American actress Colleen Moore (1899-1988) was a star of the silent screen who appeared in about 100 films beginning in 1917. During the 1920s, she put her stamp on American social history, creating in dozens of films the image of the wide-eyed, insouciant flapper with her bobbed hair and short skirts.

French postcard by Cinémagazine-Edition, Paris, no. 212. Photo: First National Pictures.

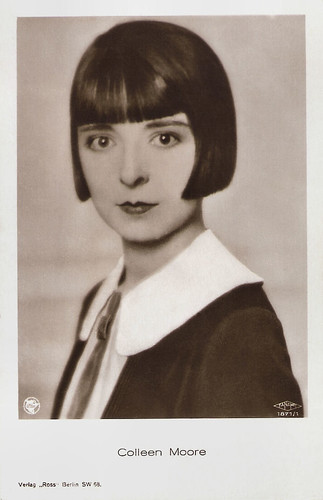

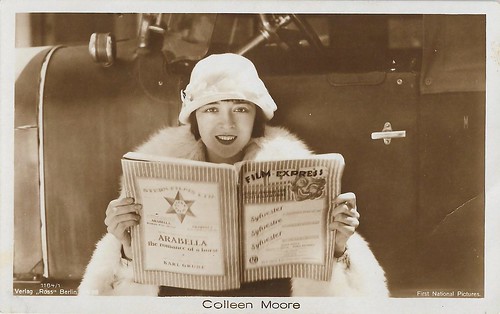

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 3683/3, 1928-1929. Photo: First National Pictures.

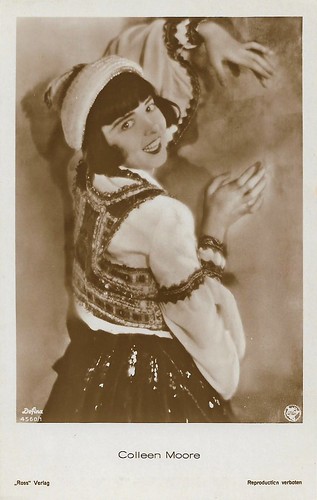

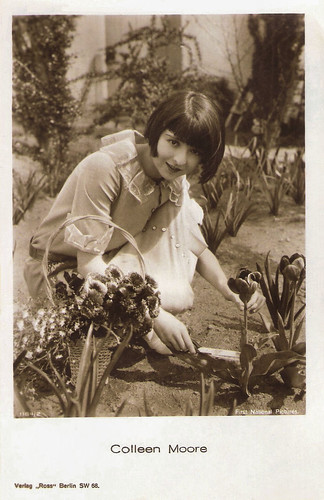

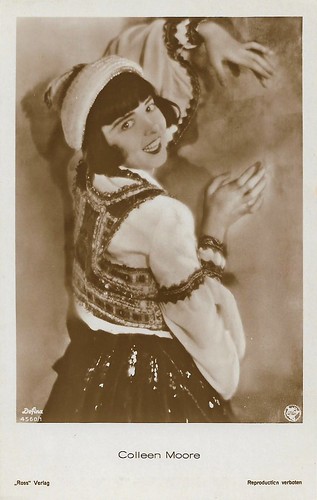

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 3469/2, 1928-1929. Photo: Defina / First National Pictures.

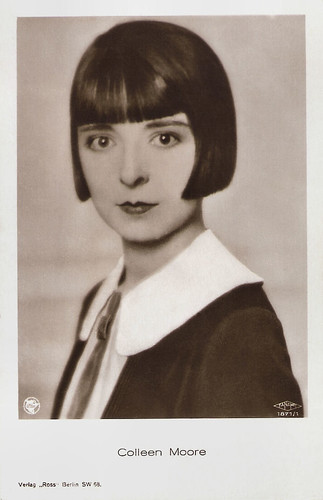

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 3862/1, 1928-1929. Photo: Defina / First-National-Film.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 4943/1, 1929-1930. Photo: First National Pictures / Defina. Publicity still for Synthetic Sin (William A. Seiter, 1929) with Antonio Moreno.

British Real Photograph postcard.

Colleen Moore was born Kathleen Morrison in Port Huron, Michigan, in 1899 (the date which she insisted was correct in her autobiography 'Silent Star' was 1902). Her father was an irrigation engineer, and his job was good enough to provide the family with a middle-class environment.

She was educated in parochial schools and studied piano at the Detroit Conservatory. As a child, she was fascinated with films and stars such as Marguerite Clark and Mary Pickford and kept a scrapbook of those actresses.

By 1917, she was on her way to becoming a star herself. Her uncle, Walter C. Howey, was the editor of the Chicago Tribune and had helped D.W. Griffith make his films The Birth of a Nation (1915) and Intolerance: Love's Struggle Throughout the Ages (1916) more presentable to the censors. Knowing of his niece's acting aspirations, Howey asked Griffith to help her get a start in the film industry.

No sooner had she arrived in Hollywood than she found herself playing in five films that year, The Savage (Rupert Julian, 1917) being her first. Her first starring role was as Annie in Little Orphant Annie (Colin Campbell, 1918).

Colleen was on her way. She also starred in a number of B-films and in Westerns opposite Tom Mix, like The Wilderness Trail (Edward LeSaint, 1919) and The Cyclone (Clifford Smith, 1920).

French postcard by Editions Cinémagazine, no. 178. Photo: Melbourne Spurr.

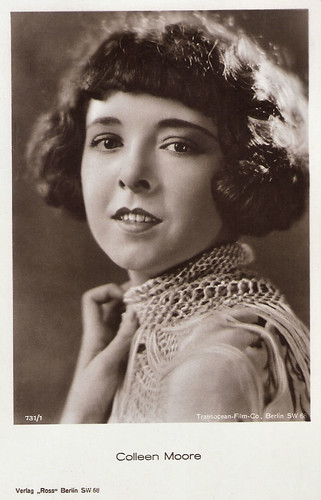

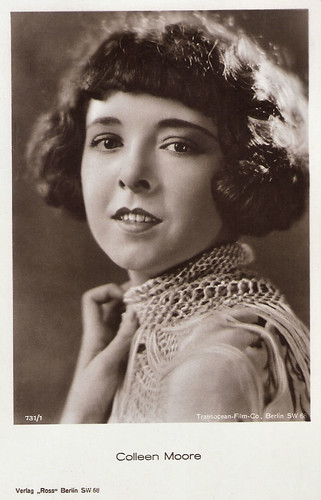

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 731/1, 1925-1926. Photo: Transocean-Film-Co., Berlin.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 731/2, 1925-1926. Photo: Transocean-Film-Co., Berlin.

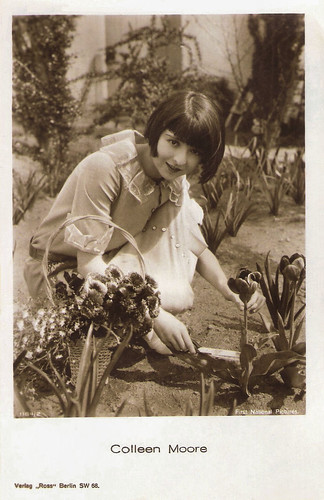

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 896/2, 1925-1926. Photo: First National Pictures, New York.

Austrian postcard by Iris-Verlag, no. 565-1. Photo: First-National-Film. Publicity still for The Desert Flower (Irving Cummings, 1925).

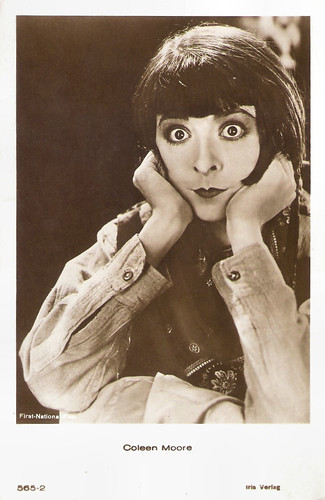

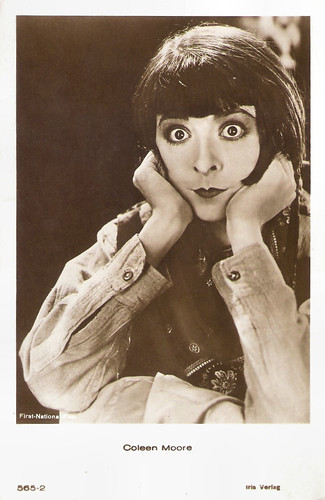

Austrian postcard by Iris-Verlag, no. 565-2. Photo: First-National-Film. Publicity still for The Desert Flower (Irving Cummings, 1925).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 1184/1, 1927-1928. Photo: First National Pictures.

The film, which defined Colleen Moore as the inventor of the 'flapper' look, was Flaming Youth (John Francis Dillon, 1923), in which she played Patricia Fentriss. Her Dutch bob in the film was soon copied by hairdressers across America, and her air of an emancipated young woman inspired countless imitations. In 1923, she married the first of her four husbands, Frank McCormick, production head of First National Pictures, later part of Warner Brothers. There followed such films as The Perfect Flapper (John Francis Dillon, 1924), The Desert Flower (Irving Cummings, 1925), Ella Cinders (Alfred E. Green, 1926) and Her Wild Oat (Marshall Neilan, 1927).

By 1927, she was the top box-office draw in the US, making $12,500 a week. Her second husband was a New York broker, Albert F. Scott. Moore put her money into the stock market, making very shrewd investments. She took a hiatus from acting between 1929 and 1933, just as sound film was introduced. Her four sound pictures released in 1933 and 1934 were not financial successes. Moore then retired permanently from screen acting. Her final film role was as Hester Prynne in The Scarlet Letter (Robert G. Vignola, 1934).

In 1937, she married her third husband, Homer Hargrave, again a stockbroker, and ended her film career. After she retired, she wrote two books on investing, and she travelled widely, frequently to China. At 83, she married her fourth husband, builder Paul Maginot. In 1988, Colleen Moore died of an undisclosed ailment in Paso Robles, California. She was 88. At the time of her death, she was writing a novel, a Hollywood murder mystery centred around a Mae West type.

Tragically, approximately half of Moore's films are now considered lost. Of her most celebrated film, Flaming Youth (1923), only one reel survives. Antti Alanen in his Film Diary: "She herself valued her work, guarded the nitrate reels, and in 1944 deposited them with the Museum of Modern Art Film Department, trusting that they would safeguard them in the way that they had conserved the work of Griffith and Fairbanks. In the 1950s, she went back, only to discover that the First National films had gone. What had happened in between has produced a complex web of evasive myth and individual blame, too late and still too contentious to exhume."

Antti Alanen: "For decades, Why be Good? and Synthetic Sin were thought to be lost films. They were rediscovered through the perseverance of film historian Joseph Yranski and Ron Hutchinson of the Vitaphone Project. The search began many years ago when Joseph interviewed Colleen Moore, who told him that a copy of the film survived in an Italian film archive. Ron Hutchinson was able to find the 16 Vitaphone discs containing the soundtrack of Why Be Good?, and the task of locating the missing picture began. Gian Luca Farinelli of the Cineteca di Bologna contacted Matteo Pavesi of Cineteca Italiana di Milano, who graciously allowed access to the 35mm nitrate dupe negatives for the restoration of both pictures at L’Immagine Ritrovata, Bologna, in conjunction with Warner Bros.”" Why Be Good? had its re-premiere at the Cinema Ritrovato Festival in Bologna in 2014. Synthetic Sin's re-premiere followed in 2015 during the Giornate del Cinema Muto in Pordenone.

Austrian postcard by Iris-Verlag, no. 5855. Photo: First National-Film.

French postcard by Editions Cinémagazine, no. 311.

French postcard by Cinémagazine-Edition, no. 572. Photo: Roman Freulich /First National. The photo was specially posed for Motion Picture magazine in 1928.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 1184/21, 1927-1928. Photo: First National Pictures.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 1871/1, 1927-1928. Photo: First National Pictures / Fanamet.

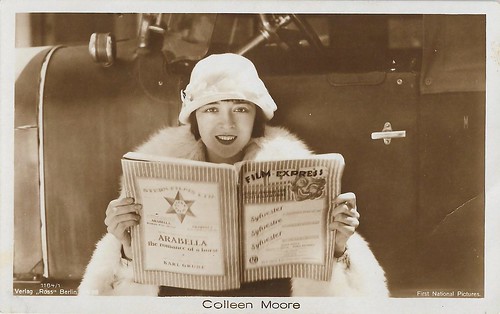

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 3298/1, 1928-1929. Photo: E.O. Hoppé.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 4365/1, 1929-1930. Photo: Defina / First National. Publicity still for Lilac Time (George Fitzmaurice, 1928) with Gary Cooper.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 4366/2, 1929-1930. Photo: Defina / First-National-Film. Publicity still for Oh Kay! (Mervyn LeRoy, 1928).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 4560/1, 1929-1930. Photo: Defina / First National.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 4560/2, 1929-1930. Photo: Defina / First National Pictures.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 5188/1, 1930-1931. Photo: First National / Defina.

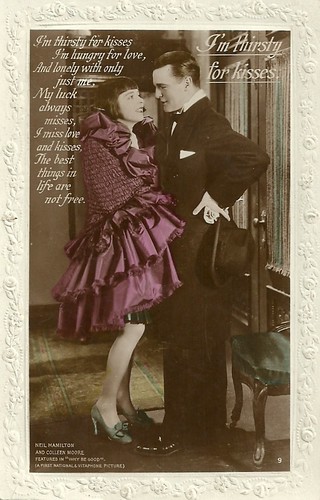

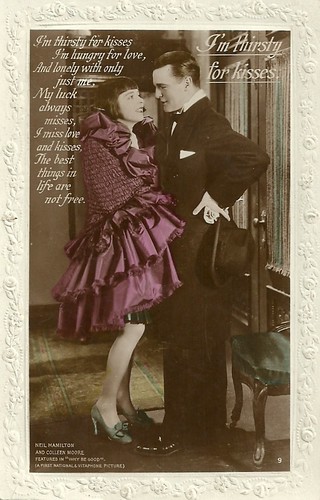

British postcard, no. 9. Photo: First National Pictures. Colleen Moore and Neil Hamilton in Why Be Good? (William A. Seiter, 1929).

Sources: Glenn Fowler (The New York Times), Denny Jackson (IMDb), Antti Alanen (Antti Alanen: Film Diary), Ed Stephan (IMDb), Wikipedia and IMDb.

French postcard by Cinémagazine-Edition, Paris, no. 212. Photo: First National Pictures.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 3683/3, 1928-1929. Photo: First National Pictures.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 3469/2, 1928-1929. Photo: Defina / First National Pictures.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 3862/1, 1928-1929. Photo: Defina / First-National-Film.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 4943/1, 1929-1930. Photo: First National Pictures / Defina. Publicity still for Synthetic Sin (William A. Seiter, 1929) with Antonio Moreno.

British Real Photograph postcard.

Colleen was on her way

Colleen Moore was born Kathleen Morrison in Port Huron, Michigan, in 1899 (the date which she insisted was correct in her autobiography 'Silent Star' was 1902). Her father was an irrigation engineer, and his job was good enough to provide the family with a middle-class environment.

She was educated in parochial schools and studied piano at the Detroit Conservatory. As a child, she was fascinated with films and stars such as Marguerite Clark and Mary Pickford and kept a scrapbook of those actresses.

By 1917, she was on her way to becoming a star herself. Her uncle, Walter C. Howey, was the editor of the Chicago Tribune and had helped D.W. Griffith make his films The Birth of a Nation (1915) and Intolerance: Love's Struggle Throughout the Ages (1916) more presentable to the censors. Knowing of his niece's acting aspirations, Howey asked Griffith to help her get a start in the film industry.

No sooner had she arrived in Hollywood than she found herself playing in five films that year, The Savage (Rupert Julian, 1917) being her first. Her first starring role was as Annie in Little Orphant Annie (Colin Campbell, 1918).

Colleen was on her way. She also starred in a number of B-films and in Westerns opposite Tom Mix, like The Wilderness Trail (Edward LeSaint, 1919) and The Cyclone (Clifford Smith, 1920).

French postcard by Editions Cinémagazine, no. 178. Photo: Melbourne Spurr.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 731/1, 1925-1926. Photo: Transocean-Film-Co., Berlin.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 731/2, 1925-1926. Photo: Transocean-Film-Co., Berlin.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 896/2, 1925-1926. Photo: First National Pictures, New York.

Austrian postcard by Iris-Verlag, no. 565-1. Photo: First-National-Film. Publicity still for The Desert Flower (Irving Cummings, 1925).

Austrian postcard by Iris-Verlag, no. 565-2. Photo: First-National-Film. Publicity still for The Desert Flower (Irving Cummings, 1925).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 1184/1, 1927-1928. Photo: First National Pictures.

The inventor of the 'flapper' look

The film, which defined Colleen Moore as the inventor of the 'flapper' look, was Flaming Youth (John Francis Dillon, 1923), in which she played Patricia Fentriss. Her Dutch bob in the film was soon copied by hairdressers across America, and her air of an emancipated young woman inspired countless imitations. In 1923, she married the first of her four husbands, Frank McCormick, production head of First National Pictures, later part of Warner Brothers. There followed such films as The Perfect Flapper (John Francis Dillon, 1924), The Desert Flower (Irving Cummings, 1925), Ella Cinders (Alfred E. Green, 1926) and Her Wild Oat (Marshall Neilan, 1927).

By 1927, she was the top box-office draw in the US, making $12,500 a week. Her second husband was a New York broker, Albert F. Scott. Moore put her money into the stock market, making very shrewd investments. She took a hiatus from acting between 1929 and 1933, just as sound film was introduced. Her four sound pictures released in 1933 and 1934 were not financial successes. Moore then retired permanently from screen acting. Her final film role was as Hester Prynne in The Scarlet Letter (Robert G. Vignola, 1934).

In 1937, she married her third husband, Homer Hargrave, again a stockbroker, and ended her film career. After she retired, she wrote two books on investing, and she travelled widely, frequently to China. At 83, she married her fourth husband, builder Paul Maginot. In 1988, Colleen Moore died of an undisclosed ailment in Paso Robles, California. She was 88. At the time of her death, she was writing a novel, a Hollywood murder mystery centred around a Mae West type.

Tragically, approximately half of Moore's films are now considered lost. Of her most celebrated film, Flaming Youth (1923), only one reel survives. Antti Alanen in his Film Diary: "She herself valued her work, guarded the nitrate reels, and in 1944 deposited them with the Museum of Modern Art Film Department, trusting that they would safeguard them in the way that they had conserved the work of Griffith and Fairbanks. In the 1950s, she went back, only to discover that the First National films had gone. What had happened in between has produced a complex web of evasive myth and individual blame, too late and still too contentious to exhume."

Antti Alanen: "For decades, Why be Good? and Synthetic Sin were thought to be lost films. They were rediscovered through the perseverance of film historian Joseph Yranski and Ron Hutchinson of the Vitaphone Project. The search began many years ago when Joseph interviewed Colleen Moore, who told him that a copy of the film survived in an Italian film archive. Ron Hutchinson was able to find the 16 Vitaphone discs containing the soundtrack of Why Be Good?, and the task of locating the missing picture began. Gian Luca Farinelli of the Cineteca di Bologna contacted Matteo Pavesi of Cineteca Italiana di Milano, who graciously allowed access to the 35mm nitrate dupe negatives for the restoration of both pictures at L’Immagine Ritrovata, Bologna, in conjunction with Warner Bros.”" Why Be Good? had its re-premiere at the Cinema Ritrovato Festival in Bologna in 2014. Synthetic Sin's re-premiere followed in 2015 during the Giornate del Cinema Muto in Pordenone.

Austrian postcard by Iris-Verlag, no. 5855. Photo: First National-Film.

French postcard by Editions Cinémagazine, no. 311.

French postcard by Cinémagazine-Edition, no. 572. Photo: Roman Freulich /First National. The photo was specially posed for Motion Picture magazine in 1928.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 1184/21, 1927-1928. Photo: First National Pictures.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 1871/1, 1927-1928. Photo: First National Pictures / Fanamet.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 3298/1, 1928-1929. Photo: E.O. Hoppé.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 4365/1, 1929-1930. Photo: Defina / First National. Publicity still for Lilac Time (George Fitzmaurice, 1928) with Gary Cooper.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 4366/2, 1929-1930. Photo: Defina / First-National-Film. Publicity still for Oh Kay! (Mervyn LeRoy, 1928).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 4560/1, 1929-1930. Photo: Defina / First National.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 4560/2, 1929-1930. Photo: Defina / First National Pictures.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 5188/1, 1930-1931. Photo: First National / Defina.

British postcard, no. 9. Photo: First National Pictures. Colleen Moore and Neil Hamilton in Why Be Good? (William A. Seiter, 1929).

Sources: Glenn Fowler (The New York Times), Denny Jackson (IMDb), Antti Alanen (Antti Alanen: Film Diary), Ed Stephan (IMDb), Wikipedia and IMDb.

No comments:

Post a Comment