French postcard by Chromovogue, no. 10 155 A. Image: Walt Disney Pictures. Publicity still for Hercules (Ron Clements, John Musker, 1997).

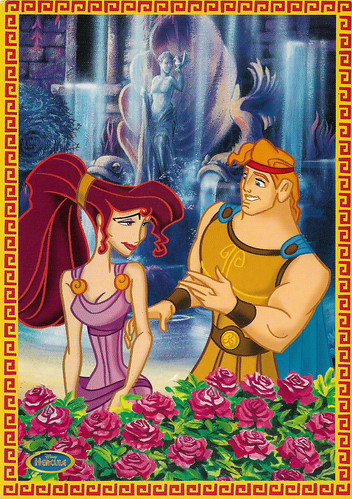

French postcard by Chromovogue, no. 10155 B. Image: Walt Disney Pictures. Meg and Hercules in Hercules (Ron Clements, John Musker, 1997).

Vintage postcard by European Greetings, no. 535730. Image: Disney. Meg in Hercules (Ron Clements, John Musker, 1997).

Three monstrous ladies who can see into the past, present and future

The story of Hercules (Ron Clements, John Musker, 1997) is told by the Muses. The film begins with an introduction telling how the Greek god Zeus defeated and imprisoned the Titans, bringing peace to the world. The story then moves several years into the future. Zeus and his wife Hera now live with the other Greek gods on Mount Olympus.

They have just given birth to their first child, Hercules (Herakles in Greek). All the gods come to celebrate this joyous event. As a birth present, Hercules receives from his father Pegasus, which Zeus made from a cloud. Yet not everyone is happy about Hercules' birth. Hades, the god of the underworld, fears that Hercules will disrupt his plans to seize power on Olympus.

A visit by the Fates, three monstrous ladies who can see into the past, present and future, confirms this suspicion. Hades plots a plan to get rid of Hercules. He has Hercules kidnapped by his henchmen Pain and Panic. They must make him mortal through a special potion and then kill him. However, they are disturbed by a peasant couple. As a result, Hercules does not drink the last drop of the potion and retains his divine power. However, he is mortal and therefore cannot return to Olympus.

He is adopted by the couple. Pain and Panic decide to keep this news to themselves and tell Hades that Hercules is dead. Years later, Hercules gets into more and more trouble with his colossal strength. When his parents tell him they have found him, he decides to go to the temple of Zeus. Zeus appears to Hercules and tells him who he really is. He also tells Hercules that he can regain his divinity if he proves to be a true hero. Hercules regains his old friend Pegasus, who is now also an adult.

He sends Hercules to the satyr Philoctetes, called 'Phil', to be trained as a hero. Phil first refuses as he has had bad experiences with heroes, but agrees after Zeus strikes him with a thunderbolt. A long training session follows. After the training, Phil and Hercules go to Thebes with Pegasus. On the way, Hercules rescues a woman named Meg from a centaur. What he does not know is that Meg actually works for Hades, having sold her soul to him years ago.

French postcard by Chromovogue, no. 10 155 C. Image: Walt Disney Pictures. Publicity still for Hercules (Ron Clements, John Musker, 1997).

French postcard by Chromovogue, no. 10 156 B. Image: Walt Disney Pictures. Publicity still for Hercules (Ron Clements, John Musker, 1997).

German lobby card. Image: Walt Disney Pictures. Little Pegasus and Hercules in Hercules (Ron Clements, John Musker, 1997).

Disney put its own spin on the mythological story

Hercules (Ron Clements, John Musker, 1997) has virtually nothing to do with the original stories of Hercules. John Musker and Ron Clements were attracted by the mythological aspect of the film and decided in the autumn of 1993 to direct and produce the film, with the help of Alice Dewey. Musker and Clements spent nine months defining the storyline, developing the initial script, and working with Andy Gaskill on the overall visuals; Gaskill then oversaw the art direction.

Animators spent the summer of 1994 in Greece to draw inspiration from the natural settings and archaeological sites, while British political cartoonist Gerald Scarfe helped to create the characters. Animation began in early 1995 and required nearly 700 artists, as well as Disney's first use of digital (computer-assisted) morphing.

Disney put its own spin on the mythological story. This was done partly because they felt certain events from mythology were inappropriate for young viewers. First of all, in the film, Hercules is the son of Zeus and Hera. In mythology, however, he is an illegitimate child of Zeus with the earthly woman Alcmene. Hera herself, in mythology, is Hercules' adversary. The Fates in the film are a fusion of the Fates goddesses and the Graeae.

In the film, the Titans are monstrous creatures, while in mythology they had a human appearance like the Greek gods. Possibly, in the film, the Titans are partly based on the Giants. Furthermore, some events from Greek mythology have been incorporated into the film in the wrong order. For instance, in Phil's home, Hercules collides with a piece of the Argo's mast, implying that the adventure of Jason and the Argonauts has already taken place. In mythology, however, Hercules was a member of the crew of the Argo.

Also, in the film, the Trojan War apparently took place before Hercules' training, while in mythology the war took place a generation after Hercules. Another difference in the film is that fear and panic work for Hades. In Greek mythology, they are sons of Ares and Aphrodite and have nothing to do with Hades.

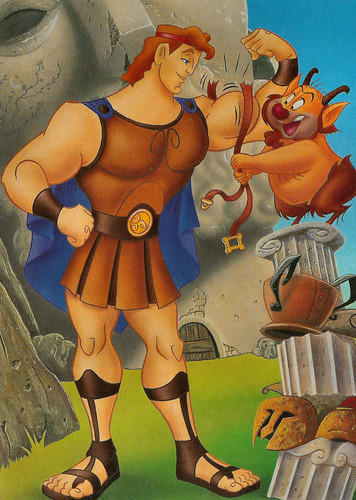

Vintage postcard by European Greetings, no. 553730. Image: Disney. Hercules and Phil in Hercules (Ron Clements, John Musker, 1997).

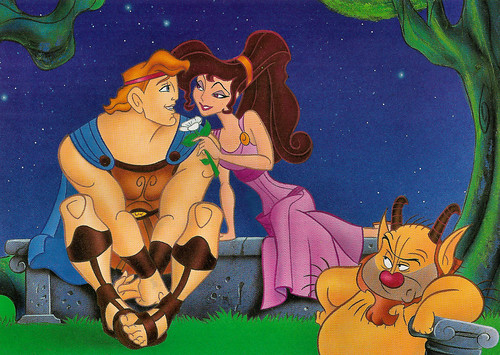

Vintage postcard by European Greetings, no. 553730. Image: Disney. Hercules, Meg and Phil in Hercules (Ron Clements, John Musker, 1997).

Vintage postcard by European Greetings, no. 553730. Image: Disney. Hercules in Hercules (Ron Clements, John Musker, 1997).

Many parodies of American culture

Walt Disney Pictures has stereotyped many of the characters in Hercules (Ron Clements, John Musker, 1997). For instance, Hercules is portrayed more as a superhero than a god. The film also contains many parodies of American culture, such as the huge merchandising created around Hercules when he becomes a hero.

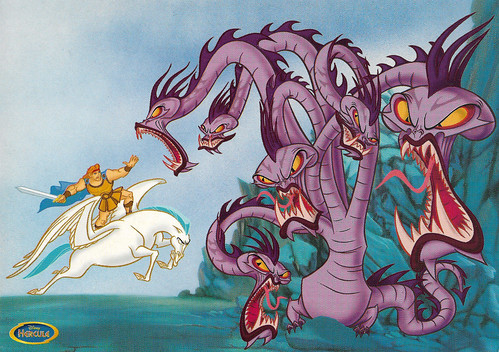

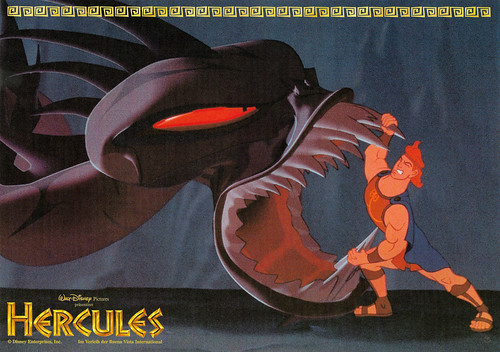

The film does contain references to the 12 works of Hercules from mythology, such as his battle with the Hydra. Most of these references are incorporated in the clip of the song 'Zero to Hero', and the tasks Phil lists while Hercules poses for a painter. In this scene, Hercules is clad in a lion skin: that of Scar, the mean lion from the Disney film The Lion King (Roger Allers, Rob Minkoff, 1994).

When the film was released in the United States, it received positive, though rarely enthusiastic, reviews from American critics. In the Chicago Sun-Times, Roger Ebert gave the film a rating of 3.5 out of 4 and praised the graphics, voices and pacing.

Roger Ebert: "Although I thought last summer's The Hunchback of Notre Dame was a more original and challenging film, Hercules is lighter, brighter and more cheerful, with more for kids to identify with. (...) The look of the animation has a new freshness because of the style of Scarfe, famous in England for his sharp-penned caricatures of politicians and celebrities; the characters here are edgier and less rounded than your usual Disney heroes (although the cuddly Pegasus is in the traditional mode). The color palette too, makes less use of basic colors and stirs in more luminous shades, giving the picture a subtly different look that suggests it is different in geography and history from most Disney pictures."

The film got a spin-off, the TV series Hercules: The Animated Series (1998). The series ran for 1 season with 65 episodes.

German lobby card. Image: Walt Disney Pictures. Hercules, Panic and Pain in Hercules (Ron Clements, John Musker, 1997).

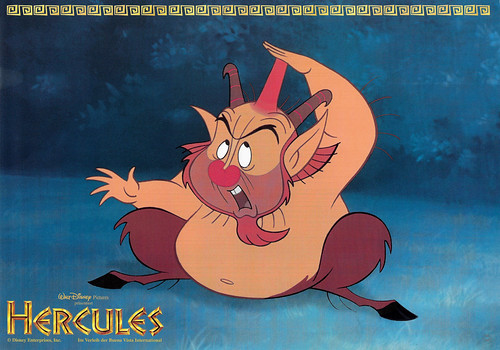

German lobbycard. Image: Disney. Phil in Hercules (Ron Clements, John Musker, 1997).

German lobbycard. Image: Disney. Panic and Pain in Hercules (Ron Clements, John Musker, 1997).

German lobby card. Image: Walt Disney Pictures. Hercules in Hercules (Ron Clements, John Musker, 1997).

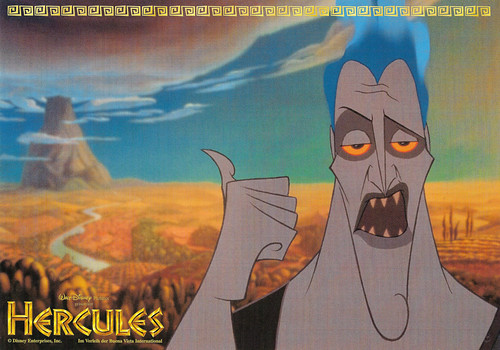

German lobby card. Image: Walt Disney Pictures. Hades in Hercules (Ron Clements, John Musker, 1997).

French double card by Mcdonalds'. Image: Walt Disney Pictures. Phil and Pegasus in Hercules (Ron Clements, John Musker, 1997).

Sources: Roger Ebert (Roger Ebert.com), Wikipedia (Dutch and French) and IMDb.

No comments:

Post a Comment