Today, EFSP collaborator Ivo Blom will give a paper at a symposium at the Centre National pour la Cinématographie (CNC, Paris), within the framework of the Franco-Italian-Dutch research project LE CINÉMA MUET ITALIEN À LA CROISÉE DES ARTS EUROPÉENS (1896-1930). He will talk about the importance of painting, literature and theatre for two silent films with Italian diva Italia Almirante Manzini: Femmina (Augusto Genina, 1918) and L’ombra (Mario Almirante, 1923). Thus today's blog post is dedicated to the representation of artists and their models in the European silent cinema.

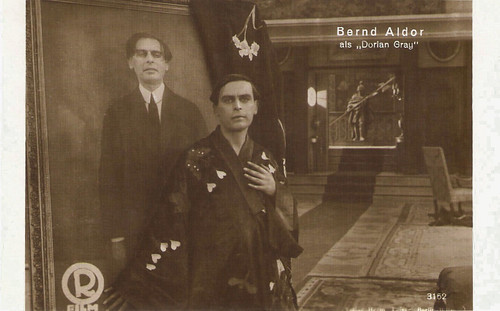

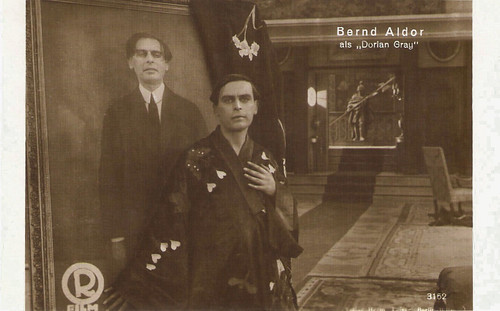

German postcard by Hermann Leiser Verlag, Berlin, no. 3152. Photo: Richard-Oswald-Produktion. Bernd Aldor in Das Bildnis des Dorian Gray/The Picture of Dorian Gray (Richard Oswald, 1917).

While Dorian remains the same beautiful young man in Das Bildnis des Dorian Gray/The Picture of Dorian Gray, his 'picture' becomes older, uglier, more depraved. Oscar Wilde’s haunting tale was filmed various times.

German postcard by Rotophot in the Film-Sterne series, no. 544/2. Photo: Hella Moja-Film GmbH. Hella Moja and Ernst Hofmann in Wundersam ist das Märchen der Liebe/Wonderful is the Fairy-Tale of Love (Leo Connard, 1918).

Cinema’s vision of the painter’s studio often has the model standing on a pedestal, the painter dressed in immaculate clothing, and the floor covered with oriental rugs.

German postcard by Rotphot in the Film Sterne series, no. 549/2. Photo: Decla. Ressel Orla in Die Sünde/The Sin (Alwin Neuss, 1918).

German postcard by Rotophot in the Film Sterne series, no. 549/4. Photo: Decla. Ressel Orla in Die Sünde/The Sin (Alwin Neuss, 1917).

“In Sin, Ressel Orla has first to play the young thing, who becomes an artist's model under the force of circumstances, in order to save her dying father. When she later stands alone in the world, she rises to happiness without suffering from her past. But then the pride of the woman awakens in her, to whom only the right of her own ego applies.” (Lichtbild-Bühne, 13.07.1918). As often happens in 1910s cinema, the model is ashamed by the artwork based on her own nudity when publicly exhibited, and even awarded.

German postcard by Rotophot in the Film-Sterne series, no. 514/4. Photo: Fern Andra Atelier. Fern Andra and (in the back) Alfred Abel in Ein Blatt im Sturm... doch das Schicksal hat es verweht/A leaf in a storm ... but fate has lost it (Fern Andra, 1917).

In 1910s cinema, the female partners of artists often need to help them out by selling their art, or even their own bodies.

German postcard by Rotophot in the Film Sterne series, no. 516/2. Photo: May Film. Mia May and Bruno Kastner in Ein Lichtstrahl im Dunkel/A Ray of Light in the Dark (Joe May, 1917).

Count Gerd Palm (Kastner) is known for his flattering portraits of his models, so countess Lydia von Grabor (May), who has a hideous nose, asks him to paint her. Gerd sees through her facade and paints her as a lovely mother. He is so enchanted by a song from her that he asks her marry him. Lydia cannot believe him, so he flees. Years pass, the counts has her nose operated, and returns to Gerd, but discovers he has become blind. Dressed as a nurse she takes care of him. Her care makes him retake his work. He hears she is now ready to marry him, but when he still doubts she sings the song she once sang for him and they finally unite.

German postcard by Photochemie, no. K. 2511. Photo: Saturn-Film. Maria Widal in Das sterbende Modell/The dying model (Urban Gad, 1918).

German postcard by Photochemie, no. K. 2510. Photo: Saturn-Film. Maria Widal in Das sterbende Modell/The dying model (Urban Gad, 1918).

Das sterbende Modell seems to have been a variation on Edgar Allen Poe’s 'The Oval Portrait'. The more the model is painted, the more she weakens and eventually dies. Painted portraits may have devastating effects on their models.

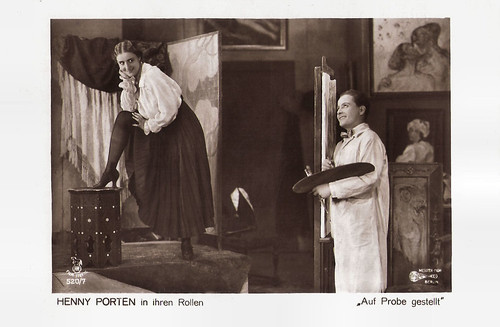

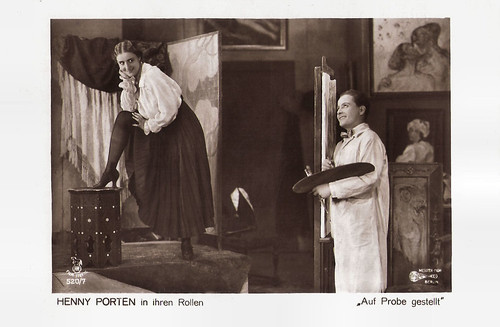

German postcard in the Film Sterne series by Rotophot, no. 520/7. Photo: Messter Film, Berlin. Henny Porten and Hermann Thimig in Auf Probe gestellt/Put to the test (Rudolf Biebrach, 1918).

Comedies with artists are rather rare in the 1910s, but a good example is this Henny Porten comedy. As 1910s film convention demands it, the countess prefers the poor, handsome painter to a rich and stupid aristocrat.

Spanish collectors card by Amattler Marca Luna chocolate, Series 6, no. 2. Photo: Eclipse. Fred Zorilla and Jean Aymé in Lorena (Georges Tréville, 1918)

Lorena (Suzanne Grandais) is the daughter of the marquis of Chambrey (Maillard), and secretly engaged to the painter Pierre Laurent (Fred Zorilla), but her father has other plans. He wants to give her hand to Count Borgo (Jean Aymé), a son of a late friend. As mentioned above, poor but young, handsome, romantic artists were often opposed to old, rich, depraved, and cynic or stupid aristocrats.

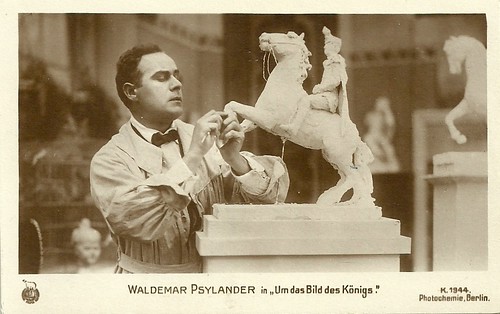

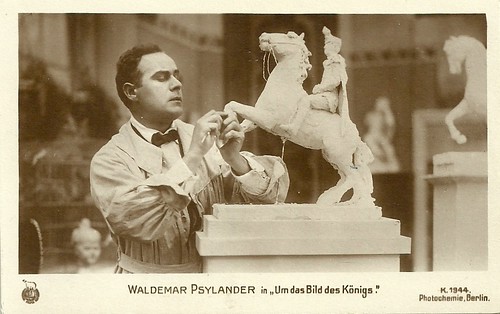

German postcard by Photochemie, Berlin, no. K. 1944. Photo: Nordisk Films. Valdemar Psilander in Rytterstatuen (A.W. Sandberg, 1919). The German title is Um das Bild des Königs (For the king's statue).

A young sculptor is commissioned by the Minister to make an equestrian statue of the King, for a high sum of money. He also meets and falls in love with the Minister’s niece. Her father, a banker, is involved in wild speculation, kills himself and leaves a giant debt. Secretly, the artist helps out with his prize money, winning the girl of course. So the artist is not only talented but also a gentleman.

Spanish postcard by Amatller Marca Luna chocolate, Series 2a, no. 6. Photo: Caesar Film. Gustavo Serena and Francesca Bertini in Il processo Clémenceau (Alfredo De Antoni, 1917). In Spain, the film was released as El proceso Clemenceau.

Il processo Clemenceau (Alfredo De Antoni, 1917) is typical for the parabolas in film plots on artists and their models. Artists discover models, often as young, beautiful and innocent girls. Gradually, the women become depraved thanks to the success of the artists, get hooked on money and luxury, and start to cheat. When the sculptor discovers his lover’s betrayal, he first will smash the plaster bust. In the end he will kill the model too. The artist creates the art work and also the model, but when the model misbehaves and does not correspond anymore with the art work’s purity, he may also destroy both the art work and the model. On the left of the card, a copy of a bust made by Amleto Cataldi, portraying Francesca Bertini, and published in the art journal Emporium in 1917.

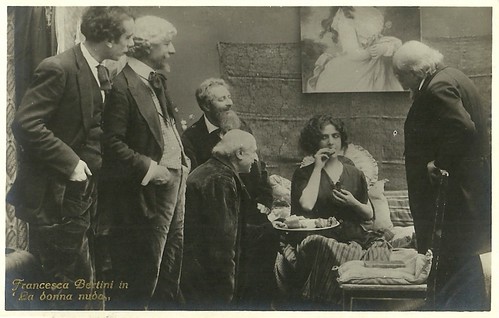

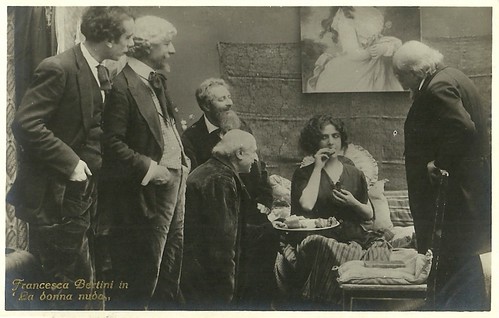

Italian postcard by G.B. Falci, Milano, no. 257. Photo: Caesar Film. Francesca Bertini in La donna nuda (Roberto Roberti, 1922), film adaptation of Henry Bataille's classic play La femme nue (1908).

Italian postcard by La Fotominio / Ed. G.B. Falci, Milano, no. 115. Photo: Caesar Film. Francesca Bertini and Angelo Ferrari in the Henry Bataille adaptation La donna nuda (Roberto Roberti, 1922).

Italian postcard by La Fotominio / Ed. G.B. Falci, Milano, no. 264. Photo: Caesar Film. Angelo Ferrari and Francesca Bertini in the Henry Bataille adaptation La donna nuda (Roberto Roberti, 1922).

In La donna nuda (Roberto Roberti, 1920), the painter Pierre Bernier (Angelo Ferrari) becomes acquainted with Lolette (Francesca Bertini), the model of his old friend Rouchard, picked up from the street. Lolette becomes Pierre’s model and his mistress. Pierre becomes famous thanks to his portrait 'The Naked Woman' which represents Lolette. The evening of his triumph at the Salon he decides to marry her, but after having become rich and famous he falls in love with the Princess of Chaban and abandons Lolette, despite owing her his success. After a suicide attempt over her persistently infidel lover, Lolette recovers in the hospital, rejects Pierre, and decides to return to Rouchard. The film was a remake of a film with Lyda Borelli, made in 1914 by Carmine Gallone, while several sound adaptations of Bataille's play would follow.

Italian postcard by IPA CT, no. 3654, V. Uff. Rev. St., Terni. Photo: Ambrosio. Umberto Mozzato as Settala and Mercedes Brignone as his wife Silvia in La Gioconda (Eleuterio Rodolfi 1916, released 1917), based on Gabriele D'Annunzio's play. Caption: 'Lucio Settala in the happy intimacy of the family.'

Italian postcard by IPA CT, no. 3877, V. Uff. Rev. St., Terni. Photo: Ambrosio. Umberto Mozzato as Lucio Settala and Helena Makowska as Gioconda Dianti in La Gioconda (1917).Caption: Sculptor Lucio Settala feels his love for his model Gioconda Dianti is ever expanding.

Italian postcard by IPA CT, no. 3871. Photo: Società Ambrosio, Torino. V. Uff. Rev. St. Terni. Mercedes Brignone in La Gioconda (Eleuterio Rodolfi, 1917). Caption: Sivia Settala deposes flowers in the studio of her husband, constating with great sadness, that he is ever more absent.

Italian postcard. IPA CT, no. 3662. Photo: Società Ambrosio, Torino. Helena Makowska as the model Gioconda Dianti in La Gioconda (Eleuterio Rodolfi, 1917).

Postcards for the lost Ambrosio production La Gioconda (Eleuterio Rodolfi, 1916, released 1917), based on Gabriele D'Annunzio's play, and starring Helena Makowska, Umberto Mozzato, and Mercedes Brignone. The statue for which Gioconda Danti poses does not seem to recall any existing statue, but its style reminds of that of the Italian sculptor Leonardo Bistolfi. As was common in silent films on artists, the actor’s studio is full of plasters referring to Antique and modern sculpture.

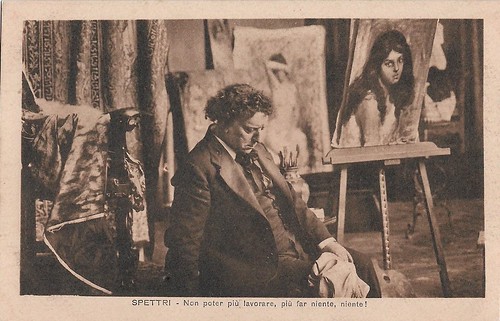

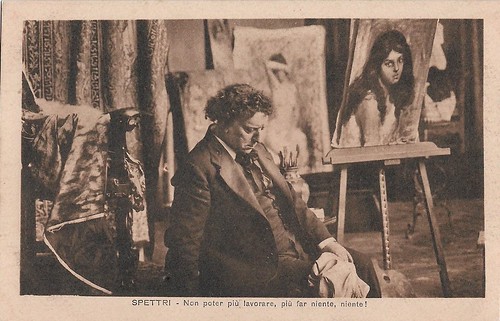

Italian postcard. Photo: Milano Film. Ermete Zacconi in Spettri/Gli spettri (A.G. Caldiera, 1918). Caption: Not being able anymore to paint, to do anything, nothing!

Ermete Zacconi in the Italian silent film Spettri/Gli spettri (A.G. Caldiera, 1918), adapted from Henrik Ibsen's play 'Ghosts' (Gengangere, 1881). Caption: Not being able anymore to paint, to do anything, nothing! Oswald Alving, who has been a painter in Paris, returns home, suffering from depressions. He gets into a state of despair and anguish, when his mother reveals him the woman he loves is his half-sister and he is himself suffering of syphilis, inherited from his father. He asks his mother to help him die by an overdose of morphine in order to end his suffering from his disease, which could put him into a helpless vegetative state.

Italian postcard by Fotominio, no. 52. Photo: G.B. Falci, Milano. Italia Almirante in La statua di carne (Mario Almirante 1921). Noemi Keller notices the painted portrait of her lookalike Maria, who has died and whom the painter, count Paolo, is still loving, through Noemi.

La statua di carne (Mario Almirante, 1921), starring Italia Almirante Manzini and Lido Manetti. Often in film, deceased persons affect the living ones by their painted portraits. When discovering a painted portrait of the deceased ‘midinette’ Maria, who is her exact lookalike, the mundane stage artist Noemi Keller understands why count Paolo is so obsessed with her. The motif of the Doppelgänger was popular in silent film and in literature. Though based on an original play (1862, by Teobaldo Ciconi, which was already adapted to film in Italy in 1912, the plot of La statua di carne may also remind of the Symbolist novel 'Bruges-la-morte' (1892) by Georges Rodenbach, which inspired various films such as Yevgeni Bauer’s Gryozy/ Daydreams (1915) and Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1959).

Italian postcard by Ed. Ballerini & Fratini, Firenze. Photo: Liliana Ardea and Alberto Collo in L'ombra (Mario Almirante, 1923). Caption: Berta's little friend and the daily painting lesson.

Italian postcard by Ed. Ballerini & Fratini, Firenze, no. 242. Photo: Liliana Ardea and Alberto Collo in L'ombra (Mario Almirante, 1923). Caption: In the new house of Gerardo. Elena: He is your real masterpiece!

Italian postcard by Ed. Ballerini & Fratini, Firenze, no. 248. Photo: Italia Almirante Manzini and Alberto Collo in L'ombra (Mario Almirante, 1923). Caption: Berta: Poor little one! He won't realise to have changed mother. This image represents the final scene of the film.

In L’ombra (Mario Almirante, 1924), Berta (Italia Almirante Manzini) is paralysed. Her husband Gerardo (Alberto Collo), an acclaimed painter, starts a double life with Elena (Liliana Ardea), a former pupil. He even has a child with her. The paralysed woman heals, discovers the fraud, and is devastated, preferring to get paralysed again. In the end, the second woman exits, leaving even her child behind. Mark the unfinished portrait of the child on the right. In the play by Dario Niccodemi, on which the film is based, the interior of the painter’s house is described as being full with portraits of the child.

Sources: Ivo Blom, ‘Of Artists and Models. Italian Silent Cinema between Narrative Convention and Artistic Practice’ (Acta Sapientiae Universitatis. Film and Media Studies 7, 2013, 97-110) and Francesco Geraci, ‘Artisti contemporanei: Amleto Cataldi’ (Emporium, XLV, Vol. 267, March 1917, pp. 163-175).

German samples

German postcard by Hermann Leiser Verlag, Berlin, no. 3152. Photo: Richard-Oswald-Produktion. Bernd Aldor in Das Bildnis des Dorian Gray/The Picture of Dorian Gray (Richard Oswald, 1917).

While Dorian remains the same beautiful young man in Das Bildnis des Dorian Gray/The Picture of Dorian Gray, his 'picture' becomes older, uglier, more depraved. Oscar Wilde’s haunting tale was filmed various times.

German postcard by Rotophot in the Film-Sterne series, no. 544/2. Photo: Hella Moja-Film GmbH. Hella Moja and Ernst Hofmann in Wundersam ist das Märchen der Liebe/Wonderful is the Fairy-Tale of Love (Leo Connard, 1918).

Cinema’s vision of the painter’s studio often has the model standing on a pedestal, the painter dressed in immaculate clothing, and the floor covered with oriental rugs.

German postcard by Rotphot in the Film Sterne series, no. 549/2. Photo: Decla. Ressel Orla in Die Sünde/The Sin (Alwin Neuss, 1918).

German postcard by Rotophot in the Film Sterne series, no. 549/4. Photo: Decla. Ressel Orla in Die Sünde/The Sin (Alwin Neuss, 1917).

“In Sin, Ressel Orla has first to play the young thing, who becomes an artist's model under the force of circumstances, in order to save her dying father. When she later stands alone in the world, she rises to happiness without suffering from her past. But then the pride of the woman awakens in her, to whom only the right of her own ego applies.” (Lichtbild-Bühne, 13.07.1918). As often happens in 1910s cinema, the model is ashamed by the artwork based on her own nudity when publicly exhibited, and even awarded.

German postcard by Rotophot in the Film-Sterne series, no. 514/4. Photo: Fern Andra Atelier. Fern Andra and (in the back) Alfred Abel in Ein Blatt im Sturm... doch das Schicksal hat es verweht/A leaf in a storm ... but fate has lost it (Fern Andra, 1917).

In 1910s cinema, the female partners of artists often need to help them out by selling their art, or even their own bodies.

German postcard by Rotophot in the Film Sterne series, no. 516/2. Photo: May Film. Mia May and Bruno Kastner in Ein Lichtstrahl im Dunkel/A Ray of Light in the Dark (Joe May, 1917).

Count Gerd Palm (Kastner) is known for his flattering portraits of his models, so countess Lydia von Grabor (May), who has a hideous nose, asks him to paint her. Gerd sees through her facade and paints her as a lovely mother. He is so enchanted by a song from her that he asks her marry him. Lydia cannot believe him, so he flees. Years pass, the counts has her nose operated, and returns to Gerd, but discovers he has become blind. Dressed as a nurse she takes care of him. Her care makes him retake his work. He hears she is now ready to marry him, but when he still doubts she sings the song she once sang for him and they finally unite.

German postcard by Photochemie, no. K. 2511. Photo: Saturn-Film. Maria Widal in Das sterbende Modell/The dying model (Urban Gad, 1918).

German postcard by Photochemie, no. K. 2510. Photo: Saturn-Film. Maria Widal in Das sterbende Modell/The dying model (Urban Gad, 1918).

Das sterbende Modell seems to have been a variation on Edgar Allen Poe’s 'The Oval Portrait'. The more the model is painted, the more she weakens and eventually dies. Painted portraits may have devastating effects on their models.

German postcard in the Film Sterne series by Rotophot, no. 520/7. Photo: Messter Film, Berlin. Henny Porten and Hermann Thimig in Auf Probe gestellt/Put to the test (Rudolf Biebrach, 1918).

Comedies with artists are rather rare in the 1910s, but a good example is this Henny Porten comedy. As 1910s film convention demands it, the countess prefers the poor, handsome painter to a rich and stupid aristocrat.

Two examples from the French and the Danish cinema

Spanish collectors card by Amattler Marca Luna chocolate, Series 6, no. 2. Photo: Eclipse. Fred Zorilla and Jean Aymé in Lorena (Georges Tréville, 1918)

Lorena (Suzanne Grandais) is the daughter of the marquis of Chambrey (Maillard), and secretly engaged to the painter Pierre Laurent (Fred Zorilla), but her father has other plans. He wants to give her hand to Count Borgo (Jean Aymé), a son of a late friend. As mentioned above, poor but young, handsome, romantic artists were often opposed to old, rich, depraved, and cynic or stupid aristocrats.

German postcard by Photochemie, Berlin, no. K. 1944. Photo: Nordisk Films. Valdemar Psilander in Rytterstatuen (A.W. Sandberg, 1919). The German title is Um das Bild des Königs (For the king's statue).

A young sculptor is commissioned by the Minister to make an equestrian statue of the King, for a high sum of money. He also meets and falls in love with the Minister’s niece. Her father, a banker, is involved in wild speculation, kills himself and leaves a giant debt. Secretly, the artist helps out with his prize money, winning the girl of course. So the artist is not only talented but also a gentleman.

Examples of Italian silent films with Francesca Bertini and Helena Makowska

Spanish postcard by Amatller Marca Luna chocolate, Series 2a, no. 6. Photo: Caesar Film. Gustavo Serena and Francesca Bertini in Il processo Clémenceau (Alfredo De Antoni, 1917). In Spain, the film was released as El proceso Clemenceau.

Il processo Clemenceau (Alfredo De Antoni, 1917) is typical for the parabolas in film plots on artists and their models. Artists discover models, often as young, beautiful and innocent girls. Gradually, the women become depraved thanks to the success of the artists, get hooked on money and luxury, and start to cheat. When the sculptor discovers his lover’s betrayal, he first will smash the plaster bust. In the end he will kill the model too. The artist creates the art work and also the model, but when the model misbehaves and does not correspond anymore with the art work’s purity, he may also destroy both the art work and the model. On the left of the card, a copy of a bust made by Amleto Cataldi, portraying Francesca Bertini, and published in the art journal Emporium in 1917.

Italian postcard by G.B. Falci, Milano, no. 257. Photo: Caesar Film. Francesca Bertini in La donna nuda (Roberto Roberti, 1922), film adaptation of Henry Bataille's classic play La femme nue (1908).

Italian postcard by La Fotominio / Ed. G.B. Falci, Milano, no. 115. Photo: Caesar Film. Francesca Bertini and Angelo Ferrari in the Henry Bataille adaptation La donna nuda (Roberto Roberti, 1922).

Italian postcard by La Fotominio / Ed. G.B. Falci, Milano, no. 264. Photo: Caesar Film. Angelo Ferrari and Francesca Bertini in the Henry Bataille adaptation La donna nuda (Roberto Roberti, 1922).

In La donna nuda (Roberto Roberti, 1920), the painter Pierre Bernier (Angelo Ferrari) becomes acquainted with Lolette (Francesca Bertini), the model of his old friend Rouchard, picked up from the street. Lolette becomes Pierre’s model and his mistress. Pierre becomes famous thanks to his portrait 'The Naked Woman' which represents Lolette. The evening of his triumph at the Salon he decides to marry her, but after having become rich and famous he falls in love with the Princess of Chaban and abandons Lolette, despite owing her his success. After a suicide attempt over her persistently infidel lover, Lolette recovers in the hospital, rejects Pierre, and decides to return to Rouchard. The film was a remake of a film with Lyda Borelli, made in 1914 by Carmine Gallone, while several sound adaptations of Bataille's play would follow.

Italian postcard by IPA CT, no. 3654, V. Uff. Rev. St., Terni. Photo: Ambrosio. Umberto Mozzato as Settala and Mercedes Brignone as his wife Silvia in La Gioconda (Eleuterio Rodolfi 1916, released 1917), based on Gabriele D'Annunzio's play. Caption: 'Lucio Settala in the happy intimacy of the family.'

Italian postcard by IPA CT, no. 3877, V. Uff. Rev. St., Terni. Photo: Ambrosio. Umberto Mozzato as Lucio Settala and Helena Makowska as Gioconda Dianti in La Gioconda (1917).Caption: Sculptor Lucio Settala feels his love for his model Gioconda Dianti is ever expanding.

Italian postcard by IPA CT, no. 3871. Photo: Società Ambrosio, Torino. V. Uff. Rev. St. Terni. Mercedes Brignone in La Gioconda (Eleuterio Rodolfi, 1917). Caption: Sivia Settala deposes flowers in the studio of her husband, constating with great sadness, that he is ever more absent.

Italian postcard. IPA CT, no. 3662. Photo: Società Ambrosio, Torino. Helena Makowska as the model Gioconda Dianti in La Gioconda (Eleuterio Rodolfi, 1917).

Postcards for the lost Ambrosio production La Gioconda (Eleuterio Rodolfi, 1916, released 1917), based on Gabriele D'Annunzio's play, and starring Helena Makowska, Umberto Mozzato, and Mercedes Brignone. The statue for which Gioconda Danti poses does not seem to recall any existing statue, but its style reminds of that of the Italian sculptor Leonardo Bistolfi. As was common in silent films on artists, the actor’s studio is full of plasters referring to Antique and modern sculpture.

An example with a male protagonist

Italian postcard. Photo: Milano Film. Ermete Zacconi in Spettri/Gli spettri (A.G. Caldiera, 1918). Caption: Not being able anymore to paint, to do anything, nothing!

Ermete Zacconi in the Italian silent film Spettri/Gli spettri (A.G. Caldiera, 1918), adapted from Henrik Ibsen's play 'Ghosts' (Gengangere, 1881). Caption: Not being able anymore to paint, to do anything, nothing! Oswald Alving, who has been a painter in Paris, returns home, suffering from depressions. He gets into a state of despair and anguish, when his mother reveals him the woman he loves is his half-sister and he is himself suffering of syphilis, inherited from his father. He asks his mother to help him die by an overdose of morphine in order to end his suffering from his disease, which could put him into a helpless vegetative state.

Two films with Italia Almirante Manzini

Italian postcard by Fotominio, no. 52. Photo: G.B. Falci, Milano. Italia Almirante in La statua di carne (Mario Almirante 1921). Noemi Keller notices the painted portrait of her lookalike Maria, who has died and whom the painter, count Paolo, is still loving, through Noemi.

La statua di carne (Mario Almirante, 1921), starring Italia Almirante Manzini and Lido Manetti. Often in film, deceased persons affect the living ones by their painted portraits. When discovering a painted portrait of the deceased ‘midinette’ Maria, who is her exact lookalike, the mundane stage artist Noemi Keller understands why count Paolo is so obsessed with her. The motif of the Doppelgänger was popular in silent film and in literature. Though based on an original play (1862, by Teobaldo Ciconi, which was already adapted to film in Italy in 1912, the plot of La statua di carne may also remind of the Symbolist novel 'Bruges-la-morte' (1892) by Georges Rodenbach, which inspired various films such as Yevgeni Bauer’s Gryozy/ Daydreams (1915) and Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1959).

Italian postcard by Ed. Ballerini & Fratini, Firenze. Photo: Liliana Ardea and Alberto Collo in L'ombra (Mario Almirante, 1923). Caption: Berta's little friend and the daily painting lesson.

Italian postcard by Ed. Ballerini & Fratini, Firenze, no. 242. Photo: Liliana Ardea and Alberto Collo in L'ombra (Mario Almirante, 1923). Caption: In the new house of Gerardo. Elena: He is your real masterpiece!

Italian postcard by Ed. Ballerini & Fratini, Firenze, no. 248. Photo: Italia Almirante Manzini and Alberto Collo in L'ombra (Mario Almirante, 1923). Caption: Berta: Poor little one! He won't realise to have changed mother. This image represents the final scene of the film.

In L’ombra (Mario Almirante, 1924), Berta (Italia Almirante Manzini) is paralysed. Her husband Gerardo (Alberto Collo), an acclaimed painter, starts a double life with Elena (Liliana Ardea), a former pupil. He even has a child with her. The paralysed woman heals, discovers the fraud, and is devastated, preferring to get paralysed again. In the end, the second woman exits, leaving even her child behind. Mark the unfinished portrait of the child on the right. In the play by Dario Niccodemi, on which the film is based, the interior of the painter’s house is described as being full with portraits of the child.

Sources: Ivo Blom, ‘Of Artists and Models. Italian Silent Cinema between Narrative Convention and Artistic Practice’ (Acta Sapientiae Universitatis. Film and Media Studies 7, 2013, 97-110) and Francesco Geraci, ‘Artisti contemporanei: Amleto Cataldi’ (Emporium, XLV, Vol. 267, March 1917, pp. 163-175).

No comments:

Post a Comment