Every Thursday this summer, EFSP will post on a film book. On vacation in Italy, I read an interesting book on 'The Hollywood Ten', the screenwriters and directors, who in 1947, were charged by the House of Un-American activities for their associations with the Communist Party. Bruce Cook wrote a biography on the most famous of the ten, Dalton Trumbo. The film makers were blacklisted during the 1950s by the film industry, and some even jailed. Dalton Trumbo was the first who got his name on the big screen again, in the hit film Exodus (1960), and thus effectively demolished the Hollywood blacklist.

Book cover for Bruce Cook, 'Trumbo' (1977). Publisher: Grand Central Publishing, New York (edition 2015).

James Dalton Trumbo (1905-1976) was a radical. No doubt about that. During his career Trumbo frequently took unpopular left-leaning political positions, and Cook describes them in detail. He also explains where Trumbo's radicalism came from.

When his father died in 1926, Dalton Trumbo took a job in the Davis Perfection Bakery on the night shift to help support his widowed mother and younger sisters. He worked there for 8 years while cranking out countless short stories and novels. He hated the job at the bakery and later referred to it as 'Kind of a period of horror'. He became more and more anxious and eventually desperate to leave the bakery, fearing that he would never achieve his destiny of becoming an important writer.

Cook describes how during his years at the bakery, Trumbo began to split the world in two: them and us. Them at the bakery were the bosses he grew to hate, and at the other side were the boys of the bakery. He led a successful strike of key employees in the shipping department for better pay. Later, his years at the bakery were his credentials to his leftish buddies for who he was and why he was.

But Dalton Trumbo was more than a left-wing political activist. He became a very successful and highly paid screenwriter in Hollywood. Among his best known films are the romantic drama Kitty Foyle (Sam Wood, 1940) which starred Ginger Rogers and earned Trumbo his first Academy Award nomination, the patriotic war drama Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo (Mervyn LeRoy, 1944), starring Spencer Tracy and Robert Mitchum, the classic romance Roman Holiday (William Wyler, 1953) starring Gregory Peck and Audrey Hepburn, Stanley Kubrick's Spartacus (1960), and finally Papillon (Franklin J. Schaffner, 1973), starring Steve McQueen and Dustin Hoffman.

After Trumbo was blacklisted by the film industry in 1947, his sheer talent enabled him to continue working clandestinely on top films, writing under other authors' names or pseudonyms. An example is the Film Noir classic Gun Crazy (Joseph H. Lewis, 1949), co-written under the pseudonym Millard Kaufman. His uncredited work won two Oscars: for Roman Holiday (William Wyler, 1953) which award was given to his front, screenwriter Ian McLellan Hunter, and for The Brave One (Irving Rapper, 1956) which was awarded to a pseudonym of Trumbo.

British postcard by Art Photo. Photo: Warner Bros / Vitaphone Pictures. Patricia Ellis was called "the Queen of B pictures at Warner Brothers". She was the star of Love Begins at 20 (Frank McDonald, 1936), the second film (co-)written by Trumbo.

Dutch postcard by J.S.A. Photo: M.P.E. Maureen O'Hara was the star of the drama A Bill of Divorcement (John Farrow, 1940) for which Trumbo wrote the script. When his first studio, Warner Bros., tried to force Trumbo to switch unions — from the Screen Writers Guild, run by John Howard Lawson, to a more pliable upstart, the Screen Playwrights — he refused, and the studio voided his contract. He later managed to sell eight scripts to RKO. A Bill of Divorcement was a rather disappointing remake of the 1932 film with Katharine Hepburn.

Italian postcard by B.F.F. Edit., no. 2255. Photo: RKO Radio. Trumbo also wrote the script for the romantic comedy You Belong to Me (Wesley Ruggles, 1941) for RKO. Henry Fonda played a jealous and insecure newlywed man, who interferes with his wife's medical work in order to prevent her from seeing attractive male patients.

French postcard by Erpé, no. 550. Photo: Film Radio (RKO). Trumbo’s big film break was Kitty Foyle (Sam Wood, 1940) starring Ginger Rogers, for which he was nominated for an Academy Award. During the war he wrote a number of screenplays and in 1943, after being a fellow traveller for years, Trumbo decided to join the Communist Party. Ginger Rogers starred also in his Tender Comrade (Edward Dmytryk, 1943), showing women on the home front living communally while their husbands are away at war. The film was later used by the HUAC as evidence of Dalton Trumbo spreading communist propaganda.

Italian postcard by Bromofoto, Milano, no. 563. Photo: Peggy Cummins in Gun Crazy (Joseph H. Lewis, 1949). The day after returning from the hearings, Trumbo was contacted by independent producer Frank King who asked if he’d like to write a B-Picture called Gun Crazy. Thus began a long period where Trumbo successfully wrote scripts under many pseudonyms or a friend’s name, continuing to feed his pressing need for money. In Mexico, Trumbo wrote 30 scripts under pseudonyms for B-movie studios such as King Brothers Productions. He adapted Gun Crazy, from a short story by MacKinlay Kantor, Kantor agreed to be the front for Trumbo's screenplay. Trumbo's role in the screenplay was not revealed until 1992.

In October 1947, as postwar paranoia about the perceived threat of Communism was ramping up in the United States, Trumbo was among a group of 10 Hollywood directors and writers called to testify before the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC), which was charged with investigating whether Communist sympathisers had propagandised American audiences.

Trumbo and the other nine individuals summoned all refused to testify, and as a consequence, the 'Hollywood Ten” were found guilty of contempt of Congress. They were subsequently blacklisted by the heads of the major studios, and in 1950 Trumbo served almost a year in prison. Trumbo and the other screenwriters were also kicked out of the Screen Writers Guild, while one of the ten, John Howard Lawson had been one of the founders of the SWG and its first president. This meant that they could not obtain work in Hollywood, even if they had not been blacklisted. After his blacklisting and the failure of the Hollywood 10's appeals, the Trumbo family exiled themselves to Mexico in a tight-knit community with other blacklist exiles, including Ring Lardner Jr. and Albert Maltz.

Finally, in 1957, after nearly a decade of working in exile, Trumbo at last saw an opportunity to return to Hollywood. His screenplay for The Brave One, which he had written under the pseudonym Robert Rich, received an Academy Award. When journalists were subsequently unable to find the mysterious Robert Rich for comment, it was soon surmised that the film had in fact been written by Trumbo. This and other similar incidents involving blacklisted writers led to a general reexamination of the practice, with support for the concept quickly weakening in the industry.

When Dalton Trumbo was given public screen credit for both Exodus and Spartacus in 1960. Trumbo's one-two epic punch effectively ended the Hollywood Blacklist for himself and other screenwriters. However it still took several years before was given full credit by the Writers' Guild for all his achievements, the work of which encompassed six decades of screenwriting.

Trumbo's life as a 'swimming-pool communist' is a great story. He ran a chauffeur-driven Chrysler, smoked six packs a day and wrote in the bath. He collected pre-Columbian art in Mexico. And he delighted in throwing splashy parties. Bruce Cook's well-written and extensively researched biography reads like an adventure novel. He spoke several times with Trumbo before his death in 1976 and also with his family and colleagues, but Cook does not turn him into a Mr. Nice Guy. In fact, after reading the book, I still wonder if I like Dalton Trumbo as a person. His character was contradictory. He could turn on people without warning and ruthlessly demolish them with his sharp tongue. But he was also extremely generous, going out of his way to help colleagues with ideas, contacts or money.

Trumbo's sympathies coincided with those of the American Communist Party (CPUSA), which hewed to the line set by Moscow. He joined the CPUSA in 1943 at a time when everybody in the world fought Adolf Hitler. But after the war when it became known that Joseph Stalin had sent and continued to send millions of Russians to the gulags (18 millions between 1930 and 1953 of which roughly 1.5 to 1.7 million perished there or as a result of their detention), Trumbo stayed a true believer. Bruce Cook definitively makes clear that the 'Hollywood 10' had a tough time in the US of the 1950s and the blacklisting tragically broke several careers and lives, but I can't help wondering: would these radicals have survived the horrors of the USSR during the same period?

Another aspect of the book which annoyed me sometimes is the snobbery about writing literature. Authoring a literary novel is seen by many of the interviewed - and seemingly also by Cook - as far more important than penning scripts for the movies. Lots of pages are written about Trumbo's literary efforts, while most of them seem righteously forgotten now. I would have preferred to read more about his film writing, for which he is primarily known. When Bruce Cook at the end of the book dives into Dalton Trumbo's ability to create a successful script, then 'Trumbo' suddenly flies for me.

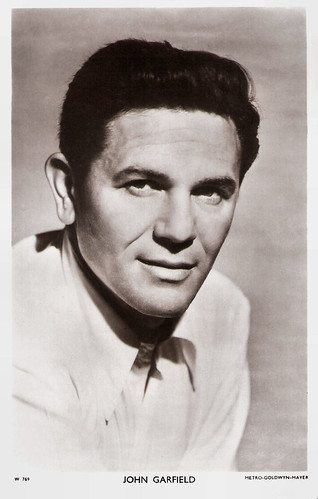

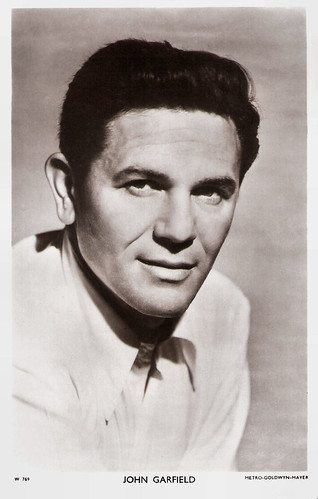

British postcard in the Picturegoer Series, no. W 769. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. American actor John Garfield was called to testify before the U.S. Congressional House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC), he denied communist affiliation and refused to 'name names', which effectively ended his film career. In 1952, the stress led to his premature death at 39 from a heart attack. His final film was the Film Noir He Ran All the Way (John Berry, 1951), with Shelley Winters, and written by Trumbo and Hugo Butler with Guy Endore as the front.

British postcard by Real Photographs Co., Ltd, Victoria House, Southport. In the Film Noir The Prowler (Joseph Losey, 1951), Evelyn Keyes plays a gorgeous housewife, who finds a prowler outside her house late one night and calls the police. Although Trumbo never set foot on the set, he and Losey worked closely together. Trumbo's voice can be heard throughout the film as Keyes' husband, who works as an all-night disc jockey. So Trumbo dubbed the deejay's patter which he himself had written.

German postcard by Kunst und Bild, Berlin, no. A 1079. Photo: Paramount. Audrey Hepburn and Gregory Peck in Roman Holiday (William Wyler, 1952). The most truly original of all the original scripts Dalton Trumbo wrote during his blacklist period. The most charming and distinctive film of Trumbo's career. His credit was reinstated when the film was released on DVD in 2003. In 2011, full credit for Trumbo's work was restored.

German postcard by Kolibri-Verlag, no. 1102. Photo: Corona / Schorchtfilm. Scott Brady in Mannequins für Rio/They were so Young (Kurt Neumann, 1954). For low-budget studio Lippert Pictures, Dalton Trumbo wrote this German-American melodrama (under the pseudonym Felix Lützkendorf) about a German girl lured to Brazil for 'modeling' work but trapped in a white slavery racket. Scott Brady was the good, American guy who saves the girl.

Romanian collectors card. Photo: Kirk Douglas and Peter Ustinov in Spartacus (Stanley Kubrick, 1960). Gradually during the 1950s the blacklist weakened. With the support of director Otto Preminger, Trumbo was credited for the screenplay of Exodus (1960), adapted from the novel of Leon Uris. Shortly thereafter, Kirk Douglas announced Trumbo had written the screenplay for Spartacus, adapted from the novel by Howard Fast. With these actions, Preminger and Douglas helped end the power of the blacklist. Trumbo was reinstated into the Writers Guild of America, West and was credited on all subsequent scripts.

Sources: David L. Dunbar (The Hollywood Reporter), Biography.com, Jon C. Hopwood (IMDb), The Telegraph, Wikipedia and IMDb.

Book cover for Bruce Cook, 'Trumbo' (1977). Publisher: Grand Central Publishing, New York (edition 2015).

His credentials for who he was and why he was

James Dalton Trumbo (1905-1976) was a radical. No doubt about that. During his career Trumbo frequently took unpopular left-leaning political positions, and Cook describes them in detail. He also explains where Trumbo's radicalism came from.

When his father died in 1926, Dalton Trumbo took a job in the Davis Perfection Bakery on the night shift to help support his widowed mother and younger sisters. He worked there for 8 years while cranking out countless short stories and novels. He hated the job at the bakery and later referred to it as 'Kind of a period of horror'. He became more and more anxious and eventually desperate to leave the bakery, fearing that he would never achieve his destiny of becoming an important writer.

Cook describes how during his years at the bakery, Trumbo began to split the world in two: them and us. Them at the bakery were the bosses he grew to hate, and at the other side were the boys of the bakery. He led a successful strike of key employees in the shipping department for better pay. Later, his years at the bakery were his credentials to his leftish buddies for who he was and why he was.

But Dalton Trumbo was more than a left-wing political activist. He became a very successful and highly paid screenwriter in Hollywood. Among his best known films are the romantic drama Kitty Foyle (Sam Wood, 1940) which starred Ginger Rogers and earned Trumbo his first Academy Award nomination, the patriotic war drama Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo (Mervyn LeRoy, 1944), starring Spencer Tracy and Robert Mitchum, the classic romance Roman Holiday (William Wyler, 1953) starring Gregory Peck and Audrey Hepburn, Stanley Kubrick's Spartacus (1960), and finally Papillon (Franklin J. Schaffner, 1973), starring Steve McQueen and Dustin Hoffman.

After Trumbo was blacklisted by the film industry in 1947, his sheer talent enabled him to continue working clandestinely on top films, writing under other authors' names or pseudonyms. An example is the Film Noir classic Gun Crazy (Joseph H. Lewis, 1949), co-written under the pseudonym Millard Kaufman. His uncredited work won two Oscars: for Roman Holiday (William Wyler, 1953) which award was given to his front, screenwriter Ian McLellan Hunter, and for The Brave One (Irving Rapper, 1956) which was awarded to a pseudonym of Trumbo.

British postcard by Art Photo. Photo: Warner Bros / Vitaphone Pictures. Patricia Ellis was called "the Queen of B pictures at Warner Brothers". She was the star of Love Begins at 20 (Frank McDonald, 1936), the second film (co-)written by Trumbo.

Dutch postcard by J.S.A. Photo: M.P.E. Maureen O'Hara was the star of the drama A Bill of Divorcement (John Farrow, 1940) for which Trumbo wrote the script. When his first studio, Warner Bros., tried to force Trumbo to switch unions — from the Screen Writers Guild, run by John Howard Lawson, to a more pliable upstart, the Screen Playwrights — he refused, and the studio voided his contract. He later managed to sell eight scripts to RKO. A Bill of Divorcement was a rather disappointing remake of the 1932 film with Katharine Hepburn.

Italian postcard by B.F.F. Edit., no. 2255. Photo: RKO Radio. Trumbo also wrote the script for the romantic comedy You Belong to Me (Wesley Ruggles, 1941) for RKO. Henry Fonda played a jealous and insecure newlywed man, who interferes with his wife's medical work in order to prevent her from seeing attractive male patients.

French postcard by Erpé, no. 550. Photo: Film Radio (RKO). Trumbo’s big film break was Kitty Foyle (Sam Wood, 1940) starring Ginger Rogers, for which he was nominated for an Academy Award. During the war he wrote a number of screenplays and in 1943, after being a fellow traveller for years, Trumbo decided to join the Communist Party. Ginger Rogers starred also in his Tender Comrade (Edward Dmytryk, 1943), showing women on the home front living communally while their husbands are away at war. The film was later used by the HUAC as evidence of Dalton Trumbo spreading communist propaganda.

Italian postcard by Bromofoto, Milano, no. 563. Photo: Peggy Cummins in Gun Crazy (Joseph H. Lewis, 1949). The day after returning from the hearings, Trumbo was contacted by independent producer Frank King who asked if he’d like to write a B-Picture called Gun Crazy. Thus began a long period where Trumbo successfully wrote scripts under many pseudonyms or a friend’s name, continuing to feed his pressing need for money. In Mexico, Trumbo wrote 30 scripts under pseudonyms for B-movie studios such as King Brothers Productions. He adapted Gun Crazy, from a short story by MacKinlay Kantor, Kantor agreed to be the front for Trumbo's screenplay. Trumbo's role in the screenplay was not revealed until 1992.

Who is the mysterious Robert Rich?

In October 1947, as postwar paranoia about the perceived threat of Communism was ramping up in the United States, Trumbo was among a group of 10 Hollywood directors and writers called to testify before the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC), which was charged with investigating whether Communist sympathisers had propagandised American audiences.

Trumbo and the other nine individuals summoned all refused to testify, and as a consequence, the 'Hollywood Ten” were found guilty of contempt of Congress. They were subsequently blacklisted by the heads of the major studios, and in 1950 Trumbo served almost a year in prison. Trumbo and the other screenwriters were also kicked out of the Screen Writers Guild, while one of the ten, John Howard Lawson had been one of the founders of the SWG and its first president. This meant that they could not obtain work in Hollywood, even if they had not been blacklisted. After his blacklisting and the failure of the Hollywood 10's appeals, the Trumbo family exiled themselves to Mexico in a tight-knit community with other blacklist exiles, including Ring Lardner Jr. and Albert Maltz.

Finally, in 1957, after nearly a decade of working in exile, Trumbo at last saw an opportunity to return to Hollywood. His screenplay for The Brave One, which he had written under the pseudonym Robert Rich, received an Academy Award. When journalists were subsequently unable to find the mysterious Robert Rich for comment, it was soon surmised that the film had in fact been written by Trumbo. This and other similar incidents involving blacklisted writers led to a general reexamination of the practice, with support for the concept quickly weakening in the industry.

When Dalton Trumbo was given public screen credit for both Exodus and Spartacus in 1960. Trumbo's one-two epic punch effectively ended the Hollywood Blacklist for himself and other screenwriters. However it still took several years before was given full credit by the Writers' Guild for all his achievements, the work of which encompassed six decades of screenwriting.

Trumbo's life as a 'swimming-pool communist' is a great story. He ran a chauffeur-driven Chrysler, smoked six packs a day and wrote in the bath. He collected pre-Columbian art in Mexico. And he delighted in throwing splashy parties. Bruce Cook's well-written and extensively researched biography reads like an adventure novel. He spoke several times with Trumbo before his death in 1976 and also with his family and colleagues, but Cook does not turn him into a Mr. Nice Guy. In fact, after reading the book, I still wonder if I like Dalton Trumbo as a person. His character was contradictory. He could turn on people without warning and ruthlessly demolish them with his sharp tongue. But he was also extremely generous, going out of his way to help colleagues with ideas, contacts or money.

Trumbo's sympathies coincided with those of the American Communist Party (CPUSA), which hewed to the line set by Moscow. He joined the CPUSA in 1943 at a time when everybody in the world fought Adolf Hitler. But after the war when it became known that Joseph Stalin had sent and continued to send millions of Russians to the gulags (18 millions between 1930 and 1953 of which roughly 1.5 to 1.7 million perished there or as a result of their detention), Trumbo stayed a true believer. Bruce Cook definitively makes clear that the 'Hollywood 10' had a tough time in the US of the 1950s and the blacklisting tragically broke several careers and lives, but I can't help wondering: would these radicals have survived the horrors of the USSR during the same period?

Another aspect of the book which annoyed me sometimes is the snobbery about writing literature. Authoring a literary novel is seen by many of the interviewed - and seemingly also by Cook - as far more important than penning scripts for the movies. Lots of pages are written about Trumbo's literary efforts, while most of them seem righteously forgotten now. I would have preferred to read more about his film writing, for which he is primarily known. When Bruce Cook at the end of the book dives into Dalton Trumbo's ability to create a successful script, then 'Trumbo' suddenly flies for me.

British postcard in the Picturegoer Series, no. W 769. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. American actor John Garfield was called to testify before the U.S. Congressional House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC), he denied communist affiliation and refused to 'name names', which effectively ended his film career. In 1952, the stress led to his premature death at 39 from a heart attack. His final film was the Film Noir He Ran All the Way (John Berry, 1951), with Shelley Winters, and written by Trumbo and Hugo Butler with Guy Endore as the front.

British postcard by Real Photographs Co., Ltd, Victoria House, Southport. In the Film Noir The Prowler (Joseph Losey, 1951), Evelyn Keyes plays a gorgeous housewife, who finds a prowler outside her house late one night and calls the police. Although Trumbo never set foot on the set, he and Losey worked closely together. Trumbo's voice can be heard throughout the film as Keyes' husband, who works as an all-night disc jockey. So Trumbo dubbed the deejay's patter which he himself had written.

German postcard by Kunst und Bild, Berlin, no. A 1079. Photo: Paramount. Audrey Hepburn and Gregory Peck in Roman Holiday (William Wyler, 1952). The most truly original of all the original scripts Dalton Trumbo wrote during his blacklist period. The most charming and distinctive film of Trumbo's career. His credit was reinstated when the film was released on DVD in 2003. In 2011, full credit for Trumbo's work was restored.

German postcard by Kolibri-Verlag, no. 1102. Photo: Corona / Schorchtfilm. Scott Brady in Mannequins für Rio/They were so Young (Kurt Neumann, 1954). For low-budget studio Lippert Pictures, Dalton Trumbo wrote this German-American melodrama (under the pseudonym Felix Lützkendorf) about a German girl lured to Brazil for 'modeling' work but trapped in a white slavery racket. Scott Brady was the good, American guy who saves the girl.

Romanian collectors card. Photo: Kirk Douglas and Peter Ustinov in Spartacus (Stanley Kubrick, 1960). Gradually during the 1950s the blacklist weakened. With the support of director Otto Preminger, Trumbo was credited for the screenplay of Exodus (1960), adapted from the novel of Leon Uris. Shortly thereafter, Kirk Douglas announced Trumbo had written the screenplay for Spartacus, adapted from the novel by Howard Fast. With these actions, Preminger and Douglas helped end the power of the blacklist. Trumbo was reinstated into the Writers Guild of America, West and was credited on all subsequent scripts.

Sources: David L. Dunbar (The Hollywood Reporter), Biography.com, Jon C. Hopwood (IMDb), The Telegraph, Wikipedia and IMDb.

No comments:

Post a Comment