Jean Toulout (1887-1962) was a French stage and screen actor, director and scriptwriter. He appeared in more than 100 films between 1911 and 1959. Toulout was married to the actress Yvette Andréyor between 1917 and 1926.

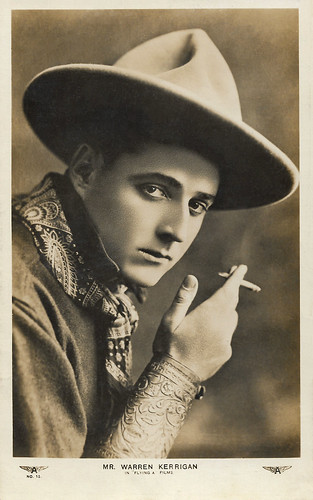

French postcard by A.N., Paris, no.566. Photo: G.F.F.A. (Gaumont-Franco-Film-Aubert), a company existing between 1930 and 1938.

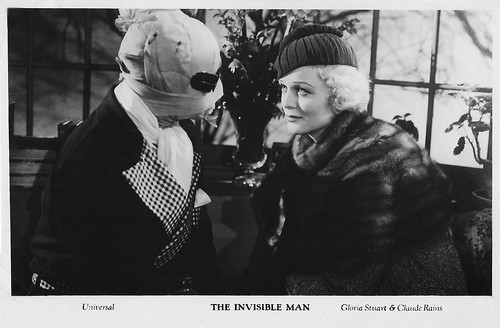

French collector card by Les Fiches de Monsieur Cinéma. Still from

Les Misérables (Henri Fescourt, 1925), with

Gabriel Gabrio as Jean Valjean/ M. Madeleine,

Jean Toulout as Javert and

Sandra Milowanoff as Fantine.

An intense early film career

Jean Joseph Charles Toulout was born in Paris in 1887. He was the son of

Dominique Georges Toulout and

Charlotte Louise Isabelle Monginot. While no real online biography has been written about him, this bio is largely based on Toulout’s filmography. According to

Wikipedia, Toulout started to act on stage at least from 1907, when he played in the

Victor Hugo play 'Marion Delorme' at the Comédie Française. One year later, he was already acting at the Théàtre des Arts, so if he ever was a member of the Comédie Française, then not for long. In 1911, he travelled around with

Firmin Gémier’s wandering stage company, while at least from 1913, he settled in Paris playing with

André Antoine’s 1913 staging of

Paul Lindau’s 'The Prosecutor Hallers'.

At the same time,

Jean Toulout debuted in French film. His career in the cinema would quickly become much more intense than his stage career. All in all, he would act in some 100 films within four decades. Toulout started in short films for

Abel Gance’s company Le film français. He appeared in Gance's debut film,

La Digue / The Dyke (Abel Gance, 1912), which was never released. That year followed

Il y a des pieds au plafond / There are feet on the ceiling.,

Le Nègre blan / The White Negro, and

Le Masque d’horreur / The Mask of Horror starring

Édouard de Max, all directed by

Abel Gance in 1912. Soon, Toulout had various parts at Gaumont, Pathé and smaller companies.

His early films included

Louis Feuillade's

La Maison des lions / The Lion Menagerie (1912),

L’Homme qui assassina / The man who murdered (Henri Andréani, 1913),

Jacques l’honneur / Jacques the Honourable (Henri Andréani, 1913) and

Les Enfants d'Édouard / The Crown of Richard III (Henri Andréani, 1914), inspired by

William Shakespeare's 'Richard III'. In

L’Homme qui assassina / The Man Who Murdered (Henri Andréani, 1913), he is the evil, adulterous Lord Falkland. He presses his equally adulterous but goodhearted wife (

Mlle Michelle) to either say goodbye to her child or publicly confess her sin. Her lover (

Firmin Gémier) kills the husband, but is acquitted by the local Turkish commissioner (

Adolphe Candé), who is understanding in these matters. Toulout also appeared in films directed by

Gaston Leprieur,

René Leprince,

Gérard Bourgeois and

Alexandre Devarennes. He didn’t act on screen in 1915, possibly because he was involved in the military during the First World War.

From late 1916, he was back on track in several Gaumont films by Feuillade and others. In Feuillade’s

L’Autre / The Other (Louis Feuillade, 1917), he met the actress

Yvette Andréyor, famous for her parts in Feuillade’s serials

Fantomas (1913) and

Judex (1916). Toulout and Andréyor married on 12 June 1917 and would perform together in various films until their divorce in 1926. In 1918, Toulout was the evil antagonist of

Emmy Lynn in Gance’s

La Dixième Symphonie / The Tenth Symphony (Abel Gance, 1918), blackmailing her for having accidentally killed his sister. He thus risks wrecking her new marriage with a composer (

Séverin-Mars) but also the life of the composer’s daughter (

Elizabeth Nizan). Luckily for the other, he doesn’t kill them, only himself. As English

Wikipedia writes, “Gance's mastery of lighting, composition and editing was accompanied by a range of literary and artistic references which some critics found pretentious and alienating.”

While Toulout would be reunited with

Emmy Lynn in

La faute d’Odette Marchal (Henri Roussel, 1920), he would also be reunited with

Séverin-Mars as – again – a jealous, evil husband in

Jacques Landauze (André Hugon, 1920). With director Hugon, Toulout would do several films in the 1920s and 1930s:

Le Roi de Camargue / King of the Camargue (André Hugon, 1921),

Notre Dame d'amour / Our Lady of Love (André Hugon, 1922),

Le Diamant noir / The Black Diamond (André Hugon, 1922),

La Rue du pavé d'amour / Love Pavement Street (André Hugon, 1923), and the first French sound film,

Les Trois masques / The Three Masks (André Hugon, 1929), shot at the London Elstree studios in 15 days.

French film journal

Mon Ciné, no. 44, 21 December 1922 (Cover).

Jean Toulout in

La Conquête des Gaules / The Conquest of Gaul (Marcel Yonnet, Yan Bernard Dyl, Léonce-Henri Burel, 1922). In the film, a film director, Jean Fortier, tries with scarce means to film Julius Caesar's 'The Conquest of Gaul'. The film was shot at the Gaumont studios.

French film journal

La Petite Illustration, no. 345, 13 August 1927, p. 8.

Jean Toulout as General Prince Tcherkoff and

Claudia Victrix as Princess Masha in

La princesse Masha / Princess Masha (René Leprince, 1927).

Again, a jealous husband who threatens to kill his wife

Jean Toulout also acted in films by

Pierre Bressol (

Le Mystère de la villa Mortain / The Mystery of Villa Mortain (1919) and

La Mission du docteur Klivers / The Mission of Doctor Klivers (1919)),

Germaine Dulac (

La fète espagnole / The Spanish Celebration (1920) and

La belle dame sans-merci / The Beautiful Woman Without Mercy (1921)),

Jacques Robert,

Henri Fescourt,

Armand du Plessis, and others. In

La belle dame sans-merci, he is a local count who understands that the playful femme fatale he brought home is wrecking his whole family, so he has them reunited. In

Chantelouve (Georges Monca, 1921), he was once more the jealous husband who threatens to kill his wife (

Yvette Andréyor). In

La conquête des Gaules / The Conquest of Gaul (Yan B. Dyl, Marcel Yonnet, 1923), he is a film director who tries to film the conquest of the Gauls with modest means. In

Le Crime de Monique (Robert Péguy, 1923),

Yvette Andréyor is accused of killing her brutal, violent husband (Toulout, of course).

Jean Toulout also acted in

Abel Gance’s hilarious comedy

Au secours! / The Haunted House (1924), starring

Max Linder as a man who takes a bet to stay a night in a haunted house. Toulout masterfully performed the persistent commissionary Javert in

Les Misérables (Henri Fescourt, 1925), opposite

Gabriel Gabrio as Jean Valjean. When a restored version was shown at the Giornate del Cinema Muto in Pordenone in October 2015,

Peter Walsh wrote on his blog

Burnt Retina: "

Gabriel Gabrio as Jean Valjean was a towering presence on screen, and his redemptive arc and gradual ageing were shown convincingly.

Jean Toulout as Javert was also superb, at times overpowered by some of the mightiest brows and mutton chops I’ve seen in a long time. The climax of his personal crisis, and collapse of his moral world, was incredibly striking, with extreme close-ups capturing a bristling performance."

After smaller parts as in

Germaine Dulac’s

Antoinette Sabrier (1927), in which Toulout would be paired with Gabrio again, Toulout left the set in 1928 and instead returned to the stage for 'Le Carnaval de l'amour' at the Théâtre de la Porte-Saint-Martin. In 1929, however, Toulout returned as Mr de Villefort in the late silent film

Monte Christo / The Count of Monte-Cristo (Henri Fescourt, 1929) – the last big silent French production - as well as in the first French sound film

Les Trois masques / The Three Masks (André Hugon, 1929) as a Corsican whose son (

François Rozet) makes a girl (

Renée Héribel) pregnant, after which her brothers take revenge during the carnival. Toulout had the lead in the Henry Bataille adaptation

La Tendresse / Tenderness (André Hugon, 1930) as a famous, older academician who discovers his much younger wife (

Marcelle Chantal) isn’t that much in love with him as he is with her. When he gravely falls ill, he discovers she still gave the best of her life to him.

Toulout tried his luck in film direction and with

Joe Francis, he directed

Le Tampon du Capiston / The Capiston Stamp (1930), a comical operetta film on an old spinster (

Hélène Hallier), a captain’s sister, who wants to marry the captain’s aide (

Rellys), who presumably has inherited a fortune. In the same year, Toulout also wrote the scripts for two other films, both by Hugon:

La Femme et le Rossignol / Nightingale Girl (André Hugon, 1930) and

Lévy & Cie / Levy and Company (André Hugon, 1930). The collaboration continued in 1931 when Toulout scripted and starred in

Le Marchand de sable / The Sandman (André Hugon, 1930), while he had a supporting part in

La Croix du Sud / Southern Cross (André Hugon, 1930). The collaboration with Hugon would last till well into the mid-1940s with

Le Faiseur / Mercadet (André Hugon, 1936),

Monsieur Bégonia (André Hugon, 1937),

La Rue sans joie / Street Without Joy (André Hugon, 1938),

Le Héros de la Marne / Heroes of the Marne (André Hugon, 1938),

La Sévillane / The Woman from Seville (André Hugon, 1943), and

Le Chant de l'exilé / The Exile's Song (André Hugon, 1943). In 1931, Toulout also scripted

Moritz macht sein Glück / Moritz Makes his Fortune, a German film by Dutch director

Jaap Speijer. All through the 1930s, Toulout had a steady, intense career as an actor, but in 1934, he also directed his second film,

La Reine du Biarritz / The Queen of Biarritz, in which he himself had only a small part. Elenita de Sierra Mirador (

Alice Field) is the toast of Biarritz. For her, a young groom leaves his wife. For her, a forty-year-old man suddenly deceives his young wife. But Elenita, watched by her mother, resigns herself to becoming honest and returns to her husband.

Jean Toulout had mostly supporting parts, as in

Le petit roi / The Little King (Julien Duvivier, 1933),

Fédora (Louis Gasnier, 1934) starring

Marie Bell,

Les Nuits moscovites / Moscow Nights (Alexis Granowsky, 1934), and

L'Épervier / The Hawk (Marcel L’Herbier, 1934). He could act the jealous, shooting husband again in

Le Vertige / Vertigo (Paul Schiller, 1935), again starring

Alice Field. He was the judge who forced

Henri Garat and

Lilian Harvey to marry on the spot in

Les Gais Lurons / Lucky Kids (Jacques Natanson, Paul Martin), the French version of Martin’s

Glückskinder. He is the prosecutor in

La Danseuse rouge / The Red Dancer (Jean-Paul Paulin, 1937), a court case drama starring

Vera Korène and inspired by

Mata Hari’s trial. Toulout continued to act in minor film parts in the late 1930s, during the war years and the late 1940s: fathers, judges, doctors, officers, aristocrats. But a major part among the first three actors of the film he didn’t have anymore. Memorable were his parts in

Édouard et Caroline / Edward and Caroline (Jacques Becker, 1951), starring

Daniel Gélin and

Anne Vernon, and – again as a judge - in

Obsession (Jean Delannoy, 1952) with

Michèle Morgan and

Raf Vallone. Toulout also worked as a voice actor in France, playing

Donald Crisp’s part in

How Green Was My Valley (John Ford, 1941, released in France in 1946), and

Nigel Bruce’s part in

Limelight (Charles Chaplin, 1952). In the late 1950s, he also acted on television.

Jean Toulout died in l'hôpital de Ambroise Paré in Paris in 1962. He was 75. He is buried in the cemetery of Saint-Cloud, Hauts-de-Seine. His second wife was

Simone Berthe Henriette Chéron.

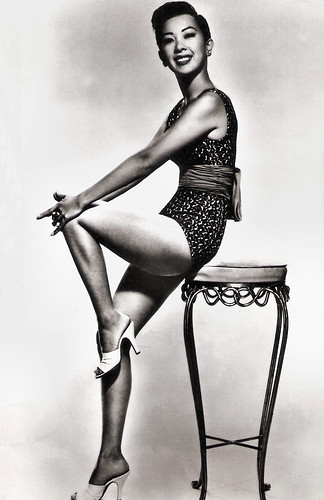

French postcard in the series Nos artistes dans leur loge, no. 325. Photo: Comoedia.

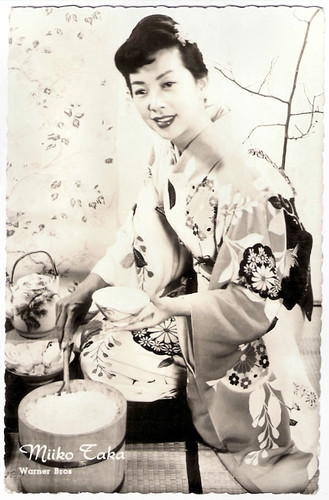

French postcard by Editions-Cinémagazine.

French postcard in the Les Vedettes du Cinéma series by Editions Filma, no. 28. Photo: Agence Générale Cinématographique.

Sources:

Peter Walsh,

Les Gens du Cinéma (French),

DVD-toile (French), Wikipedia (

English,

French and

Italian) and

IMDb.