French postcard, probably issued by Vitagraph's subsidiary in Paris, no. 3. Photo: Vitagraph.

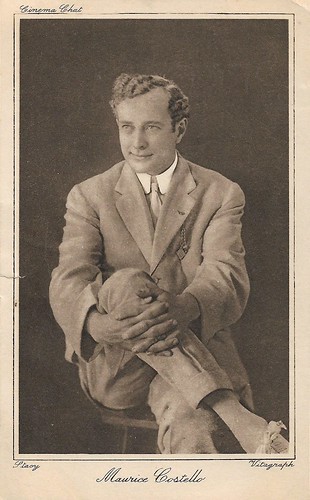

British Postcard by Cinema Chat. Photo: Stacy.

The father of screen acting

Maurice George Costello was born in 1877 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania to Irish immigrants Ellen (née Fitzgerald) and Thomas Costello. His father Thomas died while repairing a blast furnace at Andrew Carnegie's Union Iron Mill when Maurice was just five months old. He had a strongly Irish upbringing, living with his mother, her Irish brother, and many Irish immigrant boarders. After various jobs as messenger, office boy, and the like, Costello made his stage debut in local Pittsburgh vaudeville in 1894 singing Irish songs like 'Here Lies the Mick That Threw the Brick (He'll Never Throw Another).' Finding some success in the theatre, he toured on stage in 'Scotland Yard', 'The Kentucky Feud', and 'The Cowboy and the Lady'. While appearing in the latter play he married Mae Altshuk in 1902. It would prove to be a stormy union.

Though some sources claim he started at Edison in 1905, most sources agree that Costello made his film debut in 1908 at the company Vitagraph. At first, he specialised in Shakespearean roles, and in his first year, he starred in adaptations of Richard III (J. Stuart Blackton, William V. Ranous, 1908), Antony and Cleopatra (J. Stuart Blackton, Charles Kent, 1908), Julius Caesar (J. Stuart Blackton, William V. Ranous, 1908), The Merchant of Venice (J. Stuart Blackton, 1908), King Lear (J. Stuart Blackton, William V. Ranous, 1909), and A Midsummer Night's Dream (Charles Kent, J. Stuart Blackton, 1909).

He then broadened his range to take in contemporary melodrama and sophisticated comedy. Nicknamed "Dimples" by his colleagues, Costello was adored by early filmgoers. Quickly he became one of its leading men players, opposite actresses such as Florence Turner, and later on Clara Kimball Young, Norma Talmadge, and Lilian Walker. Among his male co-actors were William V. Ranous, Leo Delaney, Charles Eldridge, Tom Powers, and Van Dyke Brooke. He won the cinema's first-ever popularity poll, conducted by Motion Picture Story magazine in 1912, with more than 400,000 votes cast in his favour, but the results are rather suspect, however, since the magazine was owned by Vitagraph.

Costello was notorious for his refusal to help build sets, insisting that he was "hired as an actor and nothing else", despite the common practice of the time. However, Costello proved to be a popular player and he was among the first actors to receive on-screen credit beginning in 1911. From this and his role as the creator of the first known school of screen acting, Costello is sometimes credited as "the father of screen acting". In 1909, Costello discovered Moe Howard of the Three Stooges, who, as a teenager, ran errands and got lunches for the actors at the Vitagraph Studios at no charge. This impressed Costello who brought him in and introduced him to other leading actors of the day. Moe then gained small parts in many of the Vitagraph movies, under the name Harry Howard. Most of these were destroyed by a fire that swept the studios in 1910.

On the Desmet Playlist of the Dutch EYE Filmmuseum, you can find several of Costello's shorts for Vitagraph, such as Lulu's Doctor (1912) also with little Dolores Costello, The Picture Idol (1912), It All Came Out in the Wash (1912), When Persistency and Obstinacy Meet (1912), A Vitagraph Romance (1912), Mrs. 'Enry 'Awkins (1912), The Days of Terror (1912), Aunty's Romance (1912), The Meeting of the Ways (1912), also with Dolores and Helene Costello, The Lonely Princess (1913) shot in Venice, Italy, and Delayed Proposals (1913). Some are in tinted versions. With Mae Costello (née Altschuk), he had two daughters, Dolores (born in 1905), and Helene (born in 1903) would, as children, act in his films. On 23 November 1913, Costello was arrested for beating his wife. Costello admitted that he had beaten his wife while intoxicated. Mae Costello requested that the charges be dropped to disorderly conduct, and Costello was given six months probation by Magistrate Geisner of the Coney Island Police Court. Costello's domestic troubles wreaked havoc with his public approval.

British postcard in the Novelty Series, no. D6-9. Photo: Vitagraph Films.

British postcard, editor unknown. Caption: Maurice Costello, of the Vitagraph Players.

Playing second fiddle and finally bit parts

With Robert Gaillard, Maurice Costello co-directed many films at Vitagraph, as of 1910, both shorts and features. Among some of his best-known pictures are Les Miserables (3 parts, 1909), A Tale of Two Cities (William Humphrey, 1911), For Love and Glory (Van Dyke Brooke, 1911), The Golden Pathway (1913), and Iron and Steel (Maurice Costello, Robert Gaillard, 1914).

The Man Who Couldn't Beat God (Maurice Costello, Robert Gaillard, 1915) was Costello's last film direction. He suffered a nervous breakdown and was absent from the screen for a year. When he returned, he seemed suddenly aged. He starred in the Erbograph-Consolidated serial The Crimson Stain Mystery (1916), but the bad publicity had already done its damage. Costello and his wife reconciled for a time. After another absence between 1916 and 1919, Costello returned to the screen and to Vitagraph, but now only as an actor, opposite actresses such as Corinne Griffith.

His last film for Vitagraph was probably The Tower of Jewels (Tom Terriss, 1920). In the 1920s Costello worked for various small production companies but also several times for Paramount, often playing second fiddle to the male and female star, e.g. as Armand's father in Fred Niblo's Camille (1926), starring Norma Talmadge and Gilbert Roland. He continued to act in the silent film until 1928. In 1925 he attempted a comeback in vaudeville with a dramatic sketch called 'The Battle'. The act opened in Staten Island, but it stirred little interest. In 1928 he tried another dramatic sketch, 'The Pay Off'. This opened in Tacoma, Washington, and again did nothing to revive his career.

In 1927, he and Mae divorced. He was strongly opposed to the marriage of daughter Dolores Costello to John Barrymore. Maurice knew of Barrymore's history of womanising and heavy drinking and was strongly put off by the fact that Barrymore was closer in age to him than his daughter, and he frequently begged his daughter not to go through with it, saying that it would not last. She went against his wishes and married Barrymore anyway. Like a lot of other silent screen stars, Costello had found the transition to 'talkies' extremely difficult, and his leading man status was over when sound set in. Between 1928 and 1934 Maurice Costello was away from the film sets. Apart from incidental bit parts in the mid-1930s, he did a whole range of uncredited parts in American films since then. Costello suffered a cerebral haemorrhage in 1932 while eating in a Beverly Hills drug store, but the stroke was minor and he recovered fully. He came out of retirement to take a small role in Hollywood Boulevard (Robert Florey, 1936) and also did some radio work.

By the late 1930s, his career had declined to the point where he was reduced to taking unbilled work as a background extra for a day or two at a few dollars a day. By 1939 he was so broke that he had to sue his daughters for financial support. In 1939, he married thirty-year-old Ruth Reeves, an operator at the Central Casting Agency. Robert S. Birchard at Hollywood Heritage: "In 1941 the second Mrs. Costello sought a Tijuana divorce claiming that Costello was "unreasonably and insanely jealous" and that he threatened her with a .22 rifle." From 1946 to the end of his life Maurice Costello lived in retirement as a resident of the Motion Picture Country House in Los Angeles. In 1950 Costello died at the age of 73 there, due to a heart problem. His descendants include two daughters, actresses Dolores Costello and Helene Costello, a grandson, actor John Drew Barrymore, and a great-granddaughter, film actress Drew Barrymore.

Spanish postcard by PH.

American postcard by Kraus Mfg. Co., New York. Photo: Vitagraph.

American postcard by Kraus Mfg. Co., New York. Photo: Vitagraph Players.

American postcard by Vitagraph Co., no. 39.

Sources: Robert S. Birchard (Hollywood Heritage - WaybackMachine), Bobb Edwards (Find A Grave), Wikipedia, and IMDb.

This post was last updated on 30 October 2023.

No comments:

Post a Comment