Austrian postcard by Iris-Verlag, no. 5853. Photo: British International Pictures (BIP). Anna May Wong in Piccadilly (Ewald André Dupont, 1929).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 5028/2, 1930-1931. Photo: Atelier Manassé, Wien (Vienna).

A U.S. coin featuring Anna May Wong, 2022.

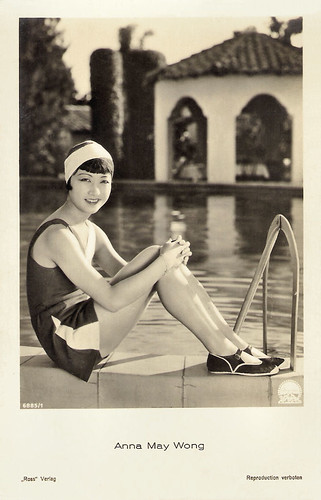

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 6677/1, 1931-1932. Photo: Paramount. Anna May Wong in Shanghai Express (Josef von Sternberg, 1932).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 6679/1, 1931-1932. Photo: Paramount. Anna May Wong and Clive Brook in Shanghai Express (Josef von Sternberg, 1932).

Vibrant, erotic star quality

Anna May Wong (Chinese: 黃柳霜; pinyin: Huáng Liǔshuāng) was born Wong Liu Tsong (Frosted Yellow Willows) near the Chinatown neighbourhood of Los Angeles in 1905. She was the second of seven children born to Wong Sam Sing, owner of the Sam Kee Laundry in Los Angeles, and his second wife Lee Gon Toy. Wong had a passion for movies. By the age of 11, she had come up with her stage name Anna May Wong, formed by joining both her English and family names.

Wong was working at Hollywood's Ville de Paris department store when Metro Pictures needed 300 girl extras to appear in The Red Lantern (Albert Capellani, 1919) starring Nazimova as a Eurasian woman who falls in love with an American missionary. The film included scenes shot in Chinatown. Without her father's knowledge, a friend of his with movie connections helped Anna May land an uncredited role as an extra carrying a lantern. In 1921 she dropped out of Los Angeles High School to pursue a full-time acting career. Wong received her first screen credit for Bits of Life (Marshall Neilan, 1921), the first anthology film, in which she played the abused wife of Lon Chaney, playing a Chinaman.

At 17, she played her first leading part, Lotus Flower, in The Toll of the Sea (Chester M. Franklin, 1922), the first Technicolor production. The story by Hollywood's most famous scenarist at the time, Frances Marion, was loosely based on the opera Madame Butterfly but moved the action from Japan to China. Wong also played a concubine in Drifting (Tod Browning, 1923) and a scheming but eye-catching Mongol slave girl running around with Douglas Fairbanks Jr in the super-production The Thief of Bagdad (Raoul Walsh, 1924).

Richard Corliss in Time: “Wong is a luminous presence, fanning her arms in right-angle gestures that seem both Oriental and flapperish. Her best scenes are with Fairbanks, as they connive against each other and radiate contrasting and combined sexiness — a vibrant, erotic star quality.” Wong began cultivating a flapper image and became a fashion icon. In Peter Pan (Herbert Brenon, 1924), shot by her cousin cinematographer James Wong Howe, she played Princess Tiger Lily who shares a long kiss with Betty Bronson as Peter. Peter Pan was the hit of the Christmas season. She appeared again with Lon Chaney in Mr. Wu (William Nigh, 1927) at MGM and with Warner Oland and Dolores Costello in Old San Francisco (Alan Crosland, 1927) at Warner Brothers.

Wong starred in The Silk Bouquet/The Dragon Horse (Harry Revier, 1927), one of the first US films to be produced with Chinese backing, provided by San Francisco's Chinese Six Companies. The story was set in China during the Ming Dynasty and featured Asian actors playing Asian roles. Hollywood studios didn't know what to do with Wong. Her ethnicity prevented US filmmakers from seeing her as a leading lady. Frustrated by the stereotypical supporting roles as the naïve and self-sacrificing ‘Butterfly’ and the evil ‘Dragon Lady’, Anna May Wong left for Europe in 1928.

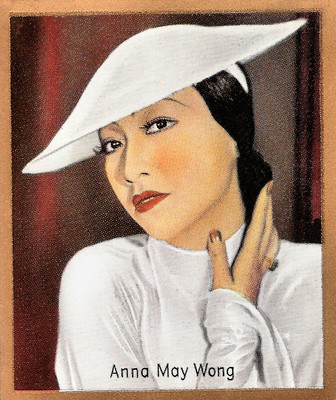

German cigarette card in the series Unsere Bunten Filmbilder by Ross Verlag for Cigarettenfabrik Josetti, Berlin, no. 187. Photo: Paramount.

British postcard in the Picturegoer series. Photo: Dorothy Wilding.

British postcard in the Colourgraph Series, London, no. C 7.

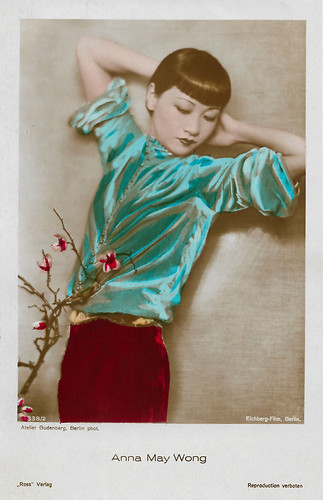

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 4338/2, 1929-1930. Photo: Atelier Gudenberg, Berlin / Eichberg-Film, Berlin. Collection: Geoffrey Donaldson Institute.

A Sensation In Europe

In Germany, Anna May Wong became a sensation in Schmutziges Geld/Show Life (Richard Eichberg, 1928) with Heinrich George. The New York Times reported that Wong was "acclaimed not only as an actress of transcendent talent but as a great beauty (...) Berlin critics, who were unanimous in praise of both the star and the production, neglect to mention that Anna May is of American birth. They mention only her Chinese origins."

Other film parts were a circus artist on the run from a murder charge in Großstadtschmetterling/City Butterfly (Richard Eichberg, 1929), and a dancer in pre-Revolutionary Russia in Hai-Tang (Richard Eichberg, Jean Kemm, 1930). In Vienna, she played the title role in the stage operetta 'Tschun Tschi' in fluent German. Wong became an inseparable friend of director Leni Riefenstahl. According to Wikipedia, her close friendships with several women throughout her life, including Marlene Dietrich, led to rumours of lesbianism which damaged her public reputation.

London producer Basil Dean bought the play 'A Circle of Chalk' for Wong to appear in with the young Laurence Olivier, her first stage performance in the UK. Her final silent film, Piccadilly (Ewald André Dupont, 1929), caused a sensation in the UK. Gilda Gray was the top-billed actress, but Variety commented that Wong "outshines the star", and that "from the moment Miss Wong dances in the kitchen's rear, she steals Piccadilly from Miss Gray."

It would be the first of five English films in which she had a starring role, including her first sound film The Flame of Love (Richard Eichberg, Walter Summers, 1930). American studios were looking for fresh European talent. Ironically, Wong caught their eye and she was offered a contract with Paramount Studios in 1930.

She was featured in Daughter of the Dragon (Lloyd Corrigan, 1931) as the vengeful daughter of Fu Manchu (Warner Oland), and with Marlene Dietrich in Shanghai Express (Josef von Sternberg, 1932). Wong spent the first half of the 1930s travelling between the United States and Europe for film and stage work. She repeatedly turned to the stage and cabaret for a creative outlet. On Broadway, she starred in the drama 'On the Spot', which ran for 167 performances and which she would later film as Dangerous to Know (Robert Florey, 1938).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 5028/1, 1930-1931. Photo: Manassé, Wien.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 5167/1, 1930-1931. Photo: Atelier Gudenberg, Berlin.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 5477/1, 1930-1931. Photo: Atelier Manassé, Wien (Vienna).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 5568/1, 1930-1931. Photo: Frhr. v. Gudenberg, Berlin.

Too Chinese to play a Chinese

Anna May Wong became more outspoken in her advocacy for Chinese American causes and for better film roles. Because of the Hays Code's anti-miscegenation rules, she was passed over for the leading female role in The Son-Daughter (Clarence Brown, 1932) in favour of Helen Hayes. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer deemed her ‘too Chinese to play a Chinese’ in the film, and the Hays Office would not have allowed her to perform romantic scenes since the film's male lead, Ramón Novarro, was not Asian.

Wong was scheduled to play the role of a mistress to a corrupt Chinese general in The Bitter Tea of General Yen (Frank Capra, 1933), but the role went instead to Toshia Mori. Her British film Java Head (Thorold Dickinson, J. Walter Ruben, 1934) was the only film in which Wong kissed the lead male character, her white husband in the film.

In 1935 she was dealt the most severe disappointment of her career when Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer refused to consider her for the leading role of the Chinese character O-Lan in the film version of Pearl S. Buck's The Good Earth (Sidney Franklin, 1937). Paul Muni, an actor of European descent, was to play O-lan's husband, Wang Lung, and MGM chose German actress Luise Rainer for the leading role. Rainer won the Best Actress Oscar for her performance.

Wong spent the next year touring China, visiting her father and her younger brothers and sister in her family's ancestral village Taishan and studying Chinese culture. To complete her contract with Paramount Pictures, she starred in several B movies, including Daughter of Shanghai (Robert Florey, 1937), Dangerous to Know (Robert Florey, 1938), and King of Chinatown (Nick Grinde, 1939) with Akim Tamiroff. These smaller-budgeted films could be bolder than the higher-profile releases, and Wong used this to her advantage to portray successful, professional, Chinese-American characters.

Wong's cabaret act, which included songs in Cantonese, French, English, German, Danish, Swedish, and other languages, took her from the US to Europe and Australia through the 1930s and 1940s. She paid less attention to her film career during World War II but devoted her time and money to helping the Chinese cause against Japan. Wong starred in Lady from Chungking (William Nigh, 1942) and Bombs over Burma (Joseph H. Lewis, 1943), both anti-Japanese propaganda made by the poverty row studio Producers Releasing Corporation. She donated her salary for both films to United China Relief. She invested in real estate and owned several properties in Hollywood.

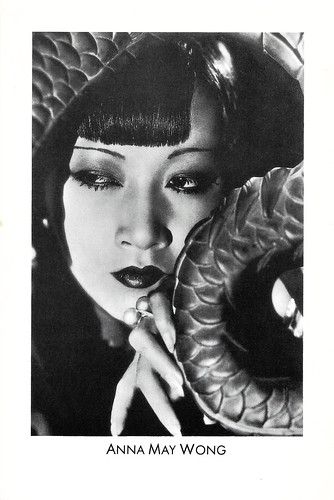

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 6082/1, 1931-1932. Photo: Paramount. Anna May Wong in Daughter of the Dragon (Lloyd Corrigan, 1931).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 6084/2, 1931-1932. Photo: Paramount. Sessue Hayakawa and Anna May Wong in Daughter of the Dragon (Lloyd Corrigan, 1931).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 6403/1, 1931-1932. Photo: Paramount. Sessue Hayakawa and Anna May Wong in Daughter of the Dragon (Lloyd Corrigan, 1931).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 6887/1, 1931-1932. Photo: Paramount.

Rumoured Mistress Of Several Prominent Film Men

Anna May Wong returned to the public eye in the 1950s in several television appearances as well as her own detective series The Gallery of Madame Liu-Tsong (1951-1952), the first US television show starring an Asian-American series lead. After the completion of the series, Wong's health began to deteriorate. In late 1953 she suffered an internal haemorrhage, which her brother attributed to the onset of menopause, her continued heavy drinking, and financial worries.

In the following years, she did guest spots on television series. In 1960, she returned to film playing housekeeper to Lana Turner in the thriller Portrait in Black (Michael Gordon, 1960). She was scheduled to play the role of Madame Liang in the film production of Rodgers and Hammerstein's Flower Drum Song (Henry Koster, 1961) when she died of a heart attack at home in Santa Monica in 1961.

Anna May Wong was 56. For decades after her death, Wong was remembered principally for the stereotypical sly ‘Dragon Lady’ and demure ‘Butterfly’ roles that she was often given. Anna May Wong never married, but over the years, she was the rumoured mistress of several prominent film men: Marshall Neilan (14 years older, supposedly Wong's lover when she was 15), director Tod Browning (23 years older, when she was 16) and Charles Rosher (Mary Pickford's favourite cinematographer, who was nearly 20 years older, when Wong was 20). But no biographer can say for sure that any of these affairs occurred.

Matthew Sweet in The Guardian: “And this is the trouble with Anna May Wong. We disapprove of the stereotypes she fleshed out - the treacherous, tragic daughters of the dragon - but her performances still seduce, for the same reason they did in the 1920s and 30s.” Her life and career were re-evaluated by three new biographies, a meticulous filmography, and a British documentary about her life, called Frosted Yellow Willows.

Wikipedia: “Through her films, public appearances and prominent magazine features, she helped to ‘humanize’ Asian Americans to white audiences during a period of overt racism and discrimination. Asian Americans, especially the Chinese, had been viewed as perpetually foreign in U.S. society but Wong's films and public image established her as an Asian-American citizen at a time when laws discriminated against Asian immigration and citizenship.”

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 6885/1, 1931-1932. Photo: Paramount.

Dutch postcard, no. 128. Photo: Paramount. Sent by mail in 1932.

German postcard by Ross Verlag. Photo: Paramount.

British postcard by James Gardiner Postcards, Watford in The Glamour Queens series, no. 15, 1988. Photo: Otto Dyar.

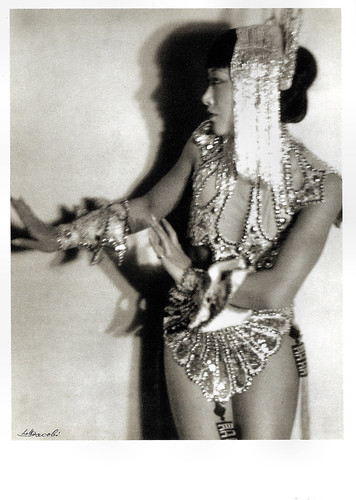

German postcard in the Ausdrucktstanz series by Galerie Bodo Niemann, Berlin, no. 08/10. Photo: Lotte Jacobi. Caption: Anna May Wong, Berlin, ca. 1931.

Anna May Wong in a clip of Piccadilly (1929). Source: BFI (YouTube).

Marlene Dietrich and Anna May Wong in a cheeky scene from Shanghai Express (1932). Source: JD Stirling (YouTube).

Sources: Le Giornate del Cinema Muto (Italian), Richard Corliss (Time), Matthew Sweet (The Guardian), Jon C. Hopwood (IMDb), Wikipedia and IMDb.

No comments:

Post a Comment