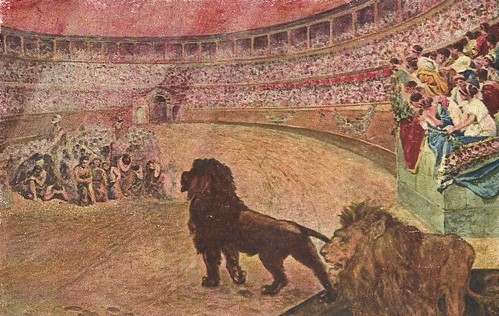

Italian postcard by Ed. E. Sborgi, Firenze. Art work by A. Del Senno. 'Çristiani al martirio'.The composition is a mirrored version of Jean-Léon Gérôme's painting 'The Christian Martyrs' Last Prayer'.

Italian postcard by Ed. G.B. Falci, Milano, La Fotominio, no. 166. Phoyo: Cines. Still from Quo vadis? (Enrico Guazzoni, 1913), used to promote the 1924 version directed by Gabriellino D'Annunzio and Georg Jacoby for U.C.I. Caption: The spectacles at the Circus Maximus. Depicted are the lions about to attack the Christian martyrs, to the sensation of the Roman public. The arena scenes from the 1913 version were so spectacular that they were re-inserted in various later films on Roman Antiquity. This particular image cites a well-known 19th-century painting: 'The Christian Martyrs' Last Prayer' (1883, Walters Art Museum) by the French 'archaeologist' painter Jean-Léon Gérôme.

Italian postcard. Photo: Cines. Scene from Quo vadis? (Enrico Guazzoni, 1913), adapted from the novel by Henryk Sienkiewicz. Caption: The Christians were exposed to the beasts at the circus.

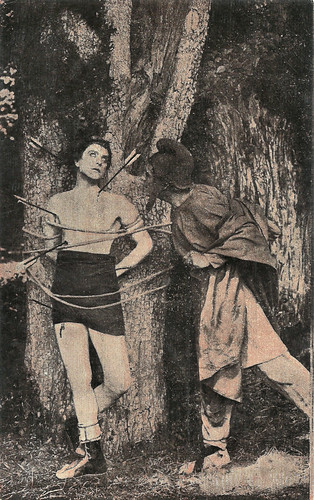

Spanish postcard for Amatller Marca Luna chocolate, series 8, no. 14. Photo: Palatino Film. Livio Pavanelli as St. Sebastiano in Fabiola (Enrico Guazzoni, 1918), hosting the blind Cecilia (Valeria Sanfilippo) on the request of the young Pancrazio (unknown).

Spanish postcard for Amatller Marca Luna chocolate, series 8, no. 16. Photo: Palatino Film. Livio Pavanelli as St. Sebastiano and Amleto Novelli as Fulvio in Fabiola (Enrico Guazzoni, 1918).

The ultimate Antichrist

In the early history of Christianity, Christian martyrs were tortured or killed by stoning, decapitation, crucifixion, death at the stake, or massacre by wild animals in the arena. Initially, martyrdom in Christianity denoted the endurance of sacrifice, hardship and physical privation to honour God, but later the term was applied to refer almost exclusively to Christians who were killed for their faith.

The first Christian martyrs ever were the apostles of Jesus, except for John, who died in exile. The period of early Christianity before the reign of Constantine is considered the ‘era of the martyrs’. The conventional setting of their stories is that of places of secret Eucharistic celebrations mostly at the Roman catacombs and conventionally they would wave palm branches, while early Christians would make secret signs to each other such as an emblem of a fish, even if 19th c. literature and early 20th c. films already indicate these signs were quickly picked up by their persecutors too.

Often in 19th c. literature featuring Christian martyrs such as 'Quo vadis?' by Henryk Sienkiewicz and 'Fabiola by Cardinal Wiseman, personal dealings like rejection and revenge lead to persecution of either the Christian protagonist, as in the martyrdom of saints like Cecilia or Sebastian, or even all Christians in Rome, as in 'Quo vadis?' and 'Fabiola'.

While in novels like 'Quo vadis?', Nero is presented as the ultimate Antichrist and debauched persecutor of the Christians, history has made clear that persecution of the Christians has been much more drastic under later emperors like Diocletian. Yet, in Arrigo Boito’s opera 'Nerone' of 1924, posthumously premiered as Boito already died in 1918, the reputation of Nero as persecutor of the Christians still prevails, and this of course also goes for the 1924 remake of the film Quo vadis/, in which Emil Jannings stars as the ultimate evil emperor, reminding us of the Nero’s of our own times.

According to the Catholic Catechism, the figure of the martyr is antithetical to that of the apostate, that is, the one who has betrayed the faith. Martyrs are honoured as saints or blessed, and through prayers, services and Eucharistic celebrations, their day of death is commemorated. This cult of martyrs is one of the forms of private and public expression of the Christian faith, rooted already in the first communities that had to confront their new doctrines first with the Jewish tradition and then with the Roman imperial tradition. Yet, it is in particular in more recent centuries that martyrdom in Roman Antiquity was presented to show good examples of strength, virtue, persistence, faith and self-denial, to inspire contemporary audiences to behave in the same way.

French postcard by RA, no. 109. Photo: A. Bert. Ida Rubinstein in 'Le Martyr de St. Sebastien' (1911). Ida Rubinstein (1885-1960) was a Russian-Ukrainian ballerina of the Ballets Russes, choreographer, actress and Maecenas from the Belle Epoque. After Rubinstein left the Ballets Russes, she founded her own dance company, the Ballet Ida Rubinstein, and had immediate success with 'Le Martyre de Saint Sébastien' (1911), with music by Claude Debussy, text by Gabriele D'Annunzio, and choreography by Michel Fokine and sets and costumes by Léon Bakst.

British postcard by Rotary Photo, no. 3208 A. Photo: W. & D. Downey, London. Publicity for the stage play 'The Sign of the Cross' (Wilson Barrett, 1895), starring Wilson Barrett as Marcus Superbus and Maud Jeffries as Mercia. The Rotary cards on 'The Sign of the Cross' are probably early 1900s. Caption: Mercia: A sign the master has spoken: you cannot harm me now. The play was a huge success in the US and UK and elsewhere and would be turned into two major films in 1914 and in 1932.

French postcard. Mounet-Sully, Albert Lambert, Louis Delaunay, Louis Ravet and Mlle Lucie Brille in the stage play 'Polyeucte' by Pierre Corneille, staged at the Théâtre de la Nature in Cauterets on 11 or 12 August 1906. Mounet-Sully played Polyeucte, Lambert Severus, and Brille Pauline. The play is based on the life of the martyr Saint Polyeuctus.

French postcard by Mazet-Pons, Béziers. A performance in the Arènes de Béziers, France, a theatre in summertime of 'Héliogabale' (1910). The Prayer of the Christians.

French postcard. 'L'Aube Chrétienne', by L'Avant-garde Caennaise. This was a local play, performed at Caen, France, in April 1912. Caption: Combat de Gladiateurs. NB The helmets look more like 16th-century Spanish helmets, while the shirts and shoes don't look very Roman either. This goes to confirm that every century, every decade and every region makes its own vision of Antiquity.

Italian postcard by Ed. G. Zoboli, Bologna. Scene from the opera 'Nerone' (1924) by Arrigo Boito (1842-1918). 'Nerone' premiered posthumously at La Scala on May 1, 1924, conducted by Arturo Toscanini in a version of the score completed by Toscanini, Vincenzo Tommasini, and Antonio Smareglia. The role of Nero, originally intended for Francesco Tamagno, was first performed by Aureliano Pertile. Act III: The Christian garden.

Recycling sets and props like ‘Roman’ furniture or fake statuettes

Sometimes these early martyrdoms were presented in art in more chaste versions, as happened during the Counter-Reformation in still Baroque, opulent versions, towards the late 18th century, in more austere versions. Yet, also in more explicit, shocking versions as in late 19th c. academic art, such as Jean-Léon Gérôme’s 'The Return of the Felines', showing the remains of the slaughtered martyrs, or Léon Bonnat’s 'Martyrdom of St. Denis', with the saint looking for his head after his decapitation.

Particularly active in the field of representing early martyrdom was the organisation Maison de la Bonne Presse in Paris, which, in addition to many written texts like its own books and journals, around 1900 released several lantern slides on the martyrdom of saints like Cecilia and Tarcisius. Selections were afterwards also turned into a postcard series. Bonne Presse also made a few films within this genre. Yet, the mainstay of martyrdom in early cinema was produced by French and Italian cinema, in particular by the companies Pathé Frères in Paris and Cines in Rome.

Remarkable in this respect is what today we would indicate as ‘sustainable’, as these early companies often recycled parts of sets as well as props like ‘Roman’ furniture or fake statuettes copied from classical museum objects in various films, or even within multiple sets within the same film. Like in literature, in early cinema too, early martyrdom is often provoked by jealous and vengeful suitors, rejected by the Christian hero or heroin.

In some cases, such as the two leads in 'Quo vadis?', they manage to escape persecution by fleeing from Rome, but both protagonists and secondary characters often perish because of the ‘pagan’ hatred against them and the cold, indifferent attitude of the mob and the elite. Yet, as in the play and later film adaptations of 'The Sign of the Cross', some non-Christian protagonists have a love for their Christian beloved that is stronger than fear of death, and voluntarily select to die with their beloved in the arena.

Such was the urge to insert Christian messages in sources previously not connected with it, that in 1910 the opera/ drama 'Héliogabale' by Emile Sicard had an important element of Christian martyrdom as well.

French postcard in the Collection Artistique de la Maison de la Bonne Presse, Paris. The martyrdom of St. Cecilia, set in Roman Antiquity, was a beloved subject in late 19th and early 20th-century Catholic visuals, including a film by the Roman Cines company, Cines: Santa Cecilia (Enrique Santos, 1911), starring Fernanda Negri Pouget.

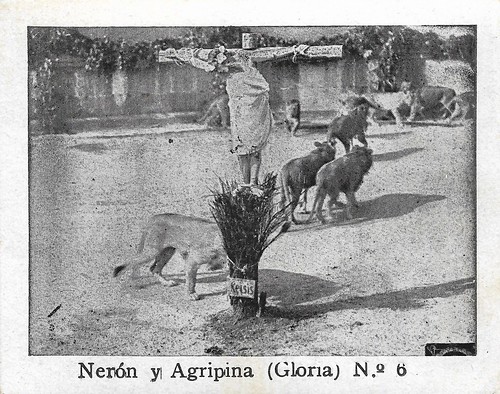

Spanish collector card by Reclam Films, Mallorca, card 6 of 6. Photo: Gloria Film. Scene from Nerone e Agrippina (Mario Caserini, 1914), starring Vittorio Rossi Pianelli as Nerone and Maria Caserini as Agrippina. Caption: Persecution of the Christians in the arena.

Italian postcard by Argentografica. Photo: Unione Cinematografia Italiana (UCI). Scene from Quo vadis? (Gabriellino D'Annunzio, Georg Jacoby, 1924), based on the classic novel by Henryk Sienkiewicz. Nero's human torches in his gardens.

Italian postcard by Argentografica. Photo: Unione Cinematografia Italiana (UCI). Scene from Quo vadis? (Gabriellino D'Annunzio, Georg Jacoby, 1924), based on the classic novel by Henryk Sienkiewicz. Christ has fallen under the Cross, the veil of Veronica.

French postcard. Photo: Metro Goldwyn Mayer. Ramon Novarro, Claire McDowell, May McAvoy and Kathleen Key in Ben-Hur (Fred Niblo, 1925).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 176/12. Photo: Paramount. Elissa Landi in the American epic The Sign of the Cross (Cecil B. DeMille, 1932), based on the original 1895 play by Wilson Barrett.

Workshops 'Silent Antiquity Prints Unique to the British National Film Archive', Wednesday 25 June 2025, 15:00 – 16:30 & 17:00 – 18:30, Aula Seminari, DAMsLab, Piazzetta P. P. Pasolini 5/b, 40122 Bologna.

No comments:

Post a Comment