Italian postcard, no. 303. Photo: A. Badodi, Milano.

Italian postcard, no. 304. Photo: A. Badodi, Milano.

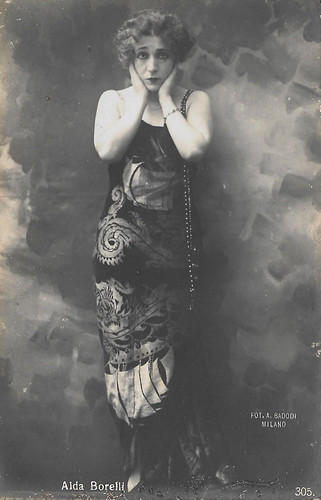

Italian postcard by Ed. A. Traldi, Milano, no. 305. Photo: Badodi, Milano.

Letting her husband shine

Alda Borelli, nicknamed ‘la Alda’, was a true ‘figlia d'arte’, following in the footsteps of her parents’ stage career. She was born in 1879 at Cava de' Tirreni in the province of Salerno where her parents happened to perform then.

Her father Napoleone Borelli, originally a lawyer, belonged to an ancient family from Reggio Emilia. When he was a volunteer with General Giuseppe Garibaldi, he abandoned his profession for the stage. After a stay at the Romanian National Theatre for seven years, he re-emigrated and performed in the company of his son-in-law Alfredo De Sanctis, between 1906 and 1913, the year he died. Alda's mother was the stage actress Cesira Banti.

After having frequented the Scuola normale, Borelli entered the company of Pia Marti Maggi in 1898 and had her debut on stage. In 1901 she entered the company of Alfredo De Sanctis whom she married the same year. Because of the centenary of the death of Italian dramatist and poet Vittorio Alfieri, Borelli had her first big part as Micol in Alfieri’s 'Saul', with Gustavo and Tommaso Salvini.

Just to let her husband shine, Borelli had to play minor parts, and their marriage suffered. Still, she managed to play Flora Brazier in 'Il colonnello Brideau', adapted from 'La Rabouilleuse' (The Black Sheep) by Honoré de Balzac and Bianca in 'I corvi' (Les Corbeaux/The Raven) by Henry Becque.

She also played the Duke of Reichstadt in 'L'aiglon' (The Eaglet) by Edmond Rostand, based on the life of Napoleon's son, Napoleon II of France, Duke of Reichstadt. The role was made famous in France by Sarah Bernhardt.

Italian postcard by Ed. Vettori, Bologna, no. 2.

Italian postcard by Ed. Vettori, Bologna, no. 8.

Italian postcard by Ed. Vettori, Bologna.

Unfit for film

In 1915, Alda Borelli divorced De Sanctis and inscribed herself at the film company Tiber Film in Rome. Here she played in a handful of silent films, including two directed by Emilio Ghione, Tormento gentile/Kind torment (1916) and Il figlio d’amore/L’enfant de l’amour/The child of love (1916).

Already in 1913, she had debuted on the screen in L’eredità di Gabriella/Whom the Gods Destroy, a Savoia production with Maria Jacobini as the title character. This was followed by the Cines production Rinunzia/When Youth Meets Youth (Carmine Gallone, 1914) with Gallone's wife Soava Gallone in the lead.

However, Alda Borelli never became the film diva that her sister Lyda Borelli was in the 1910s. Actually, a critic from Vita Cinematografica considered her acting in Tormento gentile to be 'overacting, unfit for film'. The critic from Apollon praised her acting in Ghione’s other film, the Henry Bataille adaptation L’enfant de l’amour, 'as long as Alda forgets her memories of the stage'.

Alda also tried her luck as a stage wright with the comedy 'Controcorrrente' played by Ugo Piperno in 1918, but it wasn’t a big success. She recognised that her forte was in stage acting, so she returned there in 1918, entering the company of C. Bertramo. Borelli perfectly managed to alternate bourgeois comedy with avant-garde drama.

Striking was her performance as Federica in 'Sorelle d’amore' by Henry Bataille (1919), Anna in La donna di nessuno/Nobody's woman by Cesare Vico Lodovici (1919), and the title character in 'Monna Vanna' by Maurice Maeterlinck (1920). In 1920 Borelli joined the company of Piperno, and performed Mary Chardin in 'Sogno d'amore' (Dream of love) by Giovanni Kossorotoff, a drama with psychological solid contrasts which was a sensation because of the interpretation by Borelli.

Italian postcard by Trevisani, Bologna, no. 64.

Italian postcard by Vettori, Bologna, no. 1057. Photo: Zambini, Parma.

Two years of huge successes

In 1921 Alda Borelli acted a few times together with Tullio Carminati in Alexandre Dumas fils’ 'La dame aux camelias', 'La danza del ventre' (The belly dancer) by Enrico Cavacchioli, and 'Ali' by Sem Benelli. Marco Praga united director Virginio Talli with Ruggero Ruggeri and Alda Borelli as main actors at the Compagnia Nazionale.

This meant two years of huge successes for Borelli. She was the title character in 'Parisina' (1921) by Gabriele D’Annunzio, which successfully led to a stage tour in 1922, and again the lead in 'Nastasia' based on Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s 'The Idiot' (1923). After that she was in 'Come le foglie' by Giuseppe Giacosa (1922), 'Vestire gli ignudi' by Luigi Pirandello (1923), and 'Amara' (1924) by Pier Maria Rosso di San Secondo.

In 1923-1924 she formed her own company with the first actor Marcello Giorda. In 1926 she associated with the German director Rudolf Frank, a pupil of Max Reinhardt to create an avant-garde theatre. Her talent for innovative theatre was confirmed when Borelli played 'L'avventuriera' (L'Aventurière) by Émile Augier. The play was staged in Italy for the first time and created quite a shock.

In 1927 Borelli returned to Beltramo, but already late 1928 she moved to E. Olivieri, her former colleague at the Compagnia Nazionale. The theatre crisis of those years, which continuously caused the breakup of theatre companies, made her decide to leave the stage in 1928. Only 14 years later she returned: in April 1943 she accepted to direct the Gruppo Artistico of the Teatro Odeon in Milan. Her debut there was as Bianca in 'La porta chiusa' (1943) by Praga. She replicated her part of Berta in 'L'ombra' and of Anna de Bernois in 'La nemica', both by Dario Niccodemi, followed by the direction of Addio giovinezza, by Sandro Carnasio and Nino Oxilia, and Amore senza stima by Paolo Ferrari.

In these years her company was the cradle for future famous actors such as Vittorio Gassman. In August 1943 the devastating Allied bombings of Milan caused the company to cease activities. Borelli moved to Rome, where she worked with Tino Carraro and Ernesto Calindri. In July 1952 Alda Borelli performed a last time in Niccodemi’s La nemica at the Teatro Manzoni. Alda Borelli then withdrew from public life. The loss of her son Beno, who killed himself in 1964, aggravated her health. She died in the same year in Milan.

Italian publicity card for Neuroxin. Capture: 'Il Neuroxin è ottimo contro la nevrosia.' Photo: Graziani, Bologna.

Italian postcard by G.B. Falci, Milano, series no. 212. Portrait by C. Monastier. Monastier illustrated many cards in the 1920s, mostly fantasy cards in a sweet romantic style.

Sources: Treccani (Italian), Wikipedia (Italian) and IMDb.

This post was last updated on 9 July 2023.

No comments:

Post a Comment