1926.

French postcard by Europe, no. 62. Photo: still for L'Occident (Henri Fescourt, 1928). Caption:: The caïd Taïeb has decided to burn alive young Fathima.

Cover of the French journal La Petite Illustration, no. 398, 8 September 1928. It was a special issue on L'Occident (Henri Fescourt, 1928).

Sources: Cinémagazine, no 40, 5 October 1928, Fondation- Jerome Seydoux - Pathe, Richard Abel (French Cinema: The First Wave, 1915-1929), and IMDb.

No comments:

Post a Comment